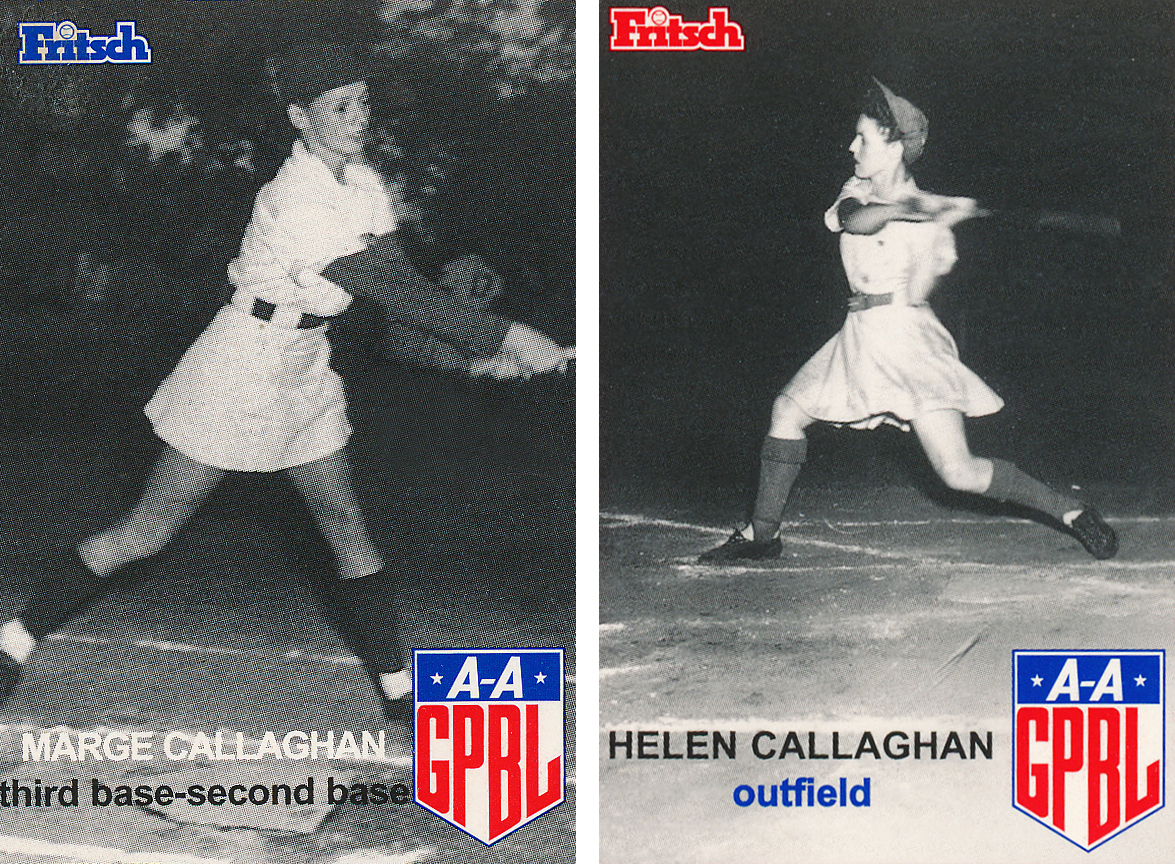

Marge and Helen Callaghan

Margaret “Marge” and Helen “Kelly” Callaghan, who were born and raised in Vancouver, British Columbia, made the wartime All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) and became regulars in 1944. The Vancouver girls, the first two sisters to play in the new women’s professional circuit, were not the fictional siblings featured in Penny Marshall’s famous 1992 movie, A League of Their Own, but both enjoyed good careers in the historic All-American league. The two were the fourth and fifth of the six children of Albert and Hazel Callaghan, and their names, with the eldest first, were Kay, Pearl, Lewis, Margaret, Helen, and Patrick. Their mother died early, Albert remarried, and he and his wife Anne had three children, Wayne, Elaine (Lani), and Dan.

