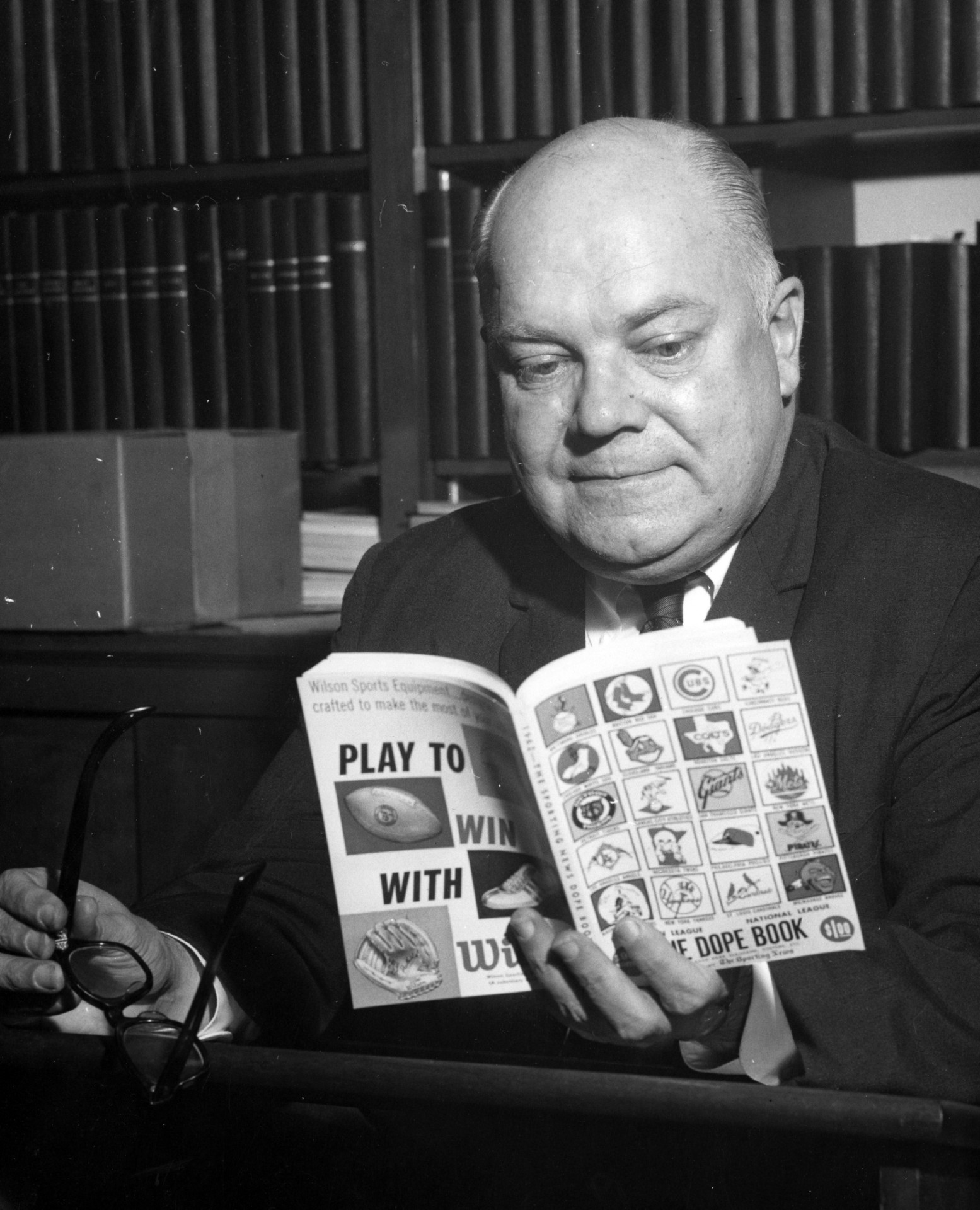

Lee Allen

At the time of his death in 1969, Lee Allen had been the historian at the Hall of Fame’s National Baseball Library for ten years. He was widely celebrated for his encyclopedic recall of persons famous and obscure, events large and small. “I care very little for statistics as such,” he always said. “My concern is the players. Who are these men? What are they? What problems have they faced? Where are they now?” Allen dedicated his life to asking these questions and then to answering them. He demonstrated his knowledge on radio programs and television shows and was a prolific writer whose books and articles marked him as the foremost baseball historian of his time.

