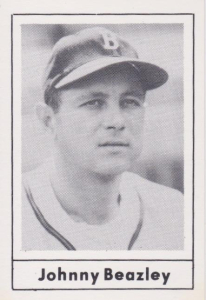

Johnny Beazley

For most of pro baseball’s first century, when a “sore arm” sidelined a pitcher for an extended period, it began a descent in skill too often resulting in an untimely exit from the game. Frequently, these players were victims of whisper campaigns, having their courage and valor called into question. Surgeons were unable to repair their defects, and they faded quickly from the scene, ultimately to appear on lists of hurlers who had great seasons but brief careers.

For most of pro baseball’s first century, when a “sore arm” sidelined a pitcher for an extended period, it began a descent in skill too often resulting in an untimely exit from the game. Frequently, these players were victims of whisper campaigns, having their courage and valor called into question. Surgeons were unable to repair their defects, and they faded quickly from the scene, ultimately to appear on lists of hurlers who had great seasons but brief careers.

As a result of the era in which he pitched, John Andrew Beazley, Jr. would not benefit from the progress in medical therapies and surgical procedures for his injured arm. As a rookie in 1942, “Beaze” had pitched brilliantly for the St. Louis Cardinals during the regular season and World Series, posting two victories over a supreme New York Yankees ball club and rightly earning the nickname of “Yankee Killer” as St. Louis captured the Series. He answered the call of war shortly thereafter, and when he returned, his arm and career were on a downward trend. His lifetime 31-12 record is a most impressive one, but also leaves one wondering what could have been.

Johnny Beazley was born on May 25, 1918, in Nashville, Tennessee, the son of John Andrew and Mattie Sue Robertson Beazley, known as Sue. From 1925 to 1932, young Johnny attended the Barker School in Birmingham, Alabama. Returning to Nashville, he enrolled at Cohn Junior High in West Nashville. While he was still young, his father died.

By the age of 16, Johnny was passionate about boxing. An article by Dick Farrington in The Sporting News explained that Beazley had a friend who was a Golden Gloves champion, and Johnny frequently worked out with him. His buddy eventually won the Southern Amateur Light Heavyweight Championship, and Beazley served as his cornerman whenever he boxed. It was Johnny’s ambition to become a fighter too, but when he told his mother of these intentions, she put her foot down. “I don’t want you going around with your nose on the back of your head,” she told her young son. Earlier, Johnny’s younger brother, Felix, had died because of an injury suffered during a football game at Nashville’s Cohn High School, so her objections to “rougher” sports were understandable. Mom had her way, and when Johnny heeded her plea and forsook boxing for baseball, she had no objections.1

Johnny did not play much baseball before high school. He always took jobs during the summer months — as a delivery boy for a local drugstore, delivering orders to customers on his bicycle, or clerking in a grocery store six days a week. It was out of necessity, as he had to find work and earn income for his mother. She had now been a widow for several years, and Johnny, her only living child, had to help provide for her.2

There was time for athletics in high school, though. At Nashville’s Hume-Fogg High, baseball coach Fred “Ox” McKibbon listened to some of Johnny’s teammates who saw a boy with pitching talent and moved him from the outfield to the mound. Beazley quickly became the team’s number one hurler, and recorded a 9-0 shutout over Franklin High in his first start. He took to other sports as well, and finished at Hume-Fogg as a four-letter man.

Upon graduation, Beazley went to a baseball school conducted at Nashville’s historic Sulphur Dell ballyard. Jimmy Hamilton, a scout for the Cincinnati Reds, managed the business office for the school (“tuition” was $25, but it was waived for Nashville residents); while the instructors, all current or former big-leaguers, were Tom Sheehan, George Kelly, Charlie Dressen, Gilly Campbell, Hub Walker, and Paul Derringer. Hamilton’s job was also to sign any decent prospects for the Reds. Of the 40 or so who attended the school, Johnny was the only player signed. He was inked to a contract with the Nashville Vols of the Southern Association in the fall of 1936, when he had just turned 17 years old. Cincinnati had a working relationship with Nashville. Beazley was sent the following spring to the Leesburg Gondoliers of the Class D Florida State League.3

Leesburg was managed by former Pirates pitcher Lee Meadows. Johnny was a mediocre 4-3 for Leesburg with a 3.96 ERA, and in midseason, he was moved to Tallahassee in the Georgia-Florida League in the hopes that he might prosper under manager Dutch Hoffman. His performance there was worse (1-7, 4.50 ERA) but Hamilton still believed in his potential and moved him to Lexington, Tennessee, in the Kitty League. Playing for his third ballclub of the year, Johnny won a couple more games but still had a mediocre record (2-5, 4.50 ERA). All told, the rookie was a disappointing 7-15 for the ’37 season.

