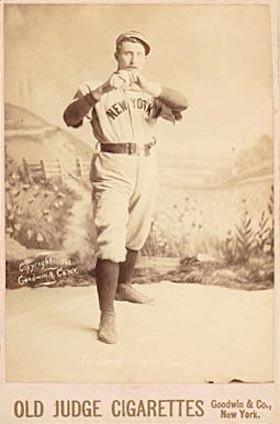

Ledell Titcomb

While he was hardly a late-nineteenth-century pitching standout, left-hander Ledell Titcomb’s six-season major-league career was not without accomplishments. As a spot starter, he contributed 14 victories to the National League pennant-winning effort of the New York Giants in 1888. Two seasons later, Titcomb authored a no-hitter for Rochester in its only campaign as a big-league club. But soon thereafter, arm miseries brought his hurling days to a premature end. Titcomb spent the remainder of his long life in quiet obscurity, mostly working as a shoemaker.

While he was hardly a late-nineteenth-century pitching standout, left-hander Ledell Titcomb’s six-season major-league career was not without accomplishments. As a spot starter, he contributed 14 victories to the National League pennant-winning effort of the New York Giants in 1888. Two seasons later, Titcomb authored a no-hitter for Rochester in its only campaign as a big-league club. But soon thereafter, arm miseries brought his hurling days to a premature end. Titcomb spent the remainder of his long life in quiet obscurity, mostly working as a shoemaker.

Shortly before Titcomb’s death at age 83, a curious phenomenon occurred. He was given a nickname that had never appeared in newsprint during his actual playing days: Cannonball. The moniker was premised on a likely apocryphal tale about Titcomb in his youth published in his former hometown newspaper. In June 1950, this newly coined nickname was embraced by the Associated Press in circulating an obituary for Titcomb. And Cannonball Titcomb is how our subject is listed in Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and other baseball reference works today. A forensic examination of the events that spawned this historically dubious appellation appeared in an issue of Nineteenth Century Notes, the quarterly newsletter of SABR’s 19th Century Committee.1 For present purposes, suffice it to say that the Cannonball nickname is highly suspect, and in need of serious reassessment by baseball historians. In the meantime, the instant piece is devoted to telling the life story of the player known to family, friends, and the baseball world of his time as Ledell Titcomb.2

Titcomb3 was born on August 21, 1866, in West Baldwin, Maine, an apple-growing village not far from the border with New Hampshire. He was the second of four children born to carpenter Joseph J. Titcomb (1834-1908) and his wife, Fannie (the former Mary Frances Burnell, 1838-1893).4 By the time Dell (as teammates sometimes called him)5 was a teenager, the family had relocated to Wakefield, Massachusetts. A smallish (5-feet-6, 157 pounds) lefty batter and thrower, Titcomb began playing ball on local sandlots before graduating to faster competition. In April 1884 he became a charter member of an amateur club formed in nearby Haverhill.6 Originally a first baseman but near-helpless with the bat, Titcomb was converted into a pitcher later that season.

When Haverhill entered the professional Eastern New England League in 1885, Titcomb remained with the nine and pitched effectively during the early going. But in August, a lackadaisical performance against Lawrence – perhaps the first manifestation of the attitude and maturity problems that would surface periodically during Titcomb’s pro career – led to his indefinite suspension. Titcomb responded by demanding his release by the Haverhill club.7 In time, club management capitulated, leaving Titcomb free to offer his services elsewhere. Taking note of these developments was renowned manager Harry Wright, then in charge of the National League Philadelphia Quakers. Previously in June, Titcomb had impressed Wright by pitching Haverhill to a 2-1 exhibition-game victory over the Quakers. Once Titcomb became available, Wright signed him for the 1886 season.8

Despite his unimposing stature, the 19-year-old Titcomb threw hard. But he also got outs with a puzzling assortment of breaking pitches. As spring camp approached, Sporting Life’s Haverhill correspondent predicted success, for “under the handling of an expert manager like Harry Wright, [Titcomb] should make a good record as he has great speed and all the curves. All he needs is a good coach.”9 Dell got off well, dominating the Brown University varsity in a spring exhibition contest. But against National League competition, his fortunes changed. On May 5, 1886, Titcomb made a creditable major-league debut, holding the New York Giants to three hits while striking out eight, but dropped a 4-2 decision. He was hit hard, however, in two of three subsequent starts, all losses. Then, off-field horseplay with fellow Quakers pitcher Ed Daily left Titcomb sidelined with a broken right arm.10 He returned to action in time to take a late-season 11-0 clobbering from Detroit. Dell finished the 1886 campaign at 0-5 in five complete games pitched for a first-division (71-43) Philadelphia club. Notwithstanding his winless log, manager Wright retained high hopes for Titcomb and re-signed him for next year.11

