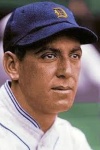

Merv Shea

Catcher Merv Shea played professional baseball from 1922 to 1944, starting in Sacramento at age 21 and finishing as the oldest man in the majors in 1944 with seven games for the Philadelphia Phillies.

Catcher Merv Shea played professional baseball from 1922 to 1944, starting in Sacramento at age 21 and finishing as the oldest man in the majors in 1944 with seven games for the Philadelphia Phillies.

He was a sturdy 5-foot-11 and 175 pounds, a right-hander like almost all catchers, and the son of Irish immigrants. Born in San Francisco on September 5, 1900, as Mervyn John Shea, his parents were Edward Shea, a laborer doing odd jobs at the time of the 1910 census, and Mary Sweeney Shea. He was the sixth of seven children in the family in 1910, all of whom were born in California. The eldest child was also named Edward, working as a lumber clerk. James worked as a loader in a canning works, and William was a messenger boy. The other children were 14 or younger – Elmer, Alice, Mervyn, and Evelyn. A daughter named Annie later joined the family. The family lived through the San Francisco earthquake; their home was demolished and they had to live outdoors for a night before they were taken in by a friend who brought them in his boat across the bay to Crockett, near the Contra Costa county seat, Martinez. They slept two nights on the floor of the California and Hawaiian (C&H) sugar refinery in Crockett, which still operates there. Edward Shea got a position as night watchman. Two years later, he was murdered and his body thrown in the river.1

Merv played third base and pitched in grammar school. When the regular catcher took ill, Merv started catching and made it his position. He attended schools in Crockett from grade 1 through 12.

Shea married early, in 1919. At the time of the 1920 census he was married to Clophine Shea and working as a laborer in a sugar refinery. In 1918, he’d worked as a weigher with the Sperry Flour Company in Vallejo and in 1919 in Stockton as a clerk for Ross Brothers.

Sacramento had a brand new ballpark in 1922 and a new manager, Charlie Pick. Elmer “Specs” Shea had pitched for Sacramento in 1921 with a 12-9 record. In 1922 he was joined by his brother, Mervyn “Mack” (or “Mike”) Shea, who was given a trial later in the season and appeared in 18 games. Merv committed seven errors, for an .879 fielding percentage, but he hit well, batting .362 in 47 at-bats. He only had one extra-base hit, a double. In 1923 he was “carried as a backstop, and as a relief catcher and hitter.”2 Mervyn appeared in 40 games, but this year batted only .208. The two brothers were a battery for several years.

In 1924 Merv more than doubled his work, getting into 81 games, and restored his batting eye, hitting .338. That year he hit his first home runs – four of them – and even pitched three innings in a game, on September 11 in Salt Lake City. In 1925, he bumped up to 141 games, doubled his homer total to eight, and batted .319.

He caught in 53 games in 1926. Each of his five years with Sacramento, his fielding percentage improved over the year before. Near the start of the 1925 season, Ed R. Hughes of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, “Mervyn Shea, a husky youth, who can throw like a shot and hit a baseball with tremendous power, is a big asset to the Sacramento club. He is a catcher and needs only steady work to make a fine player.”3

Major-league scouts were looking him over. Scout Ed Holly of the New York Yankees had made an offer for Jack Warner of the Vernon ball club in June 1925 and was said to be interested in Shea as well.4 A report on July 3 said that Shea had been “sold to the majors, or would be shortly.”5 Readers of the San Diego Union that same day were informed that Shea had split his finger. A July 5 report said that both the Yankees and Giants had been bidding for Shea, the Giants having offered $75,000 to Sacramento for him.6 This was later denied.7 On September 24, it was the Indians and the Reds who were said to be after him, but owner Lewis Moreing’s price was too high and no deal was done.

In 1926 a serious groin injury put him in the hospital for 41 days, from which he emerged “weak and drawn” near the end of June.8 He recovered and by August a full dozen clubs were interested. In February 1927, the Detroit Tigers landed him for a reported package worth $40,000.9 It was a conditional deal that gave Shea until May 15 to make the Tigers.

