John Knight

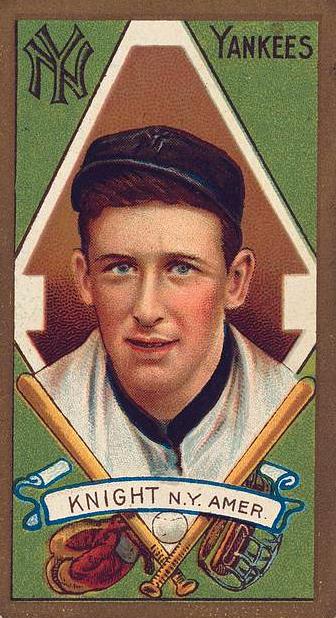

Jack Knight was a ballplayer who could recite any of Rudyard Kipling’s poems and also enjoyed watching surgeons perform operations. John Wesley Knight was his proper name and he was born in Philadelphia on October 6, 1885. One of his brothers was a doctor and he told at least one writer that if he could start over again he’d have become a doctor himself rather than play baseball.[1] Knight’s nickname was “Schoolboy”, as he was signed straight out of high school by Connie Mack from the championship team of Central High School in Philadelphia. He may have taken some pride in the nickname. On a player questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame, on the line for “nickname” he wrote in “Schoolboy” and then, above it, added “The original”. He later attended New York College (studying dentistry in the offseason of 1911-12) and then the University of Pennsylvania, obtaining two years of credit,s enough to earn a certificate of admission to the third year science program of any other university.[2]

Jack Knight was a ballplayer who could recite any of Rudyard Kipling’s poems and also enjoyed watching surgeons perform operations. John Wesley Knight was his proper name and he was born in Philadelphia on October 6, 1885. One of his brothers was a doctor and he told at least one writer that if he could start over again he’d have become a doctor himself rather than play baseball.[1] Knight’s nickname was “Schoolboy”, as he was signed straight out of high school by Connie Mack from the championship team of Central High School in Philadelphia. He may have taken some pride in the nickname. On a player questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame, on the line for “nickname” he wrote in “Schoolboy” and then, above it, added “The original”. He later attended New York College (studying dentistry in the offseason of 1911-12) and then the University of Pennsylvania, obtaining two years of credit,s enough to earn a certificate of admission to the third year science program of any other university.[2]

Jack’s parents were James Knight Jr. and Annie Knight, and Jim Knight had apparently been a “great pitcher” in his day in the early 1880s, not in the record books but known to Ben Shibe, who became owner of the Philadelphia Athletics. An unattributed clipping in John Knight’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame contains this tidbit: Thirty years ago old Jim Knight was some pitcher. He was the star of a team Uncle Ben Shibe, new owner of the world’s champion Athletics, owned, and which played only on Saturdays in those old days when baseball was really in its infancy. One day Jim’s arm went back on him and to the regret of Shibe the star pitcher had to quit the team. ‘Some day, Ben,’ said Jim Knight on parting, ‘I’ll send you a downright smart ball player.’” Jim Knight’s parents had come from England. He worked as inspector of state factories.

Jim’s son Jack began his professional career in the major leagues, first spotted in 1904 by the Philadelphia Athletics’ first baseman Harry Davis while Davis was out of action due to a sprained leg. He saw Knight at a game in West Chester, Pennsylvania (playing as a third baseman for the Brandywines under the name of “Ryan” since he was still a student at Central High at the time) and recommended him to Connie Mack as worth a trial. [3] Mack signed him on January 3, 1905 and Knight went to spring training with Shibe’s Athletics. Knight played second base in three of the four preseason “city series” games against the Phillies, as a “capable understudy” for Danny Murphy and had a hit in every one. [4]

On Opening Day, April 14, Knight played against the visiting Boston Americans (pennant winners in 1903 and 1904). That wasn’t the original plan, but Athletics shortstop Monte Cross had a bone in his right wrist broken by one of Cy Young’s pitches in the second inning. Umpire Silk O’Loughlin seemed a bit arbitrary this day, and would not let Cross let him take first base. Cross then singled, but had to leave the game and Knight came in to replace the ten-year veteran. Knight singled in the fourth inning, and was 1-for-3 on the day. The final score was 3-2, though according to the Boston papers (the other papers didn’t see it the same way) Chief Bender walked the bases loaded and his pitch on a 3-2 count was six inches off the plate, but umpire O’Loughlin turned and walked off the field indicating that it was a third strike, thus ending the game.

