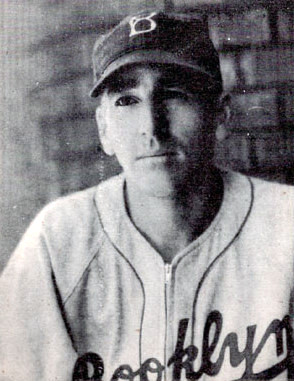

Johnny Hudson

Variously referred to as “The Bryan boy,” “Bryanite,” “Bryan’s contribution to the major leagues,” “Bryan baseball star,” and “Bryan’s gift to the diamond,” John Hudson’s life and family centered around baseball…and Bryan, Texas.

Variously referred to as “The Bryan boy,” “Bryanite,” “Bryan’s contribution to the major leagues,” “Bryan baseball star,” and “Bryan’s gift to the diamond,” John Hudson’s life and family centered around baseball…and Bryan, Texas.

He was born in Bryan on June 30, 1912, and lived there his entire life. He remained there during baseball off-seasons and after his playing career ended until he passed away from cancer in 1970. The house he was born in remains occupied by descendants of the family.

Located in east central Texas, Bryan was a town of about 4,000 residents when Hudson was born. Some 100 years later, its population had grown to just under 70,000, and it had become known as a twin city with College Station, home of Texas A&M University.

Regarding Hudson’s birth, his early baseball cards and newspaper references listed his birth year as either 1914 or 19151 – i.e., two to three years later than 1912. As an example, at the age of 23, a 1936 spring training article from The Sporting News noted that Dodgers’ manager Casey Stengel was considering Hudson for the team “although Johnny was only 21 years old and his experience in professional ball had been limited…”2 Whether this difference in birth years was by accident or on purpose is not known.

Hudson’s parents were natives of North Carolina. His father, William, was born in 1860 in Mooresville; his mother, Annie (née Overcash), was born in 1870. They were married in North Carolina, but before the turn of the 20th century, they moved to Bryan. There William was a carpenter and the four Hudson children were born and raised (Annie never worked outside the home). Johnny was the youngest, following Willie, Joe, and Bertha.

Hudson threw right-handed and batted from the right side. His professional baseball career lasted some 36 years—his entire adult life—as a player, coach, manager, and scout. His major league playing career covered seven years with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Chicago Cubs, and New York Giants, and totaled 426 games with an overall batting average of .242 and four home runs. He was mainly a middle infielder, playing most of those games at second base. At 5’10” and 160 pounds Hudson was not a large man. However, he was given credit as “one of the flashiest fielding infielders in the National League.”3 He was noted to be a “fast, agile fielder, no matter what position he plays.”4 A 1936 article noted that he was a “sturdily built chap, not huge in any sense, but fairly strong.”5

Hudson was commonly called “Johnny” and later on in his baseball career he was referred to by the nickname “Mr. Chips” or “Little Mr. Chips.” The Dodgers’ broadcaster at the time, Red Barber, commonly referred to Hudson using this nickname on his broadcasts. The origin of the nickname is unclear; however, there are numerous references to his ability to come through when the chips were down. One reference noted that he possessed a “pinch-hitting knack that earned him the nickname of ‘Mr. Chips.’”6 At the time of Hudson’s popularity, in 1938-39 with Brooklyn, there was a movie by the title of “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” making the rounds. That might have provided some connection to his nickname as well.

He grew up playing stickball and began building a reputation as a good ballplayer when he was with the local Methodists team in the Bryan Sunday School League. He started out at Bryan High School in 1928 and played baseball there. Hudson’s first publicity was likely a May 1928 column in the Bryan school paper reported that “little Johnnie Hudson has certainly taken care of second base on the baseball team.”7

Bryan High disbanded its baseball team for a few years, which encouraged Hudson to take advantage of a transfer. In 1930 he was offered a baseball scholarship to another nearby school, the Allen Military Academy (AMA), where he also played on the basketball team. There Hudson played three years and was named captain of the 1933 team. Newspaper accounts record that he was regarded by his coaches as one of the best prospects ever developed at AMA. He batted .361 in 1932 and .385 in 1933. During his high school years Hudson played with semi-pro teams in various summer leagues and was a member of the 1931 Navasota team that won the amateur championship of eastern Texas.

