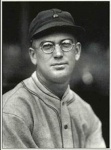

Lee Meadows

When 20-year-old right-hander Lee Meadows took the mound on April 19, 1915, for the St. Louis Cardinals, he became the first big-league ballplayer to wear spectacles since pitcher Will White of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in the American Association retired in 1886. The thought of a professional baseball player with “cheaters” was preposterous to most players, coaches, scouts, and fans at the time. Meadows was “regarded as a piece of comedy because he wore glasses,” reported Baseball Magazine in 1915.1 But Meadows was anything but a circus show. “[He] braved the jeers, the taunts, and the sneers to establish himself as the first bespectacled player,” reported Ford Sawyer.2 Over a 13-year period (1915-1927), Meadows was one of the most consistent workhorses in the NL, averaging 14 wins and 242 innings per season. Traded by the lowly Philadelphia Phillies to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1923, Meadows helped anchor a strong staff that enabled the Bucs to capture the World Series championship in 1925 and another pennant two years later.

When 20-year-old right-hander Lee Meadows took the mound on April 19, 1915, for the St. Louis Cardinals, he became the first big-league ballplayer to wear spectacles since pitcher Will White of the Cincinnati Red Stockings in the American Association retired in 1886. The thought of a professional baseball player with “cheaters” was preposterous to most players, coaches, scouts, and fans at the time. Meadows was “regarded as a piece of comedy because he wore glasses,” reported Baseball Magazine in 1915.1 But Meadows was anything but a circus show. “[He] braved the jeers, the taunts, and the sneers to establish himself as the first bespectacled player,” reported Ford Sawyer.2 Over a 13-year period (1915-1927), Meadows was one of the most consistent workhorses in the NL, averaging 14 wins and 242 innings per season. Traded by the lowly Philadelphia Phillies to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1923, Meadows helped anchor a strong staff that enabled the Bucs to capture the World Series championship in 1925 and another pennant two years later.

Henry Lee Meadows was born on July 12, 1894, in Oxford, a small town in the heart of North Carolina’s tobacco county, about 30 miles northeast of Durham. His parents were John M. Meadows, a tobacco buyer, and Cora Henderson (Goss) Meadows, both native North Carolinians of English descent. They had four children, Lillie, Henry (as Lee was called as a child), Hallie May, and Susie. Lee attended Oxford elementary school and Horner Military Academy beginning in the eighth grade. By all accounts, the tall and slender Meadows was a natural athlete. He was a good swimmer, played football, and ran track at school;3 however, it was on the diamond that he dazzled as a hard-throwing twirler.

At the age of 17, Meadows signed a professional contract with the Morristown (Tennessee) Jobbers in the Class D Appalachian League in 1912, but he soon had second thoughts about playing more than 300 miles from home and did not report. He resumed pitching for semipro teams near Oxford,4 and returned to the military academy for his final year of study. In the meantime, W.G. Bramham, president of the Durham Bulls of the Class D North Carolina State League (and later president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues) had purchased his contract for $25.5 Meadows, while hurling for his school team in the spring of 1913, impressed Bulls manager Jim Kelly in an exhibition game against his club. Kelly added the teenager to his roster, and the youngster’s professional baseball career began again. “Specs,” as newspapers had been calling him since his high-school days, set the league on fire, going 21-14 in a 114-game season, and 19-12 in 1914.

By early 1914 Meadows had begun attracting big-league scouts who, according to Sid C. Keener of the St. Louis Times, had heard about the hurler’s “iron man feats, pitching double headers, and curving every other day.”6 But the reaction of most scouts upon seeing the only player with glasses in Organized Baseball was one of disbelief, disdain, and outright laughter despite Meadows’ accomplishments. Bob Connery, scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, was an exception and was willing to take a chance. On his recommendation, the Redbirds signed Meadows in July 1914, and announced the ground-breaking signing the following month.7 The New York Giants, Brooklyn Superbas, and Philadelphia Athletics were also interested in acquiring Meadows.8

Meadows made an unusual jump from Class D to the big leagues when he joined the Cardinals at spring training in Hot Wells, Texas, in 1915. His spectacles “give him an entirely different appearance from the average ball player,” wrote J.C. Kofoed, but player-manager Miller Huggins and especially catcher Frank Snyder were impressed with the 6-foot, 165-pounder.9 After tossing three-hit ball over 5? shutout innings against the Cincinnati Reds in his debut, Meadows made his first start four days later, and picked up his first of 188 big-league victories. Described as the “best twirler on the Cardinals staff,” Meadows tossed his only career one-hitter, on July 2, when he blanked the Reds at Redland Field to record his first of 25 shutouts.10 “[Meadows] taught the baseball world that a pitcher with weak eyes may yet win renown in the Major Leagues,” wrote Ward Mason in Baseball Magazine.11 For a sixth-place club, Meadows posted a 13-11 record, made 26 starts among his 39 appearances, and carved out a 2.99 ERA in 244 innings.

