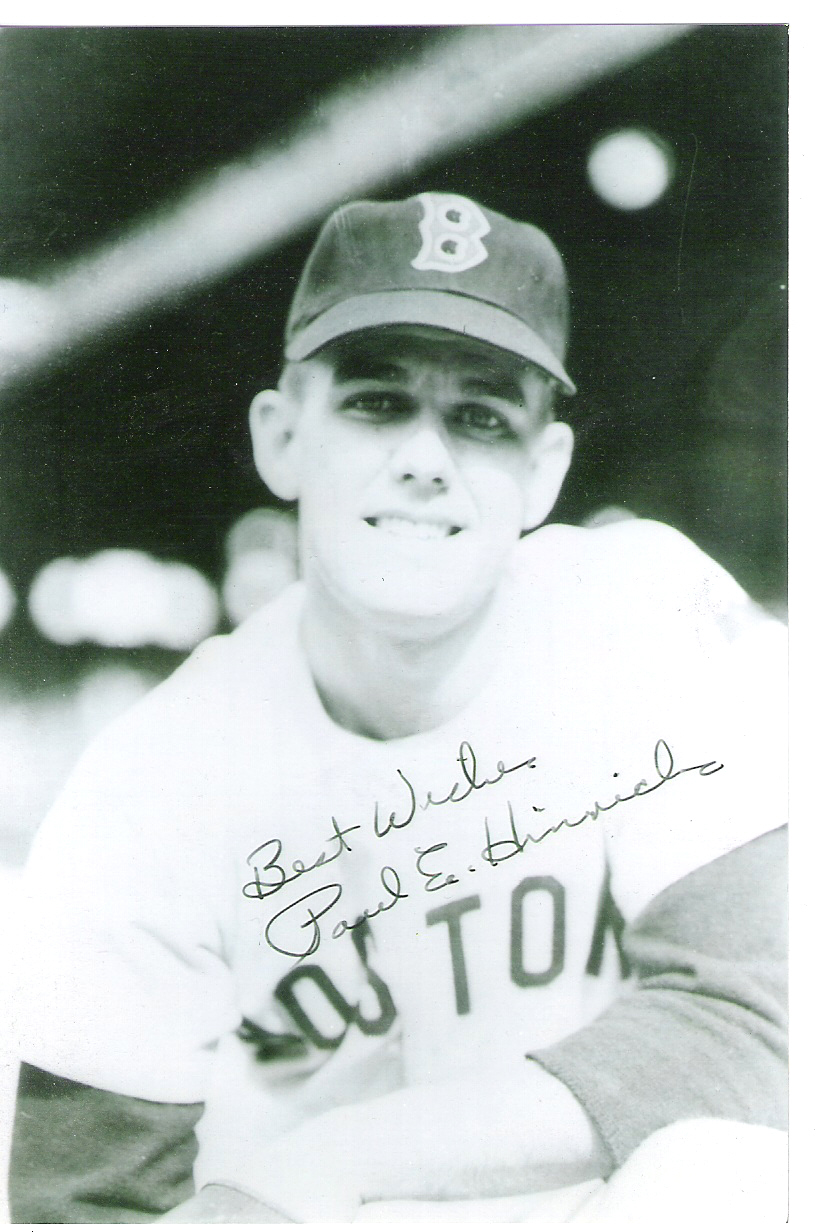

Paul Hinrichs

It was about a bad a brief outing as a pitcher could have, but at least it was mercifully short. Fortunately, there are other things in life that might have greater meaning than a bad outing on the mound.

It was about a bad a brief outing as a pitcher could have, but at least it was mercifully short. Fortunately, there are other things in life that might have greater meaning than a bad outing on the mound.

It was at Comiskey Park, and the Boston Red Sox were already down, 6-2, after 7½ innings in the second game of a June 3, 1951, doubleheader against the White Sox. Boston had won the first game, 5-3, behind the pitching of Mel Parnell and Ellis Kinder, largely thanks to the four runs batted in by Vern Stephens on a double and a single, each hit driving in two.

