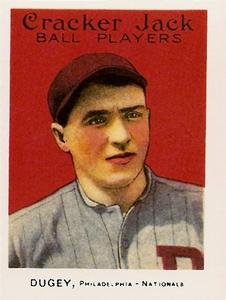

Oscar Dugey

Oscar Dugey, a utility player, was called “the luckiest kid in baseball” after playing on two straight pennant winners, in 1914 and 1915. One of the best infielders to come out of the Texas League in the 20th century’s first two decades, the 5-foot 8, 160-pound right-hander hit just .194 in 195 games during his six years with the Boston Braves and Philadelphia Phillies. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner, Dugey played in only 82 games as an infielder/outfielder. Baseball Magazine called him a “brainy man…. [who is] only a fair fielder, a weak hitter and has a none-too-strong arm.” He was at his best on the basepaths, where Baseball Magazine’s William Phelon described him as one “who can run like the devil on a wheel.” Sporting Life said that Dugey “comes up with sensational work when sensational work is needed. [He] can take the hundred to one shots and get away with them. His reckless base running would be the ruin of any other player. … Jake takes the long chances and wins.”

Oscar Dugey, a utility player, was called “the luckiest kid in baseball” after playing on two straight pennant winners, in 1914 and 1915. One of the best infielders to come out of the Texas League in the 20th century’s first two decades, the 5-foot 8, 160-pound right-hander hit just .194 in 195 games during his six years with the Boston Braves and Philadelphia Phillies. Used primarily as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner, Dugey played in only 82 games as an infielder/outfielder. Baseball Magazine called him a “brainy man…. [who is] only a fair fielder, a weak hitter and has a none-too-strong arm.” He was at his best on the basepaths, where Baseball Magazine’s William Phelon described him as one “who can run like the devil on a wheel.” Sporting Life said that Dugey “comes up with sensational work when sensational work is needed. [He] can take the hundred to one shots and get away with them. His reckless base running would be the ruin of any other player. … Jake takes the long chances and wins.”

Brainy, quick-witted, and shrewd, Jake Dugey made his mark in the dugout, first as an aide to George Stallings on the 1914 “Miracle Braves,” then with Pat Moran’s Phillies, and later as a coach with Bill Killefer’s Chicago Cubs. The Boston Herald said, “Oscar knows baseball as played in the National League as even Pat Moran or John McGraw. You can say no more.” The Wilkes-Barre Times said Dugey “knows more baseball than lots of veterans nearly twice his age.” Renowned as a bench jockey, Dugey was also “one of the craftiest interpreters of signals in either major league,” according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

The third of six children born to Oscar J. and Mattie Belle (Greene) Dugey, Oscar Joseph Dugey was born on October 25, 1887, in the East Texas town of Palestine. His father was born and raised on a Patterson, Louisiana, sugar plantation owned by his mother and grandfather. He married Mattie, a native of Louisville, Kentucky, in Palestine in July 1879. She was said to be a descendant of Virginia’s Robert E. Lee family. A year later he was working as a grocery clerk; by the turn of the century, the elder Dugey, known as O.J., was one of Anderson County’s most prominent citizens.

In December 1907, the Palestine Daily Herald called O.J. “perhaps the oldest Palestine merchant”; he was the proprietor of the Original Sample Store, a dry goods establishment on Main Street. He was also one of the founders of the Palestine Salt and Coal Company and a powerful member of the Democratic Party in Texas. During the gubernatorial campaign of 1906, O.J. stumped for Thomas M. Campbell, leading the Daily Herald to dub Dugey “the most demonstrative Campbell man in Texas.” When the governor-elect offered him an appointment in his new administration, O.J. turned it down, saying that he had supported Campbell “from principle and not for office.” He continued to be active in local affairs, among others petitioning for new public roads and canvassing businessmen for donations for a new ballpark. Unfortunately, O.J.’s business affairs went awry, causing him to file for bankruptcy shortly before Christmas 1907. A few days later, on January 6, 1908, he died suddenly at his home.