Following graduation, Hudson’s coach from Allen Military Academy recommended him for a 1934 tryout with the Houston Buffs (Texas League), which were part of the St. Louis Cardinals chain. For the remainder of the spring he was invited to remain with the Buffs at the club’s training center, Buff Stadium in Houston, Texas. Once spring training ended, Hudson was sent to the Cardinals’ base in Springfield, Missouri. Then, in mid-June 1934, he was signed to a contract to play for Greensboro in the Piedmont League (Class D). He played in nine games with the Trojans, batting .267, but was released in early July and he headed back to Bryan.

Within two weeks he was contacted by the manager from the Jeanerette Blues in the Class D Evangeline League. The Blues were looking for an infielder and Hudson was able to play 30 games for the team before he suffered a bad spike wound that ended his 1934 season. He completed his initial year of professional baseball playing in 39 games with a batting average of .223.

In 1935 Hudson was back with Jeanerette and played in 114 games, batting .295 with 11 home runs. In November 1935, on the recommendation of scout Rudy Hulswitt, he was purchased by the Allentown Brooks with the New York-Pennsylvania League (Class A), part of the Brooklyn Dodgers chain.

Hudson started the 1936 season with Allentown and then was called up to the Dodgers in mid-June. He appeared in his first major league game on Saturday, June 20, 1936 in Ebbets Field against the Chicago Cubs. Hudson played shortstop, batted seventh in the order, and went hitless in three times at bat, with a walk and a run scored. He got his first hit in the second game of a doubleheader on Sunday, June 21, 1936, an RBI single against Lon Warneke. Back in Bryan, 16 of his friends were obviously impressed with Hudson being with the Dodgers and, with a bit of humor tossed in, sent him this Western Union telegram on June 24:

“Dear Johnnie congratulations to you as well as Brooklyn STOP We are all pulling for you down here STOP Stay there and give them all you have STOP If you go back to Allentown dont [sic] report to the Bryan Café hot stove league tis [sic] winter”

He appeared in six games for the Dodgers in what turned out to be a short stint, getting two hits in 12 at bats. By late July he was back with Allentown and finished the 1936 season there, batting .303 in 116 games with 22 triples. However, his play was starting to be noticed; as a result Hudson was able to garner votes for the New York-Pennsylvania League’s MVP award for the 1936 season.

Further, his play in Allentown had impressed Dodgers’ manager Burleigh Grimes and his chances of making the Dodgers’ 1937 roster were looking good. In late January 1937 Hudson received a letter from the Dodgers notifying him to report for training on March at the Fort Harrison Hotel in Clearwater, Florida.8

He had a good spring and came out of spring training as the club’s leader in RBIs. “Regular Job Awaits Hudson” was the headline of one article on March 27, 1937.9 The article mentioned that in 1936 his progress was slowed when the “practice pitchers began throwing curves…He’d aim with due care and swing with firm intent and high hope, but the ball wouldn’t be anywhere near the bat at the time of expected contact.”

Sure enough, Hudson remained with the Dodgers for the start of the season. He was a late inning replacement at shortstop in the second game of the season on April 23. With injuries causing problems for the Dodgers, he was being looked at as a possible regular:

“The practically unheralded Hudson has done his level best to save the situation. Game after game, week after week, he has played grand ball, fielding well, running hard and standing out as the most timely hitter on the club.”10

Eventually Hudson received a mid-April starting assignment at shortstop in a “chilly game in the Brooklyn orchard and impressed the Flatbush fans with his ability and his poise.”11 However, he came down with a bad case of influenza that scuttled his chances as a regular for the season; Woody English took over at second base. He started seven games in late April and early May, but mid-June found him sent down to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association (AA), where he stayed for the remainder of the 1937 season. His playing time was limited in Brooklyn to 13 games and 27 at bats. With Louisville he appeared in 60 games and managed a .292 average.

In preparing for the 1938 season Hudson rejected the initial contract sent to him by Larry MacPhail of the Dodgers. Hudson received a response in late January 1938 thanking him for a “fair presentation of your ideas.”12 This second contract gave him a bit more money if he stayed with the Dodgers…he signed this one.