Red Sox manager Steve O’Neill had already pulled his starter, Chuck Stobbs, after four runs in four innings, and replaced reliever Bill Evans, who’d given up two more runs in the one-plus inning he worked, Walt Masterson threw two scoreless innings but was lifted for pinch-hitter Fred Hatfield, who doubled to lead off the top of the eighth and then scored on Dom DiMaggio’s single. That was it for the top of the eighth, though, and Paul Hinrichs was brought in to pitch the bottom of the inning, facing the 3-4-5 batters in the White Sox lineup.

Hinrichs was a right-hander, listed at an even 6 feet tall and 180 pounds.

It was the second appearance in a big-league game for Hinrichs. The right-hander’s debut had been a little more than three weeks earlier, on May 16, also against the White Sox, but that time at Fenway Park. That game had also been a Stobbs start, but Stobbs had gotten only one out – the first batter he faced, Chico Carrasquel, had grounded back to him on the mound. There followed a single, a walk, another single to load the bases, and then a double, a single, and a Nellie Fox triple. Five runs in already and just one out; Steve O’Neill called in Hinrichs to relieve. An attempt to score Fox from third on a bunt to first base failed when the bunt was hit too hard and Fox had to hold. White Sox pitcher Joe Dobson flied out to center to end the inning.

After getting the first out in the second, Hinrichs allowed a base on balls and then a single, another single, a sacrifice fly scoring a seventh run, and then a triple by Jim Busby drove in the eighth White Sox run. O’Neill had seen enough and he pulled Hinrichs. At least there had only been 5,828 fans at Fenway, though his manager and coaches had seen him struggle.

Getting his second shot to pitch, this time in front of more than 35,000, Hinrichs took over with a fresh inning ahead of him – no pressure of inherited baserunners, and in a 6-2 game that was still winnable but not that close.

Minnie Minoso was the first batter and he singled to left field. With Eddie Robinson at bat, Minoso stole second on Hinrichs and Red Sox catcher Les Moss. Robinson then doubled to left field, scoring Minoso. Hinrichs walked Bud Stewart. Jim Busby was up and Hinrichs threw two pitches that were far from the strike zone. Not wanting to see any more, O’Neill pulled Paul Hinrichs in mid-batter and brought in Mickey McDermott, who walked Busby to load the bases. The walk was charged to Hinrichs. Next up was Carrasquel, and he tripled to clear the bases. All five runs were charged to Hinrichs, and it was 11-2 in favor of the White Sox.

Hinrich’s ERA had jumped from 20.25 to 47.25, but things got better a little later. It was again 2½ weeks before he was used once more. On June 20 the Cleveland Indians were at Fenway Park. O’Neill had already gone through five Red Sox pitchers, and the score was 13-6 in Cleveland’s favor. Hinrichs was asked to get through the top of the ninth. The first batter he faced was Bobby Avila. He hit an inside-the-park home run high off the center-field wall and flagpole, which then bounded into right-center. It was Avila’s third home run of the game, eclipsing the total of two major-league home runs he had hit in his 157 prior big-league games.

But then Hinrichs struck out Larry Doby and got the next two batters to fly out. One inning, one run. The very next day, he got the ball again. This time, it was after seven innings, with the Indians ahead, 8-4. Hinrichs pitched the top of the eighth inning. There was a walk and a single, but he got three outs, all of them secured by Red Sox infielders. It was one full inning of work, without a run. His ERA was now 21.60 – and that is where it remains today. Hinrichs never worked again in the major leagues, other than an inning in a June 25 exhibition game against the New York Giants at Fenway Park.

In fact, his time in baseball was pretty much done. Another calling awaited him.

Paul Edwin Hinrichs was born in Marengo, Iowa, on August 31, 1925. His father, Rev. Carl F. Hinrichs, was pastor of the Trinity Lutheran Church at Mallard, Iowa. Rev. Hinrichs was born to German immigrant parents. His wife, Martha, was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1891. As of the 1930 census, when the family was living in May City, Iowa, the couple had eight children, four girls and four boys. Rev. Hinrichs had also been a good pitcher in his college days at Concordia. Older brother Marvin became a minister. Sister Martha was an all-state basketball player in Iowa.