All of the Callaghans were athletic, but Marge, born on December 23, 1921, and her sister Helen, almost 15 months younger, grew up playing sports like softball, soccer, lacrosse, and roller hockey in the streets with neighborhood kids, mostly boys. The Irish Catholic sisters went to the same elementary and junior high schools, and both attended King Edward High. Sharing the same interests, they played on the same teams, including basketball in the winter and track and field in the chilly spring. Marge left school in 1939 and Helen in 1940, and they were teammates on the fast-pitch Young Liberals, later renamed (due to a different sponsor) the Western Mutuals, a traveling team made up of local players from Vancouver’s city league. During World War II the pretty Callaghan girls worked for Boeing Aircraft and played for the Mutuals. The team competed in the World Championship Tournament in Detroit in 1943, and the sisters were scouted by the All-American League.

As a result, Helen was invited to the All-American League’s spring training at Peru-LaSalle, Illinois, in May 1944. The left-handed hitting Vancouver outfielder made the second-year circuit and was allocated to one of the loop’s two expansion teams, the Minneapolis Millerettes. In mid-summer Marge, after their father encouraged her to go, obtained special permission to leave her wartime position with Boeing, where she was a squad leader on the assembly line. She joined the Millerettes, who started the season playing games at Nicollet Park, home of the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers. However, the Millerettes didn’t draw well with a Double-A men’s team in town, and due to declining attendance, the girls’ nine became an “orphan” team in mid-season.

Marge, who was interviewed in 2011, remembered the difference between playing for the Mutuals in Canada compared to the Millerettes in the USA wasn’t great. During the war years the All-American League was playing a hybrid of baseball and softball, and the league used underhand pitching until the middle of the 1946 season. However, by the time Marge joined the Minneapolis team, the girls were playing all road games, living out of suitcases, and she needed a bigger glove. The sisters performed well as rookies, with Marge, a right-handed hitter who loved to bunt and hit-and-run, batting .182, while Helen hit .287, the second-best mark in the league after South Bend’s Betsy Jochum, who averaged .296.

Marge, a 5’3” right-handed thrower and batter, and Helen, who was two inches shorter and threw and batted left-handed, moved with the franchise in 1945 to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where the girls played together for three seasons (Helen didn’t play in 1947). Both were fast, but Helen was faster. “My reflexes were faster than hers,” recalled Marge, “and I got started faster, but she always beat me. She finished faster by about a step.”

Helen, who was interviewed by People Magazine in 1987, observed, “We were supposed to play like men and look like women.” She talked about the charm school offered by the league again in 1944. The players, many of whom grew up on farms, learned how to walk, sit, talk, wear their hair, and do their makeup properly. “That was an important to us as our playing,” Helen recalled. “And we weren’t supposed to drink or smoke in public since we were supposed to be ladies at all times.”

The AAGPBL, launched with four teams, developed from a hardball game using men’s baseball rules and underhand pitching in 1943 to a 10-team expanded league in 1948 that adopted overhand pitching, and the Callaghans lived through most of the changes. In 1943 the All-American League played games with a 12-inch circumference ball, the same as used in men and women’s fast-pitch softball. The ball was reduced in increments, starting with an 11 ½ ball in mid-1944, moving to an 11-inch ball in 1946, and through a 10 3/8 inch ball in 1948 to a 10-inch red-seamed livelier ball in mid-1949. As the league decreased the size of the ball, the distance from the pitcher’s mound to home plate and the length of the base paths were increased, also in increments, because the batters could hit the smaller ball harder. The ball and diamond size continued to evolve, since the league’s founders and managers always envisioned the girls playing baseball.