Titcomb reported for Quakers spring camp “in much better shape than ever before, and display[ed] much better judgment in handling the ball,” reported Sporting Life.12 But plagued by control problems and a lack of pitching savvy, he did not make the club’s roster. Instead, Titcomb began the 1887 season with a local rival, the Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association. Reunited with former Haverhill batterymate (and future Hall of Famer) Wilbert Robinson, Titcomb was expected to excel. But he proved a bust. He eked out a 10-9 victory over Brooklyn on April 30 to record his first major-league win, but was ineffective the next two times out, dropping both decisions. Widely deemed “a failure for the Athletics,”13 Titcomb was unconditionally released in early May. Several days thereafter, he signed with the Jersey City Skeeters of the minor International League.14

Paired with catcher Pat Murphy, Titcomb finally began to fulfill expectations. He got off well with Jersey City, winning his first three starts. He then attained the dubious distinction of losing a game in two separate cities on the same date. On the morning of May 17, Titcomb dropped a 3-2 decision to Newark in a game played in Jersey City. That afternoon, the clubs reconvened in the nearby Newark ballpark where Titcomb was an 11-1 loser. That unhappy couplet, however, proved anomalous. Titcomb pitched consistently excellent ball for Jersey City, and by late August, Sporting Life’s local correspondent was calling him “the best hurler in the International League.”15 The little lefty’s good work did not go unnoticed, and several major-league clubs expressed interest in him, and in catcher Murphy as well. In late August, the battery was sold to the New York Giants for a reported $3,000.16

On September 2 the duo made an impressive debut in a 2-1 victory over Detroit, with the New York Herald rhapsodizing, “Titcomb … scored an emphatic success, his left-handed delivery being an enigma to the Titans from Detroit. He was splendidly supported by Murphy whose back up work and throwing were as fine as any seen in the Polo Grounds this season.”17 The New York Tribune was equally enthusiastic about the newcomers: “Titcomb has plenty of speed, marvelous curves and reasonably good control of the ball, and ought to be of good service to the nine. Murphy caught nicely and his throwing to the bases was exceptionally rapid and accurate.”18 But after that, their work was sketchy. Titcomb finished his brief tour with the Giants at 4-3, with a 3.88 ERA in 72 innings pitched, while Murphy batted .241 in 17 games for the fourth-place (68-55) club. Still, their showing was sufficient for New York to retain the pair for the following season.19

Over the winter, Titcomb purchased property in Haverhill and apprenticed in a local shoemaking shop, learning the trade that he would pursue for most of his post-baseball life.20 On 1888 Opening Day in Washington, he was the unlikely starter for the Giants and turned in a three-hit, 6-0 victory over the Senators. With Pat Murphy serving as his personal backstop,21Titcomb won his next four starts as well before dropping a 9-3 decision to Chicago in mid-May. Thereafter, he settled into a spot starter role, reliably spelling staff aces (and future Hall of Famers) Tim Keefe (35-12) and Mickey Welch (26-19), each of whom hurled over 400 innings. On October 10 Titcomb recorded a one-hit, 1-0 victory over Pittsburgh to bring an excellent season to a close. For a NL pennant-winning (84-47) Giants club, he went 14-8, with a 2.24 ERA in 197 innings pitched, and ranked second among league hurlers in strikeouts per nine innings pitched. But Titcomb saw no action in the postseason championship match against the American Association title-holding St. Louis Browns until after the Giants had already clinched the best-of-10-games-played series. Dell was charged with the loss in the meaningless final contest, but most of St. Louis runs scored in that 18-7 farce came off the pitching of Giants infielder Gil Hatfield while Titcomb was stationed in center field.

