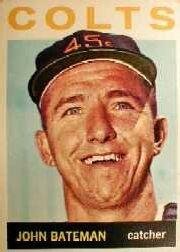

John Bateman

In 1970 sportswriter Ted Blackman quipped, “If John Bateman bought a pumpkin farm, they’d cancel Halloween.”[fn]“Hustling Bateman Frets in Hospital Bed,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970, 24.[/fn] The luckless reference was to the cursed timing of a kidney injury that hospitalized the Montreal Expos starting catcher two days before the start of the 1970 season, yet also serves to describe Bateman’s often ill-fated life. Initially, his 11-year professional career appeared charmed when, in response to a 1962 letter-writing campaign to various major-league clubs, Bateman found himself the starting catcher for the Houston Colt .45s a year later. Injury and inexperience — one year in Class C before his major-league debut — foiled a budding career and limited Bateman to less than 3,600 plate appearances. But baseball proved a fortunate pursuit for John Alvin Bateman for without it, this hard-living youngster’s life might have played out far worse.

In 1970 sportswriter Ted Blackman quipped, “If John Bateman bought a pumpkin farm, they’d cancel Halloween.”[fn]“Hustling Bateman Frets in Hospital Bed,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970, 24.[/fn] The luckless reference was to the cursed timing of a kidney injury that hospitalized the Montreal Expos starting catcher two days before the start of the 1970 season, yet also serves to describe Bateman’s often ill-fated life. Initially, his 11-year professional career appeared charmed when, in response to a 1962 letter-writing campaign to various major-league clubs, Bateman found himself the starting catcher for the Houston Colt .45s a year later. Injury and inexperience — one year in Class C before his major-league debut — foiled a budding career and limited Bateman to less than 3,600 plate appearances. But baseball proved a fortunate pursuit for John Alvin Bateman for without it, this hard-living youngster’s life might have played out far worse.

John was born July 21, 1940, in Fort Sill, an Army post in Lawton, Oklahoma. The Bateman family traces its roots to the Midwest in the early 19th century. During the Civil War John’s great-grandfather Thomas served in the Union army from Logan County, Illinois. In the 1890s Thomas’ son Alvin trekked south during the Oklahoma land rush. Staking land in former Indian Territory the farmer and his wife Euphema Alberta “Bertie” (nee Sandusky) raised four children. The youngest child — by a wide margin — was Thompson J.W. (“TJ”) Bateman. TJ chose a career in the Army after marrying fellow Oklahoman Mildred Roberts, the second daughter born to a laborer employed by the Works Progress Administration during the Depression. Regrettably, TJ and Mildred proved to be less than ideal parents. John and his younger brother Tommy were raised by Mildred’s older sister Jewel and her husband, Raymond Priest.

Sports were one of John’s few safe havens throughout a troubled childhood. Yet exempting a phenomenal right throwing arm John did not stand out athletically. He played American Legion ball for the Lawton Colonels, basketball and baseball for the Lawton High Wolverines but his efforts attracted little attention, especially from major-league scouts. This all changed when John went through a considerable growth spurt — to 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds — after graduation. His baseball prowess grew commensurate with his growing body.

However, John’s early adult years included many less-productive pursuits. A childhood friend recalls stories of a marriage that lasted mere weeks while John struggled with barroom brawls and other antics that kept him under the watchful eye of law enforcement. Around 1959-60, John’s aunt finally tired of her difficult nephew and sent him to live with his father, a master sergeant who had been transferred to Fort Hood in Killeen, Texas. In this central-Texas region TJ appears to have secured a place for his son on the fort’s baseball teams where John’s skills continued to flourish.

Anxious to see where his late-developing talent might take him, John began writing to various major-league clubs requesting a tryout. In March 1962 the newly formed Houston Colt .45s invested $50 — the cost of a sweatshirt, a new mitt and a bus ticket for Bateman to travel to Texas City, site of their amateur camp southeast of Houston — to look at the right-handed hitter. Scout Red Murff, who conducted the camp, took an instant liking to Bateman and urged his signing. Murff did so in part because he believed the 21-year-old to be two years younger.[fn]It appears Bateman also presented himself as a native-Texan to appeal to the only Texas-based major-league team.[/fn] Bateman was not the first player to lie about his age in order to appear more attractive to major-league scouts. But he is one of the few whose lie was never eventually disclosed. Every team roster published throughout Bateman’s playing career incorrectly listed his birth in 1942.