In 1938 Beazley began the year at Greenville in the Class C Cotton States League. Reds scout Hamilton thought he looked great in exhibition games this time, but Johnny hit a roadblock when the regular season got under way. He began 2-4 with a 7.63 ERA, and not long after the season started was declared a free agent because of a technicality over his transfer from Lexington to Greenville. Disgusted with his pitching, Beazley decided to go home to Nashville. In July, he accepted a $250 bonus to sign with Abbeville in the Class D Evangeline League, but he had a hard time getting going there as well and returned home a second time. Only at the urging of Abbeville manager Jess Petty, the former Brooklyn pitcher known as “The Silver Fox,” did Johnny return and finish the season. His skipper’s confidence must have helped, as Beazley won several games and put up a better earned run average (6-8, 3.27 ERA) down the stretch.

Still more challenges were to come. After the ’38 season, Beazley’s contract was sold to the New Orleans Pelicans (scout Bob Dowie was instrumental in his acquisition) of the Class A1 Southern Association, a considerable jump in caliber.

At the end of his first month with New Orleans, Beazley injured his elbow. He had pitched just 25 innings in 10 appearances for the Pelicans, with a woeful 1-3 record and a 9.36 ERA. He walked 13 batters and allowed 27 runs on 39 hits during this brief stint, and was thus sent packing again — this time to Montgomery in the Class B Southeastern League. There he pitched only one game before being sent home yet again to rest his arm. Apparently only a fierce determination and encouragement from his coaches along the way kept Johnny in the game. Sue Beazley, his mother, also cited Vanderbilt coach Bill Schwartz, who had Johnny pitch batting practice each spring and offered a number of tips.4

Reporting back to New Orleans in 1940, Johnny was now a St. Louis Cardinals farmhand because the Pelicans had signed a working agreement with the Cards. After allowing 13 runs in nine innings over four games for the Pelicans with no decisions, he was moved back to in B ball and hurled only moderately more successfully for the Sally League’s Columbus Red Birds (5-3, 5.17 ERA). While with Columbus, he injured his back and returned home to Nashville to recover. Still struggling to gain his earlier promise, he was sent to the Montgomery Rebels in the Southeastern League and finally showed some real improvement — going 4-2 with a 2.04 ERA in eight games. Beazley’s rebound during his final Class B stop of the year foreshadowed his return to New Orleans and his development into a major league quality pitcher during 1941.

The ’41 season was a pivotal year for Beazley. While in New Orleans, he finally learned how to truly pitch under Pelicans manager Ray Blades. Previously, Johnny said later, he had only tried to “fog the ball past the batters. It didn’t work, but I thought I knew it all.” Blades convinced the still-young Beazley that “there was more to pitching than just throwing the ball” and taught him to pitch to locations and change speeds.5 He got a lot of work, pitching in 44 games (including 31 starts). Injury-free at last, Beazley went an impressive 16-12 with a 3.61 ERA over 217 innings.

When the Cardinals expanded their roster in September, he was called up to “The Show.” The Cardinals were were battling the Brooklyn Dodgers for the National League pennant, but surrendered the flag to the Bums during the final week. Beazley, now 23, made his major-league debut on the meaningless last day of the regular season, starting against the Chicago Cubs. His mound opponent was another late-season rookie call-up, Russ “Babe” Meers, also making his initial big-league appearance. Meers and Beazley had battled each other during the 1941 Southern Association season, and here they battled again. Meers lasted eight innings, allowing only five hits, but Beazley scattered 10 hits while pitching a complete game and securing his first major league win, 3-1. “I was lucky I had a manager who was so patient,” he later said in appreciation of Blades. “Otherwise I wouldn’t be up here winning in the National League.”

The Gas House Gang of the 1930s was gone, and Beazley joined a young and hungry Cardinals ballclub in 1942 spring training. Manager Billy Southworth remembered Johnny’s performance the previous year and gave him an opportunity to make the parent club. Beazley earned a spot on the Cardinals’ big league roster and later claimed a slot in the starting rotation after early success in relief.

