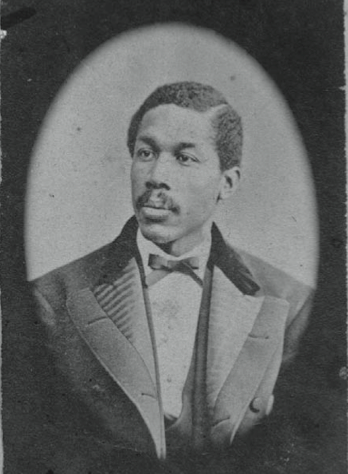

Octavius Catto

While the North’s Civil War victory and the 13th Amendment ended slavery in 1865, ensuring political and civil rights for blacks remained an unsettled question. During the war, a new generation of black leaders emerged to succeed old abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Among them was Octavius Catto, a Renaissance man who pioneered black education, integrated Philadelphia’s streetcars and the U.S. military, led the city’s civic and intellectual life, and promoted black voting rights — for which he died as a martyr. He was also the founder, captain, and star shortstop of the black Pythian Base Ball Club, which became a major vehicle for his work as a civil rights activist.

While the North’s Civil War victory and the 13th Amendment ended slavery in 1865, ensuring political and civil rights for blacks remained an unsettled question. During the war, a new generation of black leaders emerged to succeed old abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Among them was Octavius Catto, a Renaissance man who pioneered black education, integrated Philadelphia’s streetcars and the U.S. military, led the city’s civic and intellectual life, and promoted black voting rights — for which he died as a martyr. He was also the founder, captain, and star shortstop of the black Pythian Base Ball Club, which became a major vehicle for his work as a civil rights activist.

Catto was born free on February 22, 1839, in Charleston, South Carolina to a free black mother, Sarah Cain, and to William Catto, who was born a slave but earned his freedom and became a Presbyterian minister. William moved his family to Baltimore, intending to take passage to Liberia as a missionary in 1848. But when the Presbytery discovered a letter he wrote that it believed threatened to “excite discontent and insurrection among the slaves,” the Catto family fled an arrest warrant north of the Mason-Dixon line to Philadelphia. There, William became an active abolitionist and rights advocate through the 1850s, profoundly influencing his son, Octavius.1

While Philadelphia became a primary destination for freed slaves, it was not the paradise they envisioned. In an oft-repeated observation, well into the next century, Frederick Douglass claimed no northern city was more prejudiced against blacks than Philadelphia, the “City of Brotherly Love,” and yet it “held the destiny of our people.”2 As the seat of the North’s largest black population, the city had a particular impact on the future of black civil rights. Philadelphia was also a hotbed of amateur baseball.

In 1854, Octavius Catto attended the Institute for Colored Youth (ICY) (later the nation’s first historically black college, Cheyney University), Philadelphia’s only black high school. The Institute was a focal point for educational activism in pursuit of black civil rights. Catto was a star student and valedictorian at the ICY, where he also played cricket, town ball, and baseball. After pursuing further studies of languages and the classics in Washington, D.C., Catto returned to Philadelphia in 1859, when he was hired by the ICY to teach English, mathematics, Greek, and Latin.

In 1864, Catto delivered the school’s commencement address, challenging the insensitivity of white teachers (toward black pupils) and advocating political activism, not merely the education of black youth. He rallied support for a Northern victory in the Civil War, claiming it would liberate not only blacks but also America’s promising future: “It is for the good of the Nation that every element of its population be wisely instructed in the advantages of a Republican Government.”3 Fearing his militancy, however, the ICY’s Quaker trustees derailed Catto’s bid to become Head of the school.

Although his reputation for scholarship and teaching was already so great that he was offered principalships of black schools in both New York and Washington, D.C., Catto remained at the Institute. With Philadelphia as his base, Catto first expanded his reach into the city’s intellectual communities. And he was soon interacting with leading intellectuals from around the nation and the world, speaking repeatedly at events and gatherings to expose the barriers of racism.

