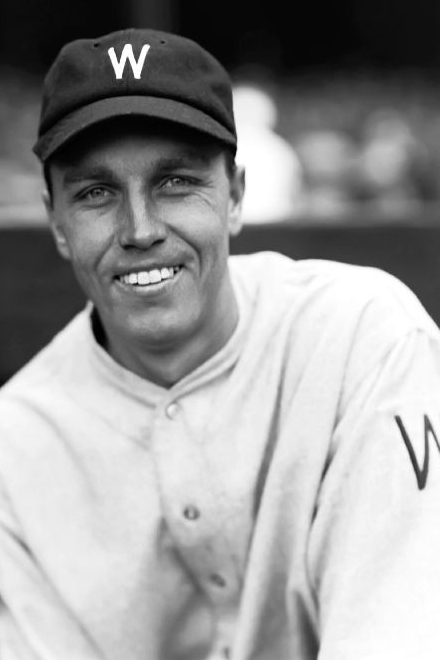

Paul Hopkins

Babe Ruth was not the first batter Paul Hopkins faced in his major league debut on September 29, 1927, at Yankee Stadium. Pitching for the Washington Senators, Hopkins did serve up Ruth’s 59th home run, which tied a record Ruth set in 1921. Ruth’s second blast of the game was a grand slam on a three-two count and it would solidify Hopkins’ place in baseball history.

Babe Ruth was not the first batter Paul Hopkins faced in his major league debut on September 29, 1927, at Yankee Stadium. Pitching for the Washington Senators, Hopkins did serve up Ruth’s 59th home run, which tied a record Ruth set in 1921. Ruth’s second blast of the game was a grand slam on a three-two count and it would solidify Hopkins’ place in baseball history.

Hopkins, who joined Washington 10 days before from New Haven (Eastern League), started the fifth inning with the Senators behind 11-4. Ruth was the fifth batter he faced, the blast coming with one out.

Born in Chester, Connecticut, in 1904, “Hoppy,” the son of a local baseball legend, was always a hero in his hometown and neighboring Deep River, where he spent most of his life. It was the Ruth homer, however, that earned Hopkins late-in-life recognition

Catcher Pat Collins, batting eighth, was the first to face Hopkins and he promptly singled. Pitcher Dutch Ruether reached on an infield error. Collins was cut down at the plate trying to score on an Earl Combs single but Mark Koenig continued the hit parade, loading the bases for Ruth.

It was catcher Bernie Tate’s suggestion to “throw Ruth nothing but curveballs.”

Talking with Sports Illustrated’s William Nack (August 24, 1998), Hopkins couldn’t recall how many pitches he threw to Ruth. He did remember “nibbling outside and in” with curveballs and Ruth hitting two “monstrous fouls.” “I thought I’d never get him out of there,” Hopkins told Nack. “I threw him nothing but curves.

“A beautiful curve,” Nack quoted Hopkins. “… slow and over the outside of the plate. It was so slow Ruth started to swing and then hesitated, hitched on it and brought the bat back. And then he swung, breaking his wrists as he came through it. What a great eye he had! He hit it at the right second. Put everything behind it. I can still hear the crack of the bat. I can still see the swing.”

“Then the fifty-ninth!” John Drebinger reported the next day in the New York Times. “That, countrymen, was a wallop. …The ball landed halfway up the right field bleacher and though there were scarcely 7,500 eyewitnesses present, the roar they sent up could hardly have been drowned out had the spacious stands been packed to capacity. The crowd fairly rent the air with shrieks and whistles as the bulky monarch jogged majestically around the bases, doffed his cap, and shook hands with Lou Gehrig who was waiting his turn at bat.”

Hopkins struck out Lou Gehrig. He got help from Red Barnes again, the right fielder cutting down Bob Musuel at the plate for the third out, the latter trying for an inside-the-park home run. “When the inning ended I got to the dugout, I suddenly felt very upset and tears began to roll down my face,” he recalled for Jack Cavanaugh in the September 24, 1995, New York Times.

