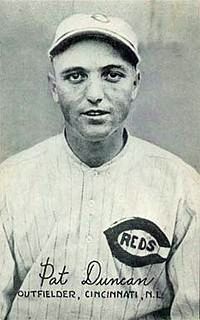

Pat Duncan

Ohio has long been known for its plentiful farmlands, its sun-baked fields, and its endless horizon. But in the southeastern section of the state the terrain is hillier, rockier, and much rougher. The richness of this area is what lies beneath the ground, whether the salt beneath Scioto County, iron ore in Lawrence County, or the once plentiful coal of Jackson County. Beneath is where men found work; and where men found work they started families. In a small town in Jackson County aptly named Coalton, Louis Baird Duncan was born on October 6, 1893, the third child of Martha and James Duncan. Louis was the second boy, with a sister, Bessie, and a brother, Charles, before him.

Ohio has long been known for its plentiful farmlands, its sun-baked fields, and its endless horizon. But in the southeastern section of the state the terrain is hillier, rockier, and much rougher. The richness of this area is what lies beneath the ground, whether the salt beneath Scioto County, iron ore in Lawrence County, or the once plentiful coal of Jackson County. Beneath is where men found work; and where men found work they started families. In a small town in Jackson County aptly named Coalton, Louis Baird Duncan was born on October 6, 1893, the third child of Martha and James Duncan. Louis was the second boy, with a sister, Bessie, and a brother, Charles, before him.

James was a coal miner, the industry that represented Jackson County’s most profitable business opportunity at the turn of the century. At that time it was assumed that a boy born in the county would be looking for work beneath the surface of the earth when he was old enough for the long, hard hours that were the earmark of the industry. In 1907 the Jackson County mines were beginning to give less coal than the prior generation provided, prompting layoffs and forcing men in the area to look elsewhere for work in the mining industry. To the west of Ohio a small, growing town in southwestern Indiana named Jasonville was of particular interest to the men who called Jackson County home.

Jasonville was a boom town, a hamlet with little civilized history and a burgeoning business in the local food chain, for the coal extracted from the ground there helped fuel the trains that were laden with Indiana limestone headed for market. There was work to be done there installing railroad switches, mine tipples, barns, blacksmith shops, engine rooms, and numerous other structures. But there was a distinct lack of manpower, and so many residents of Jackson, including James Duncan and his family, headed to Jasonville in search of work that many of the older Jasonville residents used to joke that perhaps there was only one county in Ohio and that it was named Jackson.

Since he was of Irish heritage in this era, it was neither odd nor off-putting that Louis Duncan was tagged with a nickname that reflected his lineage. By the time he was 17 he was known throughout Coalton as Pat. In Jasonville he soon began to make a name for himself as a fine ballplayer, one good enough to secure a starting slot on the Jasonville Nine and talented enough to elicit an offer from the Springfield ballclub of the Class B Central League in 1912, and 18-year-old Pat Duncan turned his back on the mines and began his career in the world of baseball.

Pat’s first foray in Organized Baseball was not one rich with experience or significant accomplishments. His journey to Springfield began in April 1912 and ended the next month without an appearance on the roster. Class B ball was evidently too challenging for the 18-year-old outfielder. Rather than return to the mines, he hooked up with the Marion/Ironton team in the Class D Ohio State League. Here, closer to the familiar territory of his youth, Duncan finally launched his pro career, finishing up the season in that league. The following winter he signed a contract with Flint in the Class D Southern Michigan League. There the 19-year-old Duncan began flashing the strong bat that would be the trademark skill of his career. Appearing in 97 games with 385 at-bats, Duncan hit .299 with 156 total bases and a .405 slugging average. His performance impressed league rivals in Battle Creek, and in October of 1913 they purchased his contract from Flint. In 1914 Duncan played in 147 games, hit .285 with 43 extra-base hits, and was signed for 1915. Beset by unusually harsh weather at the beginning of the season, all the league’s teams suffered financially, and after the first half of the season ended, the league folded, freeing all the players to find work elsewhere in the game.