Bateman was assigned to the Modesto Colts — Houston’s Class C affiliate in the California League — where he made an immediate impression. A 19-game hitting streak in the summer contributed to a .280 average, while his 21 home runs and 75 RBIs placed among the team leaders. Nor did his defense disappoint. Houston’s general manager, Paul Richards, exclaimed, “[Bateman is] the new Gabby Hartnett [a Hall of Famer] at throwing the ball. He can just grab the ball and fire it.”[fn]“Colts Grooming Sparkling Crew of Kid Catchers,” The Sporting News, November 17, 1962, 28.[/fn] Bateman was subsequently assigned to the Arizona Instructional League where, while competing for the batting title, he ballooned to 245 pounds. He sustained a hairline fracture on the finger of his throwing hand and the franchise — not wanting to gamble with their newly found prize — sent him home after 31 games.

Described as “agile, aggressive, has desire — and a good swing,”[fn]“Tribe Rookie Given Nod in Cactus Loop,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1963, 6.[/fn] in the spring Bateman turned some heads when he brashly announced he would make the Houston roster in 1963. Three weeks before the start of the season Colts manager Harry Craft concurred: “John Bateman is our No. 1 catcher at this stage and the others will have to beat him out of the job.”[fn]“Bateman Grabs Lead in Race for Colts’ No. 1 Catching Job,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1963, 26.[/fn] But the team’s “hottest young prospect”[fn]“N.L. Writers Make Their Picks,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 14.[/fn] missed Opening Day after sustaining a thumb injury. Bateman made his major-league debut April 19, 1963, in a difficult manner: as an eighth-inning pinch-hitter against one of baseball’s most dominant pitchers ever, Sandy Koufax. Bateman struck out. He had more success over the next two days when, as Houston’s starting catcher, he collected his first major-league hit off Johnny Podres on April 20. His first home run came the next day.

Twenty-six days later Bateman admitted to some nervousness when, with 24 major-league games under his belt, he was behind the plate during Don Nottebart’s no-hitter — the franchise’s first. Despite Bateman’s league-leading passed balls and errors committed as catcher — due in part to Houston’s two knuckleball-throwing starters — pitchers found him a reliable backstop. The St. Louis Cardinals dubbed Bateman the “best throwing catcher in the league.”[fn]“Bateman, Spangler Make Sharp Report in .45’s Popgun Attack,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963, 11.[/fn] But his contributions were not limited to defense. Despite a meager .210 average Bateman led the team in RBIs (59 – fourth among catchers in the majors), triples (6) and homers (10, including a surprising inside-the-park home run for the lead-footed catcher). Bateman established a major-league record with the fewest walks (13) in a 100-strikeout season but this dubious distinction did not detract from the consideration he garnered in competition for the Topps All Star Rookie Team.

Bateman will “be one of the best [backstops] in the game.”[fn]“Big Time Loaded to Hilt With Talented Catchers,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1964, 2.[/fn] This was the consensus opinion as the catcher, following a brief stint in the Puerto Rican winter league, prepared to build upon his inaugural campaign. But a .143 average in spring training seemingly telegraphed Bateman’s 1964 season. He did not collect his second home run of the season until June 7 — a lusty drive clearing the scoreboard clock in Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field — while his average hovered below .200. Houston turned to a platoon with catcher Jerry Grote whose .181-3-24 batting line did little to improve the team’s offense. The pair quit rooming together on the road because, as Grote joked, “There weren’t any base-hits in that room so we figured we had to do something.”[fn]“.45s Splintering N.L. Walls With Cannonball Shots,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1964, 26.[/fn] A lack of plate discipline had Bateman swinging at bad pitches. When he slumped in July — .188 in 32 at-bats — Houston optioned him to Oklahoma City (Class AAA). Bateman’s short stay in the Pacific Coast League proved productive, including a three-homer game against the Indianapolis Indians on August 6. He rejoined the Colt .45s in September and delivered game-deciding hits in two contests. But these were a mere two hits in 21 at-bats that lowered his season line to a disappointing .190-5-19. In November Houston drafted Ron Brand from the Pittsburgh Pirates in an effort to bolster their sagging catching corps.