Besides education, Catto’s next target was the U.S. military. Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation invited blacks to enlist in the war effort. As the ICY alumni association president, Catto rallied graduates and other Philadelphia blacks to join up: “Men of color to arms! Now or never!” With Confederate soldiers on the Maryland-Pennsylvania border, foreshadowing the Battle of Gettysburg, nearby Philadelphia felt particularly threatened and the Pennsylvania governor launched an urgent recruitment. But when Catto led dozens of blacks to Harrisburg to enlist, they were turned away — despite the emergency — and told that blacks could serve only if they made a three-year commitment. While Secretary of War Edward Stanton reversed this ruling, Catto’s recruits had already returned to Philadelphia.

Besides their patriotism, Douglass and Catto believed that enlistments would help ensure post-war, black civil rights. Catto was tireless in rallying black recruitment, leading the effort to raise eleven regiments of U.S. Colored Troops for the Union Army. He helped establish a Free Military School, joined the Pennsylvania National Guard, supported black troops at Camp William Penn, and was quickly elevated to major and inspector for the 5th Brigade.

After the war ended, Catto was selected to address a large crowd at Independence Hall, to send off the 24th U.S. Colored Troop, which had been assigned to help occupy post-war Richmond, Virginia. Speaking to many of his former students and recruits, Catto praised the two hundred thousand blacks who, despite prejudices, had nobly fought for the Union, “trusting to a redeemed country for the full recognition of their manhood.” Unfurling a flag with the words “Let Soldiers in War be Citizens in Peace,” he hoped that during Reconstruction, “the votes of the blacks could not be lightly dispensed with.”4 The reality, however, was not as bright.

After the war ended, Catto was selected to address a large crowd at Independence Hall, to send off the 24th U.S. Colored Troop, which had been assigned to help occupy post-war Richmond, Virginia. Speaking to many of his former students and recruits, Catto praised the two hundred thousand blacks who, despite prejudices, had nobly fought for the Union, “trusting to a redeemed country for the full recognition of their manhood.” Unfurling a flag with the words “Let Soldiers in War be Citizens in Peace,” he hoped that during Reconstruction, “the votes of the blacks could not be lightly dispensed with.”4 The reality, however, was not as bright.

Catto broadened his civil rights activism. In 1864, he met in Syracuse, New York with hundreds of blacks from the North and South to form the National Equal Rights League, the first U.S. group devoted to promoting black equality. Catto helped form and was then elected secretary of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League.5 In 1865, he served as the vice president of the State Convention of Colored People in Harrisburg. And he worked zealously alongside Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists to pass the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. He traveled to Washington, D.C. to help develop school curricula there, and to advocate for the 14th Amendment, which would require due process and equal protection from the states.6

While maintaining his ICY teaching position, Catto crusaded for black rights by participating, and sometimes integrating, Philadelphia civic, literary, patriotic, and political groups, such as the Philadelphia Library Company, the 4th Ward Black Political Club, and the Union League Association, which he addressed in a January 1865 speech. An eloquent, powerful, and charismatic speaker, Catto claimed “it is the duty of every man, to the extent of his interest and means to provide for the immediate improvement of the four or five millions of ignorant and previously dependent laborers, who will be thrown upon society by the reorganization of the Union.”7

Catto became a member and officer of the Banneker Institute, a black literary society for Philadelphia’s intellectual elite. Besides discussing scholarly subjects such as philosophy and mathematics, Banneker members debated social-justice issues such as emancipation, equal wages, voting rights, and Republican Party politics. Banned from membership for many years in Philadelphia’s City-Wide Congress of Literary Societies, Catto’s eloquent petition finally got the Bannekers admitted. Catto also integrated the Franklin Institute, a major center for science and education. When the white dean of the Jefferson Medical College objected to black membership and threatened to cancel his lecture, Catto persuaded the Institute board to hold firm against racism.

Despite black military service and the post-war Amendments, discrimination persisted and African Americans were banned from Philadelphia streetcars. Ignored in his public appeals, Catto resorted to civil disobedience on May 18, 1865. When ordered to leave a streetcar, he refused and explained his reasoning. The conductor unhitched the car and left Catto sitting there alone all night. In the morning, a crowd and the press gathered, and the injustice was publicized. At a Union League meeting to protest the forcible ejection of several black women and children, Catto presented the following Resolution: “That we earnestly and unitedly protest against the proscription which excludes us from the city cars, as an outrage against the enlightened civilization of the age.”8

Unable to budge streetcar operators, Catto resorted to the Pennsylvania legislature. Enlisting the help of Republican Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens and William D. Kelley, Catto devised a “Bill of Rights” for public transportation, which was adopted into law in 1867. When Catto’s fiancée, the renowned educator Carrie Le Count, was subsequently barred from a streetcar, she sued and won, and the operators finally gave in. What Rosa Parks accomplished in desegregating buses in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955, Catto and Le Count achieved ninety years earlier for Philadelphia streetcars.