Given his glasses and success in his rookie season, the 20-year-old Meadows was among the most talked-about players in the offseason. His spectacles lent him an air of intellectuality, class, and maturity in comparison to the often rowdy, hard-living ballplayers of the era. The Sporting News capitalized on Meadows’ popularity by publishing his serial novel, Cutting the Corners, about baseball players’ lives. “Few men who have taken up baseball as a profession, or as a stepping stone, are as versed as Meadows,” opined the weekly.12 Meadows became the poster child, indeed inspiration, for all “Four-Eyes” (as he was often described) who wanted to play sports. “I have worn glasses ever since I was six years old,” he told sportswriter Ward Mason, “and ever since I can remember I wanted to be a professional ball player.”13 For the rest of his professional baseball career, Meadows’ name was rarely mentioned without reference to his glasses.

While the Cardinals dropped to seventh place in 1916 with a record of 63-90, Meadows emerged as one of the most dependable rubber-armed hurlers in baseball. Described as a pitcher with “rare promise” and a “good reputation,” Meadows led the NL with 51 appearances, including 36 starts, logged 289 innings, and posted a 2.58 ERA.14 “Meadows is a noodle pitcher,” said skipper Miller Huggins. “He uses his head.”15 But the 12-game winner’s cerebral approach to the game could not compensate for the NL’s lowest-scoring team. Meadows was a hard-luck loser, as the Redbirds scored two runs or less in 15 of his NL-most 23 losses.

One game Meadows did not lose was on March 8, 1917, when he married Catherine “Carrie” Woodworth, originally from Virginia. The couple had two children. Blessed with good looks, gray eyes, and dark hair, Meadows had a reserved personality and was not prone to make the headlines. Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger described him as “one of the finest characters that ever walked to a rubber.”16 Companies recognized this trait, as well, and hired him as a pitchman in national advertising campaigns for Lucky Strike cigarettes and Magic liniment, among others.

At this stage of his career, Meadows relied on his curve, fastball, and a spitball. “[W]atch him throw a curve which breaks so sharply a few feet in front of the plate that causes the swatter to miss it half a foot; see him hook a fastball that jumps on the inside and then see a spitter shoot in all directions,” wrote Sid Keener.17 Pitching in an era when strikeouts were uncommon, Meadows was known for his “great speed,” though he averaged only three whiffs per nine innings in his career. Meadows had a submarine-to-sidearm delivery and could throw all three pitches from the same angle; his pitching motion was often compared to Grover Cleveland Alexander’s.18

Despite being considered a “holdout” and reporting late to the Cardinals’ camp in 1917, Meadows teamed with righty Bill Doak to lead St. Louis to a third-place finish and 82 wins, the club’s most since 1899, when it was known as the Perfectos.19 Meadows went 15-9, logged 265? innings, and posted a 3.08 ERA, which in the context of the Deadball Era was high (the league average was 2.70). In a showdown with the Boston Braves’ Art Nehf on September 22 at St. Louis’s Robison Field, Meadows hurled arguably the best game of his career, only to come away with a no-decision; however, in an interesting twist, he was credited with a shutout. Meadows whiffed 10 batters in 14 innings (both career bests) and did not yield a run; Nehf also threw 14 scoreless innings before the game was called because of darkness.

“A complete failure,” wrote sportswriter W.A. Phelon of Meadows’s 1918 season, shortened by 25 games because of World War I.20 The North Carolinian unexpectedly slumped to 8-14 for the cellar-dwelling Cardinals and his ERA (3.59) was the third highest in the NL. Exempted from the draft because of his eyesight and his dependent wife and child, Meadows lived in North Carolina in the offseason.

