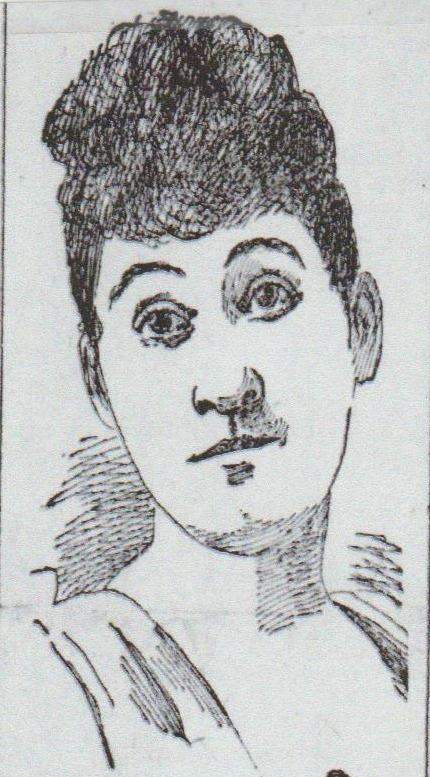

Pete McNabb

In the early evening of February 28, 1894, former Baltimore Orioles pitcher Pete McNabb and his paramour, actress wannabe Louise Kellogg, retired to the room that they shared in a Pittsburgh hotel. Moments later, three gunshots rang out from inside. Then, a fourth. Those responding to the scene found McNabb lying on the floor, dead from a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. Still alive but mortally wounded, Kellogg was removed to a nearby hospital, where she lingered for another 32 hours before her demise completed the murder-suicide. The ensuing paragraphs profile the perpetrator of this grim deed.

In the early evening of February 28, 1894, former Baltimore Orioles pitcher Pete McNabb and his paramour, actress wannabe Louise Kellogg, retired to the room that they shared in a Pittsburgh hotel. Moments later, three gunshots rang out from inside. Then, a fourth. Those responding to the scene found McNabb lying on the floor, dead from a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. Still alive but mortally wounded, Kellogg was removed to a nearby hospital, where she lingered for another 32 hours before her demise completed the murder-suicide. The ensuing paragraphs profile the perpetrator of this grim deed.

Biographical data on McNabb published in present-day baseball reference works are riddled with errors, including misidentification of his birth name, birthplace, and nickname.1 Close examination of the historical record establishes that our subject was born Edward Jacob McNabb on October 24, 1865,2 in Bedford, Ohio, a rural township located in the east-central region of the state.3 He was the seventh of nine children4 born to farmer John B. McNabb (1824-1904) and his wife Susannah (née Adams, 1829-1895).

The McNabb clan descended from Scottish Methodists who had emigrated to Virginia prior to the Revolutionary War. Our subject’s immediate forbears had resided in Bedford since grandfather John McNabb (1785-1851) cleared the family farm in the early 1800s. Nothing is known of the early life of Pete (as he was known in baseball) McNabb until he left home as a teenager to work as a train dispatcher for the Santa Fe Railroad.5 By the late 1880s, he was employed as a telegrapher in Winfield, Kansas.6

In April 1888, McNabb (who batted and threw right-handed) made a belated debut in professional baseball as a catcher-right fielder for the Leavenworth (Kansas) Soldiers of the four-club Western League.7 By the time the circuit disbanded in late June, he was playing the same positions for a WL replacement club situated in Newton, Kansas.8 Thereafter, McNabb played in the unaffiliated New Mexico League (where he may have taken up pitching).9

McNabb began the 1889 season pitching full-time for the Waco Braves of the low-minor Texas League. Despite working for a last-place club, he was the class of circuit hurlers, going 20-10 (.667) and leading the league in strikeouts (261) and ERA (1.53).10 A local Sporting Life correspondent was duly impressed, declaring, “McNabb of Waco is a pitcher who would hold his own in the National League or American Association. He is the speediest twirler in the league, fields his position splendidly, and has fine command of the ball.”11