For example, the original pitching distance was 40 feet, compared to 35 feet in softball, and the first base paths were 65 feet, compared to softball’s 60 feet. However, All-American runners could lead off and steal from the beginning, making the game faster-paced. In mid-1944, when the ball was reduced to 11 1/2 inches, the base paths were lengthened from 65 to 68 feet. In 1945 the pitching distance was moved to 42 feet in mid-season to help the hitters, but no other dimensions were altered. In 1946, when the ball’s size was reduced to 11 inches, the base paths were reset at 70 feet. Sidearm pitching was introduced in mid-1946, and the sidearm style was fully adopted in 1947. In 1948, when the 10 3/8 inch ball was introduced, the mound was moved to 50 feet and the base paths to 72 feet. In mid-1949, when the livelier ball came into play, the pitching distance was 55 feet. In 1953 the pitching distance was moved to 56 feet and the bases paths to 75 feet. Finally, the league, facing demise in mid-1954, introduced a regulation baseball and made the pitching distance 60 feet and the base paths 85 feet. Thus, the AAGPBL evolved almost by the season, and the players kept adjusting. In that era many grew up as tomboys, playing baseball with boys on diamonds in the country, in small towns, and in cities.

During World War II and the immediate postwar years, the AAGPBL, a circuit that recruited, signed, and allocated the girls to teams, played mainly “small ball,” and the sisters thrived on that style of play. Marge and Helen enjoyed their golden summers, including living in homes of local families and sporting the Daisies’ pink uniforms with burgundy trim. A graceful fielder with quick hands, Marge played mostly third base, where her strong arm made her a fixture. She also played second base, but seldom shortstop. The Vancouver speedster batted second, following Helen, who was usually the Daisies’ leadoff hitter. Marge loved to bunt, and though her average always ranked below Helen’s, they worked well together. Marge bunted to advance her sister to the next base, or if Helen stole second and maybe third base, Marge sacrificed to score the run. Besides other Canadians, the sisters’ best friend with the Daisies was Dottie Collins, the circuit’s great underhand pitcher who was known as the “Strikeout Queen.”

The Callaghans, quiet but quick to smile, were first-rate athletes who understood the game and became exceptional baseball players, even though they came out of a softball background. Marge, bright, spirited, and likeable, with her long brown hair and dark brown eyes, always gave the game her best effort. Helen, whose flowing brown hair was a bit darker and whose hazel eyes flashed liked Marge’s, was the better hitter, but both loved every day they spent on the field.

The 1944 season proved difficult for the Millerettes, since the 16-player team lost its home base on July 22. Staffed largely with rookies such as the Callaghans, pitcher Dottie Wiltse, hurler Audrey Haine, and first baseman Vivian Kellogg, the Millerettes finished sixth (last) in both halves of the season (the league introduced a single-season format in 1945). For the season’s first half, when other teams made the six-hour train trip from Chicago to play at Nicollet Park, the Millerettes finished 23-36. In the second half as a road team, the Minneapolis entry posted a 22-36 record.

Dottie Wiltse, a curveballer who led the league with 205 strikeouts in 38 games, produced the team’s only winning record, 20-16. Annabelle “Lefty” Lee fashioned an 11-14 ledger, but Audrey Haine, the team’s number-three pitcher, finished with an 8-20 mark. In a loop dominated by fast pitchers, notably during the underhand years, Helen Callaghan, who had pop in her bat, topped the Millerettes’ hitters with her .287 mark. The fleet Vancouver star stole 112 bases, connected for five doubles, four triples, and three home runs (all inside-the-park shots), and contributed 17 RBIs from the leadoff spot. Margaret Wigiser, traded to the Rockford (Illinois) Peaches partway through the season, ranked second with her .212 average, Elizabeth “Lib” Mahon, traded to the Kenosha Comets after a few weeks, hit .211, and cleanup batter Viv Kellogg, never a speedster, batted .202 and paced her team with 46 RBIs.

Despite the hardships from traveling and living on the road, the Millerettes, in the words of Dottie (Wiltse) Collins (she married to Harvey Collins, a Fort Wayne native and Navy veteran, before the 1946 season), were being paid to play baseball, and they had a great time. Dottie, interviewed in 1997, recalled, “We were young, we were having a good time, and we had money in our pockets. I mean, what more could you ask for?”

The Callaghans echoed that sentiment. Further, the sisters liked having several Canadian teammates, making the league seem more like home. Marge said, “In 1945, after we moved to Fort Wayne, we had half a dozen Canadians on the team. Besides me and Helen, we had Penny O’Brian [later Cooke], and we had Yolande Teillet and Audrey Haine [later Daniels], and Arleene Johnson, but I don’t remember all the names.”