Mattie Dugey didn’t live in her husband’s shadow and outlived him by nearly 48 years. According to the Palestine Daily Herald, she was “a brilliant [play] writer”; her obituary in the Dallas Morning News noted that “several of them [are] on file at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.” In 1906, she traveled to Dallas to try to sell a play entitled Louisiana Before the War. The Morning News featured a photo of her in 1924 when there was a reading of Maelstrom, a work that “received much favorable mention.” Mrs. Dugey moved to Dallas in 1912, a few years after O.J.’s death and after selling the family home at 1211 S. Sycamore. The Daily Herald called it “one of the prettiest homes in Palestine.”

Oscar Dugey learned baseball from his brother Elmo, who was four years older. Elmo was labeled by the Fort Worth Star-Telegram as “almost as good as his brother [Oscar]” in 1912 and was reported to have “received a number of very flattering offers to go into the professional ranks, [but] has refused to consider them, and plays only for the sport and the game.” Like his brother Oscar, Elmo was a second baseman. He managed the Washer Brothers team in the Fort Worth Commercial League and hit .356 in 1911.

According to the Palestine Daily Herald, “(Oscar) Dugey got his preliminary training in the baseball world in this city when he was a member of the Palestine champion team of a few years ago.” This might be a reference to the 1905 team, which the paper referred to as “all-professional, with the exception of little Dugey on second, who is as good as any of them.” An account of a 1-1 ten-inning tie with Tyler said, “Dugey at second made two fine stops.” In 1906, Dugey played second base for the semiprofessional Groesbeck team (31-9) of the Southwest Texas League, earning $30 a month. It was about this time that he acquired the nickname Stump. Dugey split his time in 1907 between the Tulia North Texas League semipro club (earning $50 a month) and the Palestine Elks. After a 1-0 Palestine win over Tyler in July, the Daily Herald said, “Broyles, Dugey, Hearne and Bowdon make a fast infield, and very few balls get by this quartette.” The Fort Worth Star-Telegram mentioned that Oscar was a student at Brantley-Draughon Business College in Fort Worth, probably in 1908, where he played with the student team, soon becoming a star in the local city league.

Oscar broke into Organized Baseball in July 1908 with the Waco Navigators of the Texas League. He played third base in a 3-1 win over San Antonio on July 10, batting 0-for-3. The Star-Telegram said “Dugey … played brilliantly at third base” while taking the place of player-manager Bill Yohe, who was sidelined with malaria. One of his best games was three days later, a 2-for-4 performance with a double and a run in a 4-0 victory over San Antonio. Dugey, now called “Kid” by Texas newspapers, didn’t continue his brilliant play over the rest of his 27 games, hitting .164 and fielding an unimpressive .880, posting ten errors and finishing 17th of 23 third basemen in the league.

Back with Waco in 1909 for his second of six seasons, Kid Dugey got his first taste of major-league competition in an exhibition game against New York on March 7. The Giants prevailed, 7-1, but Dugey scored the Navigators’ only run after hitting a triple in the third inning. The Daily Herald said Dugey “was the star attraction of the game, and was given an ovation by the Waco fans and made the Giants take notice of his work.”

Meanwhile, other papers were noticing Dugey’s work. In late April, the Galveston Daily News called him “a gabby but good natured piece of baggage—not excess, either, for he is one of [manager Ben] Shelton’s best men.” After a 12-5 shellacking of Dallas on May 31, the Morning News said, “This Kid Dugey seems to be some ‘pumpkins’ with the stick. He got hits three trips out of four yesterday and most of his wallops came when men were on the sacks.” By the end of the season, Dugey, who had moved from third base to second, had shown marked improvement from his first year, hitting .250 for the last-place Navigators (51-91). His fielding was only marginally better, with an .895 percentage and 51 errors in 106 games, tied for last among the 15 second basemen in the league.

Dugey had to deal with health issues early in 1910, missing part of spring training with the measles and enduring an early May spike wound so serious that a doctor from the grandstand insisted that only a quick transport to the hospital via automobile, not a trolley or horse and buggy, would do. Once he was back in the lineup, Kid hit his stride and was being carefully watched by major-league clubs. In early July, the Beaumont Enterprise and Journal noted that “Dugey is playing excellent ball for Waco. It looks as if he is due to be called to a faster team. He is wasting his talents there.” His defense was improved, as evidenced by his play in a 6-1 win over Houston on July 16. According to the Morning News, “A feature was the playing of Dugey at second, fifteen chances without an error.” A week later, in a 7-6 loss to Oklahoma City, Dugey’s offensive talents were on display as he went 3-for-3 and stole home.