Just two years after almost bombing out of the minors, Johnny was the top rookie pitcher in the major leagues — and one of the top pitchers, period — during the ’42 season. Compiling an impressive 21-6 record with a 2.13 ERA in 215 1/3 innings, he helped the Cardinals storm past archrival Brooklyn and win the National League pennant during the final days of the season. Beazley’s pitching repertoire included a whistling fastball and a snapping curve; his changeup was mostly off the fastball with an occasional slow curve. He recorded the second-best winning percentage in the league, along with the second-most wins. His 2.13 ERA was also second in the senior circuit; behind teammate Mort Cooper’s leading 1.77. Beazley thanked Southworth for giving him confidence and the chance to pitch, and he credited coach Mike Gonzalez for his turnaround. Apparently Gonzalez had taken a personal interest in the hard-nosed rookie.

Beazley was part of an unflattering incident during the 1942 season. The night before he was to pitch in a key game against the Phillies, he got into an argument with a porter at the train station. Beazley did not want the redcap to carry his travel bag; the porter was African-American, and Beazley reportedly did not like blacks. This was not uncommon, but Johnny’s prejudice may have been less controllable because of the fact that he was commonly known as “Nig” around Nashville after his grandfather stuck him with the nickname when he was about 3 months old. A squabble ensued at the train station, and the porter cursed him. Beazley responded by throwing the bag at him, after which the porter pulled a knife and slashed Beazley on his right thumb. Beazley raised his arm in self-defense, resulting in a deep (but not serious) cut. His Cardinals teammates didn’t know how he would be able to pitch the next day, but Johnny did pitch and carried a 1-0 lead into the ninth before Philadelphia rallied for a 2-1 victory. His teammates knew he was a cocky, hard-nosed player with a terrible temper, and, the temper did not always serve him well.6

Led by Beazley and Cooper on the mound and future Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Enos “Country” Slaughter at the plate, the ’42 Cardinals had an extraordinary 106-48 record for the 1942 season, setting a franchise record for wins that still stands today. In the World Series, Southworth’s Cardinals were matched against the New York Yankees of Joe McCarthy, defending Series champs and winners of five of the previous six fall classics. The Yankees took the opener at St. Louis, and Beazley was dubbed by the Cards to try to even things up at home in Game Two. Before the contest, Johnny satisfied a promise he had made to three of his former Hume-Fogg High baseball teammates. The self-assured hurler had signed a note back in school promising the trio tickets to his first World Series game, and sure enough, the three were at Sportsman’s Park to see his start.

Led by Beazley and Cooper on the mound and future Hall of Famers Stan Musial and Enos “Country” Slaughter at the plate, the ’42 Cardinals had an extraordinary 106-48 record for the 1942 season, setting a franchise record for wins that still stands today. In the World Series, Southworth’s Cardinals were matched against the New York Yankees of Joe McCarthy, defending Series champs and winners of five of the previous six fall classics. The Yankees took the opener at St. Louis, and Beazley was dubbed by the Cards to try to even things up at home in Game Two. Before the contest, Johnny satisfied a promise he had made to three of his former Hume-Fogg High baseball teammates. The self-assured hurler had signed a note back in school promising the trio tickets to his first World Series game, and sure enough, the three were at Sportsman’s Park to see his start.

His guests and the rest of the 34,255 on hand had plenty to cheer about most of the day, as the Cardinals spotted Beazley a two-run lead in the first and added another tally in the seventh. Johnny, meanwhile, held the Yankees scoreless until the top of the eighth, but then New York outfielder Charlie Keller tied the score with a three-run homer off the right-field roof. In the bottom of the frame, Slaughter hit a two-out double and Musial singled him home for a 4-3 lead. Despite surrendering a couple of singles in the top of the ninth, Johnny retired the side and Cardinals fans joyously tossed thousands of seat cushions onto the playing field at game’s end. Afterward, Beazley pulled a lucky brown rabbit’s foot out of his pocket and told gathered reporters that a female fan had given it to him.

A Time magazine writer noted of Beazley after the victory: “He grips the ball so hard his hand quivers for a half hour after each game. But the ‘Beaze’ has plenty on the ball. When Manager Billy Southworth chose the ‘Beaze’ for the second game of the series, even his staunchest admirers feared he would blow up with World Series jitters. The kid was walloped for ten hits, got into one jam after another, but at the last out he was still on the mound, the first rookie to win a Series game since Paul Dean trimmed the Detroit Tigers for St. Louis in 1934.”7

Games Three and Four went to St. Louis, too, as their pitching and hitting dominated the mighty Yankees. They held a three-games-to-one advantage over the Bronx Bombers, and with the title within reach, Southworth gave the ball to Beazley again for Game Five at Yankee Stadium. Leadoff batter Phil Rizzuto homered for New York in the first, but Slaughter tied the score with a homer of his own in the top of the fourth. The Yankees pushed another run across against Beazley in the bottom of the inning, but St. Louis tied it again it in the top of the sixth.

