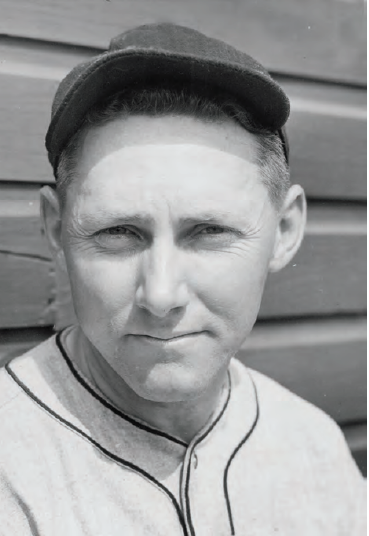

Kiddo Davis

If the fates had been kinder to George “Kiddo” Davis, he would have had the opportunity to display his skills in five World Series during his eight major-league seasons.

In two Series with the New York Giants, 1933 and 1936, the center fielder complemented his outstanding defensive work with 8 hits in 21 at-bats, a robust .381 average — or 99 percentage points above his career regular-season average.

Davis also played for the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals and the 1937 Giants, both of whom went on to win National League pennants, and as a 24-year-old rookie he made one appearance with the pennant-bound 1926 New York Yankees. A winning ballplayer? One would say yes.

George Willis “Kiddo” Davis was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on February 12, 1902, the youngest of eight children of George E. and Bessie E. James Davis. All of his siblings were born in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, where George’s father worked in the coal mines, as did his father before him in Wales. His father’s new and far less dangerous job, as a brakeman on the New Haven Railroad, prompted the family’s move to the industrial city in southern Connecticut.

George was just a boy when he acquired the nickname that would forever be his trademark. As his son, 82-year-old George Jr., recalled in 2013: “He told me that when he was 9 or 10 years old, he was always playing with kids 11, 12, 13. When they’d choose up sides, they’d say, ‘I’ll take the kiddo.’ ”

George’s mother died of Bright’s disease when he was just 15, and his aunt, Edna Mary Waters, “kind of took over and watched over him,” according to his 90-year-old niece, Edna Miller.

At Bridgeport High School, Kiddo quickly developed into a star third baseman and, as a sophomore sparked coach Fred Hunt’s Hilltoppers to the 1918 state championship. The spring season was climaxed by Bridgeport’s 3-2 victory over Evander Childs High School of New York City, a game billed as the Eastern championship. Bridgeport High captured the state title the next season as well.

For reasons lost in time, Davis left school in 1920 and went to work for a local biscuit company. Realizing that he would require a high-school diploma to obtain a college athletic scholarship, he met with Bridgeport High’s principal and was allowed to re-enter the school. Because of his age, though, he was ineligible for baseball and worked part-time as a bookkeeper after school hours.

Eddie Reilly, the high school’s three-sport coach, was well aware of Davis’s baseball skills; he had coached the youngster in semipro competition. So he was able to place Davis in the lineup when Bridgeport High played a prep school or college freshman team.

Bill McCarthy, New York University’s well-respected varsity coach, was an interested spectator on the day when Bridgeport High traveled to Manhattan and defeated the Violet freshmen, 6-5. Davis led the way defensively and at the plate with a 4-for-5 performance, including a home run. A baseball scholarship to NYU soon followed.

Davis went on to earn a bachelor’s degree, with honors, in business administration. He also earned considerable accolades for his play on the baseball field, batting over .500 with the freshman squad and .501 and .486 as a member of the Violet varsity. As a senior he assembled a robust collection of extra-base hits (six home runs, seven triples, six doubles), and twice hit a pair of homers in a game.

The Yankees, mindful of other metropolitan colleges’ contributions to the big leagues — Columbia sent Lou Gehrig to the Yankees and Eddie Collins to the Philadelphia Athletics; Fordham sent Frank Frisch to the Giants — took note of Davis’s productivity at NYU, and scout Paul Krichell, who gained lasting fame for discovering Gehrig at Columbia, signed Davis to a Yankees contract after the Violets’ season ended.

The Yankees team that Davis joined in June of 1926 was a powerhouse, featuring no fewer than seven future Hall of Famers: right fielder Babe Ruth, first baseman Lou Gehrig, center fielder Earle Combs, second baseman Tony Lazzeri, pitchers Waite Hoyt and Herb Pennock, and manager Miller Huggins. The left fielder, Bob Meusel, was a career .309 hitter who had led the American League with 33 home runs and 138 runs batted in the previous season. The 1926 club would win the first of three straight American League pennants.