February was a busy month; before spring training began, Shea was granted a divorce on the grounds that Clophine had deserted him on October 5, 1925.10

He impressed at San Antonio from the start. One brief dispatch read, “Shea, the catcher from Sacramento looks every inch a ballplayer. It wouldn’t be astonished (sic) if he displaced one of the regular Tigers catchers.”11One of baseball’s more talented scouts, himself a general manager at one time, Billy Evans said it could be deceiving to only look at a catcher’s batting average. He quoted Tigers manager George Moriarty as ready to pay the sizable, but conditional, $40,000: “I like his style. He has one of the greatest arms I have ever seen….What Shea is able to do as a batter is giving me no concern. That is the least of my thoughts in sizing him up. There was never a more valuable catcher than Ray Schalk and his major league batting average is only about .250.”12

Shea was retained, third catcher on the staff behind Larry Woodall and Johnny Bassler, and he didn’t hit .250; he hit .176. He appeared in 34 games and drove in nine runs. His fielding percentage, with six errors, was .945. But he was a member of the fourth-place Tigers all year long.

He remained in a backup role the next two seasons as well. In 1928, behind Pinky Hargrave and Woodall, he played in 39 games and raised his average to .235 with another nine RBIs. In 1929 it looked like he would take the lead role; H.G. Salsinger of the Detroit News, for instance, simply declared, “Mervyn Shea is first-string catcher.”13 As it turned out, though, he was third-string again, behind Eddie Phillips and Hargrave, This time, Shea got into 50 games, put up a very good .290 batting average, and drove in 24 runs. His fielding percentage improved each year, too. Come October, the Tigers began to shake up the team, starting by selling veteran (and future Hall of Fame) outfielder Harry Heilmann to Cincinnati. Shea and Phillips both were named as others who would probably be let go.14

Just before Christmas 1929, Shea was in a deadly automobile accident. On the 22nd, an auto with three passengers “plunged over an embankment and overturned near the I Street bridge” in Sacramento. A hotel clerk was killed, a telephone operator was seriously injured, but Shea escaped injury.15 The following day, it was indicated that he had suffered some injuries, but not serious ones. The car had driven off the road in fog.16 Later stories said his wife was the third party in the car, and she spent nine weeks in hospital. The car had gone through a railing and fallen 30 feet.17 Without having gotten into a game, Shea was released to Milwaukee by the Tigers on April 19, four days into the 1930 season. He appeared in 81 games, this time second-string behind Russ Young. He hit .250. On October 31, he was traded from Milwaukee to Louisville for pitcher Americo Polli.

There was an incident in the middle of the 1931 season, when Shea was arrested for assault and battery on the complaint of Mrs. Nellie Seim, wife of a musician. Seim said she “was visiting a friend in Louisville and that during a party Saturday night Shea beat her when she criticized the Louisville team….He refused to discuss the affair.”18 The charges were dismissed five days later at the request of Seim’s counsel. Other than that, Shea had a decent season, appearing in 97 games and batting .266. And shortly after the season, he married again, in October to Ethel May Hutchinson, who had received her education in Sacramento. (Shea’s obituary gave her maiden name as Clayton, though those announcing the engagement said Hutchinson.)

Louisville had finished in first place in 1930, but (with no cause and effect implied) after Shea joined them in 1931, they finished in seventh place.

Shea played in 1932 for Louisville once more, batting .276 in 114 games. Louisville finished in last place. On January 7, 1933, he was positioned for another shot at the majors when the Boston Red Sox purchased his contract for an “unannounced amount of money” from Louisville; Sox owner Bob Quinn “said his new catcher was considered the best in the American Association.”19 Red Sox manager Marty McManus knew Shea from when they both had been with the Tigers. Quinn said that McManus believed Shea would be a “sure success in the big league.”20

For the first time, Shea was the starting catcher for a major-league team. He was behind the plate for opening day and caught 16 of the first 18 games on the schedule. But he was batting only .109 at the end of April, and had raised his average to .143 when he was dealt to the St. Louis Browns on May 9. The Sox got a Hall of Famer in exchange – catcher Rick Ferrell – and left-handed pitcher Lloyd Brown. A major ingredient in the deal was cash, understood to be $50,000; Tom Yawkey had bought the team and he had opened his checkbook and started acquiring players. The deal had been discussed before the season began, but took a while to be consummated. The Boston Globe was sanguine about Shea’s departure: “Mervyn Shea, who leaves the Red Sox, won’t be missed with Ferrell on the job.”21

Shea was the Browns’ first-string catcher, too, and appeared in 94 games for them, batting .262 and driving in 27. Just a week after being traded by Boston, on May 16, he kicked off an 11th-inning rally that did in the Red Sox. At one point in 1933, he handled 409 chances without an error. He finished the year with a .996 fielding percentage, leading the league among catchers. Before the year was out, he was with his third team, his contract traded to the Chicago White Sox on November 16 for catcher Frank Grube.22

In 1935, Shea worked in 46 games and hit .230 with 13 RBIs.

