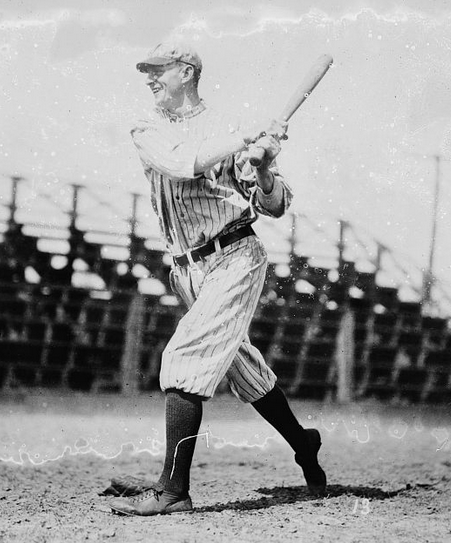

Joe Gedeon

Even the most casual baseball fan is familiar with Eight Men Out, the book (and the movie) that tells the story of the eight members of the Chicago White Sox who were forever banished from organized baseball for fixing the 1919 World Series.

Even the most casual baseball fan is familiar with Eight Men Out, the book (and the movie) that tells the story of the eight members of the Chicago White Sox who were forever banished from organized baseball for fixing the 1919 World Series.

Joe Gedeon was the “ninth man out.” The regular second baseman of the St. Louis Browns, he was permanently barred from organized baseball by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the Commissioner of Major League Baseball, for his minor part in the scandal.

According to most official records Elmer Joseph “Joe” Gedeon was born December 5, 1893, in Sacramento, California, although he apparently tried to shave off a year at the beginning of his career since many early accounts list his year of birth as 1894. The Gedeon clan, including Joe’s parents John and Teresa, emigrated from Hungary and originally settled in the Cleveland area. John and Teresa Gedeon, however, soon joined a portion of the family that decided to seek the American dream on the West Coast. Most settled in the Los Angeles area, but Joe’s parents eventually ended up in Sacramento. Young Joe grew up to become a well-known athlete, starring for Sacramento High School before graduating in 1911.

After high school Joe signed with the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League for $125 per month. His manager was the legendary Kid Mohler, a left-handed throwing second baseman and one of the last players to perform barehanded in the field. Mohler, who appeared in only three major league games in a 25-year playing career, set a record by playing 2,871 professional games at second base. At 40 in 1912, he was still the Seals’ regular second baseman, so the 18-year-old young Gedeon spent most of his rookie year in the outfield. For the season Joe hit a decent .263 and stole 26 bases in 118 games. He played 80 games in the outfield and got into 28 at second base when Mohler was sidelined with an injury. He committed 10 errors at each position.

After the 1912 campaign, Gedeon was taken in the major-minor league draft by the Philadelphia Athletics, but immediately sold to the Washington Senators. The Athletics had finished a game behind second place Washington in 1912 and therefore picked just ahead of the Senators. Philadelphia manager Connie Mack was probably aware of Washington’s interest in the young prospect and drafted Gedeon with the intention of turning him over to Clark Griffith for a quick profit.

In Washington, Gedeon found his progress blocked by Ray Morgan at second base and saw little playing time in 1913. Making most of his appearances in the outfield and at third base, he batted only .183 in 29 games. He did show some pop at the plate, however, blasting three triples. The next year, 1914, he played sparingly before being shipped back to the Pacific Coast League in June to gain some seasoning with Los Angeles. In 39 games with L.A. he batted .274 while splitting time between second base and the outfield before being recalled by the Senators two months later. For the year he played in only four games with Washington.

Joe was disenchanted with the Senators and comfortable in the Pacific Coast League. Since he was getting about the same pay with Los Angeles as he’d been making in the big leagues, he was perfectly content to stay on the West Coast. In the off-season he was managing the Sacramento Acorns in the Sacramento Valley Rookie League when he received orders from Clark Griffith to report to the Senators’ spring training camp in Charlottesville – “a rotten, little mud town down in Virginia,” according to Gedeon. The native Californian had a strong affinity for temperate climates and disliked the big cities back east. One story has it that when Joe was due to arrive for his first major league training camp in Charlottesville, Washington manager Clark Griffith dispatched veteran player/coach Germany Schaefer to meet the youthful recruit at the train station. A midnight snowstorm had blown in, however, and Gedeon, who was seeing snow for the first time, adamantly refused to disembark. “I ain’t getting off in a blizzard for nobody!” he shouted at the shivering Schaefer as the Pullman rolled through the station. He returned a week later when the snow melted. Normally a raw rookie would be unceremoniously booted out of camp for this, but at the time Gedeon was considered such a prodigy that he was forgiven.

Prior to the 1915 season, Gedeon wrote Griffith asking to be allowed to remain with Los Angeles for the year, but he didn’t exactly get his wish. He did get to stay in the Pacific Coast League, but it was with Salt Lake City.