By early August, last-place Waco was disposing of as many players as possible. Deals for Dugey were at the forefront, and it was reported that he was on his way to either the Chicago White Sox or the Cleveland Naps. Wilson Matthews, a former minor-league manager and then Texas League umpire, told the Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman, “Dugey is the best second baseman in the Texas League. …. He has been hitting well and has been playing grand ball with a tail-end club. … I believe that he has one of the brightest futures of any infielder in the circuit today. Youth, speed, a good batting eye, are all points in his favor.” In mid-August, the Dallas Morning News announced its Texas League All-Star team, with Dugey as the second baseman. Oscar had hit .237 in 114 games, but the Star-Telegram said “[he] is hitting at a .300 clip now and has been steadily improving for a month. … He is in the upper class of base runners.”

The deals to send Kid Dugey to the majors never materialized. Instead, he was purchased on August 22 by manager Charley Frank of the Southern Association’s first-place New Orleans Pelicans. Early reports said Dugey was setting the Southern Association afire with his hitting. He was 1-for-3 with a run in his debut, a 6-1 win over Nashville on August 28. Three days later, the Star-Telegram reported that “New Orleans is so pleased with Dugey that Charley Frank is now after [Waco’s] Jack Onslow and Harry Storch.”

New Orleans eventually cooled on Dugey as his overall game was not up to Southern Association speed; he was hitless in over half his games, and his wild throw to the plate allowed two runs to score in the first inning of a 4-0 loss to Chattanooga on September 10. When the season ended, the Pelicans (87-53) won the pennant and Kid had hit .138 in 19 games. On December 28, 1910, the Pelicans sent him back to Waco.

Appointed captain of the 1911 Navigators by manager Ellis Hardy, Dugey, now known also as Jake, had a difficult early season. On April 20, he protested an Oklahoma City runner scoring on an overthrow of first base and was ejected and fined. The next day, in a 4-3 loss, he severely broke his ankle sliding into third base and didn’t return to action until May 30. Three days later, Dugey’s two-run homer in the eighth inning was the winning blow in a 3-1 victory over Dallas. Shortly thereafter, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram was reporting that major-league scouts were hovering around Waco watching the work of Dugey and two others. On July 20, the Star-Telegram selected him as the second baseman for its midseason All-Star team. Final averages showed that Kid’s batting average had slipped to .219 in 110 games for fifth-place Waco. His fielding continued to improve, though, as he recorded a .960 percentage, placing him in the upper echelon of Texas League second basemen.

In mid-November 1911, the Star-Telegram reported that “Vic Miller … and Oscar Dugey, the clever little second sacker of the Navigators, have formed a partnership in a pool hall business down in Waco. Rumor has it that the pair are doing a grand business.”

On March 17, 1912, Dugey served notice that he was ready for major competition with a 4-for-6 exhibition-game performance against the Chicago White Sox. According to the Star-Telegram, “Dugey’s hitting was the feature.” His daring and speed on the basepaths was on exhibit on April 14 as he stole three bases in a 6-5 win over Dallas. Two weeks later, he singled in the third and then stole second, third, and home for the Navigators’ first run in a 4-1 victory over Austin.

Kid’s fielding and hitting had also improved. After a doubleheader split with Dallas on July 4, the Morning News reported that “Dugey beat down several fast drives that were labeled hits.” After a 3-1 win over Houston on July 22, the Morning News said, “Dugey’s fielding was sensational.” He was equally adept with the bat in July; in a doubleheader split with Galveston on the 18th, Kid was a combined 5-for-9 with five runs, a triple, and a home run. He was 2-for-3 with a run in a 3-0 win over Austin on the 29th. According to the Morning News, “The feature of the game was a three-base hit by Dugey, which was but little above the ground the entire distance.”

Waco’s third-place finish (82-63) was the best of Dugey’s tenure with the Navigators. His average improved to .250 in 145 games and he led the league in stolen bases with 54; he was fifth in runs with 85. On defense, he led the league in total chances at second base with 831 and posted a .951 percentage.

