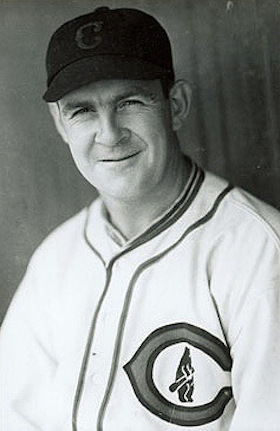

Larry French

One of the most overlooked and underrated pitchers of the 1930s, southpaw Larry French was a “glutton for work,” according to the Pittsburgh Press.1 Over a seven-year stretch (1930-1936), French relied on a devastating screwball and good control to average 16 wins and 268 innings per season; during that time only Carl Hubbell logged more innings, and only Hubbell and Dizzy Dean won more often. Traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1935, French helped lead the North Siders to a pennant that season and again in 1938. Seemingly washed up at the age of 33 in 1941, French developed a knuckleball and posted a stellar 15-4 record and 1.83 ERA for the NL runner-up Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942. He enlisted in the US Navy the following year and wound up making a career of it: He wound up his baseball log with 197 wins and 40 shutouts, tied for 22nd most in baseball history at the time he entered the Navy.

One of the most overlooked and underrated pitchers of the 1930s, southpaw Larry French was a “glutton for work,” according to the Pittsburgh Press.1 Over a seven-year stretch (1930-1936), French relied on a devastating screwball and good control to average 16 wins and 268 innings per season; during that time only Carl Hubbell logged more innings, and only Hubbell and Dizzy Dean won more often. Traded to the Chicago Cubs in 1935, French helped lead the North Siders to a pennant that season and again in 1938. Seemingly washed up at the age of 33 in 1941, French developed a knuckleball and posted a stellar 15-4 record and 1.83 ERA for the NL runner-up Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942. He enlisted in the US Navy the following year and wound up making a career of it: He wound up his baseball log with 197 wins and 40 shutouts, tied for 22nd most in baseball history at the time he entered the Navy.

Lawrence Herbert French was born on November 1, 1907, in Visalia, a small farming town located in the fertile San Joaquin Valley in central California. His parents were George Preston French, a one-time deputy sheriff and carpenter, and Corda May (Davidson) French. By the time Larry was an early teenager, his parents had divorced. He and his younger sister, Gwendolyn, remained with their mother, living at her parents’ house in Visalia, according to the 1920 census. By all accounts, Larry was an athletic youngster and began playing baseball by the age of 10. In addition to suiting up for Visalia High School, he established his reputation as a hard-throwing lefty and pitched four no-hitters while playing for town and semipro teams in Visalia, and in Sutherlin, in west-central Oregon, where his father had relocated.

Tossing two shutouts (including a no-hitter) for a semipro team in Harrisburg, Oregon,2 French caught the attention of Tom Turner, a scout for the Philadelphia Athletics and the co-owner of the Pacific Coast League’s Portland Beavers, as well as Roy Mack, Connie Mack’s son, who had served as Portland’s business manager. In 1926, they signed the 18-year-old, who logged 17 innings for Portland before being optioned to the Ogden Gunners of the Class C Utah-Idaho League, where he went 8-7 and hurled 134 innings.3

The youngest player on the Beavers, French racked up 11 wins in each of the next two seasons, and demonstrated that he could start regularly and occasionally relieve. Described as the “prize lefthander of the circuit,” French attracted big-league scouts, notably from the Athletics and Pittsburgh Pirates.4 Joe Devine, West Coast scout for the Pirates, who had already signed stalwart right-hander Ray Kremer and the hitting sensations Lloyd and Paul Waner from the Coast League, considered French a can’t-miss prospect even though he suffered from a “sore arm” for part of the 1928 season, and compiled a pedestrian 23-29 record and 449 innings in just over two seasons in the PCL.5 On Devine’s recommendation, the Pirates purchased French for an estimated $50,000 and three players in December 1928.6

In 1929 French joined the Pirates, who had finished in the first division every season since 1918. He made his debut on April 18, tossing the final four innings in an 11-1 loss to the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field, yielding four hits and three runs. His first start was more memorable: On May 7 against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, he tossed a 10-inning complete-game victory. “He has plenty of stuff,” wrote Pirates beat reporter Ralph S. Davis, as French hurled complete games to win his next two decisions. “[He] is one of the coolest and collected rookies the ball club has had.”7 Bothered by nagging arm and knee pain most of the season, French missed large chunks in June and July complaining of “weakness and loss of weight.”8 In the last game of the season, he went the distance to subdue the Cubs and conclude his rookie campaign with a 7-5 record and 4.90 ERA in 123 innings.

