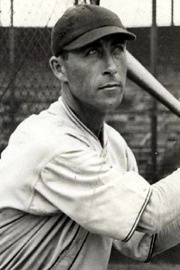

Norm McMillan

The shortest home run in major-league history? It was hit in 1929 by South Carolina’s Norm McMillan, who played every position except left field, catcher, and pitcher, but was remembered in his obituary for hitting that homer.

He was born in the small town of Latta in northeastern Dillon County. His father, Sidney Alexis McMillan, ran the general store in town – a town for which he’d surveyed and laid out the first street. Sidney also had a tobacco and cotton farm. Sidney and his wife, Sue Rogers, appear to have had two sons, Norman and Ernest, and a daughter, Aileen, who became head of the music department at Columbia Women’s College. Ernest became the superintendent of schools in Union, South Carolina.1

Norm was born on October 5, 1895, graduated from the Latta public schools, and attended Clemson A&M (now Clemson University) for three years, concentrating on veterinary science. With World War I in full swing, he was called to service during his junior year and wound up in the United States Navy, serving aboard the battleship Mississippi until he was discharged in December 1918.

McMillan was offered the opportunity to start a professional baseball career at age 23 with the Sally (South Atlantic) League’s Greenville Spinners. He was a shortstop, playing in 58 games in 1919 (he was ill much of the year) and a full 126 games in 1920. He hit .288 in his first season, and then .294 in 1920 with 14 home runs. He was a little porous on defense, making 69 errors in 1920 for a .907 fielding percentage. He did complete his studies and graduated after playing varsity baseball all three years. (He was graduated after three years when he was called to service in 1917.) McMillan was named All-Southern third baseman in his last year.

He was still of interest to the New York Yankees, who purchased his contract on August 3, 1920. They thought McMillan a promising prospect but wanted him to get more playing time in the minor leagues, though they did promote him all the way from Class C to Double-A on March 22, 1921, assigning him to play in the International League with the Rochester Colts. It didn’t hurt McMillan’s batting average, which climbed to .318 while his slugging percentage remained more or less stable. Although with just six home runs, he hit 23 triples. His defense had improved, playing the full season at third base. His success in 1921 boosted him to the big-league club.

Batting fourth and playing right field, McMillan made his majhor-league debut on April 12, 1922, at Washington, going 0-for-4. He was 2-for-4 with a triple and a run batted in the next day and 3-for-5 with four RBIs against Boston on the 18th. Playing under manager Miller Huggins, the 175-pound “Bub” McMillan stood an even 6 feet tall, but he was fast and several times was inserted as a pinch-runner for Babe Ruth, who was not.2 Though an infielder in the minor leagues, he served as a regular in New York’s right field and center field for the first several weeks of the season, while Ruth and Bob Meusel were serving five- week suspensions issued by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for barnstorming after the 1921 season. Meusel’s suspension was lifted on May 20, and he began to play that day in St. Louis. Even though McMillan was hitting .309 through April 30, he appeared in only two May games. Major-league veteran Whitey Witt was hitting over .400, and Witt got preference in the outfield, appearing in 140 games and batting .297. With Ruth and Meusel back and Witt hitting so well, McMillan became a reserve outfielder. He appeared in 33 games and hit .256 in 78 at-bats.

McMillan had two at-bats in Game Five of the 1922 World Series, but did not get a base hit. He did earn a share of the World Series money.

Red Sox owner Harry Frazee was hopeful of getting McMillan for his team, but the Yankees weren’t all that ready to let him go. They wanted Shano Collins or Joe Harris or Herb Pennock in exchange. Frazee drove a reasonably tough bargain and sent Pennock to New York but received McMillan, George Murray, Camp Skinner, and $50,000. The trade was executed on January 30, 1923, and worked out well for the Yankees; Pennock was later elected to the Hall of Fame.3 The Boston Globe thought it a deal done at the request of incoming Red Sox manager Frank Chance, who was in dire need of a third baseman. The Boston Post declared that the Red Sox team “was squeezed of the last drop of blood” when it let Pennock go; he was the only remaining member of the 1918 world-championship Red Sox team. The Yankees now had ten former Red Sox players on their 1923 roster, and the Red Sox had 14 former Yankees. In 1923 New York won its first World Series; Boston finished in last place.

McMillan played third base, second, and short in 1923 and appeared in 131 games, but batted only .253 and drove in 42 runs. At least a couple of times his errors in the field cost the team games and put him in the headlines. He committed 35 errors in 1923.

McMillan appeared set to become Boston’s first-string third baseman for 1924 but was suddenly traded to the St. Louis Browns on April 14 for Homer Ezzell. New Red Sox manager Lee Fohl was hoping for an upgrade in batting. McMillan hit .279 for St. Louis, but played in only 76 games. Ezzell hit a comparable .271 in 90 games.

In January 1925 St. Louis was evidently very high on catcher Leo Dixon, and sent Pat Collins, Raymond Kolp, and McMillan to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association to get him. As if that weren’t enough, the Browns also sent some cash and allowed the Saints the use of two other players. McMillan played three seasons for Double-A St. Paul – 1925, 1926, and 1927. He played second base all three years and played some of his best defense, as measured by fielding percentage. He hit .287 in 1925, and then improved to .289 in 1926 and .305 with 11 homers in 1927, at age 31.