Although he was only 22 years old, Titcomb’s pitching prime was now behind him. He began the 1889 season shakily, staggering to an 11-10 win over Boston on April 25. Then he was shelled in an 11-2 loss to Philadelphia on May 4. Thereafter, Titcomb and Billy George, another young left-hander equal parts promise and immaturity, got themselves into Giants owner John B. Day’s doghouse. With Mickey Welch taken ill and second-line pitcher Cannonball Ed Crane injured, the club was in dire need of a starter for a May 11 game against Boston. But Titcomb and George were “out of condition” and unavailable,22 necessitating the use of infielder Hatfield in the box. New York lost, 4-3. Amid rumors that his release was imminent, Titcomb received the ball on May 14 and threw six scoreless innings at Cleveland, only to collapse in a five-run seventh that spelled a 5-0 defeat. Shortly thereafter, the Giants released him.23

Despite his youth and recent success, there were no major-league bidders for Titcomb’s services. But he received an outpouring of offers from minor-league clubs. From these, Titcomb signed the contact proffered by the Toronto Canucks of the International League,24 touching off a fleeting circuit controversy. The widely reported $500-per-month salary tendered Titcomb surpassed the $400 IL limit.25 Toronto management promptly denied the salary report, only to have Titcomb himself confirm it.26 In fact, Titcomb and Detroit Wolverines right-hander Lev Shreve were believed the highest-paid pitchers in the International League.27 Whatever his wage, Titcomb amply repaid Toronto. Pitching for the middling (56-55) Canucks, he posted only a 15-13 mark, but led IL hurlers with a sparkling 1.27 ERA in 245⅔ innings pitched.28

Although a strong and vocal union man,29 Titcomb was not sought by any of the teams in the newly formed Players League. Thus, he began the 1890 season where he had left off the previous year, pitching in the minors for Toronto. He went 10-11 in 22 games for the Canucks. But indirectly, the expansion of major-league ranks precipitated by the Players League accrued to Titcomb’s benefit. When the International League disbanded in mid-July, the first-year Rochester Hop Bitters of the struggling-to-survive American Association grabbed Titcomb. He quickly solidified his status with his new club by winning his first three decisions. Thereafter, Titcomb struggled amid reports that his shoulder had gone lame.30

Given such reports, the game-of-a-career performance turned in by Titcomb on September 15 was wholly unexpected. Taking the box against the Syracuse Stars before a sparse home crowd of 543,31 Titcomb was “phenomenal and the Stars did not make anything that had a semblance of a hit.”32 He struck out seven, walked two, and was aided by several brilliant defensive plays behind him in completing the 7-0 masterpiece, one of only two no-hitters thrown in the majors during the 1890 season.33 On October 11 Titcomb near-repeated the feat, throwing a six-inning one-hitter in a 4-3 win over Baltimore. Sadly, he ended the season and, as it turned out, his major-league career on a sour note, giving up 19 hits in a 16-11 loss to that same Baltimore club.

Titcomb, 10-9 in 20 games pitched for the Hop Bitters, was reserved by Rochester for the 1891 season,34 but the Flour City’s tenure as a major-league venue expired over the winter. So did Ledell Titcomb’s pitching arm. He re-signed with the Hop Bitters, now demoted to the minor Eastern Association, for the 1891 season but was shellacked in an early-season outing against Buffalo, losing 18-1. He was released shortly thereafter.35 A one-game audition for a league rival, the Providence Clamdiggers, yielded similar results. On May 27 Titcomb was knocked out of the box in the first inning of a 14-7 drubbing by Albany. Although he was still only 24 years old, the professional pitching career of Ledell Titcomb was over.

In parts of six major-league seasons, Titcomb had gone 30-29 (.508), posting a 3.47 ERA in 528⅔ innings pitched and completing all but one of 62 career starts. Control had often been a problem, as Titcomb’s walks/HBP/wild pitches total (298) exceeded his strikeouts (283). But before his arm went bad, the little southpaw had formidable stuff. His attitude and maturity were another matter. Looking back a near-quarter century later, a non-bylined New York Times sportswriter observed, “Ledell Titcomb … did remarkable pitching during the season of 1888. In fact, he was sensational. [But] Titcomb was too much a comedian to take baseball seriously. [Still], the fellow had rare skill and was a puzzle to all big league batsmen when he felt inclined to do his best.”36 In addition to accumulating deportment demerits, Titcomb had also been a poor baserunner, a worse fielder (.833 FA), and among the most pitiful hitters of the nineteenth century, the possessor of a microscopic .098 career batting average.