Through baseball Octavius Catto pursued yet another avenue for black civil rights.9 A star player on his Institute for Colored Youth baseball team, Catto loved playing the game, but he wanted something more. In 1866, he co-founded and became the captain and star infielder for the Pythian Base Ball Club, tapping players from his ICY, Banneker Institute, and Equal Rights League associates. Originally named the Independent Ball Club, many of the players belonged to the Knights of Pythias Lodge, and thus they became the Pythians (derived from a mythical priestess at the Greek Temple of Apollo). Besides Catto, the Pythian leadership included other prominent blacks who emerged from Underground Railroad families. Club president James W. Purnell worked with abolitionists John Brown and Martin Delany, and vice president Raymond W. Burr was descended from American revolutionary Aaron Burr and was the son of a prominent black activist.

While only the second black team in Philadelphia after the Excelsiors, the Pythians quickly dominated. While they lost their first game to the visiting Bachelors, a black team from Albany, New York, they ended with a 9-1 record and acclaim as the best black team in Philadelphia and perhaps the nation. Black teams began to proliferate, such as the Monitors of Long Island, the Blue Skies of Camden, the Monrovia of Harrisburg, and the Uniques of Chicago.

The Pythian games against Washington’s black teams were particularly spectacular and a boon to black pride. The contests were covered sympathetically by white reporters and white ballplayers watched the games. They drew big crowds and black leaders from both cities, including Frederick Douglass, who watched his sons play.10 Frederick Douglass, Jr. was one of the founders of the Alerts Base Ball Club of Washington, D.C. Charles Douglass became a clerk with the Freedman’s Bureau in Washington, and played third base for the Alerts, and then joined — as a player and eventual president — the city’s other black team, the Mutuals. His father was made an honorary team member.11

In 1867, the “Pyths” became even stronger by recruiting players from other black teams. Led by Catto, they won 10 of 13 games that year and went undefeated in 1868. Catto scored 59 runs in those two seasons and the club report claimed the team “performed their labors with zeal and with an ardent desire to do all in their power to sustain our character and reputation as a base ball club and as an association of gentlemen.”12

While winning games was rewarding, Catto pursued baseball for loftier goals. He sought equal participation and recognition for blacks, and believed that baseball “built community ties, pushed racial boundaries, and established local and national networks of support.”13 Catto sought to lure and organize young black men, and baseball was the best vehicle for doing so. For the Pythians he drew from middle class blacks from cultural and civic institutions who, if not already activists for black equality, could be enlisted in the cause. Baseball was a vehicle for black self-improvement, and a site where African Americans could demonstrate their skills and independence, as well as their right to full citizenship. The national pastime could promote high moral character and good health habits among the black populace.

When he traveled the black baseball circuit in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic (often to towns that had provided safe houses on the Underground Railroad), Catto spoke to players and fans of the opposing teams about current political issues and built alliances for black rights. The games were played with a spirit of friendship, and were followed by meals and parties uniting both visiting and home teams. Communication was enhanced among black communities and more young African American leaders were spawned. Shut out from other institutions, sports and politics were closely linked for black athletes.

Besides its activist uses, Pythian baseball helped make Philadelphia a major hub for the future of Negro League baseball. And it also helped inspire a role for black women in baseball. Observing the success of black teams, John Lang — an enterprising white barber — established three teams of black women, two of which survived as the Dolly Vardens. Their first game drew a large, enthusiastic crowd, and while ultimately viewed as a novelty, the women were applauded for their toughness and surprising skills. With most black women relegated to domestic labor, these ballplayers broke the mold and bravely took some first steps on the road to equality.

Promoting black teams, even black women teams, was a boon for African American institutions and civil rights organizing, but Catto had more ambitious plans. While Charles Douglass remained active in Washington baseball into the 1870s, he focused mainly on access. Despite the Civil War Amendments, black teams were often blocked from equal access to baseball resources and fields. Catto, on the other hand, sought integration on the baseball diamond, as a vehicle of cultural assimilation for blacks into white society.

