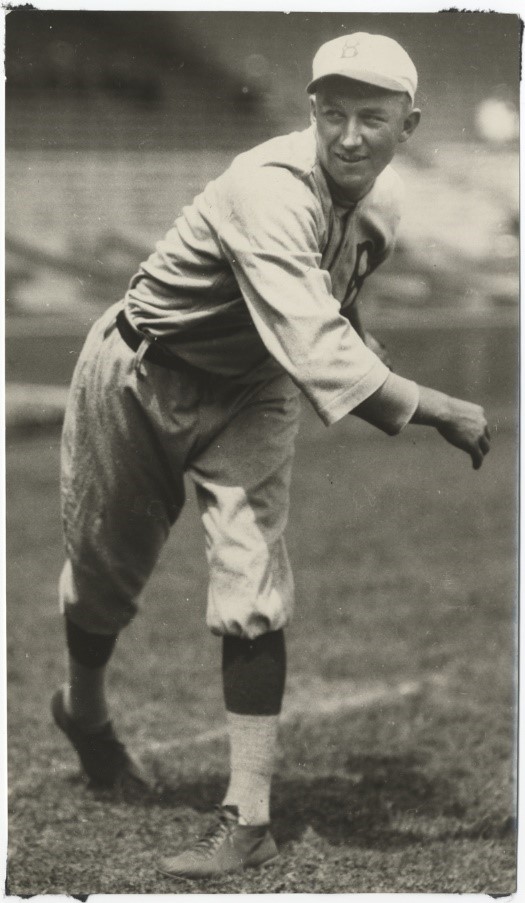

Leon Cadore

In the age of 100-pitch limits and “five and fly” starters, this sounds like a video game gone haywire: Leon Cadore and Joe Oeschger each pitched 26 innings on May 1, 1920, completing the longest game in major-league history.

In the age of 100-pitch limits and “five and fly” starters, this sounds like a video game gone haywire: Leon Cadore and Joe Oeschger each pitched 26 innings on May 1, 1920, completing the longest game in major-league history.

Cadore was a Brooklyn favorite who spent his childhood in the borough and earned respect for his combat service in World War I. A popular teammate, “Caddy” entertained with card tricks and other sleight of hand while using those same skills on the mound. The right-hander knew all the tricks for doctoring a baseball. His pal Casey Stengel said Cadore could scuff a ball with one hand by cutting it with his thumbnail.

He provided the prop for one of Stengel’s most famous stunts. Stengel, playing for Pittsburgh, butchered a fly ball and let in three Brooklyn runs. The Ebbets Field fans hooted at him, but it was all in fun; he had been a popular Dodger.1 Later in the game, Cadore, sitting in the Brooklyn bullpen, caught a tiny sparrow. He handed it over to Stengel, who stashed it under his cap. When he came to bat, with the crowd still razzing him, Casey tipped his cap and gave the fans the bird.2

Cadore kept his teammates laughing at his get-rich-quick schemes. One brainstorm was instant whiskey, powdered like instant coffee. His love of money was exceeded by his love of spending it. “To Caddy, money was something to get rid of, like a bad headache,” sportswriter Eddie Murphy remembered.3

Leon Joseph Cadore was born in Chicago on November 20, 1891, the first of three children of the former Georgianna Jeannot and George Cadore. The family moved to Brooklyn when Leon was a baby, and his father worked as a telegraph operator on Wall Street. After Georgianna Cadore died young, her only son was sent to live with relatives in Idaho and Washington.

At 13, Leon enrolled in a prep-school program at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, and played varsity baseball, basketball, and football in his final year at the age of 16. He was elected to Gonzaga’s athletic hall of fame.4 He is reported to have attended Stanford, but the university has no record of him.5 In summers he pitched semipro ball in Idaho and Montana, earning up to $100 a game.

Cadore rejoined his father in Brooklyn in 1911 and soon signed a professional contract with the International League’s Jersey City club. He was farmed out to Class-B Wilkes-Barre, where he spent most of the next three years. After a 20-win season in 1914, he was drafted by the Dodgers. Brooklyn gave him brief trials in 1915 and 1916, but he pitched primarily at Double-A Montreal. He went 25-14 in his second year with the Royals and stuck with the Dodgers in 1917.