Although his baseball days were done early, Titcomb still had near 60 years yet to live. He returned to Haverhill where his father, by now a builder, put Dell to work as a carpenter. In January 1896, Titcomb put bachelorhood behind him, marrying 21-year-old Margaret O’Herne.37 Their union would endure for 54 years but produce no children. From 1900 on, Haverhill directories list Titcomb’s occupation as shoemaker, although from 1914 to about 1920 he served his employer, the United Shoe Machinery Company, as a sales representative. Around 1920, the Titcombs relocated to rural Kingston, New Hampshire, although wife Margaret continued working in nearby Haverhill as a domestic for city gentry, while Dell returned to shoemaking.

For the most part, Titcomb spent these years in obscurity. On occasion, however, the exploits of his baseball playing days were recounted in the local press.38 Conspicuous by its absence from these Titcomb retrospectives was any reference to his having been nicknamed Cannonball. This, however, was hardly noteworthy as contemporary reportage of Titcomb’s playing days was equally bereft of this putative moniker.39 As best as can be determined, the nickname debuted when Titcomb was 82. According to a late 1948 profile published by the Haverhill Gazette, “Those who remember Titcomb will recall that his pitches were so fast that the only fellow who could catch them was Bill [sic] Robinson, who later became manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. His mates at Haverhill nicknamed him ‘Cannonball’ after he split a plank with a pitched ball.”40

As he grew into old age, Titcomb developed heart disease. In early June of 1950 he was admitted to a hospital in adjoining Exeter, New Hampshire, and died there several days later from heart failure.41 He was 83. Titcomb’s death, in turn, triggered propagation of the Cannonball nickname. Although the recently coined moniker found no mention in the obituary published locally,42 the Associated Press began its brief, but error-filled, wire-service story: “Ledell (Cannon Ball) Titcomb … died today,” and expanded the plank-splitting yarn into a feat observed by “old-timers … any number of times.”43 Thereafter, the uncritical acceptance of the Cannon Ball nickname and its underlying story by The Sporting News cemented the AP misinformation in baseball stone.44 To this day, the player known to his contemporaries as Ledell Titcomb is identified as Cannonball Titcomb in Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and other current reference works.45

Back in Kingston, meanwhile, a funeral service for Titcomb was conducted at the First Congregational Church, followed by interment at nearby Greenwood Cemetery. Immediate survivors were confined to the deceased’s wife, Margaret, and his sister, Flora Titcomb Hoague.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info provide herein include the Ledell Titcomb file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Titcomb family tree and US Census data accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 See Bill Lamb, “Ledell (Not Cannonball) Titcomb: Tracing the Origins of a Dubious Nickname,” Nineteenth Century Notes, Fall 2016.

2 As was customary during the late nineteenth century, Titcomb was usually referred to only by his surname. When his first name did appear in newsprint, it was invariably given as Ledell. At no time was the nickname Cannonball employed in contemporary reportage. As best the writer can determine, the Cannonball nickname debuted in a late-1948 article in the Haverhill (Massachusetts) Gazette. Titcomb was then 82 years old, with his playing career almost 60 years behind him.

3 On the death certificate informed by his wife of 54 years, Titcomb’s name is given as Ledell N. Titcomb. No other citation of this middle initial was encountered by the writer, and what the N. stood for is unknown.

4 The other Titcomb children were Edgar (born 1858), Florence (Flora, 1864), and Corabell (1869).

5 According to the Ledell Titcomb player questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame library by niece Virginia Bergeron in the early 1970s.

6 As reported in the Boston Herald, April 24, 1884.

7 As per the Boston Journal, August 7, 1885, and Sporting Life, November 18, 1885.

8 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 14, 1885, Sporting Life, November 18, 1885, and Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, November 22, 1885.

9 Sporting Life, February 17, 1886.

10 As reported in the Boston Herald, August 11, 1886, New York Herald, August 16, 1886, and Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 22, 1886.

11 As reported in Sporting Life, March 9, 1887.

12 Sporting Life, March 30, 1887.

13 So branded by the Philadelphia Inquirer, May 7, 1887, Boston Herald, May 8, 1887, and (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, May 23, 1887.

14 As reported in the New York Herald, May 13, 1887, and Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 14, 1887.

15 Sporting Life, August 24, 1887.

16 According to the New York Times, August 27, 1887, Philadelphia Inquirer, August 29, 1887, and Sporting Life, August 31, 1887.