In Philadelphia, Catto was able to secure accounts with the white A.J. Reach Sporting Goods Company, and schedule Pythian games at white fields, such as that maintained by the city’s white Athletics club. After the Pythians’ great 1867 season, Catto petitioned the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) for membership. He wanted his black team accepted as an equal member in the otherwise all-white league. Despite support from the Athletics at the Harrisburg convention, the Pythians got a dose of reality. They were denied membership (and even a vote) while 265 new white teams were all admitted. A few days later the Pythians beat the black Moravians from Harrisburg, 59-27, and Catto hit a home run.

Since the NABBP’s national convention would be held later that year in Philadelphia, Catto mounted another campaign. Dubbed “Catto’s Proposal,” the white Athletics delegates continued their support. Even so, the Pythians were again denied. The official explanation indicated that: “If colored clubs were admitted there would be, in all probability, some division of feeling, whereas by excluding them no injury would result to anyone.”14 Colored clubs were defined as any team with “one or more colored players.”

While the Pennsylvania chapter rejected the Pythians by a non-decision, the national NABBP denial was an open vote. Although the barrier had long existed, it had never been formally acknowledged before. Now a color line had been laid down publicly, which would not be lifted for another 80 years: “[T]he unwritten rule of baseball was now written nationwide.”15 It was a terrible lost opportunity for baseball and the nation, mimicking the dashed dreams of the broader Reconstruction civil rights movement. For many European immigrants, playing “America’s game” was often a route to cultural integration, but it had been denied to African Americans.

The failure to integrate black baseball clubs was obviously motivated by white racism, and perhaps a bit of anger against Catto, the militant equal rights agitator. But the Pythians exclusion from the NABBP was also the best way “to keep out of the Convention the discussion of any subject having a political bearing.”16 The “politics” involved the post-war relations between the Northern and Southern states. To reconcile the Union, common denominators were sought, and baseball emerged as a potential healing balm and vehicle of reunification. With the game’s great popularity, both North and South, contests on the ballfield would replace conflicts on the battlefield. This required amateur, and then professional, baseball leagues to set inviting terms for the admission of Southern clubs. Leagues allowing black teams would be unacceptable to Southern ballplayers. Ironically, as Ryan Swanson notes in his book, When Baseball Went White, the game’s popularity put it in a position to reject blacks. Baseball would help heal North-South divisions, but would have to maintain white-black divisions in order to do so.17

Some black leaders couldn’t see the significance of baseball for the struggle for racial equality. William Still, the great abolitionist and Underground Railroad leader, wrote the Pythians that: “Our kin in the South . . . have claims too great and pressing for frivolous amusements.”18 But Catto persisted, sensing the game’s eventual value as a wedge against racial discrimination. After the NABBP rejection, he shifted his strategy. The Pythians might be excluded from white leagues but they could at least break another barrier: playing a white team. Competing against “our white brethren” on a “field of green” would force whites to take racial equality seriously.

When pressed to play African Americans, white ballplayers had mixed feelings. Aside from prejudice, they felt that if they won, it would be expected and if they lost, their superiority would be called into question. One white reporter wondered whether blacks made better ballplayers than whites, and “in hot weather they play a stronger game.”19 Would a white club take the risk?

The Pythians had an advocate in the white publisher, Thomas Fitzgerald. A founder of Philadelphia’s Athletics Ball Club, he had some clout in baseball and city politics. Progressive on race relations, Fitzgerald used his newspaper, City Item, to relentlessly argue for universal voting rights. Soon he was ousted from the Athletics for his views: It was one thing to promote racial progress in the South, but black voting rights in Philadelphia went too far. Even so, Fitzgerald used his newspaper to lobby for a black-white baseball contest. In 1869, he wrote ardently about the black teams, and had a particular fondness for Catto and the Pythians. He asked: “Who will put the ball in motion?” Fitzgerald, who some now view as a forerunner of Branch Rickey, challenged the Athletics, in particular. Then in a letter attributed to Catto, a writer asked: “Why is it that the Athletics will not play the colored baseball club called the Pythians? Are they afraid of them? As I hear it the Pythians are very strong. I think it is quite possible that the apprehension of being beaten by them is the real cause. Fie. Fie! I call on the Athletics to play the Pythians forthwith!”20

In August 1869, the white Masonics team agreed to play the Pythians, claiming that: “There is a desire on the part of a great majority of the admirers of the game of base ball to have some club, composed of players of the Caucasian race, play a game with the famous Pythian club, composed of colored gentlemen.”21 Suddenly other white clubs expressed interest: the Keystones, the Experts, the Franklins, even the Athletics. Yet it was all talk, as fears rose about being the first to lose to a black team.

