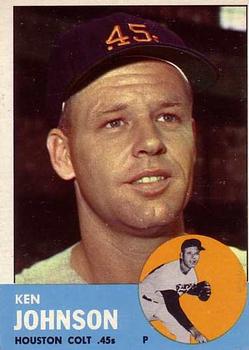

Ken Johnson

Early in 1966, when it was still unclear whether the Braves would take root in Atlanta or return to Milwaukee because of a pending court ruling, Ken Johnson was not worried. “If we have to go back to Milwaukee, it will be all right with me,” Johnson said. “I liked it there. I like anyplace in the big leagues where I’m pitching.”1

Early in 1966, when it was still unclear whether the Braves would take root in Atlanta or return to Milwaukee because of a pending court ruling, Ken Johnson was not worried. “If we have to go back to Milwaukee, it will be all right with me,” Johnson said. “I liked it there. I like anyplace in the big leagues where I’m pitching.”1

Born on June 16, 1933, Kenneth Travis Johnson grew up in West Palm Beach, Florida, the son of Ernest and Margie Johnson. His father was a bank teller. Johnson’s brother, Ernest Jr., also called “Buddy,” worked for the Pratt & Whitney aircraft plant before retirement. A sister, Shirley, died of breast cancer at age 45. Johnson was actually born left-handed but his father, out of habit, put Ken’s baseball glove on his left hand and taught him to throw right-handed. Johnson eats and writes as a lefty but pitched professional baseball right-handed for 19 seasons. He played baseball at Palm Beach High School, where the coaches said, “If you’re a serious baseball player, don’t play any other sport.” Like many high-school players, Johnson played American Legion baseball in the summer.2 At age 18, he was a professional. At 32 he was a 16-game winner in the major leagues.

Johnson took a long road to the major leagues. In 1952 he reported to spring training in his hometown of West Palm Beach, Florida (where he had been a scoreboard boy), as an 18-year-old pitching prospect for the Philadelphia Athletics. He won 14 games for the Class A Savannah (Georgia) Indians of the South Atlantic League. Before joining the Army, Johnson pitched an 18-0 shutout against Charleston.3 Back from the service in 1956, Johnson won 12 games for the Columbia (South Carolina) Gems, also of the South Atlantic League. Johnson started 30 games for the Little Rock Travelers of the Double-A Southern Association in 1957 and had 30 starts and 12 relief outings for the Buffalo Bisons of the Triple-A International League in 1958 before making his major-league debut for the Kansas City Athletics on September 13. Johnson gave up a second-inning grand slam to Washington Senators catcher Clint Courtney in a relief role. He made one more relief appearance against the Chicago White Sox and returned to the minors in 1959.

Johnson won 16 games for the Portland Beavers of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League with five shutouts and a 2.82 ERA. Called up late in the season, he lost his first major-league decision to Detroit’s Jim Bunning at Briggs Stadium on September 22. Johnson lasted four innings and gave up a three-run home run to Harvey Kuenn. Four days later Johnson earned his first win in a start at Cleveland. Used mostly as a reliever in 1960, Johnson won his fifth game when the A’s were 40 games under .500 and hurting at the gate, too.

By 1961, the Athletics had given up on Johnson, who had learned to throw a knuckleball pitching winter ball in Puerto Rico. When Dick Schofield homered off Johnson on a knuckler in spring training, manager Joe Gordon told him to stop throwing it. By May 6, Johnson was 0-4 with a 10.61 ERA and the Athletics sold him to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League, where he posted a 5-5 mark. In what Johnson later called the “biggest break of my career,” he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds on July 21 for pitcher Orlando Pena and cash. Johnson joined the Reds immediately and helped them win the National League pennant with a 6-2 record and 3.25 ERA in 83 innings, three complete games in 11 starts, and one save.4 Johnson won his first two starts, beat Mike McCormick, Bob Gibson, and Don Drysdale in August, and shut out the Phillies on September 4. The Reds won 14 of 22 games at the end of the regular season to win the pennant by four games over the Los Angeles Dodgers. In the World Series, which the Reds lost to the Yankees in five games, Johnson retired both batters he faced in former Kansas City teammate Bud Daley’s Series-clinching victory for New York. (Roger Maris and Hector Lopez had played with Johnson, too.) Johnson looked forward to a full season with the National League champions in 1962.