17 New York Herald, September 3, 1887.

18 New York Tribune, September 3, 1887.

19 As reported in the Chicago Inter-Ocean, Cleveland Plain Dealer, and New York Herald, October 19, 1887.

20 As reported in Sporting Life, January 9, 1888.

21 To many observers, Titcomb had “no head at all [and] without Murphy to catch him is utterly powerless to pitch.” See the Aberdeen (North Dakota) News, May 31, 1888, and Sporting Life, June 6, 1888. But with a .170 batting average, Murphy, in turn, owed his Giants roster spot largely to his ability to handle Titcomb.

22 As reported in the New York Times, May 10, 1889, and New York Herald, May 11, 1889.

23 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Wheeling Register, May 19, 1889. The Giants released fellow miscreant Billy George the following month.

24 As reported in the Saginaw (Michigan) News, May 22, 1889, Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 23, 1889, and Sporting Life, May 29, 1889.

25 As per the Watertown (New York) News, May 29, 1889, and Rocky Mountain News, May 30, 1889.

26 See the Watertown (New York) Times, May 30, 1889: Toronto denial; Sporting Life, July 3, 1889: Titcomb confirmation.

27 According to Sporting Life, July 17, 1889.

28 As per The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed. 1997), 114. Baseball-Reference has the Titcomb ERA a tick higher at 1.28.

29 See, e.g., the Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 16, 1890, for a Titcomb prediction of player cohesion and the success of the Brotherhood’s new league.

30 See Sporting Life, August 16, 1890.

31 According to the wire-service box score published nationally. Local newspapers estimated that attendance totaled about 700. See the Rochester Times-Union and Syracuse Journal, September 16, 1890.

32 Cleveland Plain Dealer and Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1890.

33 The other, pitched by the PL Chicago Pirates’ Silver King on June 21 in a losing, eight-inning effort, is no longer recognized as a no-hitter by official record-keepers.

34 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Sporting Life, October 18, 1890.

35 As reported in Sporting Life, May 16, 1891.

36 New York Times, May 9, 1915.

37 Massachusetts marriage records give the bride’s maiden name as Hearn, while US Census and other government records use Herne or O’Herne, the latter being the maiden name specified by niece Virginia Bergeron in the Ledell Titcomb questionnaire that she completed for the Hall of Fame library.

38 See, e.g., “Del Titcomb, Vet of Major and Minor Leagues,” Haverhill (Massachusetts) Gazette, July 11, 1940, and “Kingston Man Was with Giants: Ledell Titcomb Pitched When Wilbert Robinson Was Catcher,” Portsmouth (New Hampshire) Herald, May 3, 1935.

39 The writer’s review of more than 700 news articles printed during Titcomb’s playing days failed to uncover a single instance wherein he was called Cannonball.

40 A copy of this article, captioned “Baseball Recommended as Career by Kingston Oldster,” is contained in the Ledell Titcomb file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center. The clip in the file is unidentified but passages in the text and other circumstances support its attribution to a late-1948 issue of the Haverhill Gazette.

41 As per the Titcomb death certificate, filed June 16, 1950.

42 See “Ledell Titcomb,” Kingston (New Hampshire) News, June 15, 1950.

43 In its six sentences, the AP obit got the date of death wrong; assigned the slightly-built deceased the 200-pound weight of Giants pitching mate Cannonball Crane; and identified Titcomb’s most effective receiver as Wilbert Robinson, rather than Pat Murphy. See, e.g., the [Little Rock] Arkansas Gazette, Canton (Ohio) Repository, and Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, June 10, 1950.

44 The Sporting News, July 7, 1950: “A southpaw, weighing 200 pounds, Titcomb had a fast ball that was said to split planks, resulting in his nickname of ‘Cannon Ball.’”

45 In the original 1951 edition of The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball, by Turkin & Thompson, our subject was listed as “Ledell (Cannon Ball) Titcomb.” By 1979 this had morphed into a “Cannonball Titcomb” listing in the Macmillan baseball encyclopedia. The basis for the name modification is unknown to the writer.

Full Name

Ledell Titcomb

Born

August 21, 1866 at West Baldwin, ME (USA)

Died

June 8, 1950 at Exeter, NH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.