Hopkins finished the game, pitching out of jams in the sixth and eighth. In the seventh Ruth came very close to homering again. “On his final turn at bat [Ruth] sent Barnes with his back to the wire screening in front of the same bleacher to pull down a soaring fly. A foot or two more of distance and a new record would already be established,” wrote Drebinger. Hopkins then got Gehrig on a groundout to end the inning.

“Hopkins had a big league baptism which must have made him mourn for dear old New Haven,” the Washington Evening Star suggested. His final line: four runs, three of them earned; eight hits; one strikeout; one walk.

“Not in all his spectacular years had the Babe had a greater day than this,” wrote the New York Sun’s Frank Graham, declaring it Babe’s Greatest Feat in Baseball.” There were “… lots of happy people. Hopkins was not one of them.”

Following the series with the Yankees the Senators returned to Washington to play out the season against the Philadelphia Athletics. He talked himself into getting the start.

Working the first five innings in a 9-5 win, Hopkins allowed five hits, fanned four and walked three four before giving way to Ralph Judd, another rookie.

In just two games, Hopkins had faced six future Hall of Famers – the Yankees’ Gehrig, Ruth and Tony Lazzeri, the Athletics’ Jimmy Foxx, Mickey Cochrane and Al Simmons.

Following his senior season at Colgate in 1927 Hopkins reported to George Weiss’ New Haven Profs. While he wasn’t happy with it, he had no choice. At the end of his sizzling sophomore season (1925) at Colgate (he was 10-2), he had signed a $4,000 deal with Weiss calling him to report to New Haven following his graduation.

“It was not legal but not unique either,” Hopkins pointed out. “It was enough money for half my junior year and all my senior year.”

Hopkins had been a standout at tiny Chester High (graduating in 1921) and at Dean Academy in Franklin, Massachusetts (winning 11 of 12 starts over two years). Over those summers, he played with the Chester and East Hampton town teams in the Middlesex County League, one of Connecticut’s premier semipro circuits.

He picked Colgate over Dartmouth because of Coach Bill Reed and catcher John Barnes, the latter going on to a long minor league career.

He was 6-0 as a freshman. An 11-inning, 6-3 win at Yale, a 3-2 decision at Princeton and a 10-strikeout, five-hit, 4-3 win at Fordham, were all part of his sophomore campaign. Against Wesleyan in Middletown, Connecticut, he hit “the longest home run in Andrus Field history” according to the Middletown Press.

Weiss had to be waiting anxiously because Hopkins continued to impress, both at Colgate and with the Ivoryton team in Middletown County League. Backed by a factory, Ivoryton was well funded, it played on one of the best fields in the state and drew crowds that sometimes reached 4,000.

The July 11, 1925, Middletown Press reported, Hopkins, after throwing for team President Wilbert Robinson and manager Zack Wheat, “was offered a job with the Brooklyn team if he would terminate his college course, but it is believed he will turn the offer down since he has only one more year at Colgate. He has everything that a promising youth pitcher should have, coolness, control and speed and the build to stand a strenuous season.”

Jack Coffy, the Fordham coach and a Cincinnati scout, the story added “has passed judgment on [Hopkins] and found him not wanting as a big league possibility.”

It is testimony to Hopkins’ belief that he was at the top of his game in 1925-26.

Hopkins shared the County League spotlight over the 1925-26 seasons with “Young Ed” Walsh, the son of the Hall of Famer. Attending Notre Dame, Walsh pitched for the Middletown team and locked horns with Hopkins twice.

“Hoppy” beat Walsh in 1925 but it was a 17-inning, 4-4 tie on Aug. 4, 1926, that is now legend in South Central Connecticut. Hopkins, who went into the game with a 6-1 record, allowed seven hits, walked four and fanned 15, including the last hitter of the game. Walsh, who went in with a streak of 27 scoreless innings, fanned 18 including two of the final three hitters he faced.

After pitching Ivoryton to the pennant, Hopkins returned to Colgate. In one of his finest college efforts, he pitched a five-hit, 10-strikeout, 12-2 win over Michigan in Ann Arbor. The next day he homered over the center-field wall. He recalled the Tigers offering him $10,000 to sign but Weiss spurned all Hopkins’ efforts to make a deal.

