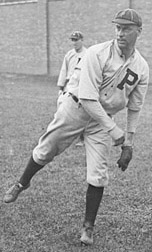

Joe Oeschger

Pitcher Joe Oeschger (pronounced “Eshker”) compiled an 82-116 won-lost record in a dozen major-league seasons from 1914 to 1925, mostly with second-division National League teams. The right-hander’s durability was unquestioned; he completed 99 of 199 starts, and is the only hurler in big-league annals to pitch two games of 20-plus innings.

Pitcher Joe Oeschger (pronounced “Eshker”) compiled an 82-116 won-lost record in a dozen major-league seasons from 1914 to 1925, mostly with second-division National League teams. The right-hander’s durability was unquestioned; he completed 99 of 199 starts, and is the only hurler in big-league annals to pitch two games of 20-plus innings.

On May 1, 1920, Oeschger, of the Boston Braves, and Leon Cadore, of the visiting Brooklyn Robins, both pitched all 26 innings in what is still the longest game in major-league history. The contest, played in inclement weather, commenced at 3 in the afternoon and was halted by darkness after 3 hours and 50 minutes with the score tied at 1-1. Boston tallied its run in the fifth inning to match Brooklyn’s marker in the fourth. Cadore surrendered 15 hits and Oeschger nine over the 26 frames, and over the final nine innings, Joe pitched no-hit ball. Oeschger’s 21 consecutive scoreless innings in one game is another big-league record.

A year earlier, at Philadelphia on April 30, 1919, working for the Phillies, Oeschger was involved in another marathon with the Robins. He and Brooklyn spitballer Burleigh Grimes went the full 20-inning route in a wild 9-9, no-decision fracas. The score was tied 6-6 after nine innings, and the two hurlers threw goose eggs until the 19th frame, when each club scored three runs. Umpires stopped the game on account of darkness after the 20th inning.

Pitching wasn’t the only facet of Joe’s life with enduring quality; after retiring from baseball, he spent 28 years as a teacher and administrator in the San Francisco public school system, and later in life he continued to be actively involved with fishing, hunting, and travel until death came at the age of 94.

Joseph Carl Oeschger was born on May 24, 1892, in Chicago. His parents, Joseph Benedict and Maria M. Oeschger, were Swiss immigrants, and according to Harold Esker of Ohio, the family tree dates back to Jacob Oeschger in 1617. Shortly after Joe’s birth his family moved from Chicago to Boulder Creek in Santa Cruz County, California, and in 1900 settled in Ferndale, 100 miles south of the Oregon-California border. His father bought 100 acres there and operated a dairy farm on for many years.

Joe grew up with five younger siblings: brothers Walter, George, and Vernon, and sisters Ida and Clara. The boys took part in athletics at Ferndale High School, and also played on baseball teams in the towns and lumber camps in the area. After high school Joe was accepted at St. Mary’s College in Oakland, where he studied engineering, played football, and became a star hurler on the baseball team, nicknamed the Phoenix.

St. Mary’s alumnus Eddie Burns, a catcher, had reached the major leagues with the Phillies in 1913, and when Oeschger graduated, encouraged his friend to sign with that club. He did, and made his major-league debut on April 21, 1914, starting and losing to the Boston Braves, 4-3. Labeled California Joe by the Philadelphia press corps, the 22-year-old rookie was brought along slowly by manager Red Dooin, and didn’t win as a starter until June 2, when he beat the New York Giants, 9-2. On the season, he posted a 4-8 record with a 3.77 ERA, pitched 124 innings over 32 games, and made 12 starts. The Phils finished in sixth place, 20½ lengths behind Boston’s Miracle Braves.

Hopes were high in the Philadelphia training camp in the spring of 1915; the previous year Grover Alexander had won 27 games and Erskine Mayer 21, and much was expected of Oeschger, as the pseudonymous Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Jim Nasium wrote: “The thing he has heretofore lacked to place him side by side with the great Alexander has been control and confidence.” Early in the season, though, new Phillies skipper Pat Moran shipped California Joe to Providence in the International League. He worked 252 innings for the Grays, totaled more strikeouts (127) than walks (91), and with a 2.50 earned-run average, won 21 games and dropped 10. His most impressive outing was a no-hit, 1-0 victory over the Toronto Maple Leafs on July 14. The only blemish to a perfect game was a base on balls issued to a Toronto batter in the final frame.