French had a big, sturdy build, stood about 6-foot-1, and weighed anywhere from 190 to 205 pounds. He was known to take care of his health (and girth) and was among those pitchers who generally arrived in camp in good physical shape. Of Scotch-Irish descent, French had short dark hair and eyes, and was often called good looking in the press. Sportswriters often made reference to his wardrobe; “[French] cops the title as best dressed man,” wrote the Don Roberts of the Newspaper Enterprise Alliance news service.9

French married Thelma Grace Olmstead of Oregon on May 2, 1928. They had one child, Larry French Jr. In the offseason, the Frenches resided in Brentwood, a well-to-do suburb in western Los Angeles. By all accounts, French had good business sense and dabbled in real estate. The Sporting News often reported that he helped his teammates with financial matters. In an era in which players’ salaries were routinely slashed, French was known as a hard negotiator and an annual holdout. His hobbies included hunting and fishing with teammates, and he also regularly participated in barnstorming events and winter-league baseball in the Los Angeles area.10

French had a reputation as a fun-loving teammate. The Pittsburgh Press described him as a “good natured chap, who mixes fun with his baseball labors.”11 His Cubs teammate Phil Cavarretta claimed he was a practical joker and a master at the hotfoot.12 Sportswriter Henry L. Farrell called him the “mouthiest moundsman” for defying custom by jockeying from the mound and bench.13 In his early years French was known for his temper, especially directed at umpires whose calls he didn’t like. Sportswriter Fred Lieb referred to him as a “hothead.”14 He recounted an episode in 1931 when “French almost started the war ten years before Pearl Harbor.” Herb Hunter and Lieb led a group of big-league all-stars, including the likes of Lou Gehrig, Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, and Lefty Grove, to Japan in November and December 1931. To the shock of the Americans, the Japanese All-Stars knocked French out in the seventh inning in one game after which the stout lefty began storming around the field and using racial slurs before Lieb could calm down the irate hurler.15

The mood in Pittsburgh was filled with excitement as the 1930 season opened. Jewel Ens, who had replaced the combative Donie Bush the previous August and had led the Bucs to a second-place finish, piloted the youngest team in the league. In his season debut, French took a no-hitter into the seventh inning against the Cincinnati Reds, finishing with the first of his three career two-hitters and a 2-1 victory.16 After a hot start (8-1), the Pirates’ pennant aspirations were derailed by a porous defense and a surprisingly weak staff. An exception was the 22-year-old French, who proved to be a workhorse and a capable hitter. On May 27 he hurled his third complete game in seven days and knocked in three runs in an 8-5 victory over the St. Louis Cardinals. For the fifth-place Bucs, French laid claim to the title as best southpaw in the NL, leading all lefties in starts (35), complete games (21), and innings (274?), and tying Carl Hubbell with 17 wins. He also led the loop in losses (18), but finished with a sturdy ERA (4.36) in the “Year of the Hitter,” when the NL batted a collective .303 and scored an average of 5.68 runs per game. “I don’t have a lot more stuff than I had in the minors,” said French when asked to explain his success in 1930. “I have learned how to use it better.”17

Considered by Harvey J. Boyle of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as a “thinking pitcher,” French was both reflective and pragmatic.18 “The difference between a great pitcher and a poor pitcher,” he once said, “is just about one line drive a game. If they catch it for you, you’re a great pitcher.”19 French yielded a lot of line drives – a career-high 325 hits on 1930 – and led the league in the dubious category the next three seasons. But unlike many lefties, French had excellent control (ranking among the top 10 six times in fewest walks allowed per nine innings), which helped mitigate the effect of the hits. “I never figure on [hitters’] reputation,” he said. “I just see a ball player up there and pitch to him to the best of my ability.”20