After eight years of school, Hinrichs attended Concordia College (a Lutheran prep school) for six years, in St. Paul, Minnesota. While there, he earned his way into ballgames the way a number of kids did at the time. “Where did I learn to pitch? Watching American Assn. games in St. Paul. … I waited for baseballs to be batted out of the park, and gained admission by turning them in.”1 But he hadn’t played baseball there, at least at first. He was turned down both his freshman and sophomore years as “too small and too light.” He played right field some in 1941, and pitched some when the team’s main two pitchers suffered sore arms. In 1942 some of his teammates were a day late to return from Easter vacation and were suspended. Though he had been on time himself, he decided to “stand by my teammates, so I, too, was barred from the team.”

And he missed 1943, too, “too busy with my studies” in his first year at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis. He played some – outfield, and then pitching – in 1944. In 1945, a pitcher for good now, he was 9-1, against a number of top college teams. The war in Europe was over, and the war in the Pacific was just winding down. “The first year I was down there [St. Louis],” he remembered, “they didn’t have a team because of the war and then one of the guys from the school, a catcher, was trying to get a team together. He asked me to pitch and I said OK. We beat Missouri U. and Washington University and St. Louis University. We had a good team.”2

It was in 1946, playing ball on the seminary team and pitching a no-hitter against Washington University of St. Louis, that Hinrichs was discovered by baseball scouts.3 Hinrichs was signed by the Detroit Tigers as an amateur free agent. SABR’s Scouts Committee reports that it was Bruce Connatser who signed Hinrichs for the Tigers out of Concordia on June 10.

Hinrichs worked at both his studies and baseball, taking one semester of college a year, from September to January. At one point, he took a couple of courses at Washington University to make up for a couple he’d had to miss. After his career was complete, his told his congregation that he’d played baseball in order to support himself through college and seminary.4 Hinrichs observed at the time, “Entering the ministry at 32 or 33 is not unusual.”5 He could follow baseball as far as he could, and then pursue his calling.

Hinrichs was assigned to play in 1946 in Lubbock, Texas, in the West Texas-New Mexico League. It was Class-C baseball and the 20-year-old righty (he turned 21 in August) had a 10-6 season with a 2.76 ERA in 19 games. There was a rumor, he said, that he wouldn’t pitch on Sundays, but “it was without basis.” He told Dan Daniel, “I am not opposed to pitching on Sundays. A man can get to church before noon.”6 He added, acknowledging that he was known for not swearing, “Whatever habits the other players have, particularly in the form of language they use, I consider their business. I joined the game. It didn’t join me. I’m in baseball to do the best I can. Like all young players my goal is the majors.”7 Dallas Morning News columnist George White dubbed him “Dallas’ pitching parson.” He was not a “reformist working for converts among his constituents.” Indeed, “Paul never made a show of himself. He never imposed his ideas on others.”8

In 1947 Hinrichs trained with the Double-A Dallas Rebels in spring training and made the team. He won one and he lost one, but spent most of the season with the Lubbock Hubbers, where he was 18-5. He struck out 213. Lubbock won the pennant, 14 games ahead of second-place Amarillo. The Hubbers swept the first round of the playoffs, then beat Amarillo in the finals, four games to two.

After a hard line drive off his arm in 1948 spring training, Hinrichs missed a couple of months in the spring and into the season, but when he got going, he started with a string of wins. Then he suffered some close defeats and the Dallas team lost a lot of games, finishing 28 games out of first place. Hinrichs’ record was 9-10, with a 3.60 ERA. He was still in the Tigers’ system, but not for long. There were “suspected irregularities in player traffic involving the Detroit and Dallas clubs.”9 Commissioner Happy Chandler oversaw an investigation and determined that 10 players with Dallas, including Hinrichs, had been “covered up” in contravention of baseball policy, essentially players who had been held for Detroit in excess of the number of players they were permitted to keep in their farm system. The commissioner declared all 10 free agents.10 The decision was dated October 27, 1948, and a copy is available in Hinrich’s Hall of Fame player file.