Oeschger was recalled in September and became witness to the Phillies’ successful run to the pennant. Moran’s squad completed the season with a seven-game bulge over the Braves, and with the flag clinched Joe started the second game of the season-ending twin bill with Brooklyn. He pitched a complete-game, 3-2 win, and despite hurling only 23 innings in six games, was included in the World Series payout. The Boston Red Sox defeated Philadelphia four games to one, and Joe pocketed a check for $830.74, one-third of the loser’s full share.

St. Mary’s College was well represented in the 1915 World Series: Former Phoenix players Duffy Lewis, Harry Hooper, and Dutch Leonard played prominent roles for the Red Sox; Burns caught for the Phillies, and Oeschger occupied the bench and didn’t get into the Series. Afterward, Joe returned to Oakland, California, where he married Ivy May Teal in November. The couple had two daughters and a son (Gertrude, Phyllis, and Joseph).

The Phillies were primed to defend the National League title on the strength of the ’15 win totals of its pitchers: Alexander, 31; Mayer, 21; Al Demaree, 14; and Eppa Rixey, 11. In absentia, for the most part, was Oeschger. He took a liner off his glove hand in spring training, suffered a laceration, and was placed on the disabled list. He never got untracked, and finished the season with a 1-0 record, working only 30 1/3 innings in 14 games. The club posted a better winning percentage than the previous year, but finished in second place, 2½ games behind Brooklyn.

Oeschger bounced back in 1917, hurling 262 innings with a 15-14 won-lost mark and a 2.75 ERA. One of his best outings was a no-decision game on June 11, when he matched zeroes with Brooklyn pitcher Jeff Pfeffer in a 14-inning scoreless tie. The Phillies finished second again, 10 games in back of New York, and Alexander hit the 30-win plateau for the third straight season.

The 1918 season was shortened by three weeks with a raft of players off to fight the war in Europe. The Phillies skidded to sixth place, had the highest ERA in the league (3.15), and tied for the NL’s lowest batting average (.244). Oeschger posted an ERA of 3.03, with a won-lost record of 6-18; five of the losses were one-run games, and two others were scores of 2-0.

The 1919 season was pivotal in the career of the 27-year-old Californian; he was traded twice, and ended the year with four victories and four defeats. After one loss and three no-decisions (including the 9-9, 20-inning game with Brooklyn), he was dealt to the NewYork Giants on May 27 for infielder Ed Sicking and pitcher George Smith.The day after the trade Giants manager John McGraw used Oeschger to begin the 10th inning in a 2-2 tie with Pittsburgh. He was removed after walking the first two batters, and charged with the 6-2 loss. He started against Brooklyn on May 31, and was lifted after giving up four hits and no runs in the first inning. He made only three other appearances, and on August 1, the Giants made a deal with the Braves, sending catcher Mickey O’Neil and hurlers Red Causey, Johnny Jones, and Oeschger, along with $55,000 in cash, to the Braves in exchange for pitcher Art Nehf. New York won four pennants during Nehf’s seven seasons there.

Oeschger picked up his first victory as a Brave on August 26, shutting out the Chicago Cubs, 1-0. He notched three other wins to finish the Boston portion of the year with a 4-2 record. His roommate with the Braves in 1919 was the legendary Jim Thorpe, who experienced the best of his six big-league seasons that year, batting .327 in 62 games. When asked about the Olympics hero, Oeschger said, “He was a tremendous athlete; he looked terrible at times on curveballs, but would beat out a lot of infield hits.”

Oeschger’s first and last starts of the 1920 season were 1-0 wins; on April 15, in the second game of the campaign, he blanked the Giants, and on September 29, the Phillies. He pitched three other shutout victories, by scores of 1-0, 1-0, and 2-0, and overall won 15 games and lost 13. Of 30 starts, he completed 20, and worked 299 innings. On April 20 at Brooklyn he lost a tough 1-0, 11-inning game to his nemesis, Cadore; the two would meet again 11 days later and pitch 26 innings!

Boston’s stock rose in 1921; the club climbed to fourth place (79-74), 15 games behind the champion Giants. Oeschger was a 20-game winner for the only time as a major leaguer, and his pitching log included 14 losses, 299 innings pitched, 19 complete games, a 3.52 ERA, and a league-leading 97 walks and 15 hit batsmen. With the bat, he hit .255 (28-for-110), with 11 RBIs, his best season at the plate.

Joe drew the Opening Day assignment that season, opposing Brooklyn and Cadore again. He was beaten, 5-4, when the Robins scored three runs in the eighth and two in the ninth. His 20th victory, a 6-3, complete-game verdict over the Giants on September 4, was decided when Billy Southworth’s three-run homer off Art Nehf broke a 3-3 deadlock.

