Mark Baldwin

Mark Baldwin could burn the ball in there. He terrorized opposing batters with his nervous tics on the mound, which were usually followed by one of the swiftest fastballs of the 19th century, if not the swiftest. His catcher at Columbus of the American Association, Jack O’Connor, certainly thought he was the fastest. O’Connor said no one, including the great Cy Young, abused his hands more. Perhaps what concerned the batters more was Baldwin’s perpetual wildness. He was perennially among the league leaders in career statistics exemplifying pitcher wildness.

Mark Baldwin could burn the ball in there. He terrorized opposing batters with his nervous tics on the mound, which were usually followed by one of the swiftest fastballs of the 19th century, if not the swiftest. His catcher at Columbus of the American Association, Jack O’Connor, certainly thought he was the fastest. O’Connor said no one, including the great Cy Young, abused his hands more. Perhaps what concerned the batters more was Baldwin’s perpetual wildness. He was perennially among the league leaders in career statistics exemplifying pitcher wildness.

Off the mound, Baldwin’s career was fraught with controversy. He entered the major leagues amid an argument, as the Chicago White Stockings wanted to insert him into the rotation in the 1886 post-season championship against St. Louis of the American Association. But Baldwin hadn’t appeared with Chicago in 1886 and the umpires banned his use. He accompanied Albert G. Spalding and his White Stockings on the World Tour in 1888 but was released by the club when it returned for his raucous behavior and drinking. Baldwin jumped leagues twice, once to join the Players League in 1890 and again the following year, rejoining the National League rather than returning to the American Association. Both times he proved an effective recruiter for his new league. In the latter year, St. Louis owner Chris von der Ahe sought Baldwin’s arrest. The legal battle between the two volleyed back and forth in the courts for much of the decade. It was featured by multiple arrests, including a sensational kidnapping of von der Ahe from St. Louis to Pennsylvania.

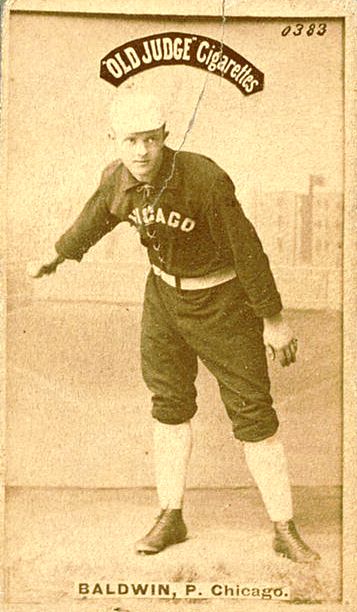

Baldwin’s nicknames, Fido and Baldy, were misleading. He was a big, good-looking, strongly-built athlete, dispelling the connotations Fido usually invokes. Baldy was a play on his name, not a reference to his hair, which was full and blond. After his baseball career fizzled, Baldwin entered medical school, obtained his license, and was a general practitioner and surgeon in his lifelong home of Pittsburgh for more than two decades.

Marcus Elmore Baldwin was born on October 29, 1863, in Pittsburgh, the older of two sons of Franklin E. and Margaret Baldwin. Franklin, a real estate agent and insurance salesman, was born in Virginia. Margaret was from Pennsylvania. Mark grew up in Pittsburgh and nearby Homestead. He began playing amateur ball in the area in 1880, at the age of 16. Baldwin, a right-hander, was a big guy for the era, 6 feet tall and weighing 190 pounds. He threw hard, as the Milwaukee Daily Journal noted in 1887: “Mark Baldwin is conceded to be the swiftest pitcher in the league.” The Galveston Daily News seconded the notion a couple of years later: “No speedier man lives than Baldwin, and his terrific speed has made him a terror to opposing batsmen. He is an untiring worker and a good pitcher.” In contrast, there was nothing remarkable about his curveball or changeup. And Baldwin had a glaring weakness: He was wild. He was second in career walks before the mound was moved back to 60 feet 6 inches in 1893; Mickey Welch topped him, but pitched 2,000 more innings. In more than ten percent of his major league appearances, Baldwin gave up at least ten runs.