In 1913, Dugey’s stunning season paved the way for his rise to the majors. In 137 games at leadoff, he hit a personal best .279 (11th in the league), scored 85 runs (second), and stole a league-record 71 bases; his .955 fielding percentage was second among second basemen. Perhaps his finest game was on May 30 in a 3-2 win in 15 innings over Fort Worth. Dugey scored all of Waco’s runs, was 5-for-7 with two doubles at the plate, and stole two bases. Another stellar outing came on June 22 in a 5-0 victory against Houston; Dugey was 3-for-4 with a double, three runs scored and four stolen bases. Sporting Life said, “Dugey led the attack. … [his] sensational baserunning was the feature.” Other examples were abundant. He had at least three hits in ten other games, invariably coupled with scoring one or more runs, while stroking an extra-base hit and adding a stolen base or two. Sometimes it was just contributing a key blow; on June 2, his home run to deep left in the sixth was all Waco needed in a 2-0 win over Fort Worth.

The first indication that Jake was about to move up to the majors came in mid-June when Sporting Life reported that umpire Wilson Matthews had offered the Waco Base Ball Association $2,000 for Dugey, an offer that was neither accepted nor declined. The paper said, “It is rumored that Matthews wants Dugey for the Philadelphia Americans.” The answer came on August 13 when Waco sold him to the National League’s Boston Braves for $2,000, to be effective at the end of the Texas League season.

In reviewing Dugey’s game after the sale, Sporting Life said, “Dugey has been the leader of the Waco attack since he first became a member of the squad … [and] hitting close to a .400 clip for the past few games. No Waco player has ever achieved a greater popularity than ‘Stumpy.’ [H]e has earned this place. … His defensive work is on a line with his attack. A large number of the most thrilling catches of Texas League games have been executed by [Dugey].”

Dugey made his major league debut in the first game of a doubleheader in Cincinnati on September 13. Reds manager Joe Tinker and Boston shortstop Rabbit Maranville had a first-inning fistfight and were escorted off the field by the umpires; Dugey took Maranville’s place and was 2-for-5 with a run against Reds pitcher Red Ames. Cincinnati won the game 5-4 in 11 innings. Dugey also played in the darkness-shortened second game, a 1-0 (5 innings) Boston win, and was hitless in two at-bats. He had ten chances in the field in the two contests and recorded two errors. Two days later, the Boston Globe said, “Dugey …. made a good impression.” He made three other appearances for the 1913 Braves, two as a pinch-hitter, drawing a walk and striking out. His average for five games was .250.

In December 1913, the Morning News reported that Jake Dugey had visited relatives in Dallas and was on his way to Shreveport to visit his sister. A few days later, the Portland Oregonian said that Dugey would be spending the winter in Los Angeles, one of 16 major-league players who would vacation in the area.

In February 1914, the Boston Globe labeled Dugey “an infielder of considerable promise,” but his real on-the-field value was as a substitute for Johnny Evers at second; otherwise, he was a utility outfielder/pinch-hitter/pinch-runner. Given the opportunity, he was capable of making a contribution; Braves manager George Stallings inserted him as a pinch-hitter in the sixth inning of a scoreless game in Pittsburgh on May 12 and Jake came through with an RBI single. The game ended in a 1-1 tie after ten innings because of rain. On July 13, Dugey’s two-run homer in the top of the 12th inning, his only four-bagger in the majors, was the winning margin in an 8-7 win in St. Louis. Sporting Life called the home run “lucky,” saying, “[it] ordinarily would have been a good double, but Dolan fielded it poorly and it rolled to the fence.” Another key hit came on September 11 against Philadelphia. With the Braves trailing by a run going into the ninth, manager Stallings sent Dugey to the plate as a pinch-hitter. He singled, moved to second on a wild pitch, advanced to third on Possum Whitted’s single, and scored the tying run on Maranville’s sacrifice fly. Whitted scored the winning run in the 6-5 victory. The win enabled Boston to stay 2½ games ahead of New York. Dugey hit .193 in 58 games and only twice had more than one hit in a game.

In early August, Sporting Life reported that Dugey and Rabbit Maranville had met on July 22 with officials of the Pittsburgh Federal League club, which wanted both to sign contracts and immediately jump to their team. The paper said, “The two players were willing to sign with the Pittsburgh Federal Club for next year, but positively refused to jump at this time.”