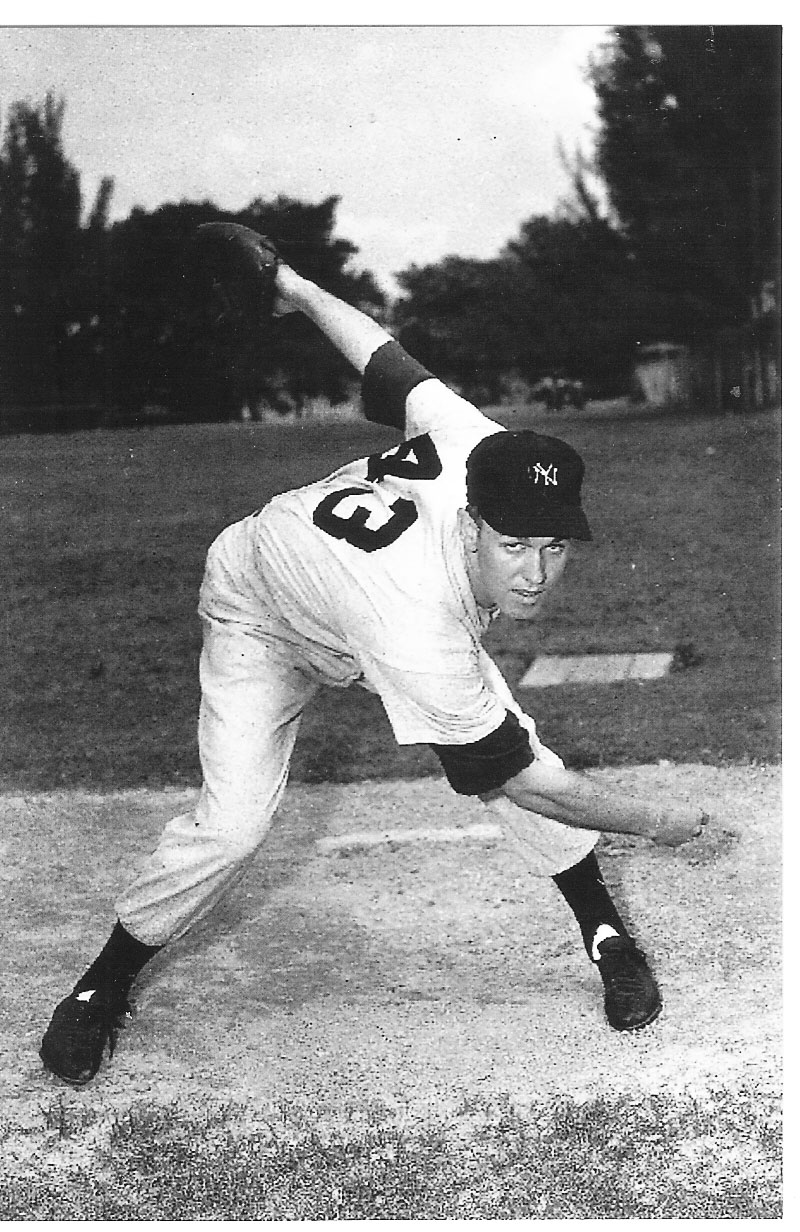

No longer bound to the Tigers by the reserve clause, Hinrichs had leverage. He said he would ask his father to help him come to a decision. Hinrichs had 12 or 13 offers, perhaps ranging as high as $75,000, from among the 16 major-league clubs, and he signed with the New York Yankees on November 15. He was said to be the first bonus player signed by the Yankees.11 (Later reports of the bonus amount ranged from $20,000 to $75,000. In 2015 Hinrichs himself said, “It was above 50.”) In 1948 he said, “It was a lucky break, the kind a ballplayer dreams about.”12 Whatever the amount, it was later reported that he donated “a sizable part of the bonus he received” to two Lutheran churches.13 “The White Sox offered me a good contract, too, but I went with the Yankees because they told me they’d take me to spring training with the Yankees and give me a chance to make the team.” Scouts Tom Greenwade and Lou Maguolo reportedly closed the deal at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis just before midnight on the 15th.14 The Yankees assigned him to the Triple-A Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He did train in the spring with the New York team.