After high school, Baldwin attended Pennsylvania State University. In 1885, he joined his first professional clubs, an independent Cumberland, Maryland, nine and McKeesport in the Western Pennsylvania League, helping the latter win the league championship. When he wasn’t on the mound, he played shortstop. The next year, 1886, was Baldwin’s breakout year. He pitched Duluth to the Northwestern League pennant, winning 27 of the club’s 83 games. On June 18, he fanned 18 St. Paul batters, 12 of them in a row. After the season, Baldwin signed with St. Paul of the same league in early October for a reported $150 a month; however, on October 20, he signed with the Chicago White Stockings of the National League. At the time, Chicago was playing the St. Louis Browns of the American Association in the 19th-century equivalent of the World Series, a tradition instituted in 1884. On October 22 Chicago pitchers Jim McCormick and Jocko Flynn were ailing. The other starter, John Clarkson, had pitched the previous day. Chicago manager Cap Anson inserted Baldwin into the lineup as the starting pitcher for Game Five. St. Louis owner von der Ahe strenuously objected, claiming that Chicago couldn’t use a player who wasn’t on their roster in 1886. (It didn’t help matters that White Stockings owner Spalding had already blocked von der Ahe from adding pitcher Toad Ramsey to his roster. Von der Ahe and Spalding argued, holding up the start of the game for 20 minutes. The umpires ultimately ruled that Baldwin was ineligible. Chicago shortstop Ned Williamson started the game. St. Louis won, 10-3, and took the championship the following day.

Baldwin joined Chicago in the spring of 1887. He nearly died in spring training; on March 17 at the club’s Hot Springs, Arkansas, hotel an employee walking outside Baldwin’s room smelled gas. He broke down the door and found Baldwin and his roommate, Tom Daly, unconscious. He couldn’t rouse them and immediately called for a doctor. Eventually, the two players were revived. One of them had accidentally blown out the flame in the gaslight. Refreshed, Baldwin later in spring training smashed what was said be the longest ball ever hit on a Hot Springs ballfield, a shot that knocked in two runs. During the season, Baldwin won 18 games and lost 17. He started 39 games for the club, alternating in the rotation with John Clarkson and George Van Haltren. A severely strained back slowed Baldwin toward the end of the season but he missed few starts. On September 29, he tossed a one-hitter over Pittsburgh. Player-manager Cap Anson hit a double, triple, and home run to seal the 4-0 victory.

Clarkson helped coach the young Baldwin on the tendencies of National League hitters. For example, Clarkson advised his young protégé to never pitch a low ball to Dan Brouthers, who would murder it. Also, Hardy Richardson had a hard time laying off shoulder-high pitches on the outside corner, perhaps even a little outside. In June, the Decatur Daily Review remarked, “Mark Baldwin, the young pitcher signed by Chicago, is doing excellent work in the box.” The Oshkosh Daily Northwestern said, “Mark Baldwin is the swiftest pitcher in the National League.” Baldwin achieved some of his success with his quirky, nervous delivery. The Daily Northwestern commented, “Mark Baldwin, of the Chicago club, goes through six different motions before he delivers the ball. He first passes his hand across his breast, then sizes up the ball, puts his right hand on the back of his head, looks at the ball again, closes his left eye and finally shoots the ball over the plate like lightning.” One of Baldwin’s odd habits was to constantly toss the ball from one hand to the other while on the mound.

Cap Anson called Baldwin “one of the jolliest and most companionable fellows in the business and at times a wonderful twirler, but uneven and easily rattled.” Anson credited Baldwin with badgering him into signing John Kinley Tener, a friend of Baldwin’s from Pittsburgh who had pitched briefly in the minor leagues and had played one game for Baltimore of the American Association. At the time, Tener was working as a bank clerk and pitching in amateur games around Pittsburgh. Anson checked out Tener the next time team was in Pittsburgh and signed him to a contract. Tener had middling success as a pitcher but became more famous as a congressman, governor of Pennsylvania and president of the National League.

Baldwin worked hard over the winter of 1887-88 to keep in shape. He was seen daily at a Pittsburgh gym. The doubting Oshkosh Daily Northwestern wrote in May that Baldwin “is somewhat deficient in headwork and is inclined to take things too easy,” and added, “If he will work and improve his opportunities his fortune is made.” But it was an unfortunate season for Baldwin. He fell ill and started only 30 games, not making an appearance between May 31 and July 13. He went home to Pittsburgh and lost over ten pounds during the period. After he returned, he injured his leg and didn’t make a start after September 7. He won 13 and lost 15 as Chicago placed second, nine games behind New York.