But Fitzgerald and Catto persisted, and finally the challenge was accepted by the Olympic club, fittingly the nation’s oldest team. Aside from Fitzgerald’s influence, Catto had nurtured social and political relationships with white businessmen and white ballplayers. This made a difference even though most Olympic players were hardcore Democrats while Catto was a Republican black rights advocate.

On September 3, 1869, the Pythians met the Olympics on the latter’s home field, and Fitzgerald served as the game’s umpire.22 Ready to watch the unthinkable, a large and enthusiastic crowd of black and white fans looked on, the Olympics’ biggest crowd since playing the nation’s first professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, earlier that year. The Pythians took an early lead but their star pitcher, John Cannon, was injured and couldn’t give his best game. Back then, with only one umpire on the field, it was left to the players themselves to call safes and outs. The umpire was limited to hearing appeals when a team thought there was a bad call. The Pythians decided beforehand not to argue any plays. Any appeals would amount to a black man challenging a white man’s word in front of 5,000 people. The Pythians “acquitted themselves in a very creditable manner,” but lost the game 44-23. The next day’s newspapers applauded the Pythians’ gentlemanly play, and noted that had the Pythians challenged a series of bad calls, they might have won.

The New York Times described the contest as “A Novel Game in Philadelphia.”23 But it was much more than that. It was the first recorded game between formal black and white teams. To complete the picture, however, the Pythians wanted a victory to show that black ballplayers were as good as white ballplayers. Thus, on October 16, 1869, the Pythians defeated the white City Item Club, 27-17, and a form of equality was achieved on the diamond.

The Pythian games bridged racial divides, and inter-racial contests sprung up throughout the Northeast. The black Resolutes played the white Resolutes in Boston, for example, and the black Alerts met the white Olympics of Washington, D.C. on a field overlooking the White House. In subsequent decades, when blacks and whites lived, worked, socialized, studied, and worshiped separately, the ball field was among the few places where the races mixed. It was a site for dispelling stereotypes, and for blacks to achieve fair treatment and an opportunity to prove themselves. The sport’s immense popularity helped drive the civil rights movement forward.

Catto wasn’t done crusading. In his baseball travels and equal-rights campaigns throughout the Northeast, he valued one right above all others: the right to vote. Thus he was a ceaseless advocate for the 15th Amendment, for whose passage in 1870 Catto deserves a lot of credit. In Pennsylvania, free blacks had been denied the vote in the state’s 1838 constitution, and thus it was a particular triumph when the state adopted the Amendment. At an event honoring his role in ratification, Catto said: “There must come a change, one now in the process of completion which shall force upon this nation not so much for the good of the black man as for our own industrial welfare.”24 In the South many emancipated blacks were already voting and even holding office while some Northern states were still limiting the vote to white men. Catto continued his travels to get the Amendment enforced and to turn out black voters. For this, he became the target of threats.

In Philadelphia, blacks were concentrated in a neighborhood adjoining an Irish community. The Irish district was strongly Democratic, and controlled by a political machine that was key to Democratic Party victories citywide. Black voting was viewed as a threat to its power and economic well-being since African Americans were dedicated to the “party of Lincoln:” the Republicans. The Irish machine responded with intimidation against black voters, abetted by Philadelphia police officers, who were predominantly Irish themselves and allied to the Democratic mayor.