Gedeon enjoyed a spectacular 1915 season with Salt Lake City. For the extended Pacific Coast League season, the 21-year-old phenom played 190 games at second base, banged out 234 hits, scored 133 runs, stole 25 bases, and finished with an excellent .317 batting average. His 67 doubles set a league record, and his fielding percentage was .962, a pretty good mark for the times, especially for first season as a full-time second sacker.

Ray Morgan had endured a sub-par year for the Senators in 1915 and Griffith was counting on Gedeon to push him for the regular second base job the next spring. But Joe had other ideas. He signed a lucrative two-year contract with the Newark entry in the Federal League, which had just completed its second season. Shortly after Gedeon signed, however, the Federal League folded, and the New York Yankees swooped in to purchase his contract for $7,500, a considerable sum for an unproven player in those days. The Senators protested vehemently, but American League President Ban Johnson ruled against them and directed Gedeon to report to New York.

Gedeon was the sensation of the Yankees 1916 spring training camp and starred early in the season, but he faded as the year wore on, a pattern for which he would become notorious. He finished the campaign with a lowly .211 batting average in 122 games at second base. The next year he lost the regular keystone job to Fritz Maisel and appeared in only 33 games.

In January 1918, Gedeon was traded to the St. Louis Browns in a blockbuster deal. The Yankees received star second baseman Del Pratt and veteran southpaw (and future Hall of Famer) Eddie Plank in exchange for Gedeon, Maisel, pitcher Nick Cullop, journeyman catcher Les Nunamaker, and a young righthander named Urban Shocker. The trade worked out well for the Browns, despite the fact that Maisel, Cullop, and Nunamaker were soon gone. Gedeon settled into the Browns’ regular second base job and Shocker eventually became the ace of the pitching staff. Pratt had three solid seasons with the Yankees, but the 42-year-old Plank refused to report to the Yankees and took his 326 lifetime victories into retirement.

For the 1918 season, Gedeon hit only .213 in 123 games, but led American League second basemen in assists, total chances per game, and fielding percentage. He also tied the major league one-game (nine innings) record for assists at second base with 11. In 1919 he improved his batting average to .254 in 120 games and again had the highest fielding average at his position.

After the Browns ended the 1919 season in fifth place, Gedeon decided to stick around and take in the World Series between the Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds before heading back to the West Coast. Gedeon was friends with some of the conspirators on the White Sox, especially Sox shortstop Swede Risberg, who also hailed from Northern California. He had played in the PCL with Risberg, as well as pitcher Lefty Williams and infielder Fred McMullin and had also been a teammate of Chicago first baseman Chick Gandil while both were with the Senators. Unfortunately, Joe seemed to have a knack for getting in with the wrong crowd. He was friendly with certain representatives of the St. Louis gambling community and knew the notorious Hal Chase from California. Gedeon attended the games both in Chicago and Cincinnati and hung out with his buddies on the Sox, even traveling with the team. Not surprisingly he got wind of the fix and put down a few bets.

Rumors of a fix had started circulating even before the 1919 Series began and reached a crescendo when the Sox lost in a suspicious manner. Shortly thereafter, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey offered a $10,000 reward for information regarding the scandal. Gedeon, succumbing to either a troubled conscience or the desire to pocket twenty thousand bucks, traveled to Chicago to meet with Comiskey. He confirmed that games had indeed been fixed and named several prominent St. Louis gamblers who were involved. Predictably, the penurious Comiskey refused to pay Gedeon; dismissing his information as useless. A year later, however, the Cook County Grand Jury would take an entirely different view.

The Cook County Grand Jury was originally convened on September 7, 1920, to investigate the possible fixing of a Chicago Cubs’ game a week earlier. However, the focus quickly shifted to the 1919 World Series and the eight White Sox players. As evidence mounted, the players grew jittery until Cicotte, followed by Jackson and Williams, confessed their involvement and the eight Sox were suspended indefinitely from organized baseball. At the time of the suspension, the Sox stood 1/2 game behind the Cleveland Indians with three games left in the season against Gedeon’s St. Louis Browns.

During those last weeks of the 1920 season, while the controversial hearings raged, Gedeon was a nervous wreck. According to a November 4, 1920, Sporting News article he “trembled in constant fear and dread, lost 20 pounds, and played ball like a man dumb and dazed.” His batting average dropped from .300 to .292 in the final days of the season. The added pressure of playing the last three games against the Sox, with the conspicuous absence of the suspended players, undoubtedly took a tremendous toll.