In October, Spalding invited Baldwin to join his overseas barnstorming trip, the World Tour of 1888-89. Baldwin had to convince his protective parents that he would survive the journey. Concerned, the elder Baldwins traveled with the group on the Western swing through the United States, and saw the group off at San Francisco. Baldwin was the club’s main pitcher during the tour; Tener also pitched. Baldwin partook in much of the trip’s alcohol-fed hijinks. At one point he was attacked by a monkey and bitten in the leg after parading it around the ship and feeding it pretzels and beer. The creature initially lunged for Baldwin’s neck. Baldwin’s funds ran out on the tour. He borrowed heavily from Spalding, upward of $800. (Spalding sued Baldwin in1897 to reclaim the money).

After the team arrived back in the United States, Baldwin, Tom Daly, Marty Sullivan, and Bob Pettit were released on April 24, Opening Day, by Spalding for their raucous behavior on the trip, though Spalding initially claimed that Baldwin was asking for too much money. Anson said he wanted to “have a team of gentlemen and would rather take eighth place with it than first with a gang of roughs.” He added, “I can’t say that Mark Baldwin has such habits but we can get better men.” For his part, Baldwin said no restrictions had been placed on the players about drinking during the tour, and he denied having taken part in some of the foolishness attributed to him. Perhaps another reason for Baldwin’s dismissal was the universal belief that he and Ed Crane, because of their traditional wildness, would be the two pitchers most affected by the new four-ball walk rule, a drop from five.

Baldwin was peeved by his release by the White Stockings. He had received other offers before leaving on the tour but had turned them down because he had been given assurances by Anson for the 1889 season. Baldwin said he was also mystified that no other National League team picked him up. So was the Pittsburgh Post, which asked why the local Alleghenys didn’t sign Baldwin, and surmised that some sort of collusion prevented a National League club from signing men discharged by another. On May 3, Baldwin he signed with the Columbus Colts of the American Association for a reported $3,500 to $4,000.

Pitching in a league-leading 63 games Columbus, including 59 starts, Baldwin won 27 games and lost 34 for the sixth-place team. He was a workhorse, pitching 513 2/3 innings and completing 54 games. He led the league in strikeouts, walks, losses, and innings pitched. His 274 walks were the second highest total before the mound was pushed back in 1893. Not known for his hitting, Baldwin banged a home run and two triples in one game. In another, his wildness showed as he walked ten batters and let loose six wild pitches (He had 83 for the season.) “I like pitching in the Association much better than in the League,” Baldwin said during the season. “The salaries and treatment given the players are greater and better, and there is more genuine fun and good fellowship among the players.” His catcher that year was longtime major leaguer Jack O’Connor. In 1897 O’Connor, then with Cleveland, recalled Baldwin fondly, calling him “the fastest pitcher I ever caught.” He called Baldwin “a magnificent specimen of physical manhood,” And said, “He could send them down the line like a rifle shot. When I joined the Cleveland club [in 1892] they tried to scare me with terrible tales of what ‘Cy’ Young would do to my hands. I was told that the big Ohio boy was the fastest twirler of them all, but he has never bothered me as much as Baldwin.”

After the season, Baldwin spent most of November hunting in Wisconsin with his brother. On November 21 he signed for 1890 with the Chicago Pirates of the upstart Players League, as did Silver King of the St. Louis Association team. They were among the early signers for the new league boosted by the players union, the Brotherhood. Chicago fans were happy to once again have Baldwin pitching in their city. On the 25th, Baldwin, acting as an emissary for union head John Montgomery Ward, took a train to St. Louis on a recruiting mission, and signed Joe Quinn and Yank Robinson. He also signed Jack O’Connor, but Jack jumped back to Columbus in January, claiming that Baldwin had got him drunk and took advantage of him. In December, Baldwin joined Charles Comiskey and a group that barnstormed into January out west as far as San Francisco.