Over the next three seasons – from 1938 through 1940 – Hudson was a semi-regular with the Dodgers, starting 54% of the Dodgers’ games during that time. His best season was 1938, when he finished 25th in voting for the National League MVP award. That year he hit .261 in 135 games, of which he started 123. The captain and shortstop of the 1938 team was Leo Durocher. Durocher was high on Hudson and said he never saw a second baseman “get as smart as fast as Johnny…Johnny is a born ball player…he has baseball sense.”13

During his 1938 season Hudson played in a memorable game in Ebbets Field. It was on June 15 against the Cincinnati Reds and their pitcher Johnny Vander Meer. Vander Meer had pitched a no-hitter against the Boston Bees on June 11. So, the game on the 15th was featuring a new star pitcher and was receiving a lot of local interest because it was to be the first night game to be played in Brooklyn. There were a number of pre-game activities and the game finally got underway at 9:45 P.M., quite a bit later than normal. There were 38,748 in attendance who witnessed Vander Meer pitch another no-hitter, making it two in a row. Later on in his career Hudson would break up a no-hitter, but this night he just ended up being one of the Dodgers’ seven strikeouts in the game.

The year 1938 was a good one for Hudson in another way, too. While in Brooklyn he met a young bank employee by the name of Vera Ryan. Ryan grew up in the Flatbush area of Brooklyn and was born in Rockaway Beach, New York. They married on November 20, 1938 at the St. Rose of Lima Church in Brooklyn and their honeymoon was an auto trip to Bryan via North Carolina.

Despite his relatively good 1938 season with the Dodgers, the 1938-39 winter found Hudson to be the subject of trade rumors. He had suffered from bad tonsils, and lost 14 pounds by the end of the season. He took care of that problem after the season ended and had the tonsils removed. He gained weight over the winter and was in good playing shape, but was being thought of as more of a utility player for the upcoming season. New manager Leo Durocher was promoting Pete Coscarart as the probable starting second baseman. There were also rumors that the Dodgers wanted to keep Hudson around as a replacement for Durocher at shortstop.

Actually, trade rumors had followed Hudson over the years; as early as 1937, he was said to be “the most attractive trading material the team possessed.14 Manager Bill Terry of the Giants tabbed Hudson as an outstanding young player and had made an offer to the Dodgers in the spring to pick him up.15 In December 1939 Pittsburgh Pirates manager Frankie Frisch was quoted as trying to land him for additional infield depth.16

In any event, Hudson received a 1939 contract that paid him $5,000. He ended the season having played 109 games for the Dodgers, starting in 86 of them, about equally split between second base and shortstop. His batting average slipped a bit to .254.

Although it was not known as such at the time, Hudson played in a historic game in 1939. It did not take place during the regular season, though – it was an exhibition game on April 13. Spring training was winding down and the Dodgers were playing the New York Yankees in Norfolk, Virginia. Hudson played at shortstop in place of Leo Durocher and did not do anything special, going one-for-four in a 14-12 win. However, Lou Gehrig hit his last home run as a professional, even though it did not count in his major league total.

After the 1939 season the trade rumors continued but Hudson was with the Dodgers for the 1940 season and played in 85 games, mostly as shortstop, and batted .218. He took part in another memorable game that year on Thursday, May 30. The Dodgers faced future Giants Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell in the first game of a holiday doubleheader at Ebbets Field, losing 7-0 as Hubbell threw only 81 pitches and faced the minimum 27 batters, allowing only one hit – a single by Hudson, who was subsequently erased on a double play. Hubbell later was quoted as selecting this one game as the finest he ever pitched. He was especially proud that only four balls were hit out of the infield, including the one by Hudson.17 Ironically, in later years Hubbell would become Hudson’s supervisor.

Hudson remained the subject of trade rumors; in the 1940 off-season the Dodgers reportedly rejected offers from the Giants, Cardinals, and Cubs. In early April 1941, at the conclusion of spring training, the Dodgers sold him to their Montreal Royals club (International League). The situation was confusing – here he was seemingly wanted by several big league clubs, yet he got sent down to Montreal. The Dodgers had waivers on Hudson and there was apparent interest in him from the Giants and Tigers. Hudson initially refused to go; however, he changed his mind and was hitting .293 over his first 15 games for the Royals when he received news that he was finally traded.