At the time of his death in 1969, Lee Allen had been the historian at the Hall of Fame’s National Baseball Library for ten years. He was widely celebrated for his encyclopedic recall of persons famous and obscure, events large and small. “I care very little for statistics as such,” he always said. “My concern is the players. Who are these men? What are they? What problems have they faced? Where are they now?” Allen dedicated his life to asking these questions and then to answering them. He demonstrated his knowledge on radio programs and television shows and was a prolific writer whose books and articles marked him as the foremost baseball historian of his time.

Some boys dream of a life in the circus; others, like Lee Allen, dream of a life in baseball. Born in 1915, he was the son of a Cincinnati attorney who served three terms in Congress. Having seen his first Reds game while still in knee pants, Allen was a regular at Redland Field (later Crosley Field) by the time he entered Hughes High School. Whether he cajoled the principal into letting him escape from class early, as some romantic accounts have it, or whether the school day ended before the late afternoon games began, Allen got to the ball park every day in time for the first pitch. Paying his way into the grandstand, he positioned himself in the upper deck near the press box where he one day hoped to work.

Readers of the Cincinnati Enquirer soon noticed that Jack Ryder’s “Notes of the Game” column often included an exact tally of how many balls and strikes each pitcher had thrown. Ryder was a good reporter, but these data were supplied by Allen, who charted every pitch while munching on a steady supply of food from the concession stand. Later he earned seventy-five cents a game for telephoning out-of-town scores from the Western Union ticker in the press box to the scoreboard. “I lost money on that deal,” Allen remembered, “I used to spend about a $1.50 a day for ice cream, soda, and peanuts.”

After graduation, Allen matriculated in psychology at Kenyon College in the same class as Bill Veeck. He covered baseball for the campus daily but in truth didn’t know what occupation to pursue. In 1935 he somehow managed to tour the Soviet Union with newsman H.V. Kaltenborn and was far out of touch with baseball until reaching Moscow where Ambassador William Bullitt let him read back copies of the New York Times.

After Kenyon, Allen enrolled in the Columbia University School of Journalism. But after little more than one semester, he was invited to join the Reds as a paid assistant to Gabe Paul, then the team’s publicity director and road secretary. Allen stayed with the Reds as they won consecutive National League pennants in 1939 and 1940. When the United States entered World War II, Allen was rejected for military service because of high blood pressure. In 1942, he took a civilian post with the navy and was shipped out of Seattle to work as a laborer on Kodiak Island, Alaska. After a year or so, he returned to Cincinnati to replace Paul, who had been called to the service.

All the while, Allen was accumulating the foundation of an outstanding collection of baseball books, manuscripts, and notes. As he recalled later, “a book — The Baseball Cyclopedia by Ernest J. Lanigan — got me started. I always loved baseball, but I wasn’t very good at playing the game. I wasn’t fast enough. But I still wanted to be a part of it and this was a way I could do it.” He began to build a variegated career as a baseball researcher, putting in stints for two Cincinnati newspapers, appearing on radio and later television and even working a year for The Sporting News. “It was my observation of Taylor Spink,” he said “that taught me the only real happiness is in one’s work.”

Still, as many baseball researchers have learned, breaking into print for profit requires not only talent but also luck. “You just can’t get out of college and say, ‘I’m a writer; hire me,’” Allen once reminisced. While working with the Reds he saw that G.P. Putnam’s Sons had begun publishing its series of club histories. He wrote to them cold, “and a fellow wrote back saying they didn’t know anything about me as a writer and that they hadn’t decided who they would assign the Reds book to.” Putnam told him to take a stab at it. “I wrote the book, they accepted it, and it got me started.”

That first book, The Cincinnati Reds (1948), led in turn to 100 Years of Baseball (1950) and The Hot Stove League (1955), an absolutely marvelous collection of unusual research and anecdotes, many of which eventually made their way into anthologies. These books established Allen as a recognized expert who could make a living from his passion. On Cincinnati’s radio station WSAI, for example, he once challenged listeners to write in — this was before talk shows — giving the names of former players for him to identify. On May 23, 1952, while working in Philadelphia, Allen and Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer engaged in a “Baseball Talkathon” from 11:15 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. on KYW. The pair answered questions telephoned to several operators and forwarded to moderator Jean Shepherd.

In early 1959, the National Baseball Hall of Fame announced that Allen would replace retiring Ernest J. Lanigan as historian. It was a propitious appointment for both the Hall and Allen who brought with him to Cooperstown not only his knowledge and research skills, but also a vast baseball library. The mover who trucked the books from Cincinnati said they filled fifty-five cartons and weighed 5000 pounds. Allen, who began his new job with no advance instructions, had a firm idea of how he would proceed. “I hope to make the office of Historian of the Hall a place where anyone may write for information about almost any phase of baseball history and receive accurate replies.”