Both Johnny and the Yankees’ Red Ruffing were pitching well, but in the top of the ninth, with Walker Cooper on base, Whitey Kurowski crushed a line-drive home run into Yankee Stadium’s left-field bleachers. St. Louis had a 4-2 lead and New York was down to its final three outs. The first two Yankees up in the ninth reached base on a single and an error, but Joe Gordon was picked off second base by Cards catcher Cooper, and Beazley got the next two on a popup and a groundout to win his second game and clinch the Series.

In the victorious Cardinals’ locker room, Johnny was surrounded by reporters as well as a special guest. Babe Ruth burst into the proceedings and exclaimed, “Where’s that guy that whooped my Yankees?” Shaking the great Bambino’s hand was a cherished Beazley memory that lasted a lifetime.

The World Series hero returned to his native Nashville, where his achievements were celebrated and acknowledged by Mayor Tom Cummings and throngs of fans. They lavished him with gifts and awards; when asked by a reporter what he would do with his $6,100 Series share, the devoted son said he would give it to his mother. For his performance in 1942, the Chicago Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America named Beazley the most valuable rookie of the year. (The “official” Rookie of the Year Award would not be given until 1947.) The Sporting News named him to the All Star Freshman Team along with Stan Musial and Johnny Pesky.

By the time of these honors, Johnny had become Corporal Beazley. In the midst of his whirlwind 1942 season, he had faithfully committed to military service, now that the U.S. was embroiled in World War II. The Army Air Force was waiting for him as the World Series concluded; and after graduating from Officer Candidate School, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in March of 1943.

Lieutenant Beazley was assigned to a morale-boosting unit, and spent much of his time traveling to military bases and playing baseball for the troops. The frequent service games caused an enormous strain on Beazley’s arm. He eventually injured it, which effectively ruined his baseball career.

Beazley’s oldest son, Terry, said his dad would go to a base, pitch two or three innings, then get on a bus and travel 40 miles to the next base without being able to cool down his arm. Cardinals teammate Marty Marion told author Peter Golenbock: “Beazley was in the Army, and we played his Army team in an exhibition game in Memphis. Ol’ Beazley hurt his arm pitching against us. He tried to beat us, I guess. He babied it for a couple of years, and it never did come back.”8

Shortly before he died in 2002, Enos Slaughter shared some reflections on his old teammate. “Johnny Beazley was an excellent pitcher for the Cardinals in his first season,” Slaughter recalled. “He was easy to get along with. He went out and did his job when he was supposed to.”

Still, initial expectations for Beazley were that he could regain his 1942 form when he returned to civilian life and the Cardinals organization after the war. It wasn’t to be. Concerns about his arm and lost velocity first arose early in spring training of 1946, and were justified when the regular season got under way. While he recorded a decent 7-5 record during the year, he made just 18 starts, and his 4.46 earned run average made it clear that the mastery he enjoyed during the ’42 season was history. That magical summer would remain his only great season, and in September Beazley actually announced his intentions to retire at the age of 28. “My arm is all right now, I think,” he told reporters, “but I feel weak and tired and just don’t have any strength anymore, so I’m quitting when the season’s over. I’d quit now, but I don’t want to let [Cards manager Eddie] Dyer down.” Dyer insisted that Johnny stay with the team down the stretch, and although he didn’t pitch again in the regular season, Beazley did appear briefly in the ’46 World Series against the Boston Red Sox — pitching one scoreless frame in Game Five after the Sox had taken a 6-1 lead after seven innings.

St. Louis won the series in seven games, and Dyer got Beazley to change his mind about retiring. He reported to spring training with the Cards in 1947 with new hope that he could regain his prior form, and had a few encouraging, headline-producing outings during the exhibition season. Most experts remained skeptical, but one man who still believed in Johnny was watching with interest. Former Cardinals manager Billy Southworth had moved to the Boston Braves in 1946 after presiding over a dominant St. Louis squad from 1940 to 1945, and immediately led the Boston club to its best season (third place) in nearly 30 years. Beazley had pitched brilliantly for Billy during the ’42 season, and Southworth — ever loyal, perhaps to a fault, to his old players — expected that Johnny would return to his prewar brilliance. He encouraged Braves owner Lou Perini to acquire Beazley, and Perini, anxious to put his own rising club into pennant contention, complied. On April 19, just as the 1947 regular season was getting under way, the Braves purchased the erstwhile ace for an undisclosed sum.