Jake Dugey’s off-the-field work was his biggest contribution to the worst-to-first rise of the Miracle Braves of 1914. According to author David Cataneo, “Stallings obsessively kept the dugout free of pigeons, peanut shells, gum wrappers, and bits of paper. Opposing players threw peanuts to attract pigeons. [Stallings] assigned infielder Oscar Dugey to shoo away the birds, and Dugey claimed his career was shortened by a sore arm caused by heaving pebbles at pigeons.” He was also Stallings’ “jinx-killer.” Dugey once told the Star-Telegram that Stallings hated to have strangers staring into the Braves dugout. One of Dugey’s duties was to stretch out a tarpaulin to cut off the intruders’ view. One stranger got so close that Stallings ordered Jake to “bust his nose, douse him with water, do anything you want, but get him away before he hoodoos us!” Dugey rushed away to get a bucket but returned to find that the stranger had taken the hint and left before Dugey came back.

Dugey didn’t play in the 1914 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics. As the Saturday Evening Post told it, “the defeat of the Athletics … in four straight World Series games was accomplished largely by the Boston [bench] jockeys. … Stallings hired three utility infielders, Dugey, Billy Martin, and Eddie Fitzgerald, whose chief value to the team was rattling the smug Athletics. Dugey, who had a dead arm and was never a good hitter, kept a little black book on the temperamental weaknesses of every player.” He told the Dallas Morning News in 1950, “[We] dug up more dirt on those players than anybody dreamed existed.”

Another of Dugey’s specialties was flashing and stealing signs. According to Dugey, “The A’s were so cocky they didn’t even bother to scout us Braves. Chief Bender figured they were about the best sign-stealers in the business. We gave him plenty to work on. The Braves had three or four completely different sets of signals. We’d use one set about two or three innings and then switch. The Athletics nearly went crazy trying to get those signals down. Two or three players were picked off at second when they got too busy watching for signals instead of our pitchers.”

After the sweep, it was a busy winter for Jake and the rest of the Braves. Some of the players remained in New England for the fall and played basketball. Sporting Life said that “Evers is … a star at the cage game, and Maranville … is also a wonder at this sport. Dugey is reported to be the best basket ball player in New England.” Then there was the matter of spending his World Series winners’ share — $2,812; Dugey used his money to buy a farm near his home in Palestine. He also visited friends and family in Dallas during the Christmas holidays. According to the Morning News, Dugey “has a host of friends, in fandom and out of it, who are watching his career.” An avid hunter, fisherman, and trap shooter, Dugey hosted a deer hunt for several players in Pittsburg, Texas, after the Christmas holidays.

Dugey was on a hunting trip near Shreveport on February 13, 1915, when he received a telegram from Braves president James E. Gaffney informing him that he been traded to the Philadelphia Phillies three days earlier as part of a December 24 deal that sent Sherry Magee to Boston. Philadelphia also received Possum Whitted on February 14.

A Star-Telegram story said Dugey didn’t like the idea of leaving a championship club for an also-ran and let Stallings and Phillies manager Pat Moran know it. It was during spring training that Jake asked Whitted why he was sent to Philadelphia; Whitted told him it was because he had recommended Dugey to Moran. Dugey then politely informed Whitted that if Boston won the pennant, he (Dugey) would ship all of his belongings to Whitted’s North Carolina home and spend the winter as a guest. “You’re on,” was Whitted’s reply, “but suppose we win the pennant, then what?” “Not a chance,” Dugey said, “but if we do, I’ll give you $50 to spend for a hunting dog.”

After spending spring training laid up with injuries, Jake made his first appearance at second base for Philadelphia on April 28, going hitless in a 3-0 win over Brooklyn. He had another start five days later, in a 3-2 loss to New York, hitting 2-for-4 with a double and a steal of home. For the season, Dugey hit .154 in 42 games, mostly as a pinch-hitter and pinch-runner, appearing in just 14 games as a second baseman.

