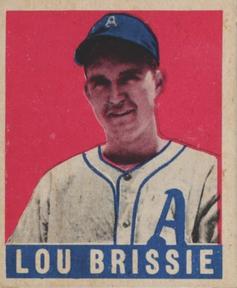

Lou Brissie

Lou Brissie still has the wristwatch he was wearing when a 170mm German artillery shell exploded near him, breaking the watch and both his feet and also shattering Lou’s left tibia and shinbone in 30 places. Shrapnel also pierced his right shoulder, both hands, and both thighs. And, one might assume, crushed Corporal Brissie’s hopes of ever playing professional baseball.

Lou Brissie still has the wristwatch he was wearing when a 170mm German artillery shell exploded near him, breaking the watch and both his feet and also shattering Lou’s left tibia and shinbone in 30 places. Shrapnel also pierced his right shoulder, both hands, and both thighs. And, one might assume, crushed Corporal Brissie’s hopes of ever playing professional baseball.

It was December 7, 1944 – the third anniversary of Pearl Harbor. Brissie was a squad leader in the 351st Infantry Regiment, 88th Infantry Division, United States Army, fighting against the German 1st Parachute Division in the Apennine Mountains near Florence, in the northern part of Italy.

Field surgeons wanted to amputate his leg, but Brissie didn’t want to hear that. “I’m a ballplayer! You’ve got to find another way,” he exclaimed. “I kept going from hospital to hospital,” Brissie recalls. “I don’t know if I convinced them but they kept sending me around trying to find a doctor who could do something for me.” The idea that he had any shot at playing baseball may have seemed far-fetched to doctors at the time, but the work they did helped make it possible.

Leland V. “Lou” Brissie Jr. was born on June 5, 1924, in Anderson, South Carolina, and was raised in Greenville and in Ware Shoals. His father had a motorcycle shop, and then joined Lucky Teeter and his Hell Drivers, an early daredevil thrill show. Lou Sr. ultimately found work running the maintenance department at the Riegel Textile Corporation in Ware Shoals.

Ware Shoals boasted the Riegel company baseball team during Lou’s ninth-grade year. Five of his uncles played in textile league teams in the Carolinas and at one point all five played for the Mauldin, South Carolina, team. “Our heroes were the guys that played in the textile leagues,” Lou recalled. None of them had ever seen — or heard a broadcast of — a major-league ballgame. Lou grew to become a 6’4½” lefthander, and by the time he was 14, he was pitching and playing first base for Riegel’s “B team” in Ware Shoals. It didn’t take long to graduate to the main team, and by the time he was 16, he was already fielding offers from major-league teams. His father greatly admired Philadelphia’s Connie Mack and even turned down a $25,000 bonus from the Dodgers, a very large sum in those days. The Dodgers pushed the idea that Lou could make the big leagues quickly, but “Mr. Mack had the reputation that if a fellow wanted to go to college, he’d work with him on that. Lou traveled to Philadelphia with Presbyterian College student Tom Clyde and coach Chick Galloway, a former major-league shortstop for the A’s and Detroit Tigers. They worked out for Mack, and Galloway brought home a contract for Lou’s parents to consider. Lou graduated from Ware Shoals High School on May 31, 1941, and signed with the Philadelphia Athletics right afterward. The deal was that Brissie would pitch for the Presbyterian College team for three years, then report to the Athletics. World War II interrupted those plans.

Lou pitched for the college in 1942, but wanted to enlist in the Army. Twice he tried to enlist but was too young, and his parents wouldn’t sign the necessary paperwork for him to enlist. “They wouldn’t talk to me about it,” Brissie said. “My dad’s view was, ‘You’ll be in there soon enough.’” Presbyterian had a strong military program and all students took ROTC. In late 1942, the students were told they could enlist, stay in school as long as they did the work, and then would be sent right into Officer Candidate School. Staying in college lacked appeal to many, and about 30 percent of the student body failed their course work almost immediately. “A lot of us had friends who had gone in the service, family who were in the service, and we just felt like that’s where we ought to be. A lot of us just coasted.” Lou enlisted in the Army in December 1942, but got in some time pitching for Presbyterian early in 1943 before he was asked to report in April.

He went through basic training and was stationed at Camp Croft in South Carolina, occasionally pitching for the base team. In the late spring of 1944, he struck out 19 batters in a game against the Greenville Army Air Base Jay Birds, but he’d topped even that in a game he pitched for the semipro Monaghan textile team while on a day leave, whiffing 22 Easley Mill batters – a game he lost 2-0 on a home run.

It was a few months into training that he learned of his uncle Robert Brissie’s death in North Africa. Robert was a little less than two years older than Lou, and was in the artillery. He was a private with the 354th Coast Artillery Battalion. He died on August 4, 1943, and is buried in Tunisia. Lou doesn’t know the details of Robert’s death, but remembers, “He was my first catcher. When we were kids growing up, I always would throw to him and we’d always talk about going to the big leagues together.”

