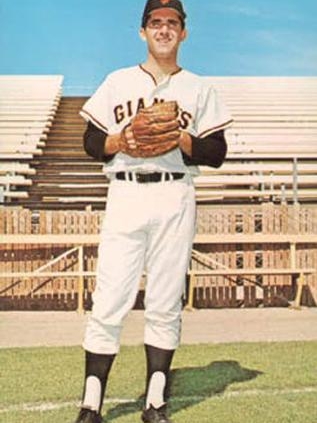

Mike McCormick

As a 33-year-old veteran outfielder, “call me Mike” McCormick was a major contributor to the Boston Braves’ run to the 1948 pennant. In 343 at-bats in 115 games, the right-handed-hitting McCormick batted .303, to help solidify the Braves outfield. A pinch hitter extraordinaire, Mike stroked six hits in 14 tries off the bench. He started all six games of the World Series, playing center or left field, and hit .261 in the Series (6 for 23) with two runs batted in. All told, McCormick played 2 1/2 seasons with the Braves and was always in the club’s outfield rotation.

As a 33-year-old veteran outfielder, “call me Mike” McCormick was a major contributor to the Boston Braves’ run to the 1948 pennant. In 343 at-bats in 115 games, the right-handed-hitting McCormick batted .303, to help solidify the Braves outfield. A pinch hitter extraordinaire, Mike stroked six hits in 14 tries off the bench. He started all six games of the World Series, playing center or left field, and hit .261 in the Series (6 for 23) with two runs batted in. All told, McCormick played 2 1/2 seasons with the Braves and was always in the club’s outfield rotation.

Myron Winthrop McCormick was born on May 6, 1917, in Angels Camp, California, the spot that triggered the California Gold Rush of 1849 after a mother lode of gold was discovered there. When he was 4 years old his family moved the family to Stockton, 20 miles away. Mike played third base at Stockton High and for the local American Legion team in the summer. He also ran track, winning the Northern California 100-yard dash title as a schoolboy and recording a 9.9 personal best.1 A Cleveland Indians bird dog and former pitcher named Carl Zamloch (he went 1-6 for the 1913 Detroit Tigers) spotted McCormick while he was in high school. Zamloch was an accomplished magician who could swallow fire, eat glass, and perform a host of magic tricks. As the story goes, he would display his magic to prospects on the West Coast, thus getting their attention before shifting talk to their baseball futures. It must have been effective, for Zamloch signed McCormick for the Indians at the tender age of 17.2

The Indians shipped Mike east to the Monessen Indians of the Class D Pennsylvania State Association for the 1934 season. In 49 games the youngster hit .235 while playing third base. In 1935 he was shifted to the Butler Indians in the same league and began to show major-league potential, batting .344 with 13 triples in 110 games to lead the league in both categories. His 46 errors and .888 fielding percentage, presaged an eventual move to the outfield but his bat earned him a promotion to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association for 1936. Still only 19 years old, McCormick hit .264 in 62 games in a utility role. He was assigned to the Buffalo Bisons of the International League for 1937 and there, playing first base and the outfield, batted .283 in 139 games and 498 official at-bats.

The following winter Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis entered the picture, ruling that the Indians, under their “gentleman’s agreement” with Buffalo, had exceeded their three option years on McCormick under the rules then in force. Landis declared Mike a free agent. He signed with the Washington Senators, who sent him to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association for the 1938 season.3 In 99 games in the outfield, McCormick made only one error. He hit only .250 but was affected by a badly sprained ankle suffered while sliding into second base. The injury sidelined McCormick for seven weeks and probably delayed his advancement to the big leagues by a year. He was back with Indianapolis in 1939 and showed his stuff, hitting .318 in 149 games and 547 at-bats.

McCormick’s hustle and quick baseball instincts made him a fan favorite in Indianapolis. Once he raced in to catch a Texas Leaguer in shallow center field and then continued on to tag second base for an unassisted double play. Another time, he tagged up at second and advanced to third on a long fly to the outfield. Mike noticed that the opposing outfielder was a little lackadaisical about returning the ball to the infield and so he kept running and scored.

The Cincinnati Reds had won the 1939 National League pennant but of their outfielders only Ival Goodman had really produced with the bat, hitting .323. As a result, the Reds purchased McCormick from Indianapolis, with whom the Reds had a working arrangement. Manager Bill McKechnie’s original plan was for McCormick to compete for the left-field job against the incumbent, Wally Berger as well as Lee Gamble, Arthur Luce, and Vince DiMaggio. Spring training injuries to Berger, center fielder Harry Craft, and right fielder Goodman further muddled the outfield picture.