On May 6, 1941, along with Charlie Gilbert and $65,000,18 he was sent to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for future Hall of Famer Billy Herman. With the Cubs Hudson never got untracked and finished with a batting average of .202 over the course of 50 games. The trade turned out favorably for the Dodgers, as Herman batted .291 over the rest of the season, making the All-Star team and helping the team win the pennant. For years Chicago fans considered the trade to be a “historic Cub blunder.”19

Hudson was not with the Cubs long. He was sold to the Milwaukee Brewers (American Association) on December 23, 1941. He spent the entire 1942 season with the Brewers, playing in 144 games and hitting .225. In a summary at the end of the season, he was given credit for being a “money player” and a “stellar second baseman” whose “brilliant fielding saved more than one game.”20

In mid-May 1943 he signed a contract with the Jersey City Giants (International League) for $650 per month. Horace Stoneham was Jersey City’s President, and a relationship was forged with Stoneham that would continue throughout the remainder of Hudson’s baseball career. He stayed with the Jersey City team through the 1944 season, playing in 172 games and averaging about .220 for Jersey City over the two seasons. Following the end of the season Hudson decided to play winter ball and spent the off season in Cuba with the Cienfuegos team.

In 1945, with his options exhausted, Hudson was brought up by the New York Giants, ostensibly to provide infield utility experience. He spent the year as a reserve, getting into 28 games with only 11 at-bats. His final major league games were on Sunday, September 23, 1945 when he pinch-ran for eventual Hall of Famer Ernie Lombardi in both ends of a double header at the Polo Grounds. He scored a run in his last appearance as a pinch runner, a 7-3 loss to the Boston Braves. He was released in November 1945.

For a time he thought about playing the 1946 season with the Nashville Volunteers (Southern Association). However, Carl Hubbell, now head of the Giants’ farm system, tabbed Hudson to manage the organization’s team in Jacksonville, Florida.

Over the next three years, 1946-48, Hudson was player-manager for the Jacksonville Tars of the South Atlantic League (Sally) League, Class A. He was an active player, averaging 106 games per year with an overall batting average of .257. As manager, he was given credit for a “magnificent job with under-par material.”21

Well-liked in Jacksonville, he received gifts from Tars’ fans at a September game in 1946.22 In his last season with the club, 1948, a “Johnny Hudson Night” was held and he “received a wheelbarrow of gifts and a cash purse” from fans.23 The cash amounted to $132.14 from the white fans, “…plus an unannounced sum that was donated by colored followers of the club.”24 Among his gifts was a live pig which was greased and managed to escape Hudson’s hold.

After leaving Jacksonville, from January 1949 until his death in 1970, Hudson served as a scout for the Giants. His most notable signing was Mike Phillips, a Texan who was picked 18th overall in the first round by San Francisco in the June 1969 amateur draft. Phillips had an 11-year career in the majors, playing 712 games.

Another signee was Ed Feldman from College Station, Texas, who was signed in 1960 at the age of 18. Feldman reveres Hudson and still refers to him as “Mr. Hudson.” He said that Hudson was a “genuine good man who was more like a father to me.” Interestingly, Feldman, who knew of Hudson as a kid in Little League in the Bryan-College Station area, never knew much of his major league career. While Feldman had arm problems and did not make it to the big leagues, he was successful in law enforcement as the Police Chief in College Station.

Over the years Hudson also was the Giants’ special coach for infielders, helping players such as Jim Ray Hart and Hal Lanier. He was active for many years in overseeing training camps and tryout camps held throughout Texas. He served as a coach for the Giants in the Arizona Fall Instructional League from 1960 through 1966. When he found time, Hudson also was an assistant golf pro during his off-seasons, and golf remained a favorite activity after his playing days were over.

Hudson loved baseball and loved being a scout. He was President of the South Plains Professional Baseball Scouts Association (SPPBSA), comprising nine states.25 When asked about the life of being a scout, Hudson noted that “it’s not so bad in the daytime…but you do sort of get an all-alone feeling in some towns after a night game when you don’t know anyone you can talk to about baseball.”26

Hudson died in his home town of Bryan, on November 7, 1970, and is buried in City Cemetery there.

Following his death Hudson received several tributes. One was the “Johnny Hudson Memorial Award” created to recognize an outstanding high school coach from the region. Another was offered by writer Clark Nealon in The Houston Post: “Of the many baseball scouts we’ve known, we rate none ahead of Johnny for genuine interest in the welfare of the young ball player, whether he signed him or not, or for consistent thoughtfulness.”27 In 1999 Hudson was ranked #18 on a list of the Brazos Valley’s 20 greatest athletes of the 20th century.28

Johnny and Vera Hudson had three children: John Jr., David, and Diane. John Jr. played baseball at Texas A&M and was on the same team with future All-Star major leaguer Davey Johnson. According to John Jr., his father would not sign Davey because he wanted him to stay in school one more year. David went to Texas Tech University, is married to Robbie, and resides in Lakeway, Texas. Daughter Diane and husband Don Wheat live in Benbrook, a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas. John Jr. and wife Beverly share time between Sugarland, Texas, and Pagosa Springs, Colorado.