Davis accompanied New York on a two-week Western trip, but he got into only one game. At Cleveland’s Dunn Field, on June 5, he replaced Ruth in the bottom of the eighth inning in a game won by the Indians 15-3. The Babe had driven in all of the Yankees’ runs, two coming on his 19th home run of the season. Davis recorded no putouts nor did he get an at-bat on that Saturday afternoon as he became the first NYU alumnus to play in the big leagues.

Shortly thereafter, Davis was optioned to Newark of the International League, where he played regularly in the second half of the season and finished with a .290 batting average in 78 games.

On December 18, 1926, Davis married his high-school sweetheart, Myrtle Prout, the daughter of a former Bridgeport police captain. Four years later they became the parents of George Jr.

On the baseball front, this was the beginning of a frustrating five-year period for Kiddo Davis. He distinguished himself at minor-league waystops yet was unable to return to the majors. In 1927 he failed to hit well with Nashville of the Southern Association (.220) and Reading of the International League (.267), and was shipped to Hartford of the Eastern League. Playing center field for the Senators, he won the EL batting title with a .349 average. Presto. His contract was sold to St. Paul of the American Association.

Davis, who stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 178 pounds, developed into a star during the next four summers with the Double-A Saints, hitting above .300 each year (.310, .315, .366, .343) and fielding superbly. In the latter season he reached career highs in hits (214), runs scored (134), home runs (26), triples (15), total bases (358), and stolen bases (24). Finally, the Philadelphia Phillies took notice and purchased his contract.

The 1932 Phillies, managed by Burt Shotton, proved surprisingly competitive, finishing in fourth place — their highest finish in 15 years — with a 78-76 record. Davis was a perfect complement to sluggers Chuck Klein (.348, 38 homers, 137 RBIs), Don Hurst (.339, 24 homers, 143 RBIs) and Pinky Whitney (.298, 13 homers, 124 RBIs).

As a 30-year-old rookie, Davis put forth the finest of his eight major-league seasons. After a slow start, he wound up batting a career-best .309, amassed 178 hits, including 39 doubles, scored 100 runs and drove in 57. His 16 stolen bases placed fifth in the league.

Davis hit the first of his 19 home runs off Brooklyn Dodgers relief pitcher Fred Heimach, a left-hander, at Baker Bowl on April 29, 1932. The Phillies won handily, 13-6.

In the field Davis ranked second among National League outfielders in putouts (411) and fourth in assists (15), and tied with Cincinnati’s Babe Herman with six double plays. Veteran writers were labeling him the Phils’ finest center fielder since Dode Paskert, who starred on the club’s 1915 pennant winner.

On December 15, 1932, Davis was stunned to learn that he was a key component in a three-club, five-player deal that sent him to the Giants. New York parted with veteran outfielder Fred Lindstrom, who went to the Pittsburgh Pirates, and outfielder Chick Fullis, who became Phillies property.

The Giants’ new manager, first baseman Bill Terry, was delighted to have Davis’s defensive skills in center field; he was second among league outfielders with a .988 percentage. And although he batted just .258 (augmented by a personal-best seven homers) for the season, he was considered an important contributor as the club won the 1933 pennant.

The Chicago Cubs trailed the Giants by just 5½ games on September 15 when New York arrived in Wrigley Field for a four-game series. With superb pitching from Hal Schumacher and Hi Bell, the latter working in relief of Roy Parmelee, the Giants swept the pair, 5-1 and 4-0.

In the opener Davis contributed a pair of hits and a run scored in four at-bats before being ejected for decking Cubs reliever Pat Malone, a husky 200-pounder, in a fight in the eighth inning.

The disturbance had its genesis in the fourth inning when Malone’s high hard one sailed too close to Davis’s head. “Davis yelled that he would come out after Pat if he sent up another bean ball,” reported the next day’s New York Sun. “Davis then singled, and he got another single in the sixth, and this incensed Malone, and he said he would take a punch at Davis the next chance he got.

“In the eighth Davis grounded out to Bill Herman and Malone swaggered over to the first-base line as Davis ran for the bag. ‘Well, I got you that time,’ said Pat, ‘and I’ll get you again, and right now.’ And with that Malone threw down his glove at Davis’ feet and swung a right that just grazed Davis’ face. Davis feinted with his right and cleverly crossed his left to the button.”

Two stitches were needed to close the cut on Malone’s chin. Said Giants pitcher Fred Fitzsimmons: “I could hear Malone’s teeth rattle where I was sitting in the dugout.”1

New York Times columnist John Kieran, in praising Terry’s managerial expertise, wrote: “Just what particular charm he used on Hughey Critz, George Davis or Joe Moore is still a mystery, but it brought results. If a great stop was needed to save the day, one of them would make it. If a hit was required to win a ball game, the weakest hitter on a weak-hitting team would rap a rousing blow to safe territory.”2

In the Giants’ World Series victory over the Washington Senators in five games, Davis elevated his batting to all-star level. Hitting safely in each of the five games, the 31-year-old center fielder went 7-for-19 at the plate, a .368 average. He outhit all of his better-known teammates save Mel Ott, who checked in with a .389 average (7-for-18) Terry, a lifetime .341 hitter, batted just .273 in the Series.