Never a hard thrower, French relied primarily on breaking balls, changeups, and an occasional fastball for his success. His main weapon was the screwball, and he and Carl Hubbell were often described as “the two leading screwball pitchers” in the big leagues.21 “The screw ball is a right hander’s curve ball thrown by a left-hander,” explained French about his pitch, which broke about 8 to 10 inches down and away. “It is thrown with a loose grip with the fingers across the seams, and it revolves rapidly.”22

En route to their first losing season since 1917, the Pirates stumbled to another fifth-place finish in 1931. French, plagued by appendicitis and stomach pain, pitched inconsistently in the first half of the season.23 On July 15 he commenced a “phenomenal” stretch by hurling five consecutive complete-game victories, including a four-hit shutout sandwiched between the two longest outings of his career (14 innings against Brooklyn and 12 innings against St. Louis).24 Finishing the season with a 15-13 record, 20 complete games, and a 3.26 ERA, French ranked second in the NL in innings for the second straight year (275?); and led all southpaws in innings and starts (33).

The death of long time longtime Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss on February 2, 1932, signaled the end of an era in Pirates history as the club would not win a pennant until 1960. Pittsburgh started the 1932 season slowly (in last place with a 9-17 record) before unexpectedly winning 50 of 71 games and surging to a six-game lead in the pennant race on July 9. The unequivocal ace of the club, French seemed to fulfill Lefty Grove’s prediction that he’s “destined to become one of the greatest hurlers in the National League.”25 Often the victim of bad luck and poor run support, French recorded one of his six victories against the reigning champion Cardinals when he blanked them on two hits on May 20. In the first game of a doubleheader on July 26, his shutout against Cincinnati pushed the Pirates into an unlikely tie with Chicago for first place in a heated pennant race. Described by Pirates beat writer Ralph S. Davis as a “veritable workhorse,” French regularly pitched on two and three days’ rest over the last seven weeks of the season (registering nine wins and completing 10 of 12 starts) as first-year manager George Gibson’s only consistent hurler while the team took a nose dive. The husky Californian went 18-16, completed 20 of 33 starts, led the NL with 47 appearances, and carved out a 3.02 ERA in 274? innings.

A hallmark of consistency, French was annually touted as a 20-game winner, yet never had that career season when everything seemed to fall in place and resulted in 20-25 wins. Ralph S. Davis suggested that “luck” and “fate” were against French, who would someday shake the “jinx” that followed him.26 His best season may have been for the runner-up Bucs in 1933 when he tied his career high with 18 wins, 21 complete games, 35 starts (which also led the league); his 2.72 ERA was the best in his career.

In light of reports that French was an outspoken critic of Gibson’s managerial style, rumors about the lefty’s trade circulated in the offseason and continued through the 1934 campaign as the underachieving Pirates floundered.27 Pie Traynor was named player-manager in June, but could do little to stave off a losing season and a fifth-place finish. French led the staff in practically every category, but fell to 12-18. On November 22 the Pirates shipped French and future Hall of Famer Freddie Lindstrom to the Chicago Cubs for pitchers Guy Bush and Jim Weaver, and outfielder Babe Herman.

Since winning the pennant in 1932, the Cubs had two disappointing third-place finishes, and retooled with pitching in ’35. Beat reporter Edward Burns was not impressed with the acquisition of French and brooding right-hander Tex Carlton from St. Louis, and considered the staff “short of pennant class.”28 Burns’s prediction initially seemed correct, as French got off to a slow start, losing five of his first seven decisions. But in June he showed the Cubs that he was the best lefty in the NL not named Hubbell by winning five straight decisions, including two shutouts, the latter of which was an impressive 12-inning 1-0 victory over the Pirates on June 29. On July 4 the Cubs were firmly ensconced in fourth place, 10½ games off the lead, before going on a 24-3 romp to climb back into contention. On September 4 French tossed a complete game to defeat Philadelphia and commence one of the most spectacular streaks in baseball history as the Cubs won 21 straight games. French won five of them, all complete games, and yielded just six earned runs as the Cubs captured the pennant. French (17-10, 2.96), Bill Lee (20-6, 2.96), and Lon Warneke (20-13, 3.06) anchored a staff that led the league in ERA. For the first of two straight seasons, French tied for the league lead with four shutouts.