No longer bound to the Tigers by the reserve clause, Hinrichs had leverage. He said he would ask his father to help him come to a decision. Hinrichs had 12 or 13 offers, perhaps ranging as high as $75,000, from among the 16 major-league clubs, and he signed with the New York Yankees on November 15. He was said to be the first bonus player signed by the Yankees.11 (Later reports of the bonus amount ranged from $20,000 to $75,000. In 2015 Hinrichs himself said, “It was above 50.”) In 1948 he said, “It was a lucky break, the kind a ballplayer dreams about.”12 Whatever the amount, it was later reported that he donated “a sizable part of the bonus he received” to two Lutheran churches.13 “The White Sox offered me a good contract, too, but I went with the Yankees because they told me they’d take me to spring training with the Yankees and give me a chance to make the team.” Scouts Tom Greenwade and Lou Maguolo reportedly closed the deal at the Chase Hotel in St. Louis just before midnight on the 15th.14 The Yankees assigned him to the Triple-A Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He did train in the spring with the New York team.

The spring started off well. “Counting the intrasquad games, I had 24 innings of shutout ball in spring training, but then I got hurt. They went to play someplace else and left me home. We went out to run and it had rained the night before. I slipped in the mud and I tore my leg. [It was a groin injury.] Then I found out I had a defective leg I was born with. One of the doctors thought I might have had a touch of polio when I was little. And I couldn’t get it to heal. Back in those days, they just kept you pitching. I kept pitching and I kept getting a sore leg. Then they made a reliever out of me.”

Hinrichs hadn’t sufficiently impressed the Yankees. “Casey Stengel was the manager when I was with the Yankees. He didn’t know I was on the elevator and somebody asked about me, and he said, ‘Aw, he’ll never make it. He’s too much of a Christian.’ You gotta be mean to play ball.” News reports at the time said that Stengel felt he needed more seasoning.

The groin injury during the season hampered his work with Kansas City. He was 3-10 in 26 games, with a 4.79 ERA; the team was 71-80. And in 1950, when the Blues finished in last place (54-99), Hinrichs was 6-5 (with 49 appearances, all but four in relief) with a 5.53 ERA. The Yankees chose not to protect him and he was left exposed in the Rule 5 draft, and selected by the Red Sox on November 16, 1950.

He’d impressed Red Sox observers in 1949. “When I was at Kansas City and we were playing Louisville, I accidentally knocked Jimmy Piersall down. And while he was in the dirt, he looked up at my catcher and he said, “Is Hinrichs mad at me?” The catcher had the presence of mind to say, “You better believe it.” The rest of the year, whenever he came up with men on bases, I knocked him down and I beat Louisville four times that summer. Boston drafted me the next year. ….

“I had planned to quit the year before and then I heard on the radio that I had been sold by the Yankees to the Red Sox. Back in those days, they didn’t tell you. They didn’t ask you. You found out about it in the newspaper or on the radio. I told my wife, ‘I guess I’ll play for another year.’”

The Boston Herald said that “the lack of a good relief pitcher” was the “main problem of the past three years.”15 Hinrichs’ father died in late March and he left the team briefly, but returned and had his time in the big leagues. He’d never had an at-bat. He had a 1.000 fielding percentage, having made one play – an assist.

Hinrichs was with the Red Sox for more than six weeks after his last appearance. On August 5, 1951, he was sent to Kansas City. The next day, Kansas City sent him to the San Francisco Seals on option. He appeared in five games for the Seals, and was 0-3 (4.88).

Now it truly was time to quit. “I didn’t have a good year with the Red Sox. I didn’t think I was going to make it big. I had graduated so I was ready to take the call. I called the seminary and told them I was ready.” On September 14, 1952, Hinrichs was ordained in the ministry at Our Redeemer Lutheran church in Augusta, Georgia. He was assigned to build a congregation and a church in Aiken, South Carolina.