Throughout the spring, however, McCormick performed well both at bat and with his speed in the outfield. The Reds barnstormed north with the Red Sox that spring and in the nine games they played after leaving Florida, Mike hit a lusty .382 with 13 hits, including four doubles, in 34 at-bats. That earned the 23-year-old rookie a spot in the Opening Day lineup against the Cubs in Crosley Field in Cincinnati. In his first big league at-bat, McCormick doubled against Bill Lee into the overflow crowd in left center. He later singled and in the eighth inning with the scored tied 1-1 fielded a hit slammed by Billy Herman as it caromed off a temporary fence near the left-field foul line, wheeled, and fired a strike to Billy Myers at second to nail a surprised Herman.

In his second game, a 2-1 pitching duel between Gene Thompson and Claude Passeau of the Cubs, McCormick drove in the Reds’ first run with an eighth-inning double and then scored the winning run on a Billy Myers single.

Mike soon slumped at the plate, however, and earned himself a spot on the Cincinnati bench. Harry Craft was also struggling at the plate and McKechnie soon began working McCormick into the lineup in center field. At midseason Mike was hitting only .245 but he quickly picked up the pace and became an outfield regular. He ripped off a 19-game hitting streak and during the last month of the season batted a robust .354 as the Reds pushed to their second straight pennant, winning by 12 games over the runner-up Dodgers. His late surge brought his average for his rookie campaign to an even .300 in 110 games and 417 official at-bats, tops on the club among outfielders.

The 1940 World Series matched the Reds against the Detroit Tigers, who had won the American League pennant by a single game over the Cleveland Indians. McCormick started and played every inning of the seven-game Series in center field, setting Series records, since broken, for putouts and chances accepted. The Reds won the world championship with Mike contributing nine hits, including three doubles, in 29 at-bats for a .310 Series average.

Just 23 years old, McCormick had reached the pinnacle of the baseball world as a rookie, becoming the regular center fielder on a World Series winner. The 1941 Reds had high hopes of a third consecutive pennant, with a team that returned mostly intact. They failed to hit out of the box, however, and McCormick was a chief culprit, starting off only 4-for-40 for an unglamorous .100 batting average and finding himself back on the bench. Just as in his rookie year, however, McCormick began to hit in the second half of the year and regained his regular position, alternating between center field and left field. The Reds never hit as a team, batting only .247 for the year and were never really in the race. They finished third with an 88-66 record, 12 games behind the Dodgers and 9 1/2 games behind the second-place Cardinals.

For his sophomore season, Mike batted a team high .287 in 110 games and 369 at-bats. Although the Reds as a team did not hit, their outfield was especially weak with the stick, with no one else batting over .250. Thus, McCormick was the Reds’ top outfielder heading into 1942. He was off to another typically slow start when he broke a bone in his ankle on Memorial Day, sliding into second base on a force play. The injury knocked him out of action for about 10 weeks and limited him for the balance of the season. For the year Mike got into only 40 games, batting .237 in 135 at-bats. Meanwhile the Reds, who hit only .231 as a team, slid to fourth place with a 76-76 won-loss record.

World War II was in full force in 1943 and McCormick received his induction papers just as the season began, even though he was married with a child on the way. He appeared in only four games for the ’43 Reds, with just two hits in 15 at-bats, before heading to McClellan Field in California to begin his military service. There Mike played for the McClellan Field Fliers, one of the strongest service teams in the country. The Fliers were able to field a team that included, in addition to McCormick, present or future big-leaguers Gerry Priddy, Ferris Fain, Bob Dillinger, Walt Judnich, Dario Lodigiani, Charles Silvera, and Rugger Ardizoia. Mike, Priddy, Fain, Silvera, and Yankee farmhand Carl De Rose also played on an undefeated basketball team that won the post championship.4 McCormick served a total of 27 months, much of in the Central Pacific Theater, and completely missed the 1944 and 1945 baseball seasons before his honorable discharge from the Army on October 22, 1945.

McCormick returned to the Reds in 1946, now 29 years old. Once again he got off to a slow start and in early June was hitting under .220. This time the Reds did not wait for his bat to come around but sold him on June 3 to the Boston Braves in a straight cash deal. The change of scenery was to Mike’s liking. In his second game with Boston, he homered, doubled, and singled against the Cardinals.5 With that kind of hitting, McCormick quickly found himself in the Braves’ outfield mix. In 164 at-bats for Boston, he batted .262 to raise his average for the year to a subpar .248. The Braves finished in fourth place with an 81-72 won-loss record, 15 1/2 games behind the first-place St. Louis Cardinals.