Five days before Opening Day, the United States declared war on Germany. A pall of uncertainty hung over the baseball season. In July The Sporting News reported that Cadore was likely to be among the first players called up in the military draft. As it turned out, few major leaguers were drafted in that first wartime season. It was “baseball as usual,” except that players conducted make-believe military drills shouldering bats instead of rifles.6

The Dodgers, defending National League champions, collapsed to seventh place. The 25-year-old rookie Cadore was one of the few bright spots. At 6-feet-1 and nearly 200 pounds, he fit the mold of the big, strong pitchers that manager Wilbert Robinson liked. “[H]e really has all the earmarks of a great pitcher,” Robinson said.7 Cadore finished 13-13 for the losing club, but his 2.45 ERA was 14 percent better than average.

Despite his size, Cadore was not a power pitcher. The Brooklyn Eagle’s Tommy Rice described him as “a smart pitcher, with reasonable speed and a variegated delivery.”8 He relied primarily on curves, changing speeds, and excellent control. He may have mixed in a few scuffballs as well.

The draft caught up with Cadore soon after the season ended. The Army sent him to officer training school at Camp Gordon, Georgia. He rejoined the Dodgers temporarily in June 1918 while in Brooklyn on furlough. On June 5 he shut out the Cardinals on four hits. Four days later he held Pittsburgh to two hits and one run in eight innings before he left the game with no decision. He spent some time with his buddy Stengel, and Cadore’s stories of Army life may have persuaded Stengel to enlist in the Navy.

Lieutenant Cadore was one of the white officers assigned to command a “colored” unit, the 369th Infantry Regiment. After landing in France, the regiment saw hard combat in the final weeks of the war. The 369th, nicknamed “the Harlem Hellfighters,” captured a reported 1,000 German troops the day before the November 11 armistice ended the fighting. The French government awarded the unit the Croix de Guerre for its service in defense of the nation.

“At the time, many Americans, including military leaders, believed African Americans lacked the intelligence and courage to fight,” said Barbara Lewis Burger of the US National Archives.9 The Hellfighters proved the racists wrong. In a letter home, Cadore wrote, “Every man in my regiment fought with the courage of a lion.”10

Cadore brought back one favorite story from the war. He was belly-crawling under enemy fire when another soldier tugged at his arm and asked, “Aren’t you Leon Cadore? Sure, you remember me.”

“I wasn’t trying to remember any person,” Cadore said. “I was wondering if I was ever going to come out of this battle alive.”

“Sure, you remember me, Leon,” the soldier persisted. “I’m the guy who hit that triple off you when you were pitching for Gonzaga U in Spokane, Washington.”11

Cadore returned to Brooklyn in 1919 and joined the ranks of the National League’s elite pitchers. He finished in the top 10 in several categories. His adjusted ERA of 125 was the best of his career, although his record was 14-12 for the fifth-place Dodgers.

He opened the 1920 season with two complete-game victories, one an 11-inning shutout of the Boston Braves. When the Dodgers played in Boston on May 1, it was a rematch between starting pitchers Cadore and Joe Oeschger, another 28-year-old right-hander.

The day was raw and damp with off-and-on drizzle that held the Saturday crowd to no more than 4,500. Cadore walked the first man he faced, setting the tone for his afternoon. He allowed at least one base runner in each of the first nine innings on 11 hits and two walks. His fielders bailed him out. Left fielder Zack Wheat made a shoestring catch, second baseman Ivy Olson flagged down a scorching grounder to start a double play, and first baseman Ed Konetchy snared a pop foul while balancing on the dugout steps.

The Dodgers staked Cadore to a 1-0 lead in the fifth, but he gave the run back in the next inning. Then the teams settled into a stalemate as afternoon turned to gray, chilly evening.