The Allen family — Lee had married Adele Felix the previous August — settled into Cooperstown just a few months before the birth of twins Randall and Roxann in October 1959. The new father nevertheless dove into his work with a great deal of gusto. Ensconced in the old library on the second floor of the museum, Allen established a daily routine that included meeting a steady stream of visitors, answering mail as soon as it arrived, and chipping away at the long-range research projects he set for himself. His workdays soon stretched to twelve hours and his weeks to seven days.

One of these assignments involved uncovering the date and place of death for nineteenth century National Leaguers. Another had him breaking down the number of games outfielders had played in left, center, and right fields. “No one has ever separated outfields before,” Allen told Sports Illustrated shortly after he began. “When Zack Wheat is inducted into the Hall of Fame this summer, I’ll be able to tell him how many games he played in each field.”

Allen’s major effort was to collect biographical data on the 11,000 men he estimated had played in the major leagues to that point. In this mammoth task that would grow into the first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia, he labored with other pioneers in baseball research, including John Tattersall, S. C. Thompson, Frank Marcellus, Karl Wingler, Harry Simmons, Allen Lewis, Joseph Overfield, Clifford Kachline, and Paul Rickart.

After a while, the Allens decided to spend the summers in Cooperstown and the winters in Boca Raton, Florida. Allen used the trips back and forth as opportunities for extended research odysseys. He would visit one remote hamlet after another, prowl through graveyards and courthouse records, and gently pump as many townspeople as necessary for the information he was seeking.

Allen did not sit on his research. He turned it into a long list of articles, innumerable speeches to dozens of groups, and a series of books renowned for their original insights. In The National League: The Official History (1961), for example, he used his unprecedented access to league documents and correspondence to throw new light on pivotal events such as Fred Merkle’s “boner” and Hal Chase’s involvement in fixing games.

In the companion volume, The American League Story (1962), Allen related how president Ban Johnson moved the Milwaukee franchise to St. Louis, home of The Sporting News, and how in 1903, type for the peace agreement between the leagues was set in that newspaper’s composing room.

Basking in the success of these books, Allen accepted an additional commission, a column in The Sporting News. “Cooperstown Corner” ran from April 4, 1962, to May 31, 1969, a total of 133 times. It began as a biweekly feature whose regular appearance was sometimes delayed for lack of space. After August 24, 1963, it was printed much more sporadically: twice during the rest of that year, nine times in 1964, six in 1965, and not at all in 1966. In June 1967, the column resumed a biweekly schedule. It proved to be so popular that it became a weekly feature in February 1968, and remained so until Allen’s death. The last two columns appeared posthumously.

Simultaneously with the column, Allen wrote other books: a joint history of the Giants and the Dodgers, a collection of biographical sketches written with Tom Meany, lives of Babe Ruth and Dizzy Dean, and a history of the World Series published in 1969 as professional baseball observed its hundredth anniversary.

Surely, Allen must have looked forward to this centennial. For one thing, he now went to work in the new National Baseball Library, opened in 1968 as a separate building from the Hall of Fame. For another, the celebration commemorated events in his native city. He contributed a special essay on the Red Stockings of 1969 to The Sporting News and journeyed back to his hometown in May for a ceremony honoring Cincinnati players. After presenting a silver plate to Edd Roush as the greatest Red of all time and participating in the attendant festivities, Allen climbed into his car for the long drive back to Cooperstown.

When he reached Syracuse on the morning of May 20, he stopped and called a cab, complaining of chest pains. Two hours later, at St. Joseph’s Hospital, he was dead of a massive heart attack. If the truth be told, Allen had not been a well man. Undoubtedly, he worked far too long and too hard, ate, drank, and smoked too much, and had probably suffered an earlier heart attack several years before. Still, his death was a shock to the baseball world that had come to treasure him.

Sources

A version of this article was originally published as the Introduction to Cooperstown Corner (SABR, 1990), a collection of Allen’s columns that had run in The Sporting News in the 1960s.

In compiling this piece, the author mainly used Allen’s clipping files in the archives of The Sporting News in St. Louis (where the author works). He also spoke with Lowell Reidenbaugh, who was Allen’s contact with The Sporting News and remained on staff with the paper for many years afterwards.

Full Name

Leland Gaither Allen

Born

January 12, 1915 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

May 20, 1969 at Syracuse, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.