In early July, McNabb’s release was purchased for $1,000 by the Denver Grizzlies of the faster Western Association.12 There, he promptly transitioned from being one league’s best pitcher to another league’s worst, posting a wretched 3-18 (.143) record for Denver. Notwithstanding that dismal mark, the club brought him back for the 1890 season, and was rewarded when McNabb got off to a sterling (19-7) start. But the $50 fine imposed on him and teammate George Treadway in early August for breaking curfew and dissipation13 coincided with a marked drop-off in McNabb’s performance. Still, pitching for a Grizzlies club that otherwise went 29-43 (.403), he finished with a commendable 28-21 (.571) record, a 2.16 ERA, and 206 strikeouts.14 During that season, McNabb also shed some light on his views about the situation. “I play to win always, but I make some bad plays at critical times which I can’t help. The Denver team plays as good ball as any of the association teams, but is out of luck and that goes a long way toward winning.”15

McNabb returned to Denver for a third season in 1891 but did not enjoy the success of the previous campaign. Plagued by control problems, he went 3-10 (.231) in 22 appearances before being released in mid-August. McNabb quickly hooked on with another Western Association club, the Omaha Lambs, but fared no better (1-7, .125) in nine outings before being released again.

Pete McNabb finished the 1891 season in Portland, where two life-changing events occurred. Toiling for the Portland Webfoots of the four-club Pacific Northwestern League, he regained pitching form, going 6-0 with a 1.15 ERA in seven appearances. And he met one of the club’s most ardent fans, Mrs. W.E. Rockwell, née Lulu Louise Lewis (or Louis), the wife of an ex-minor leaguer active in Pacific Northwest baseball circles.16 At the time, the Rockwells were estranged, most likely over Louise’s desire to launch a career on the stage. In any event, Mrs. Rockwell and Pete McNabb soon commenced the illicit love affair that would end with their deaths.

McNabb returned to Portland in 1892, but only after contentious offseason haggling about his salary. “Peter McNabb, who couldn’t pitch quoits in the Western Association last year, only wanted $375 a month from Portland for next summer, but didn’t get it,” reported The Sporting News, caustically.17 Whatever his ultimate salary, McNabb turned in solid work for the Webfoots. His record stood at 16-16 (.500) with a 2.12 ERA in over 250 innings when the Pacific Northwestern League folded in mid-August. Pete then signed with the Los Angeles Angels of the independent minor California League.18 Joining him there was his mistress, reportedly working as a “skirt dancer” at local nightclubs under her maiden name Lulu Lewis.19

Pitching late into the calendar year, McNabb went 21-10, with a scintillating 0.98 ERA in 286 innings pitched for Los Angeles, leading California League hurlers in winning percentage (.677).20 By season’s end, he was extolled as “the star of the Pacific Coast pitchers.”21 Understandably, McNabb’s achievements – a combined 37-26 (.587) record22 and a yeoman 544 2/3 innings pitched – stimulated interest by major league clubs. And the following February, the 27-year-old was signed by the Baltimore Orioles of the National League.23 His paramour, engaged as a chorus girl by the Alvin Joslyn theatrical troupe, came East with him, adopting the stage name Louise Kellogg.24

Coming off a last-place finish in 1892, Baltimore club president-manager Ned Hanlon was slowly assembling the players who would soon transform the Orioles into the champions of the 12-club National League. Joining future Hall of Famers John McGraw, Joe Kelley, and Wilbert Robinson for the 1893 campaign was some new blood for the infield.25 But Hanlon’s principal off-season objective had been finding arms to help staff ace Sadie McMahon. And coming off his previous year’s performance, Pete McNabb seemed a likely prospect. Good-sized – he was “about six feet tall, strongly built … and weighed, when in condition, 185 pounds”26 – McNabb also seemed possessed of a rubber arm. But McNabb was dogged by ill health throughout his tenure with the Orioles. In spring camp, he suffered from physical weakness and other problems then believed to stem from a bout of malaria, but which were more likely the early symptoms of tuberculosis.27

Whatever the underlying cause of his condition, McNabb remained idle during the first two weeks of the regular season. He made his major league debut on May 12 against the Washington Senators, pitching a strong first six innings before running out of gas. Still, a four-run ninth-inning Orioles rally allowed McNabb to claim a 7-6 victory. He also made “a good impression” on the Baltimore press.28 Pete reinforced that impression by winning his next three starts, and then turning in a sterling seven-inning, two-hit relief stint in a 15-4 win over Brooklyn.29 Thereafter, however, his work became inconsistent, with victories being surpassed by defeats.