Baldwin did a little dickering of his own in early 1890. He offered his services back to Columbus if it would match his Players League salary and pay the advance money he had already received. Columbus declined. Baldwin spent the season with Chicago and was again the workhorse of his league, leading in wins, games, complete games, innings pitched, strikeouts, and walks. Over two seasons, he had pitched more than 1,000 innings. His 33-24 record was by far the most impressive of his major-league career. Still, Chicago landed in fourth place, ten games out of first. On August, 11 Baldwin started and completed both ends of a doubleheader against Buffalo, winning the first game but losing the second. In October he again joined his brother for some hunting, this time in southern Colorado. He soon joined Comiskey in Denver for some postseason games. After the season, the financially-beset Players League folded. By initial agreement between the surviving National League and American Association, players would revert to their 1889 clubs. Thus, Baldwin was considered the property of Columbus of the American Association. In December Columbus business manager Gus Schmelz declared that there was no room for Baldwin in the rotation. But, though rumors abounded in early January that Columbus had sold Baldwin to Boston, Columbus denied the rumors and signed Baldwin on the 23rd for a reported $2,900. In February, Baldwin met with J. Palmer O’Neill, president of the hometown Pittsburgh Alleghenys of the National League, who had decided to start raiding American Association clubs. On March 1 Baldwin signed with Pittsburgh.

Two days later, he went to St. Louis on a recruiting mission and tried to land pitcher Silver King, who was the property of the Browns, and his old batterymate, Jack O’Connor of Columbus. He was successful in signing King for Pittsburgh. (The team had been known as the Alleghenys since its debut in 1882, but for stealing King, the club became known as the Pirates.) In St. Louis, owner Chris von der Ahe sought Baldwin’s arrest on conspiracy charges. Von der Ahe was still upset from the previous winter when Baldwin enticed his second baseman, Yank Robinson, to jump the club for the Players League and for likewise losing Charles Comiskey and Tip O’Neill, who jumped during a barnstorming trip that included Baldwin. Von der Ahe and his attorneys pushed hard, believing they were correct under Missouri statutes. On March 5 Baldwin was arrested at the Laclede Hotel in St. Louis on charges of conspiring with Pittsburgh president J. Palmer O’Neill and manager Ned Hanlon to sign King, who von der Ahe said was under contract with the Browns. The case against Baldwin was eventually dropped. In turn Baldwin filed a lawsuit in Philadelphia against von der Ahe for malicious prosecution and false imprisonment, seeking $10,000 in damages. After the case sat for several years, Baldwin withdrew it and refiled in Allegheny County so it could be adjudicated in his hometown of Pittsburgh. On March 3, 1894, von der Ahe walked into the Pirates’ ballpark and was taken completely unawares by a deputy sheriff. The Browns’ president was carted off to jail, where he posted a $1,000 bond, which was paid by Pirates’ president William Nimick.

At trial, Baldwin won a judgment for $2,500 against the Browns’ owner. On February 15, 1896, von der Ahe was granted a new trial on the grounds that an attempt was made to influence the jury. On January 20, 1897, Baldwin again was awarded a victory, this time for $2,525. Von der Ahe filed another appeal, but on January 3, 1898, the decision was affirmed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. A month later, von der Ahe still hadn’t paid the judgment. Nimick, now former president of the Pirates, decided that it was time to recover his bond. He obtained a warrant for von der Ahe’s arrest and hired detective Nicholas Bendel to execute it. A plan was hatched to get von der Ahe to come to Pittsburgh. It involved a fraudulent telegram asking for a meeting with von der Ahe; it was signed “Robert Smith.” Bendel and Nimick’s lawyers went to St. Louis and sent another telegram from Robert Smith seeking his companionship for lunch on February 8 at the St. Nicholas Hotel. When von der Ahe arrived for lunch, Bendel grabbed him, and eventually onto a train for Pittsburgh, where Von der Ahe was taken into court. He posted bail and slept at his attorney’s house. The next day he argued that he was illegally kidnapped but the arresting officer produced his legal warrant. Von der Ahe was released on $3,000 bail pending decision. His plea was ultimately denied. Von der Ahe was arrested again on February 12 after another suit was filed against him. He filed another appeal against Baldwin but it was dismissed. He paid the pitcher $3,000 in September 1898.