Other than working as a postal carrier and being an assistant golf pro during several off-seasons, baseball was the only job Hudson knew. In addition to playing against and working under Carl Hubbell, he was on teams with some well-known managers – Casey Stengel (1936), Burleigh Grimes (1937-38), Leo Durocher (1939-40), Jimmie Wilson (1941), Charlie Grimm (1942), Gabby Hartnett (1943-44) and Mel Ott (1945). He also shared “the pine” with Babe Ruth, who was a coach for the 1938 Dodgers, and was a regular golfing partner with Willie Mays.

For nearly 40 years – from the early 1930s until 1970 – Johnny Hudson was indeed Bryan’s gift to baseball…and baseball’s gift to Bryan.

Sources

The preparation of this biography was greatly aided by interviews with John Hudson, Jr. He also made available a copy of a large family scrapbook of 127 pages along with personal papers. While the scrapbook had a significant amount of material, almost all of the articles had the date and name of the newspaper trimmed. In addition, The Sporting News collection, available through the Society for American Baseball Research, provided substantial historical information on Hudson’s baseball career.

1 The 1939 Play Ball card #154 showd his birth year as 1915; the 1940 Play Ball card #147 listed it as 1914; a 1999 article in The Press (Bryan, Texas) cited it as 1914.

2 Tommy Holmes, “Hudson Satisfies Stengel as a Starting Shortstop,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1936, 1.

3 GUM, Inc., 1939 Play Ball card #154.

4 GUM, Inc., 1940 Play Ball card #147.

5 Holmes, “Hudson Satisfies Stengel As a Starting Shortstop”

6 Hy Turkin, “Hudson to Hustle with Royals for Dodger Comeback,” undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

7 Milton R. Maloney, “Goalines,” undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

8 Letter to John W. Hudson from John Gorman, Business Manager, Brooklyn National League Baseball Club, January 29, 1937.

9 Charles E. Parker, “Regular Job Awaits Hudson, Impressive Work at Short Heading Youngster for Starting Berth with Dodgers,” New York World-Telegram, March 27, 1937.

10 Tommy Holmes, “Jinx Digs New Hole in Brooklyn Infield, The Sporting News, April 15, 1937, 3.

11 Tommy Holmes, “Grimes Goes 50-50 in Dodgers Forecast,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1937, 2.

12 Letter to John Hudson, from Lawrence MacPhail, Vice President, Brooklyn National League Baseball Club, January 29, 1938.

13 James Cannon, “Durocher Sees Hudson, Star at 2nd, .300 Hitter,” New York Journal-American, August 23, 1938.

14 Tommy Holmes, “Leo Seeks Second Wind in the West,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1939, 6.

15 McCullough, “Dodger Data,” undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

16 “Old Injury to Young First Fret of Frisch,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1939, 5.

17 “His Finest Game,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1954.

18 There were various figures reported over the years, ranging as high as $65,000.

19 Frederick G. Lieb, “Inside of Game’s Most Famous Deals, Herman’s Trade to Dodgers in 1941 Historic Cub Blunder,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1946, 13.

20 R.G. Lynch, “Maybe I’m Wrong,” undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

21 “Macon Peaches Here for Last Time; Sheldon Jones Will Hurl,” undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

22 The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 27.

23 The Sporting News, September 1, 1948, 31.

24 Arnold Finnefrock, “Mario Picone Blanks Macon Team, 5 to 0, Hudson Is Showered With Gifts; Columbus Cardinals Play Here Tonight,” Jacksonville Times-Union, undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

25 Harold Scherwitz, “Coaches and Scouts Learn at Clinic,” The Sporting News, February 26, 1972, 47.

26 Arnold Finnefrock, “Fanning with Finney,” Jacksonville Times-Union, undated news article from Hudson scrapbook.

27 Clark Nealon, “Couple of 49ers are familiar here,” The Houston Post, November 13, 1970, 57.

28 Greg Huchingson, “Huch’s Huddle,” The Press (Bryan, Texas), September 2, 1999, 2.

Full Name

John Wilson Hudson

Born

June 30, 1912 at Bryan, TX (USA)

Died

November 7, 1970 at Bryan, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.