Violence against blacks during the 1871 mayoral election was particularly rampant. The night before, on October 9, two blacks were beaten and shot, one fatally. Despite the intimidation, Catto rallied black voters to show up at the polls. Seeking to vote himself, Catto was nearing his home when he passed two men, one of whom turned around and shot him, running away, in front of a passing streetcar filled with blacks and whites. Catto raised his own gun too late and died immediately, a martyr to racism at age 32.25 He was one of ten black men shot that day yet news of Catto’s death spread quickly and the Republican candidate easily won the mayoral election. Years later, the black radical W.E.B. DuBois would observe: “And so closed the career of a man of splendid equipment, rare force of character, whose life was so interwoven with all that was good about us, as to make it stand out in bold relief, as a pattern for those who have followed after.”26

Violence against blacks during the 1871 mayoral election was particularly rampant. The night before, on October 9, two blacks were beaten and shot, one fatally. Despite the intimidation, Catto rallied black voters to show up at the polls. Seeking to vote himself, Catto was nearing his home when he passed two men, one of whom turned around and shot him, running away, in front of a passing streetcar filled with blacks and whites. Catto raised his own gun too late and died immediately, a martyr to racism at age 32.25 He was one of ten black men shot that day yet news of Catto’s death spread quickly and the Republican candidate easily won the mayoral election. Years later, the black radical W.E.B. DuBois would observe: “And so closed the career of a man of splendid equipment, rare force of character, whose life was so interwoven with all that was good about us, as to make it stand out in bold relief, as a pattern for those who have followed after.”26

Even whites were outraged at Catto’s murder in his quest for civil rights. His funeral procession was the largest since Lincoln’s assassination and unprecedented for a black man. Over the three-mile route, tens of thousands of black and white Philadelphians watched in reverence for a fallen hero, as more than 125 carriages paraded by, containing Congressmen, military leaders, local politicians, students, colleagues, soldiers, ballplayers, and fellow civil rights activists. An Irish thug, Frank Kelly, was the known assassin, but with police assistance he escaped and wasn’t arrested for another seven years, when he was extradited from Chicago. In 1877, despite many eyewitnesses, Kelly was acquitted by an all-white jury.

Catto’s assassination left a mixed legacy. In the short run, it broke the Democratic Party machine, elevated the black vote, and redirected resources to the African American community. Republican political clubs flourished, and black candidates were elected to some offices. Catto served as an inspiration for blacks around the nation. In the long run, however, in the absence of a charismatic leader, the Equal Rights League stalled and black militant behavior declined by the late 1870s and the end of Reconstruction. With the emergence of Jim Crow, most blacks adopted a defensive posture and — by the end of the century — a self-help strategy advocated by Booker T. Washington.

A similar, self-sufficient development arose in baseball. In Philadelphia, the Pythians continued playing after Catto’s death through the 1870s and 1880s. Rather than resume the battle to enter white Organized Baseball leagues, it joined with other black clubs to begin building separate amateur, and then professional, baseball institutions of their own. In 1887, the Pythians were charter members of the National Colored Base Ball League (NCBBL). While the association folded, it demonstrated the black community’s determination to mirror white leagues of their own, and was the precursor of the Negro Leagues of the next century. In the meantime, black clubs operated independently and proliferated. Philadelphia had become a particular hotbed for the development and continuation of black baseball, and the Pythians became an inspiration for future black players and teams.

In the early years after Catto’s death, his name was memorialized at schools, university dorms, Masonic lodges, and other civic organizations. Thereafter he was largely forgotten until the last couple of decades, when annual remembrances, new headstones, and an Octavius Catto Award were inaugurated.27 Catto was also recognized by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Most notable, on September 26, 2017, a 12-foot bronze statue of Catto, entitled “Quest for Parity,” was erected and dedicated at Philadelphia’s City Hall, 140 years after his death. Philadelphia has 1,700 public statues; Catto’s is the first for an African American.28 The memorial comes at a time when cities such as Charlottesville and New Orleans have removed statues of Confederate generals and other racists, and have faced a right-wing backlash. In contrast, adding the Catto memorial begins to redress the balance and makes a positive statement against racism. Lamenting our historical amnesia, Philadelphia’s white mayor, Jim Kenney, was the driving force behind the Catto statue: “How in God’s name did I not know this man? He was the Dr. King and Jackie Robinson of his day.”29