Davis appeared in another World Series with the Giants, in 1936, but not before he wore the uniform of two other teams. Seeking better hitting in 1934, the world champs dispatched him to the Cardinals for another outfielder, George Watkins, just as spring training was winding down.

Davis got off to a .303 start as a part-time outfielder with the Redbirds, the rollicking bunch known as the Gas House Gang. With Dizzy Dean, Joe Medwick, Pepper Martin, Rip Collins, Leo Durocher, and player-manager Frankie Frisch, among others, St. Louis was stocked with colorful, outspoken characters who played hard and well. They nosed out the Giants by two games for the pennant and defeated the Detroit Tigers in the World Series.

With an outfield of Medwick, Jack Rothrock, and Ernie Orsatti, though, Davis was deemed expendable and, on June 15, he was traded back to the Phillies for Chick Fullis. He played in 100 games for the seventh-place Phils and batted .293. For the second straight year, Davis ranked second among league outfielders with a .988 fielding percentage.

Bill Terry realized that he had erred in trading Kiddo Davis away and admitted as much. “Trading Davis for Watkins was the worst boner I pulled as manager of the Giants,” he said.3 In late December the club reacquired the outfielder from the Phillies in exchange for Joe Bowman, a second-year pitcher, and cash.

“Of course I am tickled to be back in New York, which is the ballplayers’ paradise,” Dan Daniel quoted Davis as saying. “I’m in good shape right now. I work out nearly every day, never indoors. Right now I do a lot of ice skating. During the fall I played football — not the hard, tackling game but one suited for conditioning rather than injuries.”4

The Giants had supplemented their outfield of Ott and Jo-Jo Moore with a hard-hitting newcomer, Hank Leiber. A rookie of promise, Jimmy Ripple, joined the squad in 1936. So Davis was relegated to backup duty the next two seasons, often as a defensive replacement in the late innings. He batted .264 in 47 games for a third-place Giants team in 1935, and just .239 in a like number of games the following year, when Terry’s club held off charges from the Cardinals and Cubs and won the National League pennant by five games. Davis did, however, thump a pair of home runs as a pinch-hitter in 1935.

In the 1936 World Series, against the Yankees, Kiddo Davis made four appearances, twice as a pinch-hitter and twice as a pinch-runner. In Game Two he singled off Lefty Gomez and scored a run. But the Yanks won in a rout, 18-4. Davis entered the fourth game as a pinch-runner for Sam Leslie in the eighth inning and scored the Giants’ second run in a 5-2 Yankee triumph.

In the Series finale — and what would be his World Series coda — Davis flied out to left against Yankee reliever Johnny Murphy in the eighth inning as the Bronx Bombers wrapped up the fall classic in six games with a 13-5 victory at the Polo Grounds. When the 1937 season opened, he was 35 years old and still the Giants’ principal outfield backup behind Ott, Moore, and Ripple. The club would win yet another pennant, but Davis wasn’t present for the celebration. He refused to accept a demotion to Jersey City (International League) in late July, and the Giants sold him to the Cincinnati Reds, a last-place outfit, on August 4. Combined, he batted .259 in 96 games. Still, there were moments with the Reds when Davis provided a glimpse of past glories. In a 4-1 triumph over the Dodgers at Crosley Field on August 7, he took away a pair of extra-base hits from Heinie Manush, a lifetime .330 hitter later elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“The first time, he went back to the base of the centerfield wall which is far enough from the home plate to be in another county and caught a prodigious poke,” Tommy Holmes wrote in the Brooklyn Eagle. “On the second occasion, he executed a spinning, diving catch of a line drive that Heinie seemed to have safely propelled down the left center alley.”5

Davis began to have mixed feelings about continuing his baseball career; in fact, he announced — and then rescinded — his retirement during the Reds’ 1938 spring training. “A few days ago I thought I had enough of baseball. I thought I could not do justice to myself or my club as a utility player, and I believed the honest thing to do was quit,” he said an Associated Press dispatch. ”It was just one big mistake.”6

Davis eventually joined the Reds in early April, but appeared in just five games and batted .278. He concluded the summer with Jersey City, hitting just .202 against International League pitching before being released by Cincinnati on August 1.