In 1965 the newly dubbed Houston Astros were poised to chalk Bateman’s previous campaign to the sophomore jinx. Prior to spring training current manager Lum Harris offered, “[Bateman] “will play back to his promise of 1963 … [he] got to pressing and was a little confused last season … He’s a better player than he showed [and has] the potential to be the long-ball-hitting right-handed batter we need.”[fn]“Draftee Brand May Grab No.1 Astro Mitt Job,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1965, 10.[/fn] When Bateman reported to camp overweight — what became a career-long concern — Houston enrolled him in a rigid two-week weight-loss program. Meanwhile coaches worked closely in altering Bateman’s batting stance, spreading his feet to avoid a big stride in hopes of cutting down on his strikeouts. The results were immediate. On May 1, 1965 the franchise that knew only 96-loss campaigns in its three years of existence suddenly found itself in first place largely due to Bateman’s production. On April 18 his two home runs accounted for Houston’s entire offense in a 3-1 victory over the Pirates. Initially platooned with Brand behind the plate, Bateman moved into the starting role on April 23 sporting a .400 average while collecting three of the team’s first four homers.

Inexplicably, Bateman’s hot hand turned instantly frigid. A groin muscle pull only added to his frustrations as he managed a mere six hits in 59 at-bats. Losses mounted as Houston finished with another 90-loss season. When Bateman struck out three times in five June at-bats he was once again optioned to the Oklahoma City 89ers. As bafflingly cold as his bat was in Houston, Bateman surged with the 89ers:

- June 24: Two homers in a 12-3 win over Tacoma

- July 25: Four RBIs in a 7-2 win over Denver

- August 1: Four-for-five with a home run and four RBIs in a 9-8 slugfest over Salt Lake City

- August 8: Two homers, including a grand slam, in a 7-3 win over Hawaii

In August Bateman’s dedication was evidenced when he was knocked unconscious by a pitched ball to his temple — the third time that season he had been hit in the head. Rushed to the hospital for X-rays, Bateman returned to the ballpark and was found warming up a relief pitcher in the eighth inning.

Despite just 266 at-bats Bateman placed among the team leaders with 21 home runs and 66 RBIs as he led the 89ers to the Pacific Coast League championship. The National Association of Baseball Writers chose Bateman as the Topps AAA All-West All Star catcher. His hot bat proceeded south as he paced the Venezuelan winter league in RBIs while leading the La Guaira Sharks to a championship season. Bateman was considered “the league’s most dangerous hitter in the clutch.”[fn]“Hernandez Flexes Muscles, Ties Mark With 3 Home Runs,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1966, 27.[/fn] The New York Mets offered lefty starter Al Jackson in a multi-player trade involving Bateman that the Astros pulled out of at the last minute.[fn]A trade for Grote was executed October 19, 1965 but the Mets first choice was Bateman.[/fn] Houston believed — based on his recent success — Bateman “remain[ed] the No. 1 hope behind the plate.”[fn]“Morgan, Staub and Wynn Left Astros Cheering,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1965, 22.[/fn]

In April 1966, as if in response to these hopes, Bateman said, “I think I can hit .260 in the majors,” adding “I would like to hit 20 or more home runs.”[fn]“Not-So-Brash Bateman Cuts Swat Forecast,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1966, 14.[/fn] Though he fell short of his home run goal, Bateman would post his finest campaign. The surge started with the Astros’ first intrasquad game in spring camp when Bateman struck the game-winning homer. His .280 spring training average and team-leading home run pace served as a springboard for Bateman’s franchise single-season record 16 homers by a catcher.[fn]This record was tied by Jason Castro in 2013 and stood through 2014.[/fn] He placed among the team leaders in nearly every offensive category and teammates took great umbrage when Bateman was omitted from the National League All-Star team.

With a strong penchant for temper displays, Bateman led his teammates with six ejections. His blunt, earthy humor earned him the title of the clubhouse’s laureate wit while his leadership drew lavish praise. “On the field I’d say he’s the leader of this team,” claimed Hall of Famer Joe Morgan.[fn]“Space Shot By the Ambitious Astros,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1966.[/fn] Hurler Bob Bruce cited Bateman for contributions to his career-best 1964 campaign while another Hall of Famer, Robin Roberts, exclaimed, “This fellow is just a real fine catcher — I’m really impressed with the job he’s doing.”[fn]“Astros Booming Bateman for Top Mittman Honors,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1966, 8.[/fn] (This despite Bateman having again led the league in passed balls and errors committed as catcher.) Agreeing to sit only when forced by injury, Bateman refused all other offers of rest — a factor contributing to his second-half dip. On May 14 he was hospitalized after being knocked unconscious by a bat’s whiplash. On July 29 Bateman sustained an injury to his right hand and missed seven games behind the plate. The day after his return he took a Don Drysdale fastball to his left hand and missed another game. But these instances were few as Bateman’s durability afforded single-season career highs in average (.279), doubles (24), homers (17) and RBIs (70, second behind Joe Torre for NL catchers).