Meadows was involved in an automobile accident a week before the season opened in 1919.21 Apparently feeling the effects of crashing into a trolley car in St. Louis, Meadows struggled for first-year skipper Branch Rickey (who also served as GM), losing his first six decisions, and was ultimately relegated to the bullpen in July. On July 14 the Redbirds sent Meadows and utilityman Gene Paulette to the Philadelphia Phillies for hurlers Elmer Jacobs and Frank Woodward and utiltyman Doug Baird. Based on statistics alone, the trade seems like a rare mistake by Rickey. Jacobs and Woodward won a combined 10 games and lost 19 in their short tenure with St. Louis, and Baird suited up for just 202 games. Meadows, on the other hand, regained his form and completed 15 of his 17 starts with the Phillies in 2½ months. However, it appears as though Rickey wanted to purge Paulette, whose association with gamblers in St. Louis was, according to SABR’s Bill Lamb, known to both teams.22 Involved in a game-fixing scandal in 1919, Paulette became the first player permanently banned by Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, on March 24, 1921.

After his trade to the Phillies, Meadows emerged as the ace on the NL’s worst staff. In his first start, he avenged his trade by tossing a 12-inning four-hitter to defeat the Cardinals at the Baker Bowl on July 17. He won his first six decisions, but managed just two more victories in his next 12 decisions to finish with a combined record of 12 wins and a league-worst 20 losses despite a robust 2.59 ERA in 250? innings. His final loss (a complete-game 13-hitter to Jesse Barnes and the New York Giants, 6-1 at the Polo Grounds on September 28) was completed in just 51 minutes to set a big-league record as the fastest nine-inning game in history. Barring unforeseen measures by Major League Baseball to speed up the game, this record will never be broken.

In the decades before plastic lenses became commonplace for athletes, many feared that a player could be permanently disabled should he be hit in the eye with a ball. That fear resurfaced on May 13, 1920, when Meadows hit a foul tip during batting practice that shattered his glasses. Following reports that particles of glass had penetrated Meadows’ eyes, The Sporting News, wrote that the injury “probably will end [his] playing days.”23 Meadows recuperated at his home in North Carolina, and made a spectacular return less than three weeks later by tossing a complete game to improve his record to 5-0. “Specs” was one of the few bright spots for the league’s worst team. He paced the club with 16 victories (14 losses) and a 2.84 ERA, completed 19 starts, and logged 247 innings. The highlight of his season may have been on August 31 when he tossed a five-hit shutout to defeat the Chicago Cubs and pitcher Pete Alexander, whom Philadelphia had traded after the 1917 season, thereby ushering in a stretch during which the Phillies posted losing records in 29 of the next 30 seasons, including 16 last-place finishes.

Meadows’ career entered a new phase in 1921 when Major League Baseball banned the use of the spitball for all but 17 pitchers who had been given an exemption. Deprived of one of his three primary pitches, Meadows developed a “fadeway delivery” (a screwball) that was compared to Christy Mathewson’s.24 His transformation was anything but easy, complicated by a season-long nerve pain in his right shoulder that forced him to miss about five weeks of the season.25 Nonetheless, on a terrible staff, described by beat reporter James C. Isaminger as “weak as bread,” Meadows notched a team-high 11 wins in the emerging era of high-scoring games marked by the rise of the home run (which increased from 261 in 1920 to 460 in 192126). For the cellar-dwelling Phillies, Meadows (11-16), was joined by Jimmy Ring (10-19), George Smith (4-20), and Bill Hubbell (9-16) to commiserate over the club’s 103 losses.

Lauded as the Phillies’ “whole pitching staff,” Meadows continued to be plagued by his shoulder for much of the 1922 campaign while rumors swirled for a second season about his eventual trade by the perpetually cash-strapped club.27 Just 27 years old, Meadows tossed a complete-game four-hitter to defeat the Boston Braves, 7-1, on Opening Day, en route to a 12-18 record and a respectable 4.03 ERA in 237 innings. All pitchers, and not just lefties, were worn down psychologically hurling for woeful teams in the cramped Baker Bowl, with its short, 280-foot right-field wall and shallow, 300-foot right-center-field power alley; however, Meadows trudged on and earned the respect of opposing managers and players. “Wise in the art of pitching, a good student of human nature, fighting valiantly for a lost cause,” read one description of Meadows’ approach to the game.28