In 1936, when he wasn’t behind the plate (he appeared in only 14 games, hitting .125), Shea also worked as a coach. When manager Jimmy Dykes led the White Sox to a third-place finish, Shea got some of the credit. Muddy Ruel’s catching helped pitchers develop. But “it did not take [Dykes] long to learn that Mervyn Shea was even more valuable on the coaching lines than he was as a second string catcher.”23 He also did some scouting for the White Sox.

In 1937, Shea got into 25 games, batting .211 with five RBIs. On December 8, he was unconditionally released to the St. Paul Saints.

He trained in the spring of 1938 with the Saints. Because of an injury to their catcher, Babe Phelps, the Brooklyn Dodgers acquired Shea on May 2.

He played in 48 games, hitting .183 with 12 RBIs for Brooklyn, but near the end of the season, on September 22, he was released by the Dodgers. The batting average didn’t look good, but the Dodgers had a decent run at one point in July that earned him a headline in the New York World-Telegram: “Shea Given Credit for Dodger Streak.” Manager Burleigh Grimes said, “What’s happened to our pitching staff? Merv Shea is the answer. He deserves the credit. He’s cute as they come, a remarkable mechanical receiver, has an uncanny knowledge of batters, and above all, enjoys full confidence of the pitchers.”24

Above all, Shea was considered to be superb at studying pitchers and noticing how they were tipping their pitches. Herbert Goren wrote a column for the New York Sun that reported in detail how Shea had taken advantage of opponents in the American League like George Pipgras, Jimmie DeShong, Lefty Gomez, Mel Harder, and others. He claimed that about 50 percent of the time he could tell what pitch the man on the mound was starting to throw. Shea said, “A second-string catcher doesn’t have much time to get into the game, ordinarily, and when he has two or three hours on the bench for himself he ought to keep his eyes open and help any way he can. As a catcher, it was only natural to keep my eyes glued on those pitchers.”25

Six days after the Dodgers released him, Shea signed with the Detroit Tigers again as a coach for the 1939 season.26 He actually got into four games in August with two hitless at-bats.

Shea was quite a golfer, and in the annual baseball golf tournament he placed second in February 1940. In 1941, he won the tournament.27

He coached for the Tigers for the next three seasons, through 1942. The team made it to the World Series in 1940, losing in seven games to the Cincinnati Reds. Shea received a half-share. He managed the Tigers briefly in 1942 when manager Del Baker was indisposed. In November, both Baker and Shea were dismissed and Steve O’Neill brought in to manage. In December Shea was signed by the Portland club as catcher-manager. During the winter, he worked “tossing Coca-Cola crates” as a truck driver.28

Shea spent 1943 managing the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. The team finished last in 1942, but 79-76, in fourth place, in 1943. Shea appeared in 43 games, batting .221, but the Portland owner let it be known he was looking for a skipper who would play in more games, and so released him in October.29 In 1944 and 1945, he coached for the Phillies. In 1944, he appeared again as a player in seven games, mostly in August. He was 4-for-15 and batted in one run – with a home run, only his fifth in the majors.

Like most players of the era, he did other work, too. In 1945, he was a salesman for Crystal Cream and Butter Co. in Sacramento.

In 1948 and 1949, Shea coached for the Chicago Cubs, his last years in the big leagues. He appeared as himself in the 1949 MGM film, The Stratton Story.

Shea continued working as a West Coast scout for the Cubs from 1946 to1950, and worked as a coach for the Springfield Cubs (International League) in 1949 and 1950, then coached Sacramento in 1951 and half of 1952. SABR’s Scouts Committee credits him for signing two players, Paul Schramka and Bob Talbot. Due to illness, he had to leave the Springfield team on July 17, 1952.