The 1927 New Haven team was actually the worst Weiss had in the Elm City and Hopkins’ pro debut was not easy. He won only three of 10 decisions. One of those wins was especially big – a 3-0 shutout of the Providence Grays on Aug. 14. Senators’ pitching great Walter Johnson was watching.

It was, however, as a relief pitcher that Hopkins was making his mark. Following his sale to Washington (for a reported $10,000) on Labor Day weekend, Senators scout Joe Engle told The Sporting News “Hopkins is the best looking mound prospect he has seen this season and it is claimed he has been the most effective hurler in the Eastern League.”

Hopkins went 7 2/3 innings to beat Pittsfield on Sept. 15 then added three scoreless innings of relief on back-to-back days against Waterbury and Pittsfield, the latter in the season finale on Sept. 18. He then headed for Washington and his spot in baseball lore.

He reported to spring training in Tampa in late February 1928 and came north with the Senators, now managed by Walter Johnson. In early May he joined Montreal (International League) managed by George Stallings, who he called “the best manager I ever had.” Used primarily in relief, he was 7-9 for the Royals but finished strong with two route-going efforts – 5-4 over Jersey City on Aug. 27 and 11-4 over Toronto on September 3. Washington recalled him on September 12 but he saw no action.

Breaking camp with the Senators in 1929, Hopkins was used exclusively in relief. His only major league loss came on May 23 against the Athletics. He entered the game in the fourth, putting an end to an eight-run A’s rally that tied the score. In the top of the fifth, he gave up a solo home run to Bing Miller that proved to be the difference in the game.

He was claimed by the St. Louis Browns on waivers on June 26 and after only two appearances – a total six scoreless innings – he was shipped to Wichita Falls of the Texas League. It did not go well in the Texas heat – 20 hits allowed, 10 walks and a loss over 11 innings in nine games. On December 5, 1929, the Browns released Hopkins to Milwaukee.

He could recall vividly the pitch that pretty much ended his career – a fastball at the Browns’ spring training facility in Ft. Pierce, Florida, in March 1930. He said nothing, threw in pain and came north with Milwaukee but after only 12 games, he was finished.

He did seek medical help (an operation actually made it worse) and he got looks from Montreal, and from Allentown and New Haven of the Eastern League, but he was finished as a player but not as a baseball personality.

He ran a restaurant back home in Chester for a while, spent some time in the insurance industry and, after moving to Deep River, went to work for Boston-based Shawmut Bank in 1938, retiring in 1968. Hopkins never stopped being a local hero. During World War II, he was on the town rationing board and actually played some on the town team. After the war he got to watch his son Peter follow him to Colgate after an impressive high school career. Peter, a catcher, was part of Colgate’s 1955 College World Series team.

Hopkins served a term as president of the semipro league that helped establish him, a circuit Peter played in as well. A grandson, also Peter, carried on with high school, college (Eckert) and semipro credentials. A member of the Madison Country Club, Paul Hopkins shot his age with such frequency that people stopped paying attention.

And he signed autographs, a dozen a week or so. Then he was invited to the Babe Ruth Birthplace Foundation’s unveiling of statue of the Bambino in Baltimore in May 1995. He was the last surviving pitcher that Ruth homered off in 1927.

In the ensuing years he threw out the first pitch at Yankee Stadium, Fenway Park and in Baltimore; entertained the media at the presentation of an ESPN documentary in New York in August 1998; was a hit at Cooperstown; and, perhaps the highlight, appeared with David Letterman on the “Late Show.” He was written up everywhere including Sports Illustrated and the New York Times. He was busy locally as well, celebrating his 99th birthday in September 2003 by speaking to daughter-in-law Sherry Hopkins’ sixth-grade class in Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

Some five months after becoming the oldest major leaguer, Hopkins passed away in Middlesex Hospital on January 2, 2004. He rests beside wife Jean in Deep River’s Fountain Hill Cemetery. Every fall, there is a tour of the place and the guide points out Hopkins’ grave. He is still a local hero.