After the offseason, Baldwin’s 1891 season must have seemed anticlimactic. He posted a 21-28 record in 53 games. He started the season with some shoulder soreness, which sparked a running feud with sportswriters. Baldwin’s remaining time with the Pirates (he was released in May 1893) was contentious. At one point Baldwin was fined $50 for skipping a game. He demanded his release but manager Ned Hanlon denied his request and in fact inserted him into the lineup more often. On September 12, Baldwin pitched and won both games of a doubleheader against Brooklyn. Each was a complete game. At the time he was in the middle of an 11-game winning streak. It came to an abrupt end on September 18, and Baldwin finished the season with seven straight losses. In Chicago toward the end of the month, American Association agents approached him about returning to the Association. They promised to smooth over the troubles with von der Ahe and offered Baldwin a three-year contract for a reported $17,500. It was a desperate attempt by a failing league, though. The American Association merged with the National league before the next Opening Day. In November, Baldwin’s father bought into the Pirates, purchasing the stock of former president O’Neill. Mark spent November and December playing football around Homestead.

During spring training in 1892, Baldwin beaned teammate Billy Gumbert in Hot Springs. Gumbert was unconscious until the following day. The Xenia Daily Gazette reported, “Pitcher Baldwin is all broken up over the accident, as Gumbert was his personal friend.”

Baldwin appeared in 56 games for the Pirates in 1892, notching a 26-27 record. On July 6 he was involved in an ugly dispute at Carnegie Steel on behalf of the strikers against hired guards. A warrant was sworn out in early September, alleging that he incited a riot and passed out rifles to the strikers. He turned himself in and was released on a $2,000 bond. He was indicted later in the month but the charges were never brought to trial. Baldwin was still battling with the hometown press, fans, and even the club in 1892. He didn’t pitch between August 25 and September 7. During that time reports surfaced that the Pirates had released him. If so, he was soon brought back. A rift clearly existed, though. Over the winter, he refused the club’s contract offer, which called for a reduction in his salary and started selling insurance and real estate in Homestead as his father did. In February, Baldwin declared himself retired from baseball, and said he was exploring his options in business.

Nevertheless, Baldwin rejoined the club and started the second game of the season for Pittsburgh on April 28, 1893, a no-decision in a 5-4 loss. He was then released without another appearance on May 3. The Massillon Independent declared, “Baldwin’s abilities are not disputed. His only failing is an ugly temper.” Baldwin dickered with the Louisville club but ended up signing with the New York Giants on May 11, replacing Silver King in the rotation. Baldwin made his first appearance for the club nine days later, an impressive 2-1 victory over Washington. He posted a 16-20 record for the club, which finished fifth in the 12-team league, and was released at the end of the year, his major-league career at an end. He finished with a 154-165 record. With his dominant and erratic fastball, Baldwin’s strikeout and walk totals were strikingly similar: 1,349 to 1,307 respectively. Though he won more than 150 games, he had only two seasons over .500.

In 1894, Baldwin joined King Kelly’s Allentown Colts, popularly called Kelly’s Killers, in the Pennsylvania State League. The team also included Pete Browning, Mike Kilroy, Ted Larkin, and Sam Wise. Baldwin moved with Kelly to the Allentown Buffalos of the Eastern League, playing with the club through August. Baldwin then joined Pottsville in the Pennsylvania State League, a team managed by Phenomenal Smith. In 34 games in the Pennsylvania State League, he posted a 19-13 record. He finished the year playing four games with Yonkers in the Eastern League, winning twice. In October, Baldwin signed with Philadelphia of the National League but was released on April 29, 1895, without playing in a game with the club. Reading tried to sign him in May but Baldwin apparently asked too much money. Instead, he rejoined Pottsville in late May for seven games. On June 12, he signed with Rochester of the Eastern League but was cut in early August for allegedly drinking too much. The Milwaukee Journal wrote, “He is unable to curb his appetite for ‘conversation water,’ as the late King Kelly called whisky.” In 16 games with Rochester, Baldwin won 6 and lost 9. Baldwin also played two games, losing both, for Binghamton in the New York League.