By executing 213 double plays in 1927, the Saints set an American Association record. The Sporting News ran a photograph of McMillan, Oscar Roettger, and Leo Durocher, and wrote, “McMillan, in particular, [was] a star in instigating double plays.”4 McMillan also led the league in stolen bases, with 42. An assessment in print: “McMillan gave the impression here [in St. Paul] earlier that he was a good front runner, but this opinion was shattered last season when he stayed in there for practically every game and hustled from first to last. Only by hustling could he have been such an important cog in that infield, which hung up such an awe-inspiring mark.”5

On October 4, 1927, McMillan was selected by the Chicago Cubs in the annual draft. He made the team out of spring training on Catalina Island and appeared in 39 games, splitting his time almost equally between second base and third base (though showing much better fielding at second). Manager Joe McCarthy used him as a utility infielder, not for his bat. McMillan hit only .220 in 1928, but third baseman Clyde Beck switched roles with McMillan in 1929, with Beck becoming the backup and Bub taking over as first-string third baseman. An unattributed typescript found in McMillan’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame says that Cubs manager Joe McCarthy’s “gesture was one of either sublime faith or dark despair when he finally told McMillan one day last June to ‘go out there and play that third base for the rest of the season.’” McMillan played in 124 games and hit .271, while Beck hit .211 in 54 games. Although he led the National League in errors at third base that year, it was McMillan who played for the Cubs in the 1929 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics. The Cubs lost in five games, and McMillan managed two singles in 20 at-bats. He struck out six times and neither scored nor drove in a run.

On August 26, 1929, however, McMillan hit the ball thought to have been the shortest home run ever hit in big-league history. It went about 100 feet. The Cubs were home at Wrigley Field, hosting the Cincinnati Reds. Chicago had been on the short end of a 5-2 score heading into the bottom of the eighth. By the time McMillan came up to bat, the score was tied and the bases were loaded with two outs. “I hit a ball that bounded over third base,” he told The Sporting News years later. It bounced foul and into the Cubs’ bullpen and slipped up inside the discarded jacket of relief pitcher Ken Penner, which had been lying on the ground “about ten feet behind the base. As it turned out, the ball went up the sleeve of the jacket and while the Reds’ left fielder, third baseman, and shortstop were all looking for the ball, we all raced home.”6 Penner appeared in only nine major-league games, four in 1916 and five in 1929, but his jacket helped win this game for the Cubs, 9-5, on McMillan’s 100-foot grand slam. The Associated Press may not have seen it, either, dubbing it a “freak home run which took a bounce into the stands.”7 McMillan may have exaggerated the distance; the Chicago Tribune’s veteran sportswriter Irving Vaughn said that Penner’s jacket was about 60 feet past third base – which would still make it a 150-foot home run. Vaughn explained that the Reds fielders never did find the ball, even though one of them picked up and shook Penner’s jacket while in the hunt, thus excusing a perhaps-hastened AP dispatch. It was only after the game when Penner put on his jacket that he found the ball lodged inside his sleeve.8

On December 5 Cubs president Bill Veeck traded McMillan to Double-A Kansas City for a right-handed pitcher, Lynn Nelson (who was something of a phenom), a player to be named later, and a “bundle of cash.”9

McMillan hit .326 playing second base for the Kansas City Blues in 1930. When shifted to third in 1931, he didn’t fare well in the field (an .871 percentage) – though he excelled at the plate, batting .354. After 30 games he was traded to Chattanooga and appeared in 27 games there, hitting .271. In January 1932 Reading obtained McMillan from Chattanooga and he played in his last 38 games of Organized Baseball, hitting .315 (often pinch-hitting) and back at his more comfortable position at second base for the 20 games he played on defense.

After baseball McMillan returned home to his beloved bird dogs in South Carolina and married Sara Lucretia Varn in April 1932. He prospered as a pharmacist during the Depression, noted in 1935 as owning a chain of drugstores in South Carolina.10 He also became a cotton and tobacco farmer. He maintained an interest in baseball and coached American Legion ball for many years, one of his teams winning the South Carolina state championship. He said he’d always taught his teams to play for one run at a time, the way he had when he’d been a ballplayer.11

Norman McMillan died of emphysema in Marion, South Carolina, on September 28, 1969.

This biography appears in “Winning on the North Side: The 1929 Chicago Cubs” (SABR, 2015), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed McMillan’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1929.

2 This work earned him this headline for his obituary in the September 30, 1969, Boston Record American: “McMillan, Pinch Runner For Babe Ruth, Dies, 73.”

3 New York Times, December 22, 1922, and Boston Globe, January 31, 1923.

4 The Sporting News, December 1, 1927.

5 The Sporting News, December 8, 1927.

6 The Sporting News, October 11, 1969.

7 See, for instance, the New York Times of August 27, 1929.

8 Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1931.

9 Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1929.

10 Hartford Courant, April 28, 1935.

11 The Sporting News, October 11, 1969.

Full Name

Norman Alexis McMillan

Born

October 5, 1895 at Latta, SC (USA)

Died

September 28, 1969 at Marion, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.