Around the 20th inning, manager Robinson asked Cadore if he wanted relief. “If that fellow can go another inning, I can too,” the pitcher replied.12 Oeschger wasn’t about to beg off. “If a pitcher couldn’t go the distance, he soon found some other form of occupation,” he explained years later.13 As the game wore on, both men began limiting themselves to just one or two warmup tosses before each inning.

In the 25th the teams broke the major league record for the longest game, surpassing a 1906 contest between the Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Americans. Philadelphia’s Jack Coombs and Boston’s Joe Harris went all the way in that one.

After Oeschger allowed a run in the fifth, he pitched 21 scoreless innings, the last nine without allowing a hit. He was pumping fastballs one after another. Cadore, mixing “curves and slow stuff,”14 shut out Boston for the last 20 frames.

When Cadore retired the first two Braves in the 26th, he had set down 19 in a row. He gave up his 15th hit, a squibber off the bat handle of Boston’s Walter Holke, before getting the third out. Plate umpire Barry McCormick talked to both managers and at 6:50 p.m. decreed that it was too dark to continue. Official sunset was still an hour away, but batters were complaining that they couldn’t see the ball in the mist and heavy overcast. The game would have been stopped earlier except for a fluke of the calendar: it was the first day of Daylight Saving Time in Boston, pushing sundown an hour later.

“It was the hitters who were squawking to end it,” Oeschger recalled. “I certainly didn’t want it to stop and I don’t think Cadore did.”15 Cadore said, “[T]he chief thing that was bothering me was the fact that after working all those hours we still failed to win the game.”16

“All those hours”? The 26 innings took just three hours and 50 minutes — almost three complete games in under four hours. When the White Sox and Brewers played 25 innings in 1984, they took more than twice as long.

Cadore got a postgame rubdown for the first time in his life. Then he went back to his hotel and fell into bed. He stayed behind while his teammates returned to Brooklyn for a game the next day, because Sunday ball was not allowed in Boston.

Oeschger had completed a 20-inning game the year before and is the only man to reach that milestone twice. The feat was recognized as extraordinary and dangerous. Several writers predicted that the pitchers’ arms would be destroyed.

When the Braves and Dodgers resumed their series in Boston on Monday, Cadore asked Oeschger how he was feeling. “Me?” Oeschger replied. “I’ve been waiting to see how you feel. I’ve been waiting for you to make a move about quitting. We’ve ruined ourselves, you know.”17

Cadore said he couldn’t lift his arm to comb his hair for three days. Years afterward he estimated that he had thrown close to 300 pitches; Oeschger thought his total was around 250. Oeschger said his arm didn’t hurt any worse than after a normal start, but his body felt the strain. A few days later he pulled a leg muscle while running in the outfield and couldn’t pitch again for 11 days.

Cadore took a week off before his next start, when he was knocked out in the fifth inning. He rested another 11 days, then shut out defending NL champion Cincinnati.

“I think the game definitely did something to my arm,” Cadore said decades later. “I don’t think I ever had the same stuff again.”18 He was not the same pitcher after May 1. His adjusted ERAs in 1917 and 1919: 114 and 125, all-star level. In 1921 and 1922, 95 and 94 (100 is league average).19 Cadore accumulated 10.8 pitching WAR in 1917 and 1919, only 3.0 in 1921 and 1922, according to Baseball-Reference.com.

An anonymous Sporting News story said Cadore “did not amount to much” for the rest of the 1920 season,20 but that’s not true. He had enough left in the season’s final month to start six times in 17 days as the Dodgers were fighting for the pennant. On September 4 he shut out Boston to lift his club into first place. After two days’ rest, his second straight shutout launched a 10-game Brooklyn winning streak that all but wrapped up the championship. He went 4-2 with a 2.15 ERA down the stretch, hardly the work of a worn-out pitcher.

In Game One of the World Series against Cleveland, Cadore pinch-hit in the eighth inning — the first pinch-hit appearance of his career — and then pitched a 1-2-3 ninth. After the Indians won two of the first three, Robinson chose Cadore as the surprise starter in Game Four.