In the offseason Houston dangled Bateman in hopes of luring a solid slugging left fielder. A trade for Boston’s Don Demeter was reportedly consummated until the deal fell apart over the supplemental players. Bateman welcomed a trade to a team with a shorter left field porch, feeling it could enhance his home run output. Meanwhile Bateman was being challenged for tax evasion. He had returned to the La Guaira Sharks over the winter only to discover that he was one of a dozen players being investigated by the Venezuelan government for accepting payments under the table to play. Though nothing came from these allegations, Bateman would cite the mental fatigue from winter ball — including perhaps the stress from the tax investigation — for contributing to his dismal 1967 season.

Bateman’s start appeared promising. He carried a .308 average into an April 16 game against the Cardinals when he connected off Bob Gibson for a two-run blast. But over his next 76 at-bats Bateman collected only eight hits, sinking to a season-low .143. The coaches offered advice – they’d say he was moving around in the box, taking his weight off his back foot, jamming himself on inside pitches — to no avail. When Bateman turned things around in June — .308 in 26 at-bats — fate intervened. On June 11 he fractured his ankle on the base path and was projected to be out six weeks. Bateman rushed his recovery, returning to the team July 4, but he could not regain the hot bat of June. Bateman suffered a back injury that sidelined him periodically through the summer and waylaid him completely after September 1. In October the frustrated catcher requested a trade when the Astros were reportedly looking to catching prospect Hal King for the 1968 season. The club tried to accommodate Bateman but received little interest following his .190-2-17 line in 252 at-bats.

In 1968 King received the starting nod for the Astros with Bateman intended for use against lefty hurlers. But when King faltered in early May Bateman began receiving the bulk of the catching responsibilities. No sooner had he done so when Bateman was victimized by a series of injuries. He attempted to play through a badly bruised and swollen finger on his right hand until the pain prevented Bateman from gripping a bat. On May 31 he reinjured his back running out a double — “I’m just not used to running so fast,”[fn]“Morgan Loss Looms Larger Daily As Weak Attack Handcuffs Astros,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1968.[/fn] he joked — and missed four games. Bateman sat three games after taking a foul to his big toe on June 17, an additional six games after spraining his ankle on July 19. Though he avoided serious injury on August 7 when an opponent’s spike was driven through his shin guard, Bateman missed the season’s last ten games when his back gave out again.

Though limited in appearances, Bateman tied a major-league record on July 14 with nine consecutive putouts. Bateman also captured his first career stolen base after misreading the sign from the dugout. Despite Cardinals Hall of Famer Lou Brock’s declaration that he possessed the strongest arm in baseball baserunners ran freely on Bateman. The Astros experienced its first season in the cellar due largely to a major-league low 66 homers. When it was suggested to Bateman that the Astros consider burning their bats he quipped, “While we’re at it, we might burn a few gloves, too.”[fn]“Comic Cuellar Keeps Astro Pad at High Pitch,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1968, 19.[/fn]

On October 11 the Astros acquired veteran catcher Johnny Edwards from the Cardinals in a four-player exchange, thereby telegraphing that Bateman, thought to be among Houston’s protected players, was suddenly available in the October 14 expansion draft. With their third pick — 12th overall — the Montreal Expos selected the Houston catcher. Bateman instantly recognized the opportunity to step into a starting role for the newly formed club but could not resist the urge to deliver a parting shot to his former employer: “This is the greatest organization in the world for making players mad and hav[ing] them not do their best as a result.”[fn]“Astro Shelf, Once Catcher-Rich, Now Nearly Bare,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1968, 36.[/fn]

Due to a dearth of quality catchers in the National League the Expos were immediately besieged with offers for Bateman. The most aggressive bids came from Atlanta Braves general manager Paul Richards who’d recently parted with Hall of Famer catcher Joe Torre (it was Richards’ 1962 comparisons to Gabby Hartnett that helped launch Bateman’s career). But the Expos did not budge. Bateman reported to spring training in the best condition of his career. During the Grapefruit League exhibitions he led the team in batting and RBIs and early projections tabbed the catcher as the team’s clean-up hitter.