The Minneapolis franchise moved to Fort Wayne in 1945, and the expansion Milwaukee Chicks, who won the Shaughnessy Championship in 1944 over the Kenosha Comets, moved to Grand Rapids. In Fort Wayne the team held a contest, and a fan picked the new name, the Daisies. Fort Wayne, full of rookies who grew into professionals in 1944, ranked second in the six-team circuit with a 62-47 ledger, right behind the Rockford Peaches and their loop-best 67-43 mark. The Peaches won the Shaughnessy Championship (first place versus third place, second place versus fourth place, and winner versus winner) in the league’s last wartime postseason.

The Fort Wayne team, managed in 1945 and 1946 by former major leaguer Bill Wambsganss, or Wamby, was led by Canadians and Californians, many of whom were fun-loving girls. Helen Callaghan, who played all 111 games, led the circuit in 1945 with her .299 average. Enjoying a standout season, the speedy Helen contributed 17 doubles, four triples, and three homers, stole 92 bases, and produced 29 RBIs. She was followed in hitting on her team by Canadians such as catcher Yolande Teillet, who averaged .231 in 10 games. Third sacker Arleene Johnson batted .222 in 15 games. Outfielder Penny O’Brian hit .216 in 83 games. Viv Kellogg, who played the full 111 games, averaged .214 with 10 doubles, six triples, and one home run (she lost speed after injuring her knee), leading led her team in RBIs with 38. Marge Callaghan, a lifetime .196 batter, hit that exact mark in 1945. She played 99 games, mostly at third base, and her .912 fielding mark at the position was second only to Kenosha’s Ann Harnett at .922.

The top pitcher, also voted the league’s first Player of the Year, was Grand Rapids’ Connie Wisniewski, a tireless right-handed windmiller who fashioned a 32-11 record, and she was followed by Dottie Wiltse and her 29-10 mark. Dottie also hurled a pair of no-hitters against Rockford, achieving the feats on June 29 and July 15, 1945. The Daisies’ next best hurler was Annabelle Lee with a 13-16 record and a 1.63 ERA, and Lee no-hit Grand Rapids on July 7, 1945. Winnipeg’s Audrey Haine improved to 16-10 with a 2.46 ERA, and on August 26, 1944, she won a seven-inning no-hitter against Kenosha. On June 15, 1945, Haine participated in the league’s only double no-hit contest, a six-inning tilt against the Comets at Kenosha’s Lakefront Stadium.

Following the 1945 season, Helen married Bobby Candaele, also from Vancouver, but she returned to the league and played under her maiden name. The Callaghans enjoyed the first postwar season with Fort Wayne, but Helen’s hitting tailed off in 1946, and she didn’t play in 1947. The 5’1” 115-pound brunette, short of stature but long on spirit and determination, played all 112 games, but she averaged only .213. She still hit 10 doubles, three triples, and one home run, and she swiped 114 bases and contributed 26 RBIs. Marge, enjoying another stellar season at third base, hit .188 with two doubles, three triples, and a single home run, her second career home run.

The expanded eight-team league, featuring the Muskegon Lassies and Peoria Redwings in 1946, used a new 11-inch ball and allowed sidearm hurling at mid-season. Dottie Collins, a natural sidearmer, produced a 22-20 record, and strong-armed outfielder Faye Dancer, trying the mound after sidearming was allowed, posted a 10-9 ledger, but the Daisies, hitting just .184 as a team (seventh in the league), finished in fifth place with a 52-60 record. In 1947, when the league adopted sidearm hurling and held spring training in Havana, Cuba, the Daisies finished seventh with a 45-67 record. Marge averaged .201 with a pair of doubles, one triple, and one home run, a long blast at South Bend (she also homered in an exhibition game in Havana), stealing 57 bases and adding 23 RBIs. Helen, pregnant, stayed home. The Candaeles’ first son Richard was born before the 1948 campaign began with spring training at Opa-Locka, Florida.