Instead, the Houston Colt .45s selected him 29th in the National League expansion draft. The move reunited Johnson with Harry Craft, the Colt .45s’ inaugural manager and Johnson’s first skipper in Kansas City. Johnson took his new situation in stride, saying he would have had a tough time making the Reds’ staff with prospects Ken Hunt and Jim Maloney joining an experienced group of starters. Johnson started throwing his knuckleball again, saying it made his other pitches more effective. Once, St. Louis third baseman Ken Boyer asked Johnson why he didn’t throw his knuckler anymore. “The next time I faced him, I struck him out with the knuckler,” Johnson said. Pitching for San Juan in the Puerto Rican League, Johnson fanned Giants slugger Orlando Cepeda twice on knuckleballs, pitched two 1-0 games and had a 4-2 record.

At the Colt .45s’ spring-training camp at Apache Junction, Arizona, Johnson won two starts against the Los Angeles Angels, as Houston won the Cactus League. Craft named Johnson his second starter. In his first four starts, Johnson allowed nine earned runs in 29 innings but lost each game. His record was 0-5 when he won his first game on May 18 with a 10th-inning single after allowing a Willie McCovey tape-measure homer in the bottom of the ninth that tied the score, 2-2. Five days later Johnson became the first pitcher to beat Bob Purkey, who would go 23-5 for Cincinnati in 1962, with a 2-0 shutout. On June 3 Pittsburgh’s Bob Skinner drove a Johnson delivery onto the right-field roof of Forbes Field, becoming only the fifth player to reach such heights, but Johnson had a respectable 4-7 record and 3.00 ERA through June 17.

Johnson objected to sportswriters calling him a hard-luck pitcher: “If people call me that long enough, that’s what I’ll become.” But he had his share of hard luck during the season.5 On September 12 Johnson stopped Maury Wills’ 19-game hitting streak but lost his 15th game (against six wins), 1-0, at Colt Stadium on Frank Howard’s fifth-inning home run. Until then, Johnson had not allowed a baserunner. There were some positive highlights as well that season. On August 14 against St. Louis, Johnson struck out 12 Cardinals batters, tying Turk Farrell for the club’s single-game strikeout record. On September 18 Johnson’s three sacrifice bunts along with an RBI helped beat Casey Stengel’s “Amazin’ Mets” for his seventh victory. Johnson (7-16) had a respectable 3.84 ERA and led the National League in strikeout/walk ratio with 178 strikeouts and 46 walks in 197 innings for an eighth-place team. The Colt .45s became the second franchise in major-league history with a pitching staff that recorded 1,000 strikeouts, and the club awarded each pitcher, including Johnson, a 14-karat-gold tie clasp with the engraving “1,000 Ks” at a pregame ceremony in August 1963.6

Johnson won 11 and lost 17 with a 2.65 ERA in 1963 for a ninth-place club that never reached the .500 mark. On April 17 he started against the San Francisco Giants and pitched 12 innings for a 2-1 victory as the .45s scored the deciding run in the top of the 13th. On April 27 Johnson lost 1-0 to the Cincinnati Reds when Frank Robinson was awarded first base when rookie catcher John Bateman was called for interference after bumping into Robinson at the plate, and then scored on Johnny Edwards’s single.7 On July 15 at the Polo Grounds, the Mets’ Carlton Willey hit a grand slam off Johnson, becoming the first Mets pitcher ever to hit a bases-loaded homer.8 After a 3-2 complete-game loss to Bob Gibson and the Cardinals on August 14, and a 1-0 loss to Cincinnati’s Joe Nuxhall on August 20, Johnson had a 6-17 record but won his last five decisions to end the season. On Opening Day 1964 in Cincinnati, Johnson became the first pitcher to put Houston in first place. He beat the Reds’ Jim Maloney, 6-3, but it was a solemn occasion. Houston players wore black armbands in memory of Johnson’s best friend and road roommate, pitcher Jim Umbricht, who had died of cancer five days earlier at the age of 33. Johnson dedicated the game to Umbricht. “I thought about him before the game,” Johnson said. “All the fellows did.” In his next start, Johnson beat another ace, Milwaukee’s Tony Cloninger, one of four different Braves starters Johnson defeated that season.

Johnson’s third start of 1964 was normally good enough to beat anyone. On April 23 he no-hit the Reds but lost, 1-0, when second baseman Nellie Fox’s ninth-inning error scored Pete Rose, who had tried to bunt to break up the no-hitter and reached on Johnson’s own throwing error. Johnson even suffered a bruised shin when Chico Ruiz hit a line drive to the mound in the ninth inning that turned into an out. “It’s amazing,” he said the next day, “how many people come up to me and start their sentences off the same way: ‘Congratulations, Ken. That was sure a lousy break.’ See what I mean? They give me congratulations and condolences at the same time. They don’t know whether to feel glad or sad for me.”9 The 10th no-hit loss in major-league history got Johnson a guest appearance on the popular CBS I’ve Got a Secret game show four nights later. (Baseball buff Henry Morgan guessed Johnson’s secret, that he had pitched a no-hitter and lost.)10

Johnson’s lack of hitting support even drew the interest of a Mexican voodoo practitioner who had called the Colt .45s’ Spanish-language radio announcer, Rene Cardenas, claiming that he could cast a good-luck spell on Johnson if he could obtain one of Johnson’s old baseball gloves.11

During the second game of a twi-night doubleheader on May 23, Johnson fired a five-hit, 4-0 shutout against the Mets in a game that did not start until 11P.M. due to several rain delays.