According to the Wilkes-Barre Times, “Pat Moran made him his field lieutenant and his work on the coaching line was pretty smooth.” Phillies pitcher Al Demaree called Dugey “one of the cleverest in the game at grabbing signs from the pitcher.” He was able to recognize the type of pitch from the pitcher’s grip. “By a pre-arranged word-sign … any time Dugey shouted, ‘Make it good’ to the hitter, he knew a curve ball was coming. If [he] told him to ‘crack it,’ he was set for a fast ball.”

In early June, Dugey visited his mother in Shreveport. According to the Star-Telegram, she was “dangerously ill but is recovering.” He rejoined the team in St. Louis on June 7. The Phillies had a day off on September 22 during a trip to Chicago and catcher Bill Killefer took Dugey and Eddie Burns to his hometown of Paw Paw, Michigan, for the day.

Philadelphia (90-62-1) won the pennant by seven games over Boston. By September 28, Possum Whitted had a $50 check signed by Oscar Dugey and had ordered his hunting dog.

The Phillies lost the 1915 World Series 4 games to 1 to the Boston Red Sox. Jake Dugey appeared in two games as a pinch-runner; in Game Four, at Boston, Fred Luderus singled and drove in Gavvy Cravath from third with two outs in the eighth. Dugey ran for Luderus and stole second on pitcher Ernie Shore and catcher Hick Cady but was stranded a moment later when Whitted grounded out. Jake again appeared with two outs in the eighth inning of Game Five when Cravath walked and was replaced. Whitted again grounded out to end the inning. Called “one of the luckiest players in baseball” by the Washington Post for playing very little for two straight pennant-winners, Dugey pocketed his loser’s share of $2,520.17 and headed to Texas for the winter.

Shortly after the end of the season, catcher Bill Killefer and pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, then the most famous battery in baseball, joined Dugey to hunt and fish at Ferndale Lake near Leesburg, Texas. After several weeks, Alexander left for his home at St. Paul, Nebraska, with Dugey and Killefer traveling to Dallas to buy supplies, visit with their mothers, and stop by the Morning News office to visit old friends. They returned to their camp by mid-December.

By the end of July 1916, Jake Dugey had the best average on the Phillies, .385 in 19 games according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, “principally acting as an understudy [to Bert Niehoff], coacher, and morning workout man.” On August 20, the Inquirer said, “Dugey … is roosting high these days … topping the Nationalmen in hitting with a snug percentage of .333 made in 23 games. …. To be sure [he] has not made many hits, nor has he been at bat very frequently, but his six hits from eighteen trips to the rubber are sufficient to give him the lead.” Jake’s average fell to .220 in the final weeks of the season as he batted 5-for-32 the rest of the way. His .967 fielding percentage in 12 games was the best of his career.

Jake again spent the winter in Texas, mostly at Leesburg, with Killefer and Alexander joining him on October 17 for several weeks of fishing and hunting.

Dugey wasn’t happy with the contract offered by Phillies president William Baker in 1917. According to Sporting Life, “O.J. suffered a cut in his contract … but on the evidence of his fellow players and the earnest entreaty of Manager Moran, President Baker added the copeks necessary to satisfy Oscar. The Dugey person appears to be one athlete who has been vastly underestimated by both the home fans and the club managers.”

Philadelphia trained at St. Petersburg, Florida, and Dugey had a curious and peculiar way of passing time in the evening, a “sport” he called “flushing chickens.” As told by The Evening Independent, Dugey, who never married, would wait until about 10 o’clock in the evening, take a soft-drink bottle and stroll down to the private pier on the beach front. Walking along, he would soon spot a couple “spooning” and make a quick flash with the bottle, startling the couple. After walking the length of the pier and flashing his bottle several times, he would yell, “This is a private pier and no trespassing is allowed on it. You have all got to get off.” Pair by pair, the couples beat it off the pier and then Oscar would go back to the Edgewater Inn and announce that he had flushed so many chickens. According to the Independent, “If Dugey could make as many base hits as he has chased loving couples off the pier this spring he would lead the National League in batting by a big margin.”

On April 11, Opening Day, Jake (1-for-4) drove in two runs with a third-inning triple in the Phillies’ 6-5 win over Brooklyn. He had an RBI single and scored in an 8-6 victory over Chicago on May 22, enabling Philadelphia to sweep a four-game series and take the National League lead. Sometimes Dugey’s defense let the team down. On August 10, the Philadelphia Inquirer said second baseman Dugey “was shaky on pretty nearly everything that came his way. He dropped Killefer’s good throw on a Jackson steal attempt that ultimately didn’t cost anything. In the seventh King of Pittsburgh reached on Dugey’s muff and eventually scored [the only run in the contest.]” Dugey hit .194 in 44 games with the 1917 Phillies.