Due to a dearth of quality catchers in the National League the Expos were immediately besieged with offers for Bateman. The most aggressive bids came from Atlanta Braves general manager Paul Richards who’d recently parted with Hall of Famer catcher Joe Torre (it was Richards’ 1962 comparisons to Gabby Hartnett that helped launch Bateman’s career). But the Expos did not budge. Bateman reported to spring training in the best condition of his career. During the Grapefruit League exhibitions he led the team in batting and RBIs and early projections tabbed the catcher as the team’s clean-up hitter.

On April 14, 1969, excitement reigned throughout Montreal as the Expos prepared for their inaugural home opener at Jarry Park. Bateman received the ceremonial first pitch from Quebec Premier Jean-Jacques Bertrand, officially welcoming big-league baseball to Canada. Three days later Bateman caught the Expos’ first no-hitter, thereby etching his name in the record books as the only catcher to receive the first no-hitter for two franchises. Though garnering praise for his work with the young pitching staff, Bateman could not buy a hit, going just .179 through April. Relegated to a reserve role, he received his next starting assignment May 14 and lashed a home run on the first pitch he saw. The blast unleashed a .333 pace in 32 at-bats, an indication Bateman was emerging from his slump. But much like the fate that befell him in 1967 when injury thwarted his offensive surge, the injury bug resurfaced. On May 29 a foul tip split his finger. The consummate team player appears to have come back earlier than warranted when, upon his July 4 return, he managed one hit in 17 at-bats. Ron Brand, also selected from Houston in the expansion draft, received the majority of time behind the plate through the season’s remainder as Bateman finished the once-promising campaign with a .209-8-19 line in 235 at-bats.

In the offseason Montreal started pursuing another catcher via trade. In an effort to dissuade this effort, Bateman returned to Venezuela for the first time in three years to convince his skeptics that he remained a viable candidate. He succeeded. Bateman placed among the league leaders in nearly every offensive category. The only blemish appears to be a fine levied against the fun-loving catcher’s dugout antics that were deemed abusive to both sportswriters and his Aragua teammates. As events developed, this would not be the last time Bateman found he was short in the wallet.

The weight issues that haunted Bateman throughout his entire career proved costly when he reported to spring camp in 1970. The Expos were convinced that Bateman’s excess weight had contributed to his pedestrian performance the preceding year and demanded slimming to 200 pounds. When Bateman weighed in at 208 pounds, he was fined $800 — $100 for each excess pound; during Bateman’s three-plus years in Montreal he paid more than $2,500 in weight-related fines. Bateman miraculously got down to 198, a figure he’d likely not seen since shortly after high school. Intended as a compliment, Washington Senators manager Ted Williams, in his typically blunt style, said, “[Bateman] used to be a slob. Now look at him.”[fn]“Hustling Bateman Frets in Hospital Bed,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1970, 24.[/fn]

Excluding tying a dubious major-league mark by striking out twice in the same inning (August 29, 1971), the svelte Bateman produced his finest play over a two-year span. On July 2, 1970, he collected his first major-league grand slam while establishing an Expos single-game record seven RBIs (later surpassed). Two months later he smacked the last home run in the fabled history of Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium. From 1970 to 1971, Bateman placed among Montreal’s team leaders in hits, doubles, homers and RBIs.

He moved to Montreal year-round, finding offseason work at the Seagram’s distillery. At manager Gene Mauch’s insistence, Bateman declined an invitation to travel around the world entertaining U.S. forces. But he did not seek Mauch’s approval on November 6, 1970, when the less-than-pleased manager spied Bateman on television accompanying the Quebec police in a raid on a paramilitary cell. Bateman found time to participate in less risky events as well, including golf tournaments and other charitable events that endeared him to the local populace. In 1970 Bateman was chosen as the Sports Chairman of the Canadian Kidney Foundation when it was discovered Bateman played his entire professional career with one kidney. The catcher claimed the removed organ was lost as a result of a high school football injury but, unbeknownst to the Foundation, Bateman never played football. Bateman was savvy enough to realize the honor might not be entrusted to him had he been completely truthful — the lost kidney was the result of a drunken barroom tumble —so he made up the high school injury.