Boston lost 100 games the next two years, finishing in the cellar in ’22 and seventh in ’23. Oeschger’s statistics paralleled those of the club; a 6-21 won-lost mark in ’22 and 5-15 the next campaign, when his ERA skyrocketed to 5.68. In November 1923 the Braves and Giants negotiated a trade: Southworth and Oeschger to New York in exchange for Dave Bancroft, Bill Cunningham, and Casey Stengel. It was a unique deal, as three of the players later became major-league pilots. Bancroft was immediately named player-manager of the Braves, and years later, Southworth and Stengel earned Hall of Fame plaques as managers of pennant-winning teams.

Oeschger saw little duty with the Giants in 1924, hurling only 29 innings in 10 games, but picked up two wins without a loss. The Giants won the National League pennant by 1½ games over Brooklyn; arguably, Joe’s pair of wins provided New York with its margin of victory. He wasn’t around for the celebration, however, having been released on waivers in June and claimed by the Phillies on July 1.

With the end of the line in sight, Oeschger made 10 starts with Philadelphia in ’24, won two games and dropped seven. He returned to the Phillies the following spring, was placed on the waiver wire, and was picked up by Brooklyn on April 20, 1925. He saw limited duty under Wilbert Robinson; hurling 37 innings in 21 games, he made three starts and had a one-win, two-lost record. He was unconditionally released on September 9, and the Show was over for the veteran right-hander.

In 1926 Oeschger was 34 years old, and took a whirl in the Pacific Coast League, splitting the season between Mission and Oakland. His combined five wins and 14 losses didn’t benefit either of the first-division clubs. Released by Oakland in January 1927, he signed with Mobile in the Southern Association, where he pitched in eight games and was charged with one loss. The end had come.

After baseball, the engineering graduate of St. Mary’s College embarked on a second career; he hit the books at Stanford University and earned a degree in education.

He took his teaching credential to Portola Junior High School in San Francisco, where he taught physical education and hygiene. He retired as vice principal, and said of the teaching experience: “I was there for 28 years and loved every minute of it. The students were wonderful to teachers then.”

After retiring from Portola, Oeschger and his second wife, Nancy Sullivan, moved to the family property in Ferndale. The two enjoyed traveling to Mexico, and Joe stayed in shape with ranch chores, hunting, and fishing trips. The old hurler also responded to mail from baseball fans who inquired about the 26-inning classic; he sent each one an autographed picture and copy of the game’s box score.

On May 23, 1964, Oeschger was listening on the radio to the Giants-Mets game in New York. San Francisco emerged the victor, 8-6, after playing 23 innings, and he was asked to compare the game with the historic 1920 marathon. He pointed out that both teams used six pitchers, a total of 41 players took part, and it took 7 hours and 23 minutes to finish the contest. In contrast, the 26-inning classic hurled by Oeschger and Cadore in 1920 employed just 22 players, and was played in 3 hours and 50 minutes.

On May 1, 1977, 57 years after the historic game, the Native Sons of the Golden West dedicated Joseph C. Oeschger Field in Ferndale. A plaque commemorating the occasion was installed, a beef barbecue luncheon was held, and the Ferndale High School band played the Star Spangled Banner and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” before a Little League game. Four weeks later, on May 29 in San Francisco, Joe was the guest of honor at Candlestick Park, and threw out the first pitch before the Braves-Giants game. San Francisco won, 3-2, in 10 innings!

The Phillies held a season-long celebration in 1983 in observance of the 100th anniversary of the team’s entry into the National League. As the only surviving member of the 1915 pennant-winner, Oeschger was invited to throw out the first pitch at one of the World Series games in Philadelphia. It was his last appearance in the limelight.

The durable pitcher/educator died of a heart attack on July 28, 1986, in Rohnert Park, California. Joseph Carl Oeschger was 94 years old, and the last survivor of the famed 26-inning game. He was buried at Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in Colma, a few miles south of San Francisco.

April 24, 2011

Sources

In preparing this biography, the writer used clippings from the Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Also helpful were Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball; Retrosheet; Baseball-Reference.com; la84foundation.org; genealogybank.com; SABR member Ray Nemec; and special thanks to friend Chuck Moran, who discovered the plaque in Ferndale, and Harold Esker of Akron, Ohio, who contributed Oeschger family genealogy.

Full Name

Joseph Carl Oeschger

Born

May 24, 1892 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

July 28, 1986 at Rohnert Park, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.