“We could have had him but I thought he was a seven-inning pitcher and now I see I’m right,” said Casey Stengel. “After seven innings, he gives up a hit.”12 Johnson had lost his next two starts after the April 23 no-hitter and later lost two 1-0 games and another, 2-1. On July 18 he finally won a close one with some medical help. During a start at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, Johnson complained, “Every time the wind blows out on the mound, it feels like somebody is holding an ice cube against my back.” Trainer Jim Ewell applied a thick coating of oil to Johnson’s back between the fifth and sixth innings and Johnson won, 2-1.13 In 11 of his 16 losses in 1964, Houston was either shut out or managed just a single tally.

The Braves must have remembered what Johnson had done against them when they traded outfielder Lee Maye for him and first baseman-outfielder Jim Beauchamp on May 23, 1965. The Colt .45s had become the Astros and were playing in the Harris County Domed Stadium, better known as the Houston Astrodome. Johnson had a 3-2 record for the Astros when he left for Milwaukee and had his first winning season for a lame-duck team that would move to Atlanta in 1966. Milwaukee had winning records at home and on the road, led the loop in home runs, and contended until early September, but the impending move kept fans away. The Braves drew just over 555,000 fans, last in the league. Johnson won 13 and lost 8 as the Braves’ third starting pitcher and finished 16-10 overall. He beat the powerful Cincinnati Reds three times and the Pittsburgh Pirates twice, but lost twice to the Phillies’ Ray Culp and twice to the eighth-place Cubs.Johnson’s wife, Lynn, recalled a family atmosphere in Milwaukee where wives got together for coffee and went to the games. The move to Atlanta was heavy on the minds of Milwaukee residents. “The Braves were leaving and the people there were upset about it,” Lynn Johnson said. “They didn’t do a lot of booing.”14

Relocating to Atlanta meant the Johnsons would live closer to family. Mrs. Johnson’s parents lived in Augusta, Georgia. “The wives would get apartments in the same complex,” she added. “When the players went on the road, the wives would plan things to do together.”15

On April 8, 1966, Johnson pitched the opening game of a three-game preseason exhibition series in Atlanta Stadium against the Yankees. In the second regular-season game, Johnson lasted just three innings and lost, 6-0, to the Pirates on Willie Stargell’s two-run homer and RBI single. Three days later, Johnson was among 11 Braves fined for fraternizing with opposing players before a game with the Mets. On May 18 Johnson stopped Vernon Law’s personal 10-game winning streak that stretched over two seasons. Johnson was the last to beat Law, on July 15, 1965.16

For the next month, Johnson struggled with tendinitis in his right shoulder but returned to beat the Pirates on June 10. Two weeks later, he ended the Braves’ five-game losing streak, beating the Dodgers, 5-4, in the day half of a day-night twin bill at Dodger Stadium that drew 79,289 paid customers. Johnson went the distance, hit a home run, and had a 6-5 record. Manager Bobby Bragan said, “When Johnson goes out there, you know you’re going to be in the game.” Johnson replied, “Plenty of guys have more ability than I do. But I’ve worked hard to get where I am. I’ve put in plenty of long hours.”17

In 1967 the Braves embraced the knuckleball, moving Phil Niekro into a starting role with Johnson and reacquiring catcher Bob Uecker to catch the dazzling deliveries. Niekro led the NL in earned-run average and Johnson won 13 games. The “Year of the Pitcher” in 1968 was not a good one for Johnson, who dropped to 5-8 on a .500 team on which he was reunited with former Houston manager Lum Harris. On May 10 Johnson was the winning pitcher and tossed a complete game in a 2-1 Braves victory in Atlanta over Los Angeles Dodgers’ ace Don Drysdale, who proceeded to pitch a then-record 58⅔ scoreless innings and six shutouts over his next seven starts. The Braves won the NL West Division and faced the Eastern Division champion New York Mets in the 1969 NLCS, but Johnson was not there. The Braves sold him to the Yankees on June 10, but he was with them only two months before the Cubs bought him on August 11 as extra bullpen help for their NL East Division championship drive. Johnson had a 1-2 record in nine games including eight relief appearances. He was on the mound on September 7 when Don Kessinger’s error and Richie Hebner’s single produced two unearned runs in the 11th inning as the Cubs lost in extra innings to the Pirates at Wrigley Field before going on the road and free-falling out of first place. “It was fun until they started losing,” Lynn Johnson remembered. Released by the Cubs in April 1970, Johnson pitched briefly for the Montreal Expos, his second expansion team, and pitched his last game on April 18, 1970.18