During this time, our subject’s health became a serious concern, with Sporting Life observing that “pitcher McNabb of Baltimore has been a sick man all season and has won his games through headwork. Despite his weakness he has not pitched a bad game this year and by his earnest and brainy work has become a prime favorite.”30 But after Pete was hit hard in a 14-5 loss to St. Louis on June 28, manager Hanlon pulled him from the Baltimore rotation. A month would pass before he received another starting assignment. In the meantime, McNabb, “still a sick man and instead of getting stronger seems to be getting weaker,” was sent home to rest.31

Upon his return, McNabb “pitched great ball”32 but dropped a 6-5 verdict to Boston. A week later, he was hit hard in a no-decision start against New York. After the game, concern about the state of McNabb’s health resurfaced, with a wire service dispatch observing: “It is a pity that McNabb … has been in ill health all this season. If he had been himself he would have been one of the most effective men in the league.”33 On August 11, Pete threw two ineffective innings (five hits, three runs allowed) in relief of Sadie McMahon to close out an 11-7 loss to the Beaneaters. Baltimore released him immediately thereafter,34 with newspaper announcement of the dismissal coupled with regret that it was occasioned by McNabb’s poor health.35

Facing the high-octane offenses ushered in by the pitching rule changes of 1893,36 McNabb had hurled effectively, posting an 8-7 (.533) record for a Baltimore team that otherwise went 31-43 (.419) during his time with the Orioles. He posted a club-best 4.12 ERA, and his 1.549 WHIP was second only to that of staff ace McMahon (1.542). But like other pitchers that season, McNabb allowed a liberal number of base hits (167 in 142 innings pitched) and his ratio of 18 strikeouts to 53 walks was poor. Still, it was indisputable that ill health, rather than inadequate performance, had prompted McNabb’s release.37

In an effort to regain his wellbeing, McNabb returned to the warmer climes of California for the rest of the summer. That fall, he attempted to resume pitching, signing with a local all-star nine that also included Washington Senators right-hander Lester German.38 But his appearances were often canceled by illness.39 Nevertheless, there was still interest in McNabb’s services for the 1894 season, and his signing by the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Rippers of the high-minor Western League was considered something of a coup for the club. “McNabb is regarded as the best pitcher reserved by the Western League,” opined Sporting Life.40

Prior to reporting for spring training, McNabb rendezvoused with Louise Kellogg in Pittsburgh. On February 27, 1894, the couple registered at the upscale Eiffel Hotel as “E.J. McNabb and wife.”41 While there, they encountered and socialized with Pete’s former Denver Grizzlies teammate Lou Gilliland. Early the following evening, McNabb and Louise retired to their room, where they quarreled. Louise later informed authorities that McNabb became upset when she informed him that she intended to remain in the Pittsburgh area to care for her elderly parents. He, in turn, accused her of having a romantic interest in Gilliland.

Prior to reporting for spring training, McNabb rendezvoused with Louise Kellogg in Pittsburgh. On February 27, 1894, the couple registered at the upscale Eiffel Hotel as “E.J. McNabb and wife.”41 While there, they encountered and socialized with Pete’s former Denver Grizzlies teammate Lou Gilliland. Early the following evening, McNabb and Louise retired to their room, where they quarreled. Louise later informed authorities that McNabb became upset when she informed him that she intended to remain in the Pittsburgh area to care for her elderly parents. He, in turn, accused her of having a romantic interest in Gilliland.

Moments later came the initial series of three gunshots from inside the room, followed by the fourth. Gilliland, who had been outside in the hallway, responded to Louise’s cry for help and forced open the door. Inside lay the dead body of Pete McNabb, crumpled on the floor. He had shot himself through the mouth with a revolver.42 Although gravely wounded, Louise was still alive and conscious, telling Gilliland that McNabb had shot her. “Lou, he has killed me,” she reportedly said upon Gilliland’s entry into the room.43 Louise was thereafter transported to a nearby hospital, but her injuries were beyond medical assistance. One of the three McNabb gunshots had inflicted spinal cord damage that left her partially paralyzed. Surgery to remove the bullet lodged near her spine was deemed infeasible, making the patient’s death only a matter of time.