Shortly after the season ended with the Sox in second place, Gedeon’s name surfaced in the continuing investigation and he voluntarily journeyed from his California home to appear before the Grand Jury. According to his testimony, he and the infamous Chase (who managed to dodge the proceedings) bet on the Reds on a tip from one of the indicted players – presumably Risberg. On the witness stand Gedeon also revealed the existence of the group of St. Louis gamblers involved in the fix. In fact, he may have inadvertently been responsible for their involvement. After receiving the tip, Joe had asked some friendly St. Louis “sporting men” for assistance in getting some money down on the Reds, thereby alerting the local gambling community that something was up.

Shortly after the season ended with the Sox in second place, Gedeon’s name surfaced in the continuing investigation and he voluntarily journeyed from his California home to appear before the Grand Jury. According to his testimony, he and the infamous Chase (who managed to dodge the proceedings) bet on the Reds on a tip from one of the indicted players – presumably Risberg. On the witness stand Gedeon also revealed the existence of the group of St. Louis gamblers involved in the fix. In fact, he may have inadvertently been responsible for their involvement. After receiving the tip, Joe had asked some friendly St. Louis “sporting men” for assistance in getting some money down on the Reds, thereby alerting the local gambling community that something was up.

On the stand, Gedeon claimed to have pocketed between $600 and $700 from his bets. When asked to explain his relatively paltry winnings, he said his conscience started to bother him after his initial enthusiasm to make a killing had passed. But his belated addition that he also didn’t have much seed money may have been a greater factor. After his appearance before the Grand Jury, it was announced that Gedeon was exonerated from complicity in the throwing of games in the Series, but had materially strengthened the case against some of the men already indicted.

Outside the courtroom, Gedeon told reporters that he feared he was through with baseball. And he was right. The Browns had summarily dropped him from their roster a year earlier, immediately after his grand jury appearance. On November 3, 1921, according to a brief notation in the 1922 Reach Guide, Commissioner Landis officially and permanently disqualified Joe Gedeon for having guilty knowledge of the conspiracy.

The Browns had finished in fourth place in 1920, with young superstar George Sisler hitting .400 at first base; Kenny Williams, Baby Doll Jacobson, and Jack Tobin all topping .300 in the outfield; and Gedeon teaming with shortstop Wally Gerber to form a classy double play combination. The next season, without Gedeon, they finished third. Seven players tried their hand at second with rookie Marty McManus, a converted third baseman, finally settling in as the regular. In summarizing the 1921 season the Reach Guide noted the Browns’ season-long infield weakness due to the release of Joe Gedeon.

In 1922 the powerful New York Yankees, led by Babe Ruth, captured their second straight pennant in the initial stages of their incredible dynasty. The Browns fought them down to the wire, however, and when the dust settled a single game separated the two clubs. McManus was solid with the bat, but led the league in errors at second base while a host of prospects and suspects mishandled the hot corner. It’s probable that with Gedeon at second and McManus at his natural third base post, the Browns would have made up that game on the Yankees and captured the American League pennant. Instead, the cross-town Cardinals captured the first St. Louis pennant of the 20th century when they won the National League flag in 1926. They also captured the City’s heart; and after a few more Cardinals triumphs the Browns were relegated to permanent also-ran status until they fled to Baltimore in 1954.

The redheaded Gedeon was a rangy, 6-foot, 167-pound, right-handed hitter with good speed and an excellent glove. At the time of his suspension, he was only 26 years old and just reaching his prime. From 1918, his first season with the Browns, to 1919 he raised his average more than 40 points. In 1920 he bumped it up another 38 points to a solid .292. After leading the league at his position the previous two years his fielding average tailed off somewhat in 1920, but he established himself as an offensive force in the number two spot in the order. He scored 95 runs in 153 games and successfully sacrificed 48 times to tie Donie Bush for the league lead, as well as the seventh highest single season total in major league history. In noted reporter F.C. Lane’s book Batting, Gedeon is referred to as one of the best hit-and-run men in the game.

Joe appeared to be well liked by teammates and management. St. Louis Browns General Manager Bob Quinn was reportedly shocked by reports that Gedeon was involved in the Series fix and refused to believe them until he heard Joe’s testimony. Gedeon also seems to have had a well-developed sense of humor. An often-told story involves an encounter between fireballer Walter Johnson and Gedeon, when he was with the Yankees. After a called strike by umpire Billy Evans, Gedeon asked where the pitch was. Sensing a dispute, the suspicious arbitrator asked why he wanted to know. “I never saw it. I had my eyes closed,” Joe admitted sheepishly.

It can be argued that Gedeon was treated unfairly. After all, he didn’t play in the Series, and there’s no proof that he had anything to do with plotting the affair. In fact, Joe insisted that he didn’t even know about the fix before the Series started. Gedeon’s “guilty knowledge” doesn’t appear to be any greater than that of several other players on the fringe of the scandal, including some of the “clean Sox.” What set Gedeon apart was that he willingly cooperated with the Grand Jury and apparently volunteered the truth.