Most notable, on September 26, 2017, a 12-foot bronze statue of Catto, entitled “Quest for Parity,” was erected and dedicated at Philadelphia’s City Hall, 140 years after his death. Philadelphia has 1,700 public statues; Catto’s is the first for an African American.28 The memorial comes at a time when cities such as Charlottesville and New Orleans have removed statues of Confederate generals and other racists, and have faced a right-wing backlash. In contrast, adding the Catto memorial begins to redress the balance and makes a positive statement against racism. Lamenting our historical amnesia, Philadelphia’s white mayor, Jim Kenney, was the driving force behind the Catto statue: “How in God’s name did I not know this man? He was the Dr. King and Jackie Robinson of his day.”29

In their biography of Octavius Catto, Tasting Freedom, Daniel Biddle and Murray Dubin write: “Historical memory is often short-lived. We know of no moment when Rosa Parks’s elders told her the story of Carrie Le Count [who tried to board a white streetcar]. Nor are we aware of anyone describing Catto’s streetcar tactics to Martin Luther King, Jr. . . . Second baseman Jackie Robinson probably never heard of second baseman Octavius Catto. But there remain intriguing links between Catto’s band of brothers and sisters, and modern times.”30

National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick launched a protest against police brutality and racial injustice in America in 2016. By “taking a knee” during the national anthem, Kaepernick has expressed his solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, and inspired other athletes (both black and white) to follow his lead, despite being condemned by President Donald Trump and white supremacists as unpatriotic dissidents. Sports, we’re told, must remain separate from politics. Yet they’re inevitably political, even in their silence. When athletes use their First Amendment right to speak out, it can provoke a valuable dialogue about race relations. Kaepernick continues a tradition upheld previously by John Carlos, Tommie Smith, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Muhammad Ali in their Olympic and Vietnam War protests. And in his final days, Jackie Robinson, like Kaepernick, refused to stand for the national anthem. Yet all of these activist-athletes stand on the shoulders of Octavius Catto, who set the tone for how athletes express their social consciousness.

Facing death threats and his own possible martyrdom, Kaepernick’s protest against black murders echoes Catto’s experience. As Kevin Rossi observes, Catto was an athlete and the victim of a racially motivated murder. Anticipating the lament of the current “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” movement, Catto’s “hands were up, he was running away, and his murderer never spent time behind bars for the crime.”31 Kaepernick uses football to protest racial injustices, and before his death, Catto used baseball for the same ends. Despite the call to separate sports and politics, “the heroes are often the ones who bridge the gap in the name of social change.”32 Octavius Catto paved the way.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Chris Rainey and Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Sandy Hingston, “13 Things You Might Not Know About Octavius Catto,” Philadelphia, June 10, 2016 (https://www.phillymag.com/news/2016/06/10/octavius-catto-memorial/).

2 Hingston, 2016.

3 Andy Waskie, “Octavius Catto Biography,” General Meade Society of Philadelphia (https://generalmeadesociety.org/octavius-catto-biography/).

4 Editors, “Catto Addresses State House in Philadelphia,” Christian Recorder, April 22, 1865.

5 Euell A. Nielsen, “Octavius Valentine Catto (1839-1871),” Black Past, November 2, 2015 (https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/octavius-valentine-catto-1839-1871/).

6 John N. Mitchell, “Octavius V. Catto Receives Long Overdue Honor,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 22, 2017 (https://www.phillytrib.com/news/octavius-v-catto-receives-long-overdue-honor/article_4d45c475-20eb-5f63-bfc5-0cc9c67537bd.html).

7 Waskie, “Octavius Catto Biography.”

8 Nielsen, “Octavius Valentine Catto (1839-1971).”

9 Matt Albertson, “Race and Baseball in Philadelphia, Part 1: Octavius Catto and the Pythian Base Ball Club,” Philliedelphia, February 11, 2016 (https://www.philliedelphia.com/2016/02/race-and-baseball-in-philadelphia-part-1-octavius-catto.html).

10 Jerrold I. Casway, “Octavius Catto and the Pythians of Philadelphia,” Phindie, March 21, 2010 (http://phindie.com/octavius-catto-and-the-pythians-of-philadelphia/).

11 George Kirsch, “Blacks, Baseball and the Civil War,” New York Times, September 23, 2014 (https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/09/23/blacks-baseball-and-the-civil-war/).

12 Patrick Gordon, “Octavius Catto, the Pythians, and Early Black Baseball in Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Baseball Review, July 18, 2016 (http://www.philadelphiabaseballreview.com/2016/07/octavius-catto-pythians-and-early-black.html).