A few weeks later, on May 8, “Beaz” won his first start with the Braves — going the distance in a 12-5 victory over the Pirates that gave Boston a share of first place with the Dodgers. Southworth called Johnny’s possible revival a key to the team’s pennant hopes, but the enthusiasm was short-lived. Beazley won and completed his next start, against Cincinnati a month later, but his arm woes never really subsided. He wound up throwing just 28 2/3 innings the whole ’47 season (2-0, 4.40) and even less in 1948 (0-1, 4.50 in 16 innings of work). Johnny did get to play on his third pennant-winning club when the Braves copped the NL flag in ’48, and no doubt appreciated the bonus money, but it was likely a minor consolation. He appeared in just one game in 1949, retiring all six batters he faced in finishing a game, but his career was over. Southworth’s long comeback chance for his old ace officially ended on May 12, when Beazley was optioned to the minor leagues.

Beazley’s major-league statistics consisted of a six-year record of 31-12 in 76 appearances; along with 147 strikeouts, he finished with a career 3.01 ERA. He attempted to revive his career in 1949 by playing with his hometown Southern Association Nashville Vols, but was unable to overcome his arm injury. Meekly, he recorded a 1-3 record in five games in a Nashville uniform. In 1950, he attempted a comeback by playing for the Dallas Eagles in the Texas League finishing with a 2-2 record. In 1951, he played for the Oklahoma City Indians of the Texas League and finished with a 6-6 record. Finally, he walked off the mound for the last time and retired from baseball. In 1943, Johnny Beazley had married Carolyn Jo Frey of Springfield, Tennessee, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and he now had plenty of time for his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and golf. His post-baseball business career began with the Falstaff Brewing Company of St. Louis, for whom he was general manager of his hometown Nashville branch beginning in 1950. He later purchased the distributorship and ran the company until 1972. His wife died in 1974, but he kept busy by serving on the Metropolitan Nashville Council and as a councilman from 1974 to 1976. He also found a new bride, marrying Jacqueline Spurlock Ezell in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1975. They enjoyed 15 years together until, after being diagnosed with cancer, John Andrew Beazley, Jr. died at his home in Nashville on April 21, 1990. He was 71 years old, and was buried in the Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville.

He was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 1977, and in 2005 was elected to the Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools Sports Hall of Fame. And while the big one, in Cooperstown, will not be opening its doors for him, there are few men there who showed more promise in their rookie years than the hard-nosed Yankee slayer from the Volunteer State.

A version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

The John Andrew Beazley Papers (1916-1990) Manuscript Section, State of Tennessee Library, Nashville.

Nashville sports historian Bill Traughber (including his interview with Terry Beazley)

Golenbock, Peter. The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper, 2001)

Rains, Rob. The St. Louis Cardinals: The 100th Anniversary History (New York: St. Martin’s, 1993)

Websites:

baseball-almanac.com, baseballhistorian.com, baseball-reference.com, cardinalshistory.com, findagrave.com, mlb.com

Nashville Tennessean Archives

New York Times Archives

Time Magazine Archives

The Sporting News

1947Boston Braves Sketchbook

1948 Boston Braves Media Guide

Assorted Associated Press stories, 1942-1947

Thanks to Bob Brady, Bill Francis, and Ray Nemec, and for research assistance from the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1. Farrington, Dick. “Beazley, Cards’ Flashy Freshman,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1942.

2. Ibid.

3. O’Donnell, Red. “It Comes Out — Beazley Was Nashville High ‘Blue Devil,’” The Sporting News, October 15, 1942.

4. Ibid.

5. Farrington, op.cit.

6. Rains, Rob. The St. Louis Cardinals: The 100th Anniversary History (New York: St. Martin’s, 1993), p. 96. A contemporary report is found in the September 13, 1942, New York Times on page S3. Peter Golenbock asked Marty Marion about the incident and was told, “The porter wanted to carry his bag, and Beazley didn’t want him to. Beazley was that sort of guy. [Translation: he didn’t like blacks. All the porters were black.] He was a hard-nosed pitcher. He would knock you down.” Golenbock provided the translation, making Marion’s meaning clear.

7. Time, October 12, 1942.

8. Golenbock, Peter. The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper, 2001), p. 351.

Full Name

John Andrew Beazley

Born

May 25, 1918 at Nashville, TN (USA)

Died

April 21, 1990 at Nashville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.