Fort Wayne limped through another losing season in 1948, suffering a major blow when Dottie Collins, almost five months pregnant, left the team on August 1 in order to have her first child. Also, the Callaghan sisters played their final All-American season together. In 1948 the league expanded again, adding the Springfield (Illinois) Sallies and the Chicago Colleens, but both teams were staffed largely with rookies and players not among the protected top ten on the rosters of the eight established teams. Predictably, the Sallies and the Colleens finished last in the loop’s Western and Eastern Divisions, respectively. Fort Wayne ranked fourth (53-72), but the Daisies lacked the hitting and pitching to become a successful playoff team. Helen played 54 games in the first of the season, hitting .191, her lowest mark to date, but she suffered a ruptured tubal pregnancy, needed emergency surgery, and returned home in late July. Marge, who played all 112 games at second base, averaged .187 and helped anchor the Daisies’ infield.

Marge returned for the 1949 season and was swapped to South Bend, and Helen also returned, but she was traded to Kenosha. In mid-July the league adopted a livelier 10-inch ball, and most of the players saw their hitting improve. Helen Candaele, playing under her married name, finished her career with the Comets and made a comeback at the plate, averaging .251, the seventh-best mark in the league, and Marge, playing third base for most of the second half of the season in South Bend, hit .169. In the end, Helen left the game she loved to raise her family and help with her husband’s taxi business in Vancouver.

The Blue Sox traded Marge to the Peoria Redwings before the 1950 season. She played just 30 games as an infielder. She broke her ankle in a game on June 19, and her average for the season fell to .157. At one point, after manager Leo Murphy resigned in an economy move to help the financially strapped Redwings, the savvy Marge was considered for the post of interim manager, but the job went to Mary Reynolds. Marge returned to Peoria in 1951, but after an argument with the manager, she was traded to the Battle Creek Belles for the remainder of a season, hitting a combined .236 in 107 games.

“You wouldn’t believe how I got traded from Peoria to Battle Creek in the last part of the 1951 season,” Marge later explained. “In one game I was playing third base, and I picked up a grounder, and I turned around to throw to second, and the runner was there, but not the second baseman. So I turned and threw the ball to first base, and I got the runner going down to first. I was always taught, ‘If you can’t get two, get one.’ After the inning was over, the manager, Johnny Rawlings, came screaming out of the dugout, and he said, ‘What the hell do you think you’re doing?’

“I got my Irish temper up, and I screamed right back, ‘What the hell do you think I was doing?’ All the people in the stands stood up and yelled, ‘Atta girl, Marge – You tell him!’ And I guess that made him mad.

“I said to Johnny Rawlings, ‘I was always taught if I couldn’t get two outs, get one.’ He said, ‘You should have thrown to second base.’ I said, ‘It would have gone out between center field and right field, and the run would have scored.’ He said, ‘You should have thrown it anyway.’

“I couldn’t believe it! That just doesn’t make sense. I didn’t say any more, and I went over and sat down on the bench. Three weeks later, I got traded to Battle Creek. After Johnny Rawlings traded me, he got fired. He made everyone mad in Peoria, and he got fired. All those years and I never talked back to the coaches. I did what they told me, but I couldn’t see any sense to what the manager said on that play. He would have blasted me if I hadn’t thrown it to first. And I couldn’t figure out why he didn’t wait until I got into the dugout to say something to me.”

Marge added that the trade didn’t matter because she already had decided 1951 would be her final season. She met her future husband, Merv Maxwell, before leaving for the renamed American Girls Baseball League, and she was married after returning home to Vancouver. The Callaghan sisters were both finished as active professional players. They did team up again on local fast-pitch teams, until Helen and her family moved to California in 1956.

Both sisters had good memories from playing baseball in the AAGPBL. In her 1987 interview, recorded in part because her youngest son Casey Candaele was playing for the Montreal Expos, Helen explained that she grew up excelling at sports, notably softball. After she and Marge were scouted at the World Tournament in Detroit in 1943, she tried out with the second-year AAGPBL, made the league, signed a contract for $75 a week, and spent the season with the Millerettes. They played men’s rules but dressed in different uniforms: “We wore short, one-piece skirts, with shorts underneath, and knee socks, hats, and spikes.” The fans loved their uniforms: “This was the 1940s, and the team chaperones had skirts down to their ankles. But here we were in these little short skirts, thinking we were very feminine.”