13 “Playing for Keeps: The Pythian Base Ball Club of Philadelphia,” Historical Society of Pennsylvania (http://www.hsp.org/node/2937); Jeff Laing, “Philadelphia, October 1866: The Center of the Baseball Universe,” The National Pastime (2013) (https://sabr.org/research/philadelphia-october-1866-center-baseball-universe).

14 “Forging Citizenship and Opportunity — Octavius Catto’s Legacy,” Independence Hall Association (https://catto.ushistory.org/) (last accessed July 2, 2019).

15 Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin, Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010), 368. While blacks were banned from white amateur baseball leagues by this decision, a few blacks were able to buck the ban when the professional leagues began in 1871, on minor league teams and even — in the case of Fleet and Welday Walker — on a major league team in the 1880s. These were rare exceptions and the resistance to blacks persisted. The major leagues imposed the ban in 1884 and the minor leagues in 1889, and not until 1946 (with Jackie Robinson) would blacks be allowed back into organized baseball.

16 Daryl Russell Grigsby, Celebrating Ourselves: African Americans and the Promise of Baseball (Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing, 2010), 33.

17 Ryan Swanson, When Baseball Went White: Reconstruction, Reconciliation, and Dreams of A National Pastime (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 198.

18 Rachel Wyman, “The Philadelphia Catto: Bridging the Racial Gap in the City of Brotherly Love,” Union College Honors Thesis (Schenectady, NY: 2016), 100.

19 Jerrold I. Casway, “September 3, 1869: Inter-Racial Baseball in Philadelphia,” SABR (https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-3-1869-inter-racial-baseball-philadelphia).

20 Stephen Segal, “An Unbreakable Game: Baseball and Its Inability to Bring About Equality during Reconstruction,” The Historian, 74:3 (Fall 2012), 467-494.

21 Biddle and Dubin, Tasting Freedom, 373.

22 Ryan Whirty, “Philadelphia’s Pythians Made Baseball History in the 1800s,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 19, 2015 (https://www.inquirer.com/philly/sports/phillies/Philadelphias_Pythians_made_baseball_history_in_1800s.html).

23 Biddle and Dubin, Tasting Freedom, 375.

24 Jerrold I. Casway, The Culture and Ethnicity of Nineteenth Century Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 33.

25 Aaron X. Smith, “The Murder of Octavius Catto” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (2015) (https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/murder-of-octavius-catto/).

26 Casway, The Culture and Ethnicity, 38.

27 Mark Rothenberg, “Fighting for Equality on the Baseball Grounds,” National Baseball Hall of Fame (https://baseballhall.org/discover/octavius-catto-philadelphia-black-baseball) (last accessed July 2, 2019).

28 Linn Washington, “Honoring Octavius V. Catto: Another History Lesson Trump Will Ignore,” Counterpunch, September 29, 2017 (https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/09/29/honoring-octavius-v-catto-another-history-lesson-trump-will-ignore/); Stephan Salisbury, “A Monument at Last for Octavius Catto, Who Changed Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 2017 (https://www.inquirer.com/philly/entertainment/arts/a-monument-at-last-for-octavius-catto-the-activist-who-changed-philadelphia-20170925.html).

29 Vladimir Duthiers, “Octavius Valentine Catto Honored in Philadelphia,” CBS News, September 26, 2017 (https://www.cbsnews.com/news/octavius-valentine-catto-receives-special-honor-in-philadelphia/).

30 Biddle and Dubin, Tasting Freedom, 473-474.

31 Kevin Rossi, “Octavius Catto, Colin Kaepernick, and Athlete-Activists Turned Martyrs,” Sport in American History, October 13, 2016 (https://ussporthistory.com/2016/10/13/octavius-catto-colin-kaepernick-athlete-activists-turned-martyrs/).

32 Christopher Norris, “Black Athlete and Activist Enshrined Amid Debate on Race and Sports,” The Good Man Project, September 26, 2017 (https://goodmenproject.com/featured-content/black-athlete-and-activist-enshrined-amid-debate-on-race-and-sports-cnorris/).

Full Name

Octavius Catto

Born

February 22, 1839 at Charleston, SC (US)

Died

October 10, 1871 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.