In 1947 the Braves improved to 86-68 and third place, only eight games behind the pennant-winning Brooklyn Dodgers. Plagued by another slow start, McCormick competed for playing time in left field and center field with Johnny Hopp, Bama Rowell, and Danny Litwhiler. Tommy Holmes, a perennial .300 hitter, pretty much owned right field. As the season wore on, Mike began hitting and by July he was starting four of every five games and batting over .300. Mike tailed off a little but still hit a solid .285 for the year in 92 games and 284 at-bats.

Trying to get more punch in the outfield, the Braves acquired disgruntled outfielder Jeff Heath from the St. Louis Browns after the 1947 season. They also traded outfielder Rowell and first baseman Ray Sanders to the Dodgers for second baseman Eddie Stanky. In a five-player deal with the Pirates, the Braves acquired the veteran outfielder Jim Russell and catcher Bill Salkeld. It was one of those years where every move paid dividends. Heath had a very productive year, batting .319 and providing much-needed power. Stanky was a real sparkplug and was hitting .320 when he broke his ankle on July 8 sliding into Brooklyn’s Bruce Edwards at third base. Veteran Sibby Sisti filled in ably for Stanky and rookie Alvin Dark broke in with a bang at shortstop, batting .322 to finish fourth in the batting race and third in the MVP voting while sweeping to the Rookie of the Year Award.

With Heath taking over left field, McCormick played center field, starting mostly against right-handers. He had a strong season, hitting .303 in 115 games and 343 at-bats and was in the lineup every day after Jim Russell was hospitalized with a heart ailment in July. The Braves, behind “Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain,” won the pennant by 6 1/2 games over the Cardinals. Heath broke his ankle in a gruesome play at the plate in Ebbets Field four days before the end of the season. Partly as a result of Heath’s injury, McCormick played every inning of the World Series against the Cleveland Indians, starting four games in center field and two games in left.

McCormick hit safely in every game but the first. In that game, a 1-0 Braves victory, he sacrificed Phil Masi to second base in the bottom of the eighth of a scoreless tie. That set up the controversial play in which Masi appeared to be picked off, although the umpire at second called him safe. Tommy Holmes eventually singled to left, scoring Masi with the only run of the game and sending Indians ace Bob Feller to defeat.

Mike went 2-for-4 in Game Two, a 4-1 Boston loss. He then had a pivotal at-bat in Game Six. The Braves were down three games to two and went to the bottom of the eighth inning losing 4-1. They rallied, scoring two runs to chase Bob Lemon, and with two outs had the tying run on third and the go-ahead run on second. McCormick came to the plate against Gene Bearden, who had shut out the Braves, 2-0, in Game Three and had been Cleveland’s best pitcher down the stretch. Mike grounded sharply back to Bearden, who snagged the one-hopper and threw to first to end the inning. If Bearden had been a righty instead of a southpaw, McCormick’s comebacker may have instead been a two-run single up the middle which likely would have evened the Series and forced a seventh game.

That Series at-bat would be the last one for McCormick in a Braves uniform. On December 15, 1948, Boston traded him to Brooklyn for former Dodgers legend Pete Reiser. McCormick was enthusiastic about moving to the Dodgers and planned on being an everyday outfielder for the Bums.6 It was not to be. Mike got off to his customary slow start and, bothered by nagging injuries, never got on track at the plate. For the 1949 season he hit only .209 in 55 games and 139 at-bats. The Dodgers won the National League pennant by a single game over the Cardinals before losing the World Series to the Yankees in five games. Mike appeared in only one game as a defensive replacement and did not have an at-bat in the Series.

Nor surprisingly, the Dodgers released McCormick shortly after the end of the Series. He was unemployed until the New York Giants signed him on January 4, 1950. Giants manager Leo Durocher admired McCormick’s work and was adding some veterans to a young club. Unfortunately, Mike again struggled at the plate in spring training and the early season and was released on May 19 after only four at-bats. He signed with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League and there regained his batting stroke, hitting .314 in 51 at-bats in 18 games. That prompted the Chicago White Sox to pick him up in June. He played the rest of the season for the White Sox, batting .232 in 55 games and 138 at-bats.