“I was lucky to be allowed the privilege to play a game I loved and receive pay for it,” he later told columnist Edward J. Shugrue of the Bridgeport Sunday Post.7

Unlike so many of his peers, Davis was prepared for post-baseball life. Already a partner in an accounting firm in his native Bridgeport before his playing days ended, he earned a comfortable living as a certified public accountant for many years.

Although out of the limelight, Davis was well-remembered by his home state’s sports community. In 1962 he was presented the coveted Gold Key award at the Connecticut Sports Writers’ Alliance’s annual dinner. Former Yankees pitcher Frank “Spec” Shea (Naugatuck) and Maurice Podoloff (New Haven), the founding president of the National Basketball Association, were the other recipients.

A decade later, Davis was inducted into the New York University Sports Hall of Fame along with basketball All-American Sid Tanenbaum and Emil Von Elling, who coached the Violets track teams for more than 40 years. He later was joined in the NYU Hall of Fame by three other major leaguers of note, Ralph Branca, Eddie Yost, and Sam Mele.

Kiddo Davis died at the age of 81 on March 4, 1983. He was survived by his wife and son; two grandchildren, Ellen and James; and several nieces and nephews.

Sources

The author is indebted to George W. Davis, Jr. and Edna Miller, Kiddo Davis’s niece, for sharing their memories of the late outfielder in interviews during the spring of 2013.

“A Great Player Leaves Our Midst,” Connecticut Elders, April 1983.

Ancestry.com.

Associated Press, “Repairs Among Median Line Helped Giants to Win National Loop Flag,” September 23, 1935.

The Baseball Encyclopedia,10th Edition (New York: Macmillan, Edition, 1996).

Baseball-Reference.com.

Bielawa, Michael J., Bridgeport Baseball (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

Burr, Harold C., “Young George Davis Looks Like Fixture in Phillies’ Garden,” New York Post, undated.

Burr, Harold C., “Davis New King of Giant Corps,” New York Post, April 4, 1936.

Cohen, Leonard, “Davis of N.Y.U. Batting Fame Joins Yankees,” New York Evening World, June 4, 1926.

Daniel, Dan, “Terry Gives Joe Bowman and Cash for Outfielder,” New York World-Telegram, December 13, 1934.

Daniel, Dan, “George Davis, Back with Giants, Hopes He’s Now Off that Baseball Carousel,” New York World-Telegram, January 5, 1935.

“Daniel’s Dope,” New York World-Telegram, April 9, 1932.

Davis, George “Kiddo,” Obituary. Bridgeport Post-Telegram, March 5, 1983.

Davis, George “Kiddo,” Obituary. New York Times, March 8, 1983.

“Davis Will Rejoin Reds; Decision to Quit ‘Mistake,’” New York Times, April 10, 1938.

Drebinger, John, “Davis, Outfield ‘Insurance Man,’ Accepts Contract with Giants,” New York Times, January 13, 1937.

“Frothy Facts,” New York World-Telegram, July 3, 1934.

George “Kiddo” Davis’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Graham, Frank, Lou Gehrig: A Quiet Hero (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1942).

Holmes, Tommy, “Flock Tumbled To 7th Place in 4 to 1 Setback,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 8, 1937.

“Kiddo Davis Honored,” New York Times, March 6, 1971.

“Kiddo Davis Too Tough for Chicago Pitcher in Personal Battle,” New York Sun, September 16, 1933.

Kieran, John, “Sports of the Times: Black Magic,” New York Times, September (date unavailable), 1933.

McConnell, Bob, and David Vincent, eds., The Home Run Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan, 1996).

“N.Y.U. Swatsmith Will Make Tour of West with Yankees,” New York American, June (date unavailable), 1926.

“N.Y.U. to Honor Tanenbaum, Davis and Von Elling,” New York Times, April 23, 1972.

Parker, Charles E., “Davis Defends Bartell,” New York World-Telegram, December 22, 1934.

Retrosheet.com.

Shugrue, Edward J., “Between Ourselves,” Bridgeport Sunday Post (date unavailable), 1946.

Smith, Ken, “Giants Capture Two From Cubs, 5-1, 4-0,” New York Daily Mirror, September 16, 1933.

Notes

1 New York Sun, September 16, 1933.

2 John Kieran, New York Times, September 1933. (Date unavailable)

3 Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram, December 13, 1934.

4 Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram, January 5, 1935.

5 Tommy Holmes, Brooklyn Eagle, August 8, 1937.

6 Associated Press, April 9, 1938.

7 Edward J. Shugrue, Bridgeport Sunday Post, 1946. (Date unavailable)

Full Name

George Willis Davis

Born

February 12, 1902 at Bridgeport, CT (USA)

Died

March 4, 1983 at Bridgeport, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.