In the latter half of 1944, Lou was shipped overseas. Serving with the 88th Infantry Division (the Blue Devils), he saw heavy combat in November 1944. During the 14 months the division was in Italy, it suffered very heavy casualties. When his G Company unit came under exceptionally heavy artillery fire on December 7, eight enlisted men from the company and three of their four officers were killed or wounded. His last conscious memory was of himself half in and half out of water and mud in a creek bed, one foot severely damaged and the other seeming to be missing.

Left for dead, Brissie was found unconscious several hours later, and doctors were ready to amputate. In three days of visiting hospitals, he was persuasive enough to convince doctors not to amputate his leg, and Dr. Wilbur Brubaker at the Army hospital in Naples worked on saving the limb. “Once he operated on me,” Brissie told Baseball Digest author Joe O’Loughlin, “I didn’t wonder if I could make it back to pitch, but how I could do it.”

Lou had kept in correspondence with Connie Mack, and after Mr. Mack heard of the injury, he wrote to Brissie on December 28, just three weeks after the wound. “He told me that my duty now was to try to get well, and whenever I felt I was ready to play, he would see I got the opportunity. That meant an awful lot to me. It was a tremendous motivator.” He would need it.

It took two years and 23 major operations on his leg, with 40 blood transfusions, but Corporal Brissie held to the hope of a return to baseball – albeit with a metal plate in his leg. He was apparently the first soldier in the Mediterranean Theater to be given penicillin in order to fight infection. “They had to reconstruct my leg with wire,” he said.

Strange as it may sound, he was probably fortunate that the German shell hit as close to him as it did. Shrapnel tends to disperse upwards and outwards and had it landed even a little further away, more would likely have cut into him above the knees and could well have killed him. Brissie was awarded a Bronze Star and two Purple Hearts.

After months in rehab hospitals, still hobbling around at home on crutches, Brissie told the Greenville News that his life’s ambition remained “to pitch big-league baseball and if I can’t make the grade I would at least like to get a job in the big-league ball park. And you know the man I want to work for — Mr. Connie Mack. His letters to me were wonderful. He wants me to come to Philadelphia as soon as I am able — just for a visit if nothing more.”

It was more than a year before Lou was able to get to the point that he could walk with a cane, but he began throwing a baseball while still on crutches. In July 1945, he traveled to Shibe Park in Philadelphia and worked out for Mack. It was an unusual tryout. “I propped up on one foot with a crutch and threw a few.” He stayed for several days, not yet discharged from the Army but on leave between operations. This was a determined man.

For Mack’s part, he gave Lou further encouragement, but there was real doubt in his mind. A year later, Mack confessed, “I’ll never forget how he looked last summer, he had just undergone an operation and was about to undergo another one. He was on crutches and I thought, ‘Poor boy. He’ll never be able to pitch again.’”

Lou kept working at it, and though he was derailed by a bone marrow infection in 1946, he convinced Mack of both his talent and his spirit. The Athletics owner declared, “If determination can do it, I know he’ll make good.”

His leg sufficiently stronger, Lou was signed again by the Athletics in December 1946. Wearing a hard protective brace, he was assigned to pitch for the Savannah Indians in 1947, and started off 13-0. By season’s end, he’d put up a 23-5 record. Savannah was in the very competitive Class A South Atlantic League, and Brissie did exceptionally well: He led the league in wins, strikeouts (278), and earned run average (1.91). Brissie struck out 107 batters more than his closest competitor, and the second-best at ERA (the only other pitcher under 3.00) came in with a 2.53 ERA. The Indians won the league championship.

It hadn’t been easy, though. Savannah catcher Joe Astroth said, “Though respect for Brissie was great, opponents gave him no quarter. Foes would probe any weakness, real or perceived. …Thinking that his injury limited his mobility getting off the mound to field grounders, hitters began laying down bunts against him to try to get on base.” Brissie turned out to be a pretty good fielder, catching several bunts in midair and turning them into double plays.

The day after Savannah won the Sally League championship, Brissie was called up to the big-league club and he made his major-league debut on September 28, 1947, pitching in the final game of the year against the New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium. It was Babe Ruth Day, and he had the opportunity to meet some great players from the past such as Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Cy Young, and more. It wasn’t his best performance. He gave up nine hits, walked five, and threw two wild pitches. He lost that game, 5-3, giving up five runs in seven innings, but enthused, “I thought I had gone to heaven. I lost the game, but it was still a great experience.”

Lou had launched a major league career that saw him win 14 games in 1948 and go 16-11 in 1949, despite struggling with pain every time he took to the mound.

On Opening Day 1948, Lou was given the honor of starting the second game against the Boston Red Sox during a Patriots Day doubleheader. The other starter for Philadelphia was Phil Marchildon, a former Royal Canadian Air Force gunner whose plane was shot down over Germany in August 1944 and was captured and interned as a POW at Stalag Luft III in Poland until liberation. Both Marchildon and Brissie pitched complete games and both won, Marchildon throwing 11 innings. Lou held the Red Sox to just four hits while striking out seven and walking just one. He even drove in the game-winning run with a two-RBI single in the fourth inning.