Meadows’ career spanned the last years of the Deadball Era and the advent of a new offensive game that required pitchers to adjust and learn essentially new tactics. The North Carolinian was acutely aware of this evolution and its ramifications for his career. “Pitching has changed in the last few years, and the ball has something to do with it,” he said in 1923. “The rule makers put a ban on a pitcher putting any foreign substance on a sphere or cutting or grinding the cover. With the ban in effect, the ball wouldn’t curve or sail as well as it used to.”29 While his ailing shoulder diminished the effectiveness of his fastball, Meadows never fully mastered the screwball, rendering him primarily a curveballer. But he also recognized that he had to modify his curveball, which he threw at different angles and speeds. “It used to be that no more than four or five balls were used in a single game. Now a new ball is thrown out any time one is fouled. That means that [a pitcher] can’t throw as sharp a curve as he could with a used ball.”30

Heading into the 1923 season, Philadelphia sportswriter James C. Isaminger admitted that Meadows’ “arm is not as strong as it used to be.” “[There] is no quit in this man’s make-up,” continued the reporter in an attempt to quash rumors that Meadows (who surrendered 53 hits and 29 earned runs in 25? innings over his last five starts in 1922) had “laid down.”31 Meadows’ nightmare continued into the 1923 season. Following a horrendous start (a 13.27 ERA and 40 hits in 19? innings), Meadows was shipped along with infielder Johnny Rawlings to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Whitney Glazner, infielder Cotton Tierney, and an estimated $50,000 on May 23. Pirates beat reporter Ralph S. Davis called that trade a “surprise” while papers in Pittsburgh generally panned the deal for a player with a supposed lame arm.32

Not only did Meadows arrive on a pennant-contending club, he was paired with manager Bill McKechnie, regarded as one of the finest handlers of pitchers of the era. Meadows pitched a complete game to defeat the Chicago Cubs, 2-1, in his debut with the Bucs, on May 27, despite giving up 15 hits. The outing was indicative of Meadows’ philosophy of pitching. “I go out and pitch with the idea that each hitter is entitled to one hit, and that I can win if I hold the team to nine hits. So I pitch consistently to a man’s weakness, and do not switch if he hits.”33 Defying expectations, Meadows excelled for the Pirates. On September 15 he needed just 78 minutes to push his record to 15-7 since the trade by tossing a complete game, defeating the Brooklyn Robins, 4-1, in the first game of a doubleheader. More importantly, the victory moved the Pirates to within four games of the league-leading New York Giants; however, the Bucs slumped thereafter, losing seven of eight games to finish in third place. Meadows posted a 16-10 record with Pittsburgh, completed 17 of 25 starts, and carved out a team-low 3.01 ERA.

“Old ‘Four Eyes’ … has taken a new lease on life since his sentence to penal servitude with the Phillies has been commuted,” wrote the Brooklyn Eagle as the 1924 season commenced.34 Meadows proved that his arm was strong by completing six of his first eight starts of the season and logged at least 10 innings three times, yet was just 3-4 despite a 2.60 ERA. Widely considered a threat to end the New York Giants’ three-year hold on the pennant, the Pirates played .500 ball through early July and were 11½ games off the pace on July 23 before winning 33 of 44 games to engage the Giants and the Brooklyn Robins in a exciting pennant race in September. In the second game of a doubleheader on September 18, Meadows won his sixth straight decision by hurling a complete game to defeat Philadelphia and keep the club just 2½ games back. But a week later the Pirates’ pennant aspirations were doomed when they were swept by the Giants in a three-game series at the Polo Grounds, and finished in third place. In an erratic season, Meadows won 13 of 25 decisions with a 3.26 ERA in 229? innings.

Meadows got off to a blistering start in 1925 as the Pirates were once again in a heated battle with the Giants. “The bespectacled veteran is having one of the best seasons of his career,” wrote beat reporter Ralph S. Davis as Meadows improved his record to 11-3 on June 25 with a complete-game victory over the St. Louis Cardinals.35 “[Meadows] is much respected by every club that opposes him, for he is a clever handler of the ball, knows the weak point of opposing batters, and has been getting results,” continued Davis. In and out of first place in July, Pittsburgh took the top spot on August 3 and captured its first pennant since 1909.