Skipper Charlie Grimm’s North Siders faced the Detroit Tigers in the World Series, which is best remembered for the verbal (anti-Semitic) abuse the Cubs heaped on slugger Hank Greenberg. Befitting his “jinxed” reputation, French lost two games in heartbreaking fashion. He hurled the final two innings of relief in Game Three, and was collared with the loss when third baseman Lindstrom (with whom French had supposedly feuded since their days in Pittsburgh), committed an error on a possible inning-ending double play in the 11th inning leading to a run two batters later.29 French started Game Six and yielded a dramatic two-out, Series-clinching, walk-off single to Goose Goslin in a 4-3 loss.

In 1936 and 1937 French tied for the Cubs’ lead with 18 and 16 wins respectively as the club finished in second place each season. In the latter year, he suffered his first major injury when three fingers on his hand were broken by a line drive from Cincinnati’s Ernie Lombardi, and missed approximately five weeks. “Larry didn’t get the credit he deserved,” said teammate Phil Cavarretta. “[He was] a better pitcher than a lot of people thought he was, because he didn’t throw hard. He had a real good screwball, had a pretty good curve. He would never beat himself. You had to beat him. So many hitters went up and faced him and would say, ‘Jesus, with that garbage you’re throwing, how the hell can you get anybody out.’ ”30

Despite complaints of “arm soreness” as training camp ended in 1938, French tossed a four-hit shutout in his season debut.31 He then lost 15 of his next 21 decisions, prompting Cubs beat writer Irving Vaughan to quip, “[French’s] recent misfortunes exceed in number the rabbit hooves, voodoo chasers, and other charms he is carrying around.”32 After catcher Gabby Hartnett replaced Grimm as player-manager on July 21, French moved into the role of swingman for the first time in his career, and made only seven more starts. The Cubs went on a tear, winning 28 of their last 38 games, highlighted by Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’” on September 28, to capture the pennant; however, French struggled, yielding 49 hits and 20 earned runs in 24 innings from August 16 to the end of the season. He finished with a disappointing 10-19 record, but logged 200 or more innings for the ninth consecutive season. In Chicago’s four-game sweep at the hands of the New York Yankees, French made three relief appearances, surrendering one hit (a homer to Bill Dickey) and a run in 3? innings.

French rebounded with a 15-8 record and 3.29 ERA in 1939. The summer months were consumed by reports in the Chicago press that French was in Hartnett’s “doghouse” or that the players were feuding, given that the 31-year-old hurler made only one start between June 15 and August 8.33The following season, French tossed three shutouts his first five starts, and earned his only berth on an All-Star team. He hurled two scoreless innings in the NL’s 4-0 victory. A modest player who never sought the spotlight, French was quick to give his future Hall of Fame catcher credit. “Hartnett taught me more about pitching in two weeks than I had learned in Pittsburgh for six years. He got me to do two things. … One was to throw my curve ball to right-handed hitters, and the other was to throw my screw ball to left-handed hitters.”34 French also took advice from former Cleveland workhorse George Uhle, who served on the Cubs’ coaching staff in 1940. “[H]e showed me how, by taking a little longer stride, I could break my curve ball high and inside on a right-handed hitter.”35 French split his 28 decisions, completed 18 of 33 starts (the highest marks since 1934), and posted a sturdy 3.29 ERA in 246 innings.

The 33-year-old French appeared to be washed up in 1941, losing 14 of 19 decisions, and was placed on waivers in August. French later revealed the reason for his struggles: He had broken his left thumb while pitching in a softball game in the offseason and later dislocated it while hunting. He kept the injury a secret from the Cubs, and pitched with an unnatural motion.36 The Brooklyn Dodgers, in a heated pennant race with St. Louis, took a chance on the southpaw. Though he pitched sparingly (15? innings) for skipper Leo Durocher, French was a valued member of the relief corps. In Brooklyn’s five-game loss to the Yankees in the World Series, French made two relief appearances, retiring all three batters he faced.