In the sixth inning, Ted Williams hit a hard shot up the middle, and it hit off the metal plate in Lou’s leg. Williams, Brissie said, could well have had a double, but held at first base, called time and came over to check on him at the mound. “When Ted leaned down, I said, ‘Damn it, Ted! Why don’t you pull the ball?’” Lou won the ballgame, 4-2, but Ted got Lou later. On May 31, he hit a two-run homer in Shibe Park. “Over the light tower in right field,” Lou remembers. “On his way around the bases, I said, ‘I didn’t mean pull it that much!’”

After the Opening Day game, Brissie was kept overnight in Faulkner Hospital for observation but was released in the morning and did not miss his next turn. Lou came in fourth in Rookie of the Year voting in 1948.

His was such a compelling story that Columbia Pictures expressed interest in making a film of his successful struggle to make the majors and pitch for the Athletics. The chief of staff of the 300th General Hospital in Naples had known Lou there, and then been reassigned to Walter Reed Hospital. He wrote Columbia and urged the idea on them, but Lou deflected the inquiry. They wrote me and I wrote back and told them I just wasn’t interested,” he explains. “I left a lot of guys in those hospitals and I just didn’t feel right about it.”

In 1949, Brissie was named to the American League All-Star team, and threw three innings, allowing two runs on Ralph Kiner’s sixth-inning home run. “I was like a kid in a candy shop, just sitting on the bench with all those guys like Williams, Lou Boudreau, and Joe DiMaggio,” he told Rich Westcott. “To pitch in the game was an added thrill.” Early in 1951, Brissie was traded to the Indians. Even though leaving a last-place team to pitch for perennial pennant contenders, he wasn’t at all pleased to be leaving Philadelphia. For the Indians, Brissie worked primarily as a reliever. After seven seasons in the majors — with Philadelphia and Cleveland – Brissie had a record of 44 wins against 48 losses, almost all of which came while with the Athletics during a span in which the team itself had a losing record. In 1953, the Indians sold his contract to their farm club at Indianapolis. Lou hadn’t been seeing eye to eye with Cleveland GM Hank Greenberg. Though there was some interest from the new Baltimore club, the Tigers, and the Yankees, Brissie closed his career after the 1953 season with a lifetime 4.07 ERA.

Three weeks after declining to report to Indianapolis, Brissie was named commissioner of the American Legion Junior Baseball Program, where he served for seven or eight years. It was a program in which over one million boys participated. He led a team of boys that played in eight Latin American countries in 1956 and the following year headed to Australia to try to better develop youth baseball there. The Legion released him in 1961 as part of a reorganization. The following spring, he took a position as a scout with the Dodgers and in 1964 began scouting for the Braves.

Brissie then went into private industry, doing some employee relations work and then becoming a company rep for United Merchants and Manufacturers, representing the firm in discussions and negotiations with regulatory agencies in Washington. After the company was bought out at the beginning of the 1980s, he served more than a dozen years with the South Carolina State Board of Technical Education working on job retraining plans as part of the state’s development program.

Lou lost his first wife in 1967 and married his current wife, Diana, in 1975. He has raised six children. Lou and Diana settled in North Augusta, South Carolina, and Lou continued to follow baseball in the area. For a number of years, he joined with Ted Williams and others in trying to get Greenville’s Shoeless Joe Jackson off baseball’s restricted list and into the Hall of Fame. Lou himself was elected to the South Atlantic League Hall of Fame in 1994.

He requires ongoing treatment at Veterans Administration hospitals and maintained regular visits every four to six weeks. The leg, having been broken so badly, started to bow a little, and there was ongoing concern about osteomyelitis. Only when asked about pain management did Lou admit that it’s been a constant in his life for more than 60 years. While pitching, he was pitching through pain and it’s never been banished; it’s with him on a daily basis. It’s just a matter of managing the pain. He downplays it, putting it in perspective: “You get up every day and it’s like having diabetes – which is something possibly worse, but it is a daily thing that you check and try to deal with, whatever comes up.”

Was Lou Brissie a hero? His characteristically modest response: “I don’t think I am. I knew some.”

Former New York Times sportswriter Ira Berkow has written a book on Lou’s life, with the working title The Corporal Was a Pitcher. Publication was scheduled for late in 2008.

Lou enthusiastically participated in the November 2007 conference at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, and on the final day proclaimed that he had just enjoyed “the most extraordinary three days of my life.”

“If someone tells you that you cannot climb the mountain, you set out and find a way to do it.” – Lou Brissie, in Baseball Digest

Sources

Interviews with Lou Brissie, November 2007 and January 2008

http://www.baseballinwartime.co.uk/player_biographies/brissie_lou.htm, with additional information from Gary Bedingfield

Michaux, Scott. “For the love of the game.” Augusta Chronicle, May 27, 2007

O’Loughlin, Joe. “Lou Brissie is an All-American.” Baseball Digest, June 2005

Sapakoff, Gene. “Lou Brissie, the real deal baseball hero.” Charleston Post and Courier, May 29, 2002

Westcott, Rich. “Lou Brissie” – for the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society

Full Name

Leland Victor Brissie

Born

June 5, 1924 at Anderson, SC (USA)

Died

November 25, 2013 at Augusta, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.