Meadows may have “carried the team,” according to Davis, but the Pirates staff was exceptionally consistent.36 The North Carolinian led the team in most categories, including wins (19), innings (255?), starts (31), and complete games (20), and was joined by four other hurlers who logged at least 200 innings: Vic Aldridge (15-7), Ray Kremer (17-8), Johnny Morrison (17-14), and Emil Yde (17-9).

McKechnie tabbed “slab ace” Meadows, who had pitched only one inning since September 16, to start Game One of the World Series against the reigning champion Washington Senators, on October 7 at Forbes Field.37 In a “courageous” duel, Meadows tossed six-hit ball over eight innings, yielding three runs, in a 4-1 defeat at the hands of Walter Johnson who whiffed 10 and gave up just five hits.38 Newspapers in Pittsburgh reported after the game that Meadows had hurt his right shoulder. McKechnie attempted to play down the rumors, but Meadows did not pitch again in the Series, which saw the Pirates erase a three-games-to-one deficit to capture the title in stunning fashion.

As the 1926 season got under way, Meadows’ right shoulder seemed healthy, but the 31-year-old suffered from a severe sinus infection for most of April, May, and June.39 Despite the affliction, he won his first eight decisions of the season, capped off by a complete-game six-hitter to beat the Cardinals, 2-1, on June 22 to keep Pittsburgh a half-game behind the upstart Cincinnati Reds in the pennant race. But the inconsistent Pirates had fallen to third place, six games off the lead, by the end of June before they surged, winning 27 of their next 41 games. On August 10 Meadows tossed a complete-game eight-hitter to subdue Brooklyn at Ebbets Field, 10-2, improving his record to 15-4 and keeping the streaking Bucs in the driver’s seat of the pennant race with a season-high three-game lead over the Cardinals. While the Pirates faded in September (13-17) and finished in third place, St. Louis captured its first NL pennant. Aiming for his 20th victory on the last day of the season, Meadows enjoyed a nine-run cushion against the Boston Braves after four innings before yielding six runs and departing after 4? innings. A generous official scorer credited Meadows with the win to enable the respected pitcher to tie teammate Ray Kremer, Cincinnati’s Pete Donahue, and St. Louis’s Flint Rehm for the league’s lead in victories. Meadows completed 15 of 31 starts, while his 3.97 ERA in 226? innings was higher than the league average (3.82).

In 1927 Meadows got off to another fast start, winning his first seven decisions and improving his record to 10-1 by tossing his second consecutive shutout, on June 20. Locked in a pennant race with the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals for most of the season, the Pirates fell six games off the lead on August 16, before they surged. Meadows’ complete game, 4-3 victory over the Cubs at Forbes Field on September 1 pushed the Bucs into a tie with Chicago in first place. Pittsburgh took sole possession of the lead the following day when Ray Kremer defeated Pete Alexander and the St. Louis Cardinals, and finished the season with a 94-60 record to capture its second pennant in three years. Often pitching out of turn and on three days’ rest for first-year skipper Donie Bush, Meadows won 19 games and was the workhorse of the staff, leading the league with career highs in starts (38) and complete games (25). He also logged a career-best 299? innings and posted a robust 3.40 ERA. While the Pirates were the NL’s highest-scoring offense, they often went silent when Meadows hurled. In eight of his 10 losses Pittsburgh scored two runs or less. In an interesting twist, Meadows’ roommate was Carmen Hill, who had become the second big-league pitcher to don spectacles when he debuted with the Pirates in August 1915. A journeyman righty with just nine big-league wins up to that season, “Specs” Hill led the Bucs with 22 wins.

Pittsburgh’s reward for winning the pennant was a World Series matchup with one of the greatest teams in baseball history, the heavily favored New York Yankees. Facing Hall of Famer Herb Pennock in Game Three at Yankee Stadium, Meadows yielded seven runs and seven hits in 6? innings and an eventual 8-1 loss. The Bronx Bombers completed the Series sweep the next game.

After he won 58 games in the previous three years, Meadows’ career came to an abrupt and unexpected end. In spring training, the 33-year-old came down with an “ailing arm” and had a recurrence of “sinus troubles.”40 He made only four appearances, surrendering 18 hits and 9 earned runs in 10 innings before being placed on the “voluntary retirement list” in late August.41 He attempted a comeback in 1929, but made only one relief appearance and hurled in several exhibition games before the Pirates optioned him to the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association. He finished the season with the Newark Bears in the International League and went a combined 3-12. Like many hurlers of his era, Meadows took an ignominious journey through the low minors (hurling for the Class A Dallas Steers in the Texas League and the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association in 1930 and 1931), before coming full cycle with a two-game comeback with the Durham Bulls in 1932.