On December 11, 1950, the White Sox traded McCormick to the Washington Senators for Bud Stewart, in a swap of veteran outfielders. Senators manager Bucky Harris was happy to have Mike, commenting at the time the trade was made that “there are outfielders playing regularly in this league who are not as good as McCormick.”7 By the end of June 1951, the 34-year-old McCormick was batting .311 and had worked his way into the regular lineup. In one nine-game stretch, he exploded for 14 hits in 28 at-bats. Although he cooled off, for the year he hit .288 in 243 times up, playing in 81 games for the seventh-place Senators. McCormick was also tough off the bench, placing second in the American League with a .467 pinch hitting average (7-for-15).

Even with his productive 1951 season, the Senators opted to go with youngsters like Jackie Jensen and Jim Busby for 1952. On February 1, Washington unconditionally released McCormick, marking the end of his big-league career. Mike split the 1952 season between the Sacramento Solons and the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, batting .251 in 315 at-bats. In 1953 he was the player-manager of the Wenatchee Chiefs of the Class A Western International League. Mike batted .318 in 280 at-bats but the Chiefs still finished ninth in a 10-team league.

Mike worked as a coach for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League in 1954 before becoming a minor-league manager in the New York Giants farm system. In 1955 he managed in two cities in the Class A Eastern League. His club began as the Wilkes-Barre Barons and finished as the Johnston Johnnies after a July 1 move. The 38-year-old McCormick batted .355 in 62 at-bats for the Barons/Johnnies, mostly in pinch-hitting duty. The season marked the end of his playing days.

In 1956, McCormick found himself managing the Lake Charles Giants of the Class C Evangeline League, piloting the club to a fourth-place finish. The next year he split between managing the Springfield Giants of the Class A Eastern League, where he tutored a young outfielder from the Dominican Republic named Felipe Alou, and the Danville Leafs of the Class B Carolina League. The Giants placed him closer to home for 1958 with the Fresno Giants of the Class C California League. There Mike had his greatest managerial success, piloting Fresno to the regular-season pennant with an 85-55 won-loss record. His Giants also won the league playoffs, defeating the Stockton Ports two games to one in the first round and then taking four out of five against the Visalia Redlegs.

McCormick was back with Fresno in 1959 but the club was bereft of talent and finished far in the basement with a dreadful 44-96 record. He was assigned to the Pocatello Giants of the Class C Pioneer League for 1960 and again ended up with a last-place club, although future big leaguer Chico Salmon played for him and led the league in hits.

McCormick retired from baseball after 1960 and went to work for the Ventura Pipeline Construction Company in Ventura, where he had resided since 1946. In 1966 he was elected to the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame and was officially inducted on July 28 at Crosley Field. He frequently attended Los Angeles Dodgers games and was in Dodger Stadium on April 14, 1976, to watch the Dodgers’ home opener against the San Diego Padres. He suffered a massive heart attack at the game and died en route to the Queen of Angels Hospital. McCormick was only 58 years old. His survivors included his wife, Beverly, two sons, a daughter, and his father.8

McCormick’s major-league career spanned 10 seasons and six teams. He was an excellent outfielder and a heady baserunner. Although not a power hitter, he hit .275 for his career and played a major role in two pennant winners, the 1940 Cincinnati Reds and the 1948 Boston Braves. Plagued with slow starts at the plate through much of his career, he tended to come on very strong during the last half of the season when the pressure was on. In three World Series, two of which he started every game in the outfield, he batted a strong .288.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Notes

1. Cincinnati Reds Press Release, March 1940, Mike McCormick clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

2. The Sporting News, April 25, 1940, p. 3.

3. Ibid.

4. Unidentified clippings, dated September 23, 1943, and February 24, 1944, Mike McCormick clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

5. Unidentified and undated clipping, Mike McCormick clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

6. New York Post, March 1, 1949, p. 5.

7. The Sporting News, July 4, 1951, p. 11.

8. Unidentified clipping dated April 15, 1976, Mike McCormick clippings file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Sources

Allen, Lee, The Cincinnati Reds (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 2006), first published 1948 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1969).

Caruso, Gary, The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press, 1995).

Honig, Donald, The Cincinnati Reds — An Illustrated History (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992).

Johnson, Lloyd & Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, N.C., 1997, 2d ed.).

Kaese, Harold, The Boston Braves 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern Univ. Press, 2004), first published 1948 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Mulligan, Brian, The 1940 Cincinnati Reds (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2005).

The 1951 Baseball Register (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1951).

Werber, Bill & C. Paul Rogers III, Memories of a Ballplayer: Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s (Cleveland: SABR, 2001).

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Myron Winthrop McCormick

Born

May 6, 1917 at Angel's Camp, CA (USA)

Died

April 13, 1976 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.