French rejuvenated his career at the Dodgers’ spring training in Havana by mastering a knuckleball taught to him by teammate Freddie Fitzsimmons. “Fred throws it with a stiff wrist,” said French. “I flip it loose, and when you have a butterfly to chuck in with your high hard one and a change of pace – well, it’s convenient.”37 Called a “gift from heaven” by GM Larry MacPhail and an early season “hero” by beat reporter Tommy Holmes, French was one of the feel-good stories of the season.38 As Durocher’s trusted swingman, French’s season was like a highlight reel: he won his first 10 decisions, tossed an 11-inning complete game to beat the archenemy Cardinals (the 20th and final time he hurled 10 or more innings), fired four shutouts, the last of which was the only one-hitter in his career, and finished with a 15-4 record and 1.83 ERA in 147? innings. “This fellow is truly a great pitcher,” said “Leo the Lip.” “The knuckle ball he developed this season has increased his effectiveness tremendously. He goes fine in relief roles because he’s smart and can throw the ball where he wants.”39 Brooklyn won 104 games, but finished second to the Cardinals in another classic pennant race.

In January 1943 French enlisted in the Navy and was stationed in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Just three wins shy of 200 victories, French, then 35 years old, feared that he might not get a shot at the milestone. He stayed in shape by pitching for the semipro Bushwicks in Brooklyn on weekends and also worked out with the Dodgers. He petitioned the Navy to play part-time for the Dodgers but was denied by Rear Admiral W.B. Young, who was reluctant to set a precedent.40

Young’s decision effectively ended French’s career. In 14 big-league seasons, he posted a 197-171 record and a 3.44 ERA in 3,152 innings. He appeared in 570 games and completed 199 of 383 starts. He batted .188 (199-for-1,057) and knocked in 84 runs.

As stellar as French’s baseball accomplishments were, his 27-year career in the Navy, retiring as a captain in 1969, may have been even more impressive. As a member of Bombardment Group 1 on the battleship New York, French participated in the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, and served for 17 months in the European and Pacific Theaters. There was brief speculation that he would return to baseball in 1946 and 1947, but he scuttled those rumors, returning to Los Angeles, where he owned a new-car dealership and had been involved in car financing since at least the mid-1930s. A member of the Navy Reserve since the conclusion of World War II, French was recalled to active duty in January 1951 as the hostilities on the Korean peninsula intensified. In 1965 he was named commander of the Navy Regional Finance Center in San Diego. Upon retiring in 1969, French received the Legion of Merit award for exceptional service.41

French resided in Point Loma, a coastal community in San Diego, upon his discharge. After his wife, Thelma, died in 1981, he married Barbara Rollins a year later. On February 9, 1987, French died from kidney and heart disease at the age of 79.42 He was buried in his hometown of Visalia.

Syndicated sportswriter Jim Hamilton suggested in 1993 that French was deserving of the Hall of Fame. He argued that a “veteran of three wars,” who sacrificed his last three or four years for the country, should not be not be judged by statistics alone.43 Though some may disagree with Hamilton’s contention, few baseball players, if any, enjoyed two stellar careers as French did.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

SABR.org.

Larry French player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 “Steve Swetonic, Larry French, Just a Couple of Pals,” Pittsburgh Press, July 7, 1932, 23.

2 ”Sutterlin Boy Pitches Winning Game for Beavers,” News-Review (Roseburg, Oregon), June 14, 1927, 5. Edward F. Ballinger, “Pirates of 1932,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 24, 1932, 14. The circumstances of how Tom Turner purchased the Portland Beavers are murky. He was supposedly financed by the Shibe family in Philadelphia. For more on Turner’s and Roy Mack’s involvement, see Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915-1931 (Omaha, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 346-349.

3 “Beavers Send Twirler Here,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, June 20, 1926, 13.