Baldwin spent the winter of 1895-96 in Auburn, New York. In April his father put up the money to purchase the local semipro club. Baldwin organized the club with local ballplayers Tug Arundel and Jerry Dorsey and a businessman named John H. Farrell. The club was initially formed as a co-operative in which the players would share the profits as compensation. It soon reverted to the common practice of paying the men an outright salary. The team included longtime player Tim Shinnick, team captain, and pitchers Ed Crane and Frank Donnelly. The first game took place on May 6, a 15-1 victory over Hobart College. By August, Baldwin and Farrell were having trouble meeting payroll. After they had a run-in with local clergy for playing ball on Sundays, attendance started to lag, and the club went bankrupt just before the close of the season. In September, Baldwin, not quite 33 years old, enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia to study medicine.

In early 1897, Baldwin helped coach the University of Pennsylvania baseball team. During the summer, he pitched for the Carnegie Athletic Club of Pittsburgh. In the fall he returned to the University of Pennsylvania for his second year of medical school. In early 1898, Baldwin transferred to Bellevue Medical College in New York City to study dermatology. By midyear, he transferred to Roosevelt Hospital, also in New York City, to study surgery. In the fall he enrolled at Baltimore Medical College, where he played indoor baseball for the college in addition to his medical studies. He obtained his medical degree in April 1899. Toward the end of the year, Baldwin briefly coached football for the professional Duquesne Country and Athletic club, a team that included major leaguers Dave Fultz and Daff Gammons. Also in 1899, Baldwin played as a guard and team captain for Baltimore Medical College. Within a short time he established a practice in Homestead, outside Pittsburgh, working in connection with the Municipal Hospital. Maintaining his studies, Baldwin also assisted a coroner in New York City at one point and studied advanced surgical techniques at the Mayo Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, in 1905.

Baldwin ultimately obtained medical licenses in Pennsylvania and Ohio, focusing his practice in Pittsburgh and Columbus. He worked for years as a general practitioner and surgeon. At times he treated ballplayers, including Harry Lumley in 1907. In his spare time Baldwin painted, often landscapes, and was an ardent Republican and a Mason. He was never married. Baldwin died of cardio-renal disease at Passavant Hospital in Pittsburgh on November 10, 1929, at the age of 66. He was buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

Last updated: November 4, 2020 (ghw)

Sources

Minor league statistics provided by Ray Nemec

Altoona Mirror, Pennsylvania

Ancestry.com

Anson, Adrian Constantine. A Ball Player’s Career: Being the Personal Experiences and Reminisces of Adrian C. Anson. Era Publishing Company, 1900.

Atchison Champion, Kansas

Bismarck Daily Tribune, North Dakota

Boston Daily Advertiser

Boston Globe

Cash, Jon David. Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis. University of St. Louis Press, 2002.

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette

Charleroi Mail, Pennsylvania

Chicago Tribune

Christian Science Monitor

Cumberland Evening Times, Maryland

Daily Evening Bulletin, San Francisco

Daily Gazette, Xenia, Ohio

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago

Daily Picayune, New Orleans

Decatur Daily Review, Illinois

Denver Evening Post

Directory of Deceased Physicians

Fitchburg Sentinel, Massachusetts

Fort Wayne Sentinel, Indiana

Galveston Daily News

Hamilton Daily Democrat, Ohio

Hornellsville Weekly Tribune, New York

Indiana Democrat, Pennsylvania

The Independent, Massillon, Ohio

Janesville Gazette, Wisconsin

Logansport Journal, Indiana

Los Angeles Times

Miami Leader, Piqua, Ohio

Milwaukee Daily Journal

Milwaukee Sentinel

Naugatuck Daily News, Connecticut

Newark Daily Advocate

New York Times

North American, Philadelphia

Ohio Democrat, New Philadelphia

Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, Wisconsin

Oshkosh Record, Wisconsin

Penny Press, Minneapolis

Piqua Daily Leader, Ohio

Pittsburgh Post

Reno Evening Gazette

Retrosheet.org

Sporting Journal

Sporting Life

Syracuse Herald

Tiemann, Robert L. “Marcus Elmore Baldwin,” Baseball’s First Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996.

Trenton Evening Times

Washington Post

Yenowine’s Illustrated News

Full Name

Marcus Elmore Baldwin

Born

October 29, 1863 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

November 10, 1929 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.