Author’s note

Like Hopkins, Pete Zanardi is a Chester, Connecticut, native and like most of that ilk, listened to Hopkins’ stories since his youth. Hopkins was an established family friend.

Sources

Books

Fleming, G.H. Murderers’ Row: The 1927 New York Yankees. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985.

Mosedale, John. The Greatest of All: The 1927 Yankees. New York: Dial Press, 1974.

Articles

Ahlquist, Eric. “A Ruthian debut still drawing attention.” Cooperstown Crier, Oct. 10, 1991.

Barton, Bob. “Pitcher takes stroll down memory lane.” New Haven Register, Jan. 6, 2000.

Caruso, Mike. “The man who gave up Babe’s 59th.” Hartford Times, April 4, 1976.

Caruso, Mike. “Hopkins’ feats remembered.” Hartford Times, April 5, 1976.

Cavanaugh, Jack. “A 3-2 pitch that was No. 59.” New York Times, Sept. 24, 1995.

Drebinger, John. “Ruth Hits 2, Equals 1921 Homer Record … .” New York Times, Sept. 30, 1927.

Francis, Bill. “Hopkins spent collegiate years at Colgate.” Cooperstown Crier, Oct. 2, 1984.

Goldburg, Jeff. “Try the Curve Kid A Rookie Pitcher from Connecticut Did and the Rest is History.” Hartford Courant, Aug. 16, 1998.

Keane, Albert W. “Calling ‘Em Right.” Hartford Courant, Sept. 2, 1927.

Kelley, Brent. “A daunting debut, facing Babe Ruth.” Sports Collectors Digest, Sept. 29, 1995.

Nack, William. “Colossus.” Sports Illustrated, Aug. 24, 1998.

Serby, Steve. “He’ a Living Footnote to Legend of Bambino.” New York Post, July 15, 1998.

Standard, Charles. “Hopkins Dies, Faced Ruth.” Hartford Courant, Jan. 3, 2004.

Van Nes, Claudia. “A Past Full of Baseball, the Babe.” Hartford Courant, Sept. 26, 2003.

Vigoda, Ralph. “Yielding Ruth’s 59th homer makes pitcher unforgettable.” Philadelphia Inquirer, Sept. 28, 1997.

Zanardi, Peter. “He got two hits off Grove, pitched to Babe.” The Pictorial, Oct. 2, 1984.

Zanardi, Peter. “Three-and-two equaled 59 Chester man’s debut was a grand moment for Babe.” Herald (New Britain, CT) Press, Sept. 14, 2003.

Zanardi, Peter. “Remembering a local hero … .” Pictorial Gazette (Old Saybrook, Connecticut), Jan. 13, 2004.

Articles, no author

“Chester Wins Bates Cup.” The New Era (Deep River, Connecticut), June 17, 1921.

“Paul Hopkins Pitches To Brooklyn Hitters.” The Middletown (Connecticut) Press, July 11, 1925.

“Family Boasts Two Pitchers, Father and Son … .,” Hartford Courant, July 18, 1926.

“Middletown and Ivoryton play 18 inning tie – Paul Hopkins and Young Ed Walsh Hook up in Mound Battle.” Hartford Courant, Aug. 2, 1926.

“Paul Hopkins Gains Mound Prestige by Colgate Activities.” Hartford Courant, May 20, 1927.

“Good showing for Chester Boy … .” The New Era, Aug. 5, 1927.

“Hopkins Leads Profs to Fourth Straight Over Providence.” Hartford Courant, Aug. 14, 1927.

“Paul Hopkins of Profs obtained by Washington Club.” Hartford Courant, Sept. 1, 1927.

“Griff average up to Previous Year.” The Sporting News, Oct. 13, 1927.

“Jersey City Bows to Montreal … Hopkins Firm in Pinches.” Aug. 28, 1928.

“Montreal takes two … .” New York Times, Sept. 4, 1928.

Diamond Anniversary of The New Era. The New Era, Nov. 3, 1949.

Sporting News, Sept. 8, 1927.

Full Name

Paul Henry Hopkins

Born

September 25, 1904 at Chester, CT (USA)

Died

January 2, 2004 at Middletown, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.