In 1951 future Hall of Famer Joe Gordon had hit 43 home runs for Sacramento and he credited a lot of his success to Coach Shea, who was described as “one of the best ‘thieves’ of the diamond, in that he was able to tip off batters in advance as to the type of pitch which was to be thrown.”30 In his latter years, Shea conducted a number of clinics around Northern California.

On January 27, 1953, Shea died at Mercy Hospital, Sacramento, after what was described as a long illness (the one that forced him to leave the game the previous summer), a chronic hepatic abscess (of the liver), leaving his wife and six of his siblings.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Shea’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, Rod Nelson, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “New Pale Sox Backstop Has Eventful Life,” Dallas Morning News, January 8, 1934: 6.

2 “‘Shea and Shea,’ Calls Umpire In Announcing the Batteries,” State Times Advocate (Baton Rouge), July 26, 1923: 14.

3 Ed R. Hughes, “Senators Play the Seals Here This Week,” San Francisco Chronicle, April 21, 1925: 23.

4 “Cather Breaks Up Game with Double, Driving Kopp Home,” Seattle Daily Times, June 7, 1925: 25. See also “Huggins Will Rebuild Club,” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1925: B1.

5 “Three Stars to Go Up,” Seattle Daily Times, July 3, 1925: 17.

6 “New York Giants Want Merwin (sic) Shea,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 6, 1925: 21.

7 “Seen from the Press Box,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 11, 1925: 23.

8 “Seen from the Press Box,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 23, 1926: 29.

9 “Tigers Obtain Shea, Sacramento Catcher,” Boston Herald, February 3, 1927: 12. The story referred to him as “Haymaker” Shea, reflecting a fight in which he’d been involved during the 1926 season.

10 “Ball Player Gets Divorce,” Idaho Statesman (Boise), February 16, 1927: 8.

11 “Trailing the Big Leaguers,” Greensboro Record, March 2, 1927: 7.

12 Billy Evans, “Averages Are Often Off in Diamond Play,” Morning Star (Rockford, Illinois), March 3, 1927: 10.

13 H.G. Salsinger, “Tigers Have Improved Club In All Departments, Except Infield, Says Detroit Writer,” Washington Post, April 8, 1929:11.

14 “Heilmann’s Sale Presages Shifts in Detroit Team,” Hartford Courant, October 16, 1929: 13.

15 “1 Killed, 1 Injured in Plunging Auto,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 23, 1929: 1.

16 “Detroit Catcher Reported Improved,” San Diego Union, December 24, 1929: 15.

17 Typed manuscript in Shea’s Hall of Fame player file. Since he did not marry until 1931, reports that his wife was injured were incorrect.

18 “Catcher is Arrested,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, June 16, 1931: 9.

19 “Boston Owner Buys Backstop, Utility Player,” Advocate (Baton Rouge), January 8, 1933:16. The utility player was Bernie Friberg.

20 Burt Whitman, “Van Camp, Cash, Boston Angle of Transaction,” Boston Herald, January 8, 1933: 29.

21 “‘Sportsman,’” Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Globe, May 10, 1933: 22.

22 “Shea Traded to White Sox,” Boston Herald, November 17, 1933: 53.

23 Henry P. Edwards, “Jimmy Dykes Pilots Chicago Hose to Third Place in Race,” Dallas Morning News, January 31, 1937: Sect. IV, 6.

24 Dave Camerer, “Shea Given Credit for Dodger Streak,” New York World-Telegram, July 26, 1938.

25 Herbert Goren, “Shea Can Tell Coming Pitch,” New York Sun, August 16, 1938.

26 “Shea New Tiger Coach,” Lexington (Kentucky) Leader, September 28, 1938: 6.

27 New York Herald Tribune, February 10, 1941.

28 Steve George, “Shea Seeking Elixir,” unidentified December 17, 1942 newspaper clipping in Shea’s Hall of Fame player file.

29 “Portland Ousts Mervyn Shea As Manager,” Los Angeles Times, October 17, 1943: 19. When he had signed Shea, W. H. Klepper had said he expected Shea to catch in 80 games. “Portland Signs Merv Shea As Catcher-Pilot,” Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1942: B2.

30 Tom Kane, “Merv Shea, Solon Coach, ExMajor League Star, Dies,” Sacramento Bee, January 28, 1953: 8.

Full Name

Mervyn John Shea

Born

September 5, 1900 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

January 27, 1953 at Sacramento, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.