Cleveland leadoff man Charlie Jamieson ripped a line drive right back at him, and he caught it in self-defense. Then the Indians jumped on him for two singles, a walk, and a sacrifice fly to chase home two runs before he got the side out. When the first two batters in the second singled, Cadore was knocked out after facing just eight men. Robinson acknowledged he had played a hunch that Cadore could handle Cleveland’s left-handed hitters. “You are always a bum guesser when you pick a loser,” the manager said.21 Cleveland went on to win the best-of-nine Series in seven games.

The Indians won the crown, but Cadore got the girl. He had promised Helen Sweeney that he would marry her if the Dodgers won the pennant. He gave her a ring during the World Series and kept his promise to the 23-year-old secretary on November 20.22

Cadore’s career tailed off quickly over the next two years as the Dodgers fell back to the bottom half of the standings. His arm began hurting during the 1922 season, and Brooklyn put him on waivers in July 1923. After brief trials with the White Sox and Giants, his career ended when the Giants released him the following year.

And Joe Oeschger? He wasn’t ruined. He bounced back to post a career-best 20-14 record in 1921 and pitched in the majors until 1925. Then he played parts of two more years in the minors.

Cadore put his outgoing personality to work as a stockbroker in New York, a sure-fire way to get rich quick in the roaring market of the 1920s. Soon after his divorce from Helen in 1931, he married Maie Ebbets, a daughter of the late Dodgers owner. She was divorced and nine years older than her new husband.

With the stock market scraping bottom during the Depression, Cadore’s life spiraled downhill. He was arrested in 1935 when several clients accused him of stealing from their accounts. The state attorney general’s office said it had been investigating his activities for several months.23 The disposition of those charges could not be found.

The next year Cadore was struggling as a commission salesman for a drug company, and he and his wife were reported to be “living in virtual destitution in a $1-a-day furnished room.” Maie was one of the heirs to her father’s million-dollar fortune, including his 50 percent ownership of the Dodgers, but the estate was tied up in seemingly endless lawsuits. She said she had received no money from the team since 1931. “I am down to my last rags,” she told a reporter. “I have no clothes. We have nothing. I applied for home relief [welfare], but they laughed at me when I told them I was one of the Ebbets. I couldn’t make them believe I was destitute.”24

When the Ebbets executors sold the estate’s share of the Dodgers to Branch Rickey, Walter O’Malley, and pharmaceutical executive John L. Smith in 1945, the Cadores and other heirs sued unsuccessfully to block the deal. Like Dickens’ Jarndyce v. Jarndyce, litigation over the estate “drag[ged] its dreary length before the court, perennially hopeless,” for 24 years after Charles Ebbets’s death.25 When it was at last settled, in December 1949, Maie’s inheritance was reported to be $125,000 after debts and lawyers were paid.26 She didn’t live to enjoy it. She died of heart disease four months later.

By that time Cadore appeared to have regained his footing. Shortly before his wife’s death, New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Powers found him working as a salesman, fat and prosperous, “as wide across the beam as a 5th Ave. bus.”27 He told another writer, “Those cherries in those manhattans [are] pretty fattening.”28

The old pitcher took a last turn in the spotlight in 1955, when he, Ty Cobb, and Johnny Vander Meer appeared as mystery guests on the television game show I’ve Got a Secret. The celebrity panel recognized Vander Meer as the double no-hit pitcher, but Cobb, the all-time batting champion, and Cadore, the 26-inning iron man, stumped the panel and took home cartons of the sponsor’s cigarettes as prizes.29

With his health failing, Cadore moved back to Idaho and lived with a friend. He spent his final months in the veterans hospital in Spokane suffering from stomach cancer. When a nurse told him she didn’t care much about baseball, he replied, “I don’t care much for hospitals, either.”30 He died at 66 on March 16, 1958.

Joe Oeschger became a junior high physical education teacher and lived to be 94. Cadore and Oeschger, forever linked in baseball lore, met only once after 1920. They were guests at a San Francisco Seals old-timers day in 1957, two portly retired gentlemen who had earned a slice of immortality by setting a record that will never be broken.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Photo credit

Detroit Public Library

Additional Sources

The author wrote about the 26-inning game for SABR’s Games Project and the 2014 Hardball Times Baseball Annual. The unpublished play-by-play was provided by David W. Smith of Retrosheet. Additional information comes from game stories by the Associated Press, Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Brooklyn Eagle, Chicago Tribune, New York Times, New York Tribune, and The Sun and New York Herald.