4 The Sporting News, September 22, 1927, 2.

5 “Portland Club Sells French To Pirates,” Oakland (California) Tribune, December 13, 1928, 36.

6 Ibid.

7 The Sporting News, May 16, 1929, 3.

8 The Sporting News, August 1, 1929, 3.

9 Don Roberts, Newspaper Enterprise Association, “Pirates of 1930 Are Real Swanky Outfit,” Klamath (Oregon) News, April 16, 1930, 6.

10 James Newton of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s most important black newspapers, reported about a pitching duel between Satchel Paige and French in LA when the latter played for the Joe Pirrone All Stars. Paige whiffed 14 and his squad defeated French, 5-0. “ ‘Satchell’ (sic) Has ‘His Day’ Oncoast (sic), Larry French Pirates Ace, Beaten, 5-0,” November 25, 1933, 14.

11 “Larry French, “Pirate Southpaw, May Sing Rival Batsmen to Sweet Sleep,” Pittsburgh Press, March 15, 1930, 15.

12 Golenbock, Wrigleyville. A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 257.

13 Henry L. Farrell, “Baseball’s New Crop of Jockeys,” Santa Ana (California) Reporter, July 21,, 1929, 22.

14 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1948) 242.

15 Frederick G. Lieb, Baseball As I Have Known It (New York: Putnam and Sons, 1977), 203.

16 Associated Press, “Larry French Almost Enters Hall of Fame,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republic, April 18, 1930, 18.

17 Harvey J. Boyle, “Mirrors of Sport,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 7, 1930, 17.

18 Boyle.

19 “What Makes a Hero,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, October 31, 1933, 6.

20 The Sporting News, May 16, 1929, 3.

21 Jack Cuddy, United Press, “Pittsburgh Wants Revenge For That 1921 Catastrophe,” Hammond (Indiana) Times, September 6, 1933, 10.

22 “Cubs Seeking to Bolster Weak Outfit; May Not Have to Travel Far,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 3, 1933, 23.

23 “Doctors Fear Larry French Is Suffering From Appendicitis,” Franklin (Pennsylvania) News-Herald, July 9, 1931, 1.

24 Gayle Talbot Jr., Associated Press, “Larry French Looks Like Leading Southpaw in 1931,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, August 6, 1931, 8.

25 Harold C. Burr, “ ‘Ruth Is Good For Five Years More,’ Says Gehrig,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 18, 1932, 20.

26 The Sporting News, August 31, 1933, 3.

27 Harold Parrott, “Bucs To Trade Larry French, Gibson Critic,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 24, 1933, 20.

28 Edward Burns, “Cubs Pitching Staff Short of Pennant Class,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 13, 1935, A3.

29 The Sporting News, October 17, 1935, 3.

30 Golenbock, 254.

31 Irving Vaughan, “French Faces Lyon In Series Final,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 17, 1938, B2.

32 Irving Vaughan, “White Sox Win, 11-3; Cubs Beat Phils, 4-1,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 16, 1938, 13.

33 The Sporting News, August 10, 1939, 5.

34 Frank Graham, dated June 26, 1940. [Unattributed article in player’s Hall of Fame file].

35 Ibid.

36 Arthur E. Patterson [Unattributed article in player’s Hall of Fame file], and The Sporting News, June 30, 1942, 1.

37 Dan Daniel, “Sensational Comeback of Larry French A Dramatic Story,” New York World-Telegram, July 23, 1942.

38 The Sporting News, April 16, 1942, 1, and May 14, 1942, 5.

39 Tommy Devine, “Revenge, Bonus Drive Larry French to Role of Top Major League Pitcher,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 18, 1942, 7.

40 United Press, “Larry French Out As Dodgers Pitcher,” Eugene (Oregon) Register Guard, April 18, 1943, 17.

41 The Sporting News, December 20, 1969, 47.

42 Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 137.

43 Jim Hamilton, “French Earned Fame,” Oneonta (New York) Star, May 24, 1993.

Full Name

Lawrence Herbert French

Born

November 1, 1907 at Visalia, CA (USA)

Died

February 9, 1987 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.