After the first eight games, Knight led the American League with a .407 average. He was 6-feet-2 (2 ½, according to the player questionnaire he completed for the Hall of Fame, weighing 180 pounds), and considered by some to have been the tallest man to have played shortstop at the time. A month and a half into the season, Sporting Life wrote, “Young Jack Knight is still holding his own in batting and fielding, and consequently the activities of Monte Cross, whose had is again all right, are confined to coaching. Monte, far from being grieved, is broad-minded enough to feel pleased with the ‘Kid’s’ success and constantly gives him valuable advice.” [5] That Knight was a local boy, still 19, didn’t do a thing to hurt his popularity.

Knight was off to a terrific start, but one that proved difficult to sustain at such a high level and, quite coincidentally, Cross resumed as the mainstay at short after Knight was hit in the hand in early July…by a Cy Young pitch. He was back within two weeks and they’d split the season more or less evenly. Connie Mack cited Knight’s early work as helping the Athletics: “Connie says it was largely due to the youth’s stickwork at a time when the other had not got into their stride that the Athletics went to the top.” Indeed, the Athletics won the American League pennant. Knight finished with a .204 average and 29 RBIs, with three home runs in 325 at-bats. Monte Cross hit .266, coincidentally the same average as his brother, third baseman Lave Cross. Knight did not play in the World Series, which was won by the Giants in five games.

Lave Cross was sold to Washington two days before Christmas, and Knight took over his slot at third base – though in February Buffalo apparently put on a push to acquire him, and Mack had intended to have Rube Oldring play third base. Knight responded that he’d jump his contract and play in the Tri-State League if he was farmed out. Oldring was unable to play in the early going, so Knight did play the season through, sharing duties at third, hitting .194 in 74 games, with 20 RBIs. Monte played short, hitting .200.

He started the season at third base in 1907, as an everyday player, and was hitting .209 through 40 games, when he was traded to the Boston Americans on June 7 for their third baseman Jimmy Collins, a great player from earlier days but one who was struggling in Boston – in part with personal devils – and had had to be replaced as manager to bring about some semblance of team harmony. The Athletics got one good year out of Collins. Knight, with the Red Sox, played in 98 games and hit what was, for him, a career-high .217 to that point (he was still just 21, but in his third season in the majors).

In December, Knight learned that he was the “player to be named later” in an August 10 deal between Boston and Baltimore. Boston had obtained Fred Burchell for cash (Baseball Magazine said it was $10,000) and the PTBNL. Knight cleared waivers and was sent to the International League Orioles on December 28. The Red Sox slotted in Harry Lord at third base for 1908. Knight had his first experience of minor-league ball, playing a full 140 games and hitting .228, with nine home runs.

There was another August deal done; on the 20th, the New York Highlanders purchased his contract from Baltimore, but let him complete the season with the Orioles. In Buffalo, they called him “the handicap man” because he was a major-league player working in the minors; Sporting Life praised his defense: “While not a great hitter, Knight kills more hits than he makes. He is not a showy fielder, but like Lajoie, he covers a vast amount of ground without apparent effort. On account of his height, Knight gets balls that many of his contemporaries never could reach.” [6]

It was back to the major leagues for three seasons with New York (1909-1911), determined to prove his worth, and he became a distinctly-improved hitter (.236, then .312, and .268, with a career-best 62 RBIs in 1911). He’d not been in the best of health in 1909, but came into his own in the two years that followed. He played all four infield positions in each of the three years, though more than half of the time it was at short. When he wasn’t playing infield, he was playing piano in the hotel lobbies or going to concerts. He also reportedly had a “fine bass voice” and had been the leader of the glee club when he was in school. He was also an enthusiastic of the newly-popular automobile .[7] In June 1910, Knight married Helen Wills Barclay.

He’d long been considered an excellent fielder, adept at any infield position – with even some debate as to which position he played best – but why did he suddenly start to hit? Sporting Life shrugged, “[H]e seems to have suddenly discovered the elixir of swatology.” [8] Two weeks later, the publication somewhat unhelpfully added that he appeared to have changed his style of batting. In his final year with New York, Knight began to show some inconsistency in his fielding, but manager Hal Chase (for whom Knight had filled in at first) thought there wasn’t a better first baseman in the business.

Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators had been inquiring about Knight throughout much of 1911; he finally landed his man and consummated a trade on February 17, 1912, sending Gabby Street to New York and, five days later, including Rip Williams in the deal as well. The Highlanders had a new manager, Harry Wolverton, and he wanted someone who he believed would be more reliable in the field. His contract with Washington was a high $4,000 a year, and he was said to have not reported in good physical condition. He hit .161 in 32 games and on June 28, having not used him that much, he was sold to the International League’s Jersey City Skeeters. He had been “unable to get into his stride. He could not play up to his standard, and caused the loss of games instead of the winning of them. When a man agrees to deliver a ton of coal and then offers a pint of peanuts instead there is not much chance for him to collect the price agreed upon for the coal. Knight should get in shape for next year’s start, and it is to be hoped that he will ‘come back’ if he does so.” [9] Even with Jersey City, in Double A baseball, he got only hit .210, in 78 games. He couldn’t have been highly motivated, with his pay cut in half, to $2,000, and the Baseball Fraternity took up his case. There was no contest regarding the matter of showing up out of shape, which complained that there were fines and suspensions which should have been used to penalize him financially, rather than cutting his pay.[10]

The year 1913 was split, the first 77 games with Jersey City (revived at the plate and hitting .270) and then, after a trade to the Yankees on July 13 for Babe Borton and cash, 70 games with New York (hitting .236). It was his last year in the majors; he was sold to Toledo on December 8, 1913. What was lacking at this point in his career was said to be ambition. The November 13 Sporting Life had written, “It looks very much as if Jack Knight is due for the blue envelope again. Here is a player who, if it were possible to instill into him such a thing as ambition, he would be one of the wonders of the age. But, alas! It’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks.” Knight was only 27. Other reports ascribed to him a “lackadaisical disposition” and a “lack of ginger” which “has killed his chances every time and [made him] one of the biggest disappointments in the game.” [11] And yet he had another 15 years of baseball in him.

Knight never played for Toledo. His contract was passed on and he played shortstop in 1914 and 1915 for Cleveland, a team that changed its name from the Bearcats to the Spiders. Both the Toledo and Cleveland teams were owned by Charles Somers, one of Ban Johnson’s biggest backers in the founding of the American League. Knight hit .308 the first year and .282 the second, during which he served as manager for the seventh-place Spiders. After the season was over, he picked up some extra work covering the 1915 World Series for a Cleveland newspaper. And after that he proposed a national golf tournament featuring baseball players competing after the season was over. [12]

Roger Bresnahan bought the Cleveland club in the American Association (but converted it to the Toledo Iron Men, and decided to manage it himself). The Minneapolis Millers reached out and signed him, and it was on to three seasons with the Millers, all three at first base (1916-1918).

In 1918, the season was curtailed – as was all of baseball – because of the world war. The team played 76 games before the season was called to conclusion. Knight, however, only appeared in 27 of them. When he did, he did well (.280), a step up from the two prior years (1916 was .255, and 1917 was .274).

After the war, it was baseball out west for Jack Knight. From 1919 through 1928, he played in the Pacific Coast League and the Western League. In 1919, it was with the Seattle Rainiers and then four years with Oakland. Two years with Denver (1924 and 1025) in the Western League, and the next two with Sacramento, and a final year back with the Denver Bears in 1928. Over the course of the ten seasons, he hit for a .313 average. His best year in the Double-A P.C.L. was 1921, when he hit .342 with 19 homers and in Single-A ball in 1925, when he hit .352 with 19 home runs. He was 42 years old when he stopped playing.

At one point in his early days, he took a job at the City Surveyor’s office in Philadelphia. His studies of dentistry indicate other talents and interests. After baseball, Jack became an accountant with Bethlehem Steel, and later an auditor and office manager for a corporation in San Francisco.

There was a manager named Jack Knight in the Cleveland system who ran their Flint team and the Indians’ Northern League affiliate, the Fargo/Moorhead Twins, from 1937 through 1939, but it was a different Jack Knight. [13]

Knight lived a long life. Predeceased by his wife Helen, he died on December 19, 1965 in Walnut Creek, California, of cardiorespiratory failure.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Knight’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Bill Francis.

[1] “What You Don’t Know About Big Men in Sports, No. 8 – Jack Knight”, unattributed news clipping in Knight’s Hall of Fame player file. One of Knight’s brothers was a doctor,

[2] All this, according to Knight’s player questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

[3] “What You Don’t Know…”, op. cit., and Sporting Life, January 7, 1905

[4] Sporting Life, April 17, 1905

[5] Sporting Life, June 10, 1905

[6] Sporting Life, October 24, 1908

[7] Sporting Life, August 28, 1909 and September 11, 1909

[8] Sporting Life, September 24, 1910

[9] Sporting Life, November 16, 1912

[10] Baseball Magazine, March 1913. To the extent that Knight had a case, it went nowhere. See Sporting Life, January 23, 1915.

[11] Sporting Life, February 1, 1913 and December 29, 1913

[12] American Golfer, December 1915

[13] The Sporting News, July 31, 1941

Full Name

John Wesley Knight

Born

October 6, 1885 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

December 19, 1965 at Walnut Creek, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.