Normally, a seminary student would spend one year out of school for vicarage, but an accommodation was made due to Hinrichs’ time in baseball. “I had never vicared in those days, because I was playing ball, so they sent me to start a mission in South Carolina where DuPont was building the H-bomb plant after the war. I built a church there and we built a parsonage and then we expanded the church. That was five years and then I got a call to do the same thing in Southern California. Los Angeles – La Puente. That was really growing. We grew to 500 members and had 500 kids in Sunday school in five years. That was unbelievable.

“Then I got a call back to St. Louis, which I didn’t want to take, but they flew me in to interview me and I realized that the area they wanted to put the church was out in the country and it was going to grow the next 30 years so I decided to take that call. That church really grew, too. We got up to 1,400 members; there were about 35 when I got there. I stayed there for 22 years, and then I took a pre-retirement call to a smaller congregation. When you’ve got a big congregation, you’re sitting in meetings all the time and you finally end up not being a pastor to people. You’re an administrator with other people working under you. I didn’t like that part so I took a call to a small congregation in Litchfield, Illinois. I retired when I was 63.”

Paul had met his wife, Frances Dora Rauscher, when both were singing in the church choir in St. Louis. They married on December 16, 1948. Their first son, Mark, was born late in 1950. Four other children followed – three daughters and then another son.

Hinrichs’ brief time in baseball helped him in his work for the church. “It opened all kind of doors for me when they found out I had played professional baseball. It still does today.” As a Red Sox alumnus, even though he’d only pitched briefly, Hinrichs was brought to Boston in 2012 for the special ceremony to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park. “They flew me up for that 100th anniversary. I got to meet all the guys. They gave us a book and I went around and have everybody sign it. That was a wonderful thing that they did.”

Last revised: April 14, 2015

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Hinrichs’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Paul Hinrichs for agreeing to be interviewed and then for reading the final result to check for any errors.

Notes

1 Dan Daniel, “Hurling Parson,” undated 1949 column in unidentified newspaper, found in Hinrichs’ Baseball Hall of Fame player file.

2 Author interview with Paul Hinrichs, January 27, 2015. All quotations attributed to Hinrichs are from this interview unless otherwise indicated.

3 Journal Star (Peoria, Illinois), September 14, 1952. The seminary had produced three other major leaguers – Bill Wambsganss, Max Carey, and Dick Seibert. See the New York Times, November 17, 1948. Concordia president Lewis Sieck explained that there was a good reason why so many athletes could come from a relatively small institution: “Our students study long and hard; the studies are academic and involved. By the time they have finished their ministerial training [11 years], they’ve learned that one of the finest methods of relaxation and physical and mental rejuvenation is to participate in some form of athletics. As a result more than 85 percent of our young men participate in our intramural and intercollegiate athletic program which includes virtually all the major and minor sports.” See “Pitchers and Parsons,” Rawlings Mfg. Co. Roundup, May 1949, 6, 7.

4 Augusta Chronicle, October 21, 1952.

5 The Sporting News, April 13, 1949.

6 Dan Daniel, “Hurling Parson” op cit.

7 Dallas Morning News, March 11, 1948.

8 Ibid.

9 Dallas Morning News, September 2, 1948.

10 Dallas Morning News, October 28, 1948.

11 New York Times, November 17, 1948.

12 Bob Broeg, The Sporting News, November 24, 1948. Bizarrely, there was another pitcher named Hinrichs, also from Iowa, also in the Tigers system, and also declared a free agent by the commissioner. Gene Hinrichs (no relation) pitched five seasons in the minors but never advanced above Class B. See The Sporting News, April 13, 1949.

13 Boston Globe, March 25, 1949. The Mount Calvary Lutheran church in St. Louis and the Trinity Lutheran Church of Mallard were the reported recipients.

14 Bob Broeg, The Sporting News, November 24, 1948.

15 Boston Herald, November 19, 1950.

Full Name

Paul Edwin Hinrichs

Born

August 31, 1925 at Marengo, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.