With the end of the season, Grover Alexander visited Dugey and his mother in Dallas; they were photographed buying Liberty Bonds at the City National Bank on October 25. After the short visit, the two went to Shreveport for a hunting trip. Dugey later went hunting in East Texas in December with Hamilton Patterson, manager of the Dallas Submarines of the Texas League.

In January, the Racine Journal- News reported that Philadelphia would not offer Dugey a contract for 1918. President Baker, who was cash-strapped and had dealt Alexander and Killefer to the Chicago Cubs in December, wasn’t in the mood to retain his sore-armed utility player and sold him to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association on April 3. Dugey had worked out with players from the Dallas Texas League squad in mid-March and joined the Saints a month later, seeing action in 15 games during April and May, hitting .137, with just two of his seven hits going for extra bases. He was released shortly thereafter.

Jake Dugey was out of Organized Baseball in 1919. Instead, he was hired as captain of the Maxwell Motor Company semipro team based in New Castle, Indiana. In February 1920, the Dallas Morning News announced its All-Time Texas League team and named Jake Dugey as the second team’s second baseman.

George Stallings brought Dugey back to the Boston Braves as a coach in 1920. The Boston Globe said Stallings “was pretty well pleased. He believes Dugey is one of the best men in this respect that he has ever had.” The Columbus Ledger-Inquirer described his role as “see[ing] that the men shape into Stallings’ system of play.” Signed as a player-coach, Dugey appeared in five games as pinch-runner, scoring two runs, for the seventh-place Braves (62-90-1).

Jake made headlines as a coach on April 20, getting into a fistfight with Brooklyn Robins outfielder Hi Myers. According to the Globe, Dugey was loudly advising pitcher Joe Oeschger to “dust them off,” as Myers had struck out with a chance to drive in a run. The normally mild-mannered Myers responded with “some uncomplimentary epithets” to Dugey and the two were soon were exchanging blows, coming to a clinch, and scuffling around on the ground. Neither was damaged but both were ejected from the game. Joe Vila, writing for the Philadelphia Inquirer, concluded that “Myer did wrong …. but Dugey …. was primarily to blame. The practice of ‘riding’ opposing ball players has been characteristic of the Braves ever since Stallings assumed the management. It isn’t clean sport and shouldn’t be tolerated. Stallings tolerates rowdy conduct, while other big league managers can produce winning teams without it.”

Stallings resigned as Boston’s manager after the 1920 season, leaving Jake Dugey without a job. In mid-April 1921, he was signed by the Chicago Cubs to assist manager Johnny Evers, thus reuniting him with his close friends Killefer and Alexander. His most noteworthy act was an ejection from a 6-5 loss at New York on July 9 for registering his disgust with ball and strike calls, picking up a glove at first base and hurling it all the way to the plate.

On July 20, Dugey was given his unconditional release by team president William Veeck. Two weeks later, Veeck fired Johnny Evers and named Killefer the new manager. Killefer told Veeck that he wanted Dugey back in the coach’s box and was willing to forgo his pay raise in order for Jake to return. The Chicago Tribune wrote that Killefer said, “Every player on the team wants Oscar back, and they are willing to chip in to pay his salary.” Veeck immediately added Jake to the roster, explaining that he had been let go “under the Evers management.” Killefer said he “believes the coach will aid the club materially in restoring the old fighting spirit.” The Cubs’ (64-89) seventh-place finish suggests that fighting spirit wasn’t enough to lift them out of the second division.

The 1922 Cubs (80-74) moved up to fifth place under Killefer and Dugey. Jake was ejected from three contests, once, in the words of the Tribune, for “loud talking from the bench” and another “for howling about two decisions on runners at the plate.” On August 1, Killefer’s mother was killed in a Michigan auto accident. Bill left the team for 12 days to be with his family and Oscar Dugey was left in charge of the club, which went 7-4-1 under his guidance.