Pat Duncan’s search for employment ended quickly; he was offered a contract by the Pittsburgh Pirates. He joined the team in Philadelphia on July 8. The Pirates were looking for help in center field to supplement the left-handed hitting Zip Collins. After sitting out a week recovering from a sprained ankle suffered the week before, he was inserted into the lineup by manager Fred Clarke on the 16th. Playing center field against the Boston Braves in Boston, Duncan was hitless in three at-bats before being removed for a pinch-hitter. He pinch-hit the following afternoon in Brooklyn but came up empty. Two days later Duncan pinch-hit again against Brooklyn’s Nap Rucker and got his first major-league hit, a single. The at-bat was also Duncan’s last appearance as a Pirate. A week later the team optioned him to Grand Rapids of the Central League. At the end of August an article in Sporting Life mentioned Duncan’s “fine pace” at Grand Rapids.

The 1916 season was Duncan’s finest to date as a professional. In 124 games he batted.328 with a slugging percentage of .430. He got himself into some trouble during a game when he punched an umpire during an argument. (No record of any punishment could be found.) His batting performance caught the eye of Birmingham in the Class A Southern Association, and the Barons purchased his contract from the Pirates. With the World War looming, Duncan, like many others, played sporadically in the 1917 and 1918 seasons. In 1917 he only appeared in only 35 games, and in 1918 he played in 67 games before the league shut down on June 18. A month later on July 21, Duncan enlisted in the Army. His duty kept him stateside. He was discharged in May 1919 and headed to Birmingham to reclaim his position and resume his quest to return to the major leagues.

In August 1919, hitting the ball hard and batting.323, Duncan was purchased by the first-place Cincinnati Reds, who were thin in the outfield because of Sherry Magee’s illness and converted pitcher Rube Bressler’s hitting woes. Duncan’s return to the big leagues was slow to start: He pinch-hit three times in his first ten days with the team, then made his first start in a game against the Philadelphia Phillies on August 26. From then on he was more or less a regular and helped the Reds capture the National League pennant for the first time. He played in left field for all eight of the World Series games against the Chicago White Sox (soon to be called the Black Sox), went 7-for-26 and led the Reds with 8 RBI. In the field he played errorless ball.

In 1920 Duncan was the only Red to appear in all the team’s games, hitting .295 and finishing second on the squad with 88 RBIs. Playing in a park not known for surrendering the long ball, he helped provide the next best thing: triples. His 11 three-baggers made him one of four Reds with double-digit triples. But the Reds were unable to defend their title, finishing in third place, 10½ games back of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

For the next three seasons Duncan patrolled the wide expanse of left field at Redland Field. In 1921, the park was in its tenth season and no one had yet hit a ball over the fence without the benefit of a bounce. The first ball to clear the fence on the fly was hit in late May by John Beckwith of the Chicago Giants of the Negro National League. Then on June 2, with the last-place Reds playing the St. Louis Cardinals, Duncan dug in against left-handed hurler Ferdie Schupp with a runner on second and one out. Duncan connected. The ball rocketed toward left field, easily cleared the wall, and Duncan had registered Organized Baseball’s first home run to go out of the park in Redland Field. It cleared the 12-foot concrete wall by four to six feet, and it traveled an estimated 400 feet.

Duncan finished the season with an average of .308 on 164 hits. The next season was even better; he hit a career-high .328 with 94 RBIs. Much of this success was on the strength of 12 triples, 8 home runs and 44 doubles; the latter figure has been topped seven times in Reds team history. Despite his efforts Duncan and the Reds were again unable to get back to the World Series, finishing in second place seven games behind the New York Giants.