In September 1971 the Expos began inserting 22-year-old catching prospect Terry Humphrey into the lineup (a fellow-Oklahoman, Bateman and Humphrey were born nine years and 45 miles apart). The loss of play upset Bateman and exacerbated the already corrosive relationship that existed between him and his equally headstrong manager. Bateman and Mauch nearly came to blows in the lobby of the team’s hotel in St. Louis during the season’s final road trip. When Humphrey won the starting catcher’s role the following spring the Expos began dangling Bateman in trade. Relegated to the farthest end of the bench, Bateman captured a mere 18 appearances through June 14, 1972, when Montreal found a willing trade partner in Philadelphia (equally anxious to rid themselves of disgruntled catcher Tim McCarver). Bateman received the bulk of time behind the plate for the last-place Phillies. He was lauded by Hall of Famer Steve Carlton for his mechanics and game-calling during the lefty’s phenomenal Cy Young Award season.[fn]Carlton with Bateman behind the plate: 20-4, 1.60; without: 7-6, 2.83.[/fn] But in September, in a near-repeat performance of the preceding year, the club called-up prospect Bob Boone. After Boone demonstrated his readiness at the major-league level Bateman was again dangled in trade. Finding no takers, and despite Carlton’s vehement protests, Bateman was given his unconditional release on January 15, 1973.

Bateman returned to Houston and played fast-pitch softball (as he had prior to signing with the Colt .45s). He teamed with the Texas state amateur softball champion Houston Bombers and in 1977 began touring with the four-man softball exhibition team The King and His Court, founded in 1946 by its pitcher, Eddie Feigner. Bateman stayed with the team over several years, earning more money than at any time during his major-league career. He powered 179 homers over 221 games in 1979, 190 dingers the next year. He had worked offseasons alongside teammate Dave Giusti installing cabinets in apartments but found further employment in chemical and manufacturing plants. In the 1980s, after returning to Oklahoma, Bateman sold insurance.

Bateman became a coach and director of the American Legion in Sand Springs, Oklahoma. When time allowed Bateman also enjoyed golf, hunting and fishing. He was slowed in his later years only by the number of times he was hobbled following knee surgeries before contracting more serious health concerns. Bateman’s remaining kidney malfunctioned and he was forced to undergo dialysis three times weekly. The grueling blood-cleansing procedure affected other organs and Bateman succumbed to heart disease on December 3, 1996. He was buried beneath a large commemorative headstone in Woodland Memorial Park in Sand Springs, Oklahoma, survived by two ex-wives, three children and seven grandchildren. In 2014 his baseball prowess appears to have extended to his grandson, Carson Teel, a walk-on pitcher for the Oklahoma State Cowboys.

Bateman ended his 10-year major-league run with 81 home runs and 375 RBIs averaging less than 102 games per year – numbers seemingly incongruous to the compliments from and comparison to varied Hall of Famers.[fn]Due to a marketing mishap Bateman’s rare 1963 Pepsi Cola-issued baseball card is priced among collectors to that of a Hall of Fame player.[/fn] Injuries played a part as did inconsistent play from the native Oklahoman. Paul Richards said in reference to the very young players that populated the 1964 Houston roster, “We knew they were in over their heads.”[fn]“Colts Seeks Better Ammunition From Bateman, Staub and Wynn,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1964, 14.[/fn] With one year of Class C experience preceding his promotion to the majors, Bateman acknowledged this stating, “I was too young and knew it … I wasn’t ready.”[fn]“Houston Astros,” Sports Illustrated, April 18, 1966.[/fn]

Through a letter-writing campaign from an unknown entity in central Texas the Houston Colt .45s wound up with their 1963 starting catcher. With few choices open to them, the expansion club rushed Bateman to the majors. It remains for others to speculate how Bateman’s career may have advanced with proper development. One thing is certain: Baseball provided a safe, productive venue for a youngster whose life might easily have gone down a very different path.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the following: Pamela Teel, Bateman’s daughter, for recollections of her father; Julia Skrinde Otto, a distant cousin whose Bateman family research proved invaluable; Ken Webster, author of the John Bateman twitter-diary; SABR members Gale McCray (Bateman’s childhood friend), Mark Wernick, and Bruce Slutsky; and Mark Pattison for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

Websites

ancestry.com

baseball-reference.com

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=13317740&ref=acom

http://www.kingandhiscourt.org/playerphotos.php

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9cdf038d

http://sabr.org/research/1963-pepsi-cola-colt-45s-baseball-card-set

http://www.si.com/vault/1966/04/18/614498/houston-astros

Books

Murff, Red with Mike Capps. The Scout: An Insider’s Story of Professional Baseball in Its Glory Days. (W Publishing Group, 1996).

Full Name

John Alvin Bateman

Born

July 21, 1940 at Fort Sill, OK (USA)

Died

December 3, 1996 at Sand Springs, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.