Helen thrived in the All-American League. “I was a quiet and very intense gal,” she said. “I just went out every day and did what I could to earn a starting position.” She ranked second in the loop in hitting, earning her a raise to the highest possible salary, $125 a week for 1945.

“We were supposed to play like men and look like women,” Helen explained. The girls were supposed to behave like ladies at all times, and not to drink or smoke in public. “That didn’t always happen,” she reminisced, because sometimes the girls sneaked out after bed checks (the curfew was two hours after a road game ended). “Once during spring training we went to an Army camp, but the chaperones caught us there and gave us a slap on the wrist.” She indicated that boys followed the teams and wanted to date the girls. “And wherever we were, guys used to hang outside our hotel, hollering up to us, and we’d throw our bras down at them.” The players also played tricks on the managers, the chaperones, and rookies, maybe short-sheeting their beds.

“Fun times,” Helen remembered, “but we played tough, even when we were hurt.” The girls would have “strawberries” (bruises) on their legs from sliding in the skirted uniforms, but chaperones taped them up and they’d play again. The season lasted four months and ended with playoffs after Labor Day. “After a double-header,” Helen observed, “we’d shower, get dressed, travel all night on the bus, get to our hotel at 8 or 9 in the morning, shower, play two games of baseball in 110 degrees of heat, then do it all over again the next day.”

In 1987, when Helen’s middle son Kelly Candaele (she had five) and his friend Kim Wilson were producing a filmed documentary entitled A League of Their Own (Penny Marshall’s more famous movie took the same title in 1992), the experiences of Helen and Marge evidently motivated Kelly to envision a pair of sisters as central to the success of a fictional film about the league. Both sisters were modest, and as Helen later observed, “I seldom talked about it [the league] to my boys while they were growing up, but now I think the memories are great.”

Helen later contracted breast cancer. After a long battle against the disease, she died in Santa Barbara on December 8, 1992, at age 69.

Marge, however, pointed out that the film was not about the Callaghans, or any family. “The movie was written about the league,” Marge explained in 2011. “When anybody asks me, I always say the movie was about the league. My nephew, Kelly Candaele, took the idea of the movie to Penny Marshall in the first place. He produced a documentary, called A League of Their Own, about our league. Kelly took the story to Penny Marshall, but he did not have the rights to the title, so Penny Marshall and the producers called the movie A League of Their Own. But as I said, the story was not about anybody in particular – it was about the league.”

Marge had many favorite memories. Asked if the league made a big impact on her life, she agreed, saying, “Playing in the league was what I call a tremendous time in my life. There’s a lot of good things to remember. I really met some wonderful people, and I made a lot of friends. Penny O’Brian, who played the 1945 season, later moved out here from Edmonton, and we kept in touch over the years, until Penny passed away last year [2010]. We kept in touch and visited back and forth a lot. I kept in touch with Colleen (Smith) McCulloch. She played the one year for Grand Rapids [in 1949], and she was from Vancouver too.”

Asked if she and Helen were alike in personality, Marge laughed, recalling, “Helen was more forward than I was. She was more of a flamboyant type of ballplayer. We had a few ballplayers on our Daisies team that were like that. I was a little more reserved. I wasn’t going to go down and play in the league at first, but Dad wanted me to go because of Helen. He wanted me to keep an eye on her. That’s what he told me anyway!”

Helen always hit for a higher average and with more power than Marge, but the oldest sister still slugged three career home runs. “I did hit a few long balls,” Marge said. “I recall one game at South Bend where they recorded a home run I hit as the longest hit ball at that point in the league. The article in the paper said, ‘Marge Callaghan, who is one hundred and some odd pounds soaking wet, hit the longest ball of the season, and Betsy Jochum is still chasing it!’ I thought it was hilarious. I only hit two or three home runs all the time I played in the league, but I really hit that one!”