Duncan got off to a slow start in 1923. As the Reds battled for first place with the Giants and Pirates, his power numbers were lower than expected. But as soon as the weather warmed up, so did Duncan. He was on a tear as the Reds arrived in New York to face the first-place Giants in a five-game series beginning on August 15. The Giants had recently taken five straight from the Reds at Redland Field and the Reds needed a good showing to get back in the race. The opening day was a doubleheader and both the Reds and Duncan came out blazing. The Reds took both games, and Pat achieved the second four-hit game of his career in the opener. In the second game he got two more knocks and at the end of the day he was 6-for-9 with 5 RBIs. Three days later the excited Reds left town with four wins under their belts. The euphoria was short-lived; it was shattered by an article in a Chicago-based “sporting” magazine called Collyer’s Eye. The article said Duncan and teammate Sammy Bohne had been offered $15,000 each to throw some games against the Giants in the series at Redland Field earlier in the month. National League President John Heydler questioned both players. Duncan, who had compiled seven hits in the series, and Bohne both swore under oath that they had had no dealings as described in the weekly.

Heydler said he believed both men and suggested that they, and the Reds, sue the magazine. The two players and the team decided that the Reds would sue Collyer’s. The case lingered in the courts for four years before being settled with a $100 payment to the Reds. The story was finally put to rest when Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis vindicated both players following the settlement.

Duncan finished 1923 strong (.327, 83 RBIs), but 1924 proved to be a greater challenge to him. An early-season ankle injury suffered in a slide plagued him all season, limited him to 96 games. At the end of the year Duncan had his lowest hitting numbers since his debut in 1919 (.270, 37 RBIs). After the season there was much talk in the papers about the Reds remaking their outfield; all scenarios were discussed, including rumors that Duncan would be moved to another team, maybe even the minor leagues. Facing a possible demotion, Duncan threatened to quit the game and tend to his growing cigar-manufacturing business. The threat turned out to be a bluff. The Reds eventually dealt his rights to the Washington Senators, who flipped his contract to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. The 31-year-old Duncan never returned to the big leagues.

From 1925 to 1927 Duncan was the starting left fielder for the Millers, batting .345, .341, and .352. He topped 200 hits twice. But after batting .343 in 60 games for the Millers in 1928, he was dealt to Rochester of the International League. In 43 games he hit.252 for the Red Wings, and found himself looking for work after the season. In 1929 he signed with Chattanooga of the Southern Association to try to get back on track, After 40 at-bats in Chattanooga he was let go. Duncan tried one last time to catch on with the Millers but was cut loose there as well.

At the age of 35, Duncan returned to his birthplace in the hills of Ohio. He resided in Jackson County and worked for the state highway department as a building superintendent. He regularly appeared in Cincinnati during his retirement years, participating in annual old timer’s contests and league celebrations like the National League’s 60th birthday in 1936. He participated in a three-inning old timer contest in 1951 celebrating the league’s 75th birthday. On July 17, 1960, Louis Baird “Pat” Duncan died of complications related to cancer. His baseball legacy was attached to his home run that cleared the left-field wall of Redland Field in 1921.

Sources

Lee Allen, Cincinnati Reds (NewYork: Putnam, 1948)

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001)

Greg Rhodes, Crosley Field (Holt, Michigan: Partners Publishing Group, 1995)

Greg Rhodes and John Snyder, Redleg Journal (Eagan, Minnesota: Road West Publishing, 2000)

Cincinnati Enquirer, June 3, 1921

Cincinnati Commercial, June 3, 1921

Cincinnati Times-Star, June 3, 1921.

New York Times, July 19, 1960

Sporting Life, July 31, 1915

The Sporting News, October 9, 1924

The Sporting News, May 22, 1924

The Sporting News, November 27, 1924

The Sporting News, March 1, 1928

The Sporting News, August 20, 1931

The Sporting News, September 10, 1931

The Sporting News, June 4, 1936

The Sporting News, July 16, 1936

The Sporting News, February 14, 1951

The Sporting News, July 27, 1960

Baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet.com

Lee Sinins Baseball Encyclopedia

Ohio.gov

Hall of Fame player file for Pat Duncan

Additional research provided by Sandy Derenbecker

Full Name

Louis Baird Duncan

Born

October 6, 1893 at Coalton, OH (USA)

Died

July 17, 1960 at Jackson, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.