Meadows was considered a star and among the best pitchers of his era, but his accomplishments on the diamond have largely been forgotten and confined to history. He posted a 188-180 record, accompanied by a 3.37 ERA in 3,160? innings, but will forever been known as the answer to the trivia question about the first modern baseball player to wear glasses.

Following his retirement in 1932, Meadows returned to Leesburg in southern Florida, where he and his family had established residence a few years earlier. He returned to Organized Baseball in 1937 to manage the Leesburg Gondoliers in the Class D Florida State League, and briefly piloted the DeLand Red Hats in the same league two years later. By 1940 the family resided in Daytona Beach, Florida, where Lee was employed as a deputy clerk with the IRS until his retirement in 1951.

On January 29, 1963, Meadows died at the age of 68 in Daytona Beach as a result of multiple cerebral emboli cause by heart disease. He was buried at the Resthaven Garden of Memories in Decatur, Georgia.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, the author consulted:

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

SABR.org.

Lee Meadows player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 “Baseball Briefs,” Baseball Magazine, October, 1915, 52.

2 Ford Sawyer, “Taking Away His Spitball Didn’t Disable Meadows.” [Undated article from player’s Hall of Fame file].

3 “Pitcher Wearing Glasses Is Prize,” Pittsburgh Press, May 10, 1915, 22.

4 Sawyer.

5 L.H. Addington, “Judge Branham to the Rescue,” Baseball Magazine, July, 1937, 370.

6 Sid C. Keener, “Pitcher With Glasses a Prize. Hug Fancies Recruit Meadows,” St. Louis Times. [Undated article in player’s Hall of Fame file].

7 “Lee Meadows Sold to Cards,” Charlotte (North Carolina) News, August 7, 1914, 6.

8 Ibid.

9 J.C. Kofoed, “New Stars of 1915,” Baseball Magazine, October 15, 42.

10 Kofoed.

11 Ward Mason, “An Eyeglassed Athlete,” Baseball Magazine, March 1916, 78.

12 The Sporting News, December 9, 1915, 7.

13 Mason.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 The Sporting News, August 30, 1923, 1.

17 Keener.

18 Keener.

19 Sporting Life, March 10, 1917, 4.

20 W.A. Phelon, “Who Will Win the Big League Pennants,” Baseball Magazine, October 1919.

21 News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina), April 19, 1919, 3.

22 Bill Lamb, “Gene Paulette,” SABR BioProject.

23 The Sporting News, May 27, 1920, 4.

24 Winston-Salem (North Carolina) Journal, March 15, 1922, 6.

25 “Phils Hurlers a Little Slow,” Charlotte Observer, March 24, 1922, 12.

26 The Sporting News, April 14, 1921, 1.

27 Don Doherty, United Press, “Phillies Cannot Be Disappointment This Year Even If They Make Last Place,” The Republican and Times (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), April 8, 1922, 4.

28 “Made in Carolina Product Going Great Guns In the Big Show,” High Point (North Carolina) Enterprise, July 18, 1922, 5.

29 The Sporting News, May 3, 1923, 4.

30 Ibid.

31 The Sporting News, January 4, 1923, 1.

32 The Sporting News, May 31, 1923, 3.

33 Joe King, “Want to Argue with Pie Traynor?” [Unattributed article in player’s file, dated 1952].

34 “If Babe Adams Can Stand Gaff Pittsburgh May Win Right To Meet Yankees,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 7, 1924, A3.

35 The Sporting News, July 6, 1925, 3.

36 The Sporting News, June 3, 1926, 1.

37 The Sporting News, July 6, 1925, 3.

38 Associated Press,“Pirates Defeated in Opening Battle,” Oregon Statesman (Salem), October 8, 1925, 1.

39 The Sporting News, June 3, 1926, 1.

40 The Sporting News, March 22, 1928, 3 and July 19, 1928, 3.

41 Associated Press,“Lee Meadows To Return in Spring,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, September 4, 1928, 9.

Full Name

Henry Lee Meadows

Born

July 12, 1894 at Oxford, NC (USA)

Died

January 29, 1963 at Daytona Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.