Apparently unconvinced, The Sporting News bade farewell to Gedeon: “There are other Joe Gedeons – ballplayers who are as culpable as the former second baseman of the Browns, but they are not bowed in shame. . . . When we look at them or recall their names as they have appeared on the suspected list, we can but think: Gedeon, bad as you appear, you are a credit to baseball beside those you have left behind.”

Gedeon was probably a victim of baseball politics, specifically the on-going battle between Comiskey and American League President Ban Johnson. After Comiskey suspended the eight White Sox players, he kept them on the club’s reserve list for the 1921 season. However, Browns’ owner Phil Ball, a loyal Johnson supporter, unconditionally released Gedeon despite the fact that he had been exonerated by the Grand Jury. Commissioner Landis’ ban also appears to be something of an afterthought. Landis permanently suspended the eight Black Sox from organized baseball immediately after their acquittal in an August 1921 trial, but Gedeon wasn’t “officially” banned until almost three months later.

The November 3, 1921, edition of The Sporting News contained an article dated November 1 regarding a request to Landis from the president of the Pacific Coast League for a clarification of Gedeon’s status. It seems that Joe was slated to play for a California League team in a November 11 exhibition game in Marysville against a team that included several major leaguers. The article termed the request a “joke,” considering it unnecessary since Gedeon had already been playing against “players in good standing in organized baseball” including at least five Pacific Coast League players and one major leaguer.

The article went on to say that Gedeon was eager for a decision. He felt that he shouldn’t be banned when other players who had as much knowledge of the fix as he did “were still playing in the major leagues and even, it is hinted, taking part in the 1921 World Series.”

Unlike some of his cases while on the federal bench, Landis rendered his decision on Gedeon with amazing speed, but it wasn’t the one the ballplayer was eager for.

Despite some initial speculation about an appeal, Gedeon quickly dropped out of sight after his formal banishment-as far as baseball was concerned. He resurfaced briefly when he was arrested in Sacramento on October 7, 1924, for violating the 18th Amendment (Prohibition). In 1933, Joe was in trouble with the law again when he was nabbed in Seattle with $400 in counterfeit $10 bills. He first gave his name as Joe Davis, before admitting his true identity.

Otherwise, he lived in obscurity, eventually settling in Galt, a small town near Sacramento until moving to San Francisco in the late 1930s.

Gedeon preceded all of the banished Sox to the grave. He suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and died from bronchial pneumonia on May 19, 1941, after more than two months in a San Francisco Hospital. He was only 47 years old. He was buried in Sacramento’s East Lawn Cemetery where several of his high school teammates served as pallbearers.

On his death certificate his occupation was listed as retired saloonkeeper. The document indicated that he was married to Florence Gedeon at the time of his death, but his Sacramento obituary stated only that he was survived by a son, William, and a sister, Marie. Brief obituaries in the New York Times and the San Francisco Examiner referred to him as an ex-ballplayer, but failed to mention his role in the scandal which cost him his career.

In Joe’s obituary, the Sacramento Bee provided a somewhat biased synopsis of his brief career: “Joe was never a batter of high average but he offset that by being a mighty smart batsman. Most of the time in his major league career he was second in the hitting order and was regarded as one of the best in the tricky business of the hit and run. Gedeon was a wonderful defensive player. His fielding at second base brought him the rating as one of the greatest keystone artists in the majors.”

Despite Landis’ banishment, the Gedeon name would resurface on a major league roster almost twenty years later when Joe’s nephew and namesake Elmer John Gedeon appeared in five games for the Washington Senators (Joe’s original team) in 1939. Like his uncle, Elmer’s career ended prematurely under unfortunate circumstances. He was inducted into the United States Airforce before the 1941 season and became one of only two major leaguers to die in combat when his plane was shot down over France in 1944.

Sources

Eight Men Out by Eliot Asinof, c1963 Henry Holt & Company

Elmer Gedeon by Gary Bedingfield @ BaseballLibrary.com

Bloom of the Morning Glory Average by Clifford Bloodgood, article in Baseball Magazine (1935)

Shoeless Joe and Ragtime Baseball by Harvey Frommer, c1992 Taylor Publishing Company

Say It Ain’t So, Joe! The True Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson by Donald Gropman, c1992 Carol Publishing Group

Batting by F.C. Lane, c2001 SABR Publishing

Baseball Anecdotes by Daniel Okrent and Steve Wulf, c1989 Oxford University Press

The Ninth Man Out by Rick Swaine, book section from The National Pastime, c2000 SABR Publishing

Various articles and clips from Gedeon’s Hall of Fame file including:

New York Times

Chicago Tribune

St. Louis Post Dispatch

Sacramento Bee

San Francisco Examiner

Various articles and references in The Sporting News

California Death Certificate

Full Name

Elmer Joseph Gedeon

Born

December 5, 1893 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

Died

May 19, 1941 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.