On July 25, 1947, reported the South Bend Tribune, Marge hit a long two-run home run in the ninth inning off right-hander Ruth Williams in Fort Wayne’s 7-0 victory over the Blue Sox at South Bend’s Playland Park. The ball carried over Betsy Jochum’s head in left field and bounced into Playland’s bleachers. Jim Costin, sports editor of the Tribune, compared Marge to a “feminine Ted Williams.” Costin called Callaghan’s home run “the longest ball ever hit in a girls’ pro game here, and probably as long as any other ever hit in any other park in the league, too.” Marge (Callaghan) Maxwell’s long ago blast left the kind of indelible memory that endures for ballplayers, women and men alike, as well as fans of the national pastime.

Marge Maxwell, who was divorced many years ago, retired and lived near her sister Lani in Delta, a city of 100,000 located 25 miles south of Vancouver, where the family lived during the league years. Marge valued her league memories as well as the friends she made playing baseball. She died at the age of 97 on January 11, 2019.

Photo credit

Photos courtesy of AAPGBL.com

Sources

Statistics for the “All American Girls Baseball League” were compiled from local newspapers by the Howe News Bureau, then located in Chicago. Copies of the annual figures are held in the AAGPBL Archives at the Center for History, South Bend, Indiana.

Files for individual players such as Marge (Callaghan) Maxwell and Helen (Callaghan) Candaele St. Aubin are held in AAGPBL Collection at the Library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame (BB HOF), Cooperstown, New York.

Interviews: Marge (Callaghan) Maxwell, October 3, 2011; Dottie (Wiltse) Collins, May 31, 1997; Audrey (Haine) Daniels, June 24, 2011. These were published as part of 42 AAGPBL interviews in my book, We Were the All-American Girls: Interviews with Players of the AAGPBL, 1943-1954 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013).

Website: A great deal of information about the AAGPBL, including rules, changes in ball size and diamond dimensions, players’ data, and more, can be found on the Players’ Association site: http://www.aagpbl.org/.

Articles

St. Aubin, Helen, as told to Todd Gold. “This Mother Could Hit: A Woman’s League Baseball Star Recalls Her Days with the Girls of Summer,” People Magazine, vol. 28, no. 7, August 17, 1987, pp. 77-79, copy in file of Helen (Callaghan) St. Aubin, BB HOF.

Candaele, Kelly. “Mom Was in a League of Her Own,” New York Times, June 7, 1992, copy in St. Aubin File, BB HOF.

Costin, Jim. “Daisies Hit Hard to Overcome Blue Sox, 7-0: Callaghan’s Homer Sets Park Record,” South Bend Tribune, July 26, 1947.

Helmer, Diana. “Mom Was a Major Leaguer,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 2, 1988, copy in St. Aubin File, BB HOF.

“Leo Murphy Quits as Redwing Pilot,” n.d. [1950], clipping in Marge (Callaghan) Maxwell File, BB HOF.

Books

The best book on the AAGPBL and its structure is Merrie Fidler’s The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006). Other interesting and useful books include:

Brown, Patricia L. A League of My Own: Memoir of a Pitcher for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), is the memoir of a former players, and Brown includes interviews with seven players and one chaperone.

Browne, Lois. Girls of Summer: The Real Story of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), covers the league, particularly during the 1940s.

Gregorich, Barbara. Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1993), has several chapters on the league years.

Heaphy, Leslie A., and Mel Anthony May, editors. Encyclopedia of Women and Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), contains useful bio information on the league’s players.

Johnson, Susan E. When Women Played Hardball (Seattle: Seal Press, 1994), details the players and the 1950 playoffs between Johnson’s hometown Rockford Peaches and the Fort Wayne Daisies.

Macy, Sue. A Whole New Ball Game: The Story of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1993), provides excellent highlights of the league from the origins through the AAGPBL Reunions.

Sargent, Jim, and Robert M. Gorman. The South Bend Blue Sox: A History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Team and Its Players (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), covers the history of the Blue Sox and the players made that team successful for 12 years.

Trombe, Carolyn. Dottie Wiltse Collins: Strikeout Queen of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005), is the first biography of an All-American.