Notes

1 The Brooklyn club was called Robins in some newspapers, Dodgers in others. The local Brooklyn Eagle called them the Superbas. Let’s stick with the familiar Dodgers.

2 Robert W. Creamer, Stengel: His Life and Times (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 123, 128.

3 Edward T. Murphy, “An Old Friend Recalls Cadore’s Wit, Inventions,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, March 22, 1958, in Cadore’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

4 Gonzaga University records show that he attended from 1905-1908 and received a commercial diploma to prepare him for office work.

5 Jenny Johnson, Stanford University collections management and processing archivist, email, January 24, 2018. Cadore’s name does not appear in the university’s student archives or its baseball yearbooks. City directories show him living in Spokane from 1908, when he left Gonzaga, to 1911, when he returned to Brooklyn.

6 “Only A Matter Of Location,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1917: 4.

7 “Cadore Looks Good To Your Uncle Robbie,” Baltimore Sun, August 2, 1917: 8.

8 Thomas S. Rice, “Indians Defeat Superbas 5-1,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 10, 1920: 1.

9 Michael E. Ruane, “The Harlem Hellfighters were captured in a famous photo,” Washington Post, November 11, 2017, online edition. The National Archives’ commemoration of the centennial of World War I featured an exhibit honoring the regiment.

10 Jim Leeke and Gary Mitchem, eds., Ballplayers in the Great War (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 96.

11 Gonzaga Bulletin 22:10 (1940).

12 Associated Press, “Zach Wheat recalls game of 26 innings,” Washington Post & Times Herald, June 7, 1962. C2.

13 United Press International, “Oeschger thinks pitching feat is no longer news,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, July 17, 1977: 33.

14 Murphy, “Cadore Recalls That 26-Inning Duel With Oeschger,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, April 30, 1955, in Cadore’s Hall of Fame file.

15 Jack McDonald, “50 Years Ago — Longest Game Ever in the Majors,” The Sporting News, May 16, 1970: 5.

16 “How It Seems to Pitch a 26-Inning Game,” Baseball Magazine, July 1920: 380.

17 Jerome Holtzman, “Endurance Doesn’t Stand Up the Way It Used To,” Chicago Tribune, April 30, 1989: 57.

18 Murphy, “Cadore Replays Longest Major Game — 26-Inning Brave-Dodger Tie in ’20,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1956: 11.

19 The National League ERA shot up after 1920 as the so-called Lively Ball Era took hold. The adjustments compensate for the increase in run-scoring.

20 “Their Bats May Win If Arms Should Fail,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1921: 6.

21 “Robbie Admits Making ‘Bum’ Guess Yesterday,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 10, 1920: 4.

22 “Leon Cadore, Superba Pitcher, To Wed Miss Helen Sweeney,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 8, 1920: 1.

23 “Leon J. Cadore, Ex-Dodger Star, Held in Fraud,” New York Herald, August 21, 1936, in HOF file.

24 “Mae E. Cadore, Daughter of Ebbets, In Need,” New York Herald, December 16, 1936, in HOF file.

25 Charles Dickens, Bleak House (e-book repr., Gutenberg Project, 1997), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1023/1023-h/1023-h.htm.

26 “Ebbets Estate Settled,” New York Times, December 15, 1949: 37.

27 Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouse,” New York Daily News, May 4, 1949, in HOF file.

28 Holtzman, “Endurance.”

29 Goodson-Todman Productions, I’ve Got a Secret, September 28, 1955, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cl0Df1CJtr0.

30 Fred Lieb, “Leon Cadore, Who Pitched 26-Inning Duel, Dies At 65,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1958: 32.

Full Name

Leon Joseph Cadore

Born

November 20, 1891 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

March 16, 1958 at Spokane, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.