Dugey again found himself in charge of the club in March 1923, when the Cubs were training on California’s Catalina Island. Killefer was called to Chicago to attend to his seriously ill wife and was again absent for 12 days. In August, the St. Petersburg Times said, “Dugey is doing his stuff again. … [S]tories tell of teams that found their signals were in the hands of the enemy when they played Chicago. … [They] had to change their signals several times a game, and yet they seemed to divine every kind of ball that was pitched. Fingers are pointed at Dugey. …. [T]here is nobody apter in ‘getting’ the stuff of a ball team than Dugey.”

Jake had his own bout of illness in September when he was hospitalized for ten days with tonsillitis. The 1923 Cubs (83-71) were Killefer’s best club, finishing in fourth place, 12½ games behind the champion Giants.

The 1924 Cubs got off to a good start and were in contention until late June, when Alexander’s wrist was fractured by a line drive. Without his pitching, Chicago fell out of the first division over the next two months and found itself ten games behind the Giants. The Cubs (81-72-1) finished fifth, 12 games in back of New York. On November 23, president Veeck announced that Dugey, who was on a player’s contract, would be released. According to the Tribune, Veeck said, “I like a coach who is more demonstrative in his work. I like to hear them yell on the coaching lines and display a lot of pep and spirit, and Dugey is not that kind of coach.” Norman E. Brown, writing in the New Castle News, countered by saying that “Dugey wasn’t very demonstrative with the Braves back in 1914. He made very little noise while stealing most of the signals that the National League opponents tried to flash around the field.” The News and the Tribune were both of the opinion that other big-league clubs would want him as a coach or that he would wind up managing in the Texas League.

Neither possibility materialized. Jake was next spotted attending the 1925 World Series with Killefer in Pittsburgh. Four years passed before he was mentioned in the press again; in July 1929, the Dallas Morning News noted that Dugey, who made Dallas his home, was employed as a Texas League scout for Montreal of the International League. A year later, the Olean Evening News reported that Oscar was the “constant companion and loudest rooter” for noted alcoholic Pete Alexander, who was attempting an ill-fated comeback with the Dallas Steers. “Pete has the stuff,” Oscar said, “There is not a minor league batter who can hit him when he keeps himself fit. If Pete keeps in training, he still has plenty of years to play.” Alexander’s comeback lasted five games, with a 1-2 record, 46 baserunners in 24 innings, and an 8.25 ERA.

Dugey had several jobs after he was out of Organized Baseball. A 1934 New York Times retrospective on the 1914 Braves said that he was in the electrical business in Dallas. Dallas city directories from the late 1930s and 1940s show Dugey working for the Ball Motor Company, a business that rebuilt wrecked cars. Perhaps Jake’s last connection with baseball was in March 1940, when he worked with former minor-league pitcher Roe Ikard at Harry Wanderling’s baseball camps for boys, a month-long series of conditioning, skill-based workouts, and daily practice games.

Jake Dugey spent his later years living at the Ambassador Hotel in Dallas. A March 1965 Denton Record-Chronicle article mentioned that he had suffered a stroke in 1962 that left him with impaired vision. A retired painter, he died at Parkland Hospital on January 1, 1966, after he fell and fractured his hip, an injury that was exacerbated by pneumonia and chronic lung disease. He was survived by three sisters, Dimple Whited, Gennevieve Phillips, and Virginia Marshall, and a brother, Frank. Dugey is buried at Oakland Cemetery in Dallas.

Sources

In addition to the newspapers cited in the text, the following sources were used.

Cataneo, David. Peanuts and Crackerjack: A Treasury of Baseball Legends and Lore (Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1994), 79-80.

Macht, Norman L. Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 634.

Frank, Stanley. “Rough Riders of the Dugouts,” The Saturday Evening Post Vol. 213, Issue 46 (May 17, 1941), 18, 89.

Phelon, William A. “How I Picked the Loser,” Baseball Magazine Vol. XVI, No. 2 (December 1915), 116.

Baseball-reference.com (including SABR minor league database)

Retrosheet.org

Ancestry.com

Rootsweb.com

Texashistory.unt.edu

Full Name

Oscar Joseph Dugey

Born

October 25, 1887 at Palestine, TX (USA)

Died

January 1, 1966 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.