After his baseball career ended, Johnson returned to West Palm Beach and supervised the Work Ship program at Palm Beach Atlantic College. He found work sites for students to get real-world experience for a certain number of hours that the college required for graduation. Some of the assignments involved assisting those with disabilities, Lynn Johnson said. After that, Johnson coached baseball at Louisiana College in Pineville, where his son, Kenneth Travis Johnson Jr., got a baseball scholarship and later became a family practice physician. Another son, Russell “Rusty” Johnson, became a certified public accountant, while daughter Janet taught kindergarten in Alexandria, just across the Red River from Pineville, where the Johnsons lived in 2014. A grandson, Jason Johnson, a pediatric cardiologist in Memphis, lost an 11-month-old son to a severe heart condition. All three graduated from Louisiana Baptist College, where Ken had been assistant baseball coach for 10 years before retiring. “We babysat grandchildren so that the wives could work,” Lynn Johnson said.19

On November 21, 2015, Johnson passed away at the age of 82 at his home in Pineville, Louisiana. His son, Kenneth, Jr., said that his father had been bedridden with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and that he died after contracting a kidney infection.20 Most of Johnson’s baseball experiences in recent years remained lost or clouded in his mind and he was unable to share them for purposes of this article because of Alzheimer’s disease, which Lynn said he inherited from his father. In a brief conversation in the summer of 2014, Johnson did express appreciation to the author that an article would be published on his career, also intimating that Rose may have beaten out the play that was called an error.

Sadly, the New York Times online obituary is titled, “Ken Johnson, Only Loser of 9-Inning No-Hitter, Dies at 82.”21 His accomplishments thus deserve more attention, especially considering a professional baseball career that began at age 18, included 13 big-league seasons, and finally ended in 1970. How many ballplayers can say they started out with Connie Mack, pitched for two expansion teams and two jilted franchises, appeared in a World Series, threw a no-hitter, were part of a controversial franchise shift and a memorable collapse – and still coached his son in baseball and was able to enjoy six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren? The grand-kids got a big charge out of reading about Grandpa on the Internet, sitting on his lap as they did it. That is another memory Johnson shared and was able to take with him.

An updated version of this biography appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Bob Wolf, “Milwaukee Just ‘Two-Bit Town,’ Bragan Spouts After Decision,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1966: 6.

2 Lynn Johnson, telephone interview, December 12, 2013 (Lynn Johnson interview).

3 “Sally League Class A,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1953: 32.

4 Clark Nealon, “Vet Server Johnson Shoots for No. 1 Job on Colts’ Hill Corps,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1962: 29.

5 Mickey Herskowitz, “‘They’ll Talk About It for 30 Years,’ Says Loser Johnson,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1964: 5.

6 “Colt 45s,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1963: 18.

7 Major Flashes, “Interference Call Costly,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1963: 27.

8 “Willey Slams Historic Blow,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1963: 21.

9 The Sporting News, May 9, 1964.

10 Lynn Johnson interview; imdb.com/title/tt1212755/, accessed December 12, 2013; Mickey Herskowitz, “Woody Warns Hill Fraternity – ‘The Hitters Are Out to Get Us,’” The Sporting News, May 16, 1964: 13.

11 Mickey Herskowitz, “Colts Fire Salutes to Johnson’s Start,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1964: 25.

12 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1964: 18. Not surprisingly, Casey’s quote is somewhat misleading; Johnson actually gave up two hits in the second inning of that contest.

13 “Oiled Back Helps Johnson,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1964: 25.

14 Lynn Johnson interview.

15 Lynn Johnson interview.

16 “Johnson Deals Law His Only Two Losses Since July ’65,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1966: 15; “National League,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1966: 22.

17 Wayne Minshew, “Johnson Rare Jewel – Steady Teepee Hurler,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1966: 8.

18 Lynn Johnson interview.

19 Lynn Johnson interview.

20 Bruce Weber, “Ken Johnson, Only Loser of 9-Inning No-Hitter, Dies at 82,” New York Times. Obituary. November 23, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/24/sports/baseball/ken-johnson-82-only-loser-of-9-inning-no-hitter-dies.html?_r=1. Accessed November 25, 2015.

21 Ibid.

Full Name

Kenneth Travis Johnson

Born

June 16, 1933 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

Died

November 21, 2015 at Pineville, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.