Louise was able to provide a brief account of the incident to investigators before lapsing into a coma. She died early on the morning of March 2. By that time, McNabb’s body had already been released to his family and transported to Mt. Vernon, Ohio, where the remains were quietly buried in Mound View Cemetery. A coroner’s inquest dutifully adjudicated the deaths as a murder-suicide,44 but its underlying cause remained uncertain. A packet of letters between McNabb and “your loving wife”45 revealed that Louise had been sending money to McNabb throughout the winter.46 But it was unclear whether she had threatened to cut him off. More likely, McNabb was suspicious that Louise had taken a fancy to Gilliland and had shot her in a jealous rage.47 Or ill and near destitute, McNabb may have attempted to kill them both out of despair.48 But without a suicide note or dying declaration by the killings’ perpetrator, this is all speculation. In the end, McNabb’s motives are unknowable. Nevertheless, baseball’s semi-official post-mortem was unsparing in its judgment on the deceased, deploring his crime and pronouncing that “his reputation was that of a crank, or one who was inclined to emotional fits, which rendered him unfit for the duties of his position.”49

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the McNabb file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the McNabb entry in Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2, David Nemec, ed. ((Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census data and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Bill Lamb.

Notes

1 Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and other modern authority identify our subject as Edgar J. McNabb; his birthplace as Coshocton, Ohio, and his nickname as Texas, all of which are wrong. Efforts to correct these and other reference work errata regarding McNabb were ongoing at the time that this bio was submitted.

2 This birthdate appears premised entirely upon a single source, a November 1890 wire service profile of McNabb. See “Denver’s Expert Twirler,” Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune, November 9, 1891: 9, and Cheyenne (Wyoming) Leader, November 2, 1891: 4. The 1870 US Census has McNabb born “about 1863,” while a home county Ohio newspaper placed his birth on an undetermined date in 1862-1863. See “A Terrible Tragedy,” (Coshockton, Pennsylvania) Democratic Standard, March 9, 1894: 1.

3 The Bedford Township where McNabb was born is located in Coshockton County, and not to be confused with the City of Bedford, a Cleveland suburb.

4 The other McNabb children were Theretas (born 1851), Joseph (1852), Laura (1856), William (1858), Dora Rachel (1859), Florida May (1861), George (1867), and James (1870).

5 Per the McNabb entry in Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol. 2, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 401. See also, “Baseball Notes,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Globe, March 5, 1894: 6.

6 As reported in “Movement of Base Ballists,” Newton (Kansas) Evening Kansan, July 30, 1888: 4; “Base Ball Notes,” Newton (Kansas) Republican, July 27, 1888: 4.

7 See “First Game of Ball,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Times, April 24, 1888: 1.

8 Per “Movement of Base Ballists” and “Base Ball Notes,” above.

9 See “Base Ball Tips,” Santa Fe New Mexican, April 12, 1889: 1.

10 Per The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3d ed., 2007), 154.

11 “Galveston Glints,” Sporting Life, June 12, 1889: 5.

12 As reported in “Denver Secures Pitcher McNabb,” St. Louis Republic, July 3, 1889: 6, and “Bought by Denver,” Fort Worth Gazette, July 2, 1889: 2.

13 The McNabb and Treadway fines were subsequently reported in “Sporting Notes,” (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, August 18, 1890: 2, and “Hardly Believe It,” Denver News, August 12, 1890: 7.

14 McNabb’s won-loss record was calculated by the writer from newspaper box and line scores. The other stats were published in the Omaha World-Herald, October 19, 1890: 9, and St. Paul Globe, October 19, 1890: 7. Baseball-Reference provides no data for McNabb’s time with the 1890 Denver Grizzlies.

15 “How to Play Ball,” Denver News, August 29, 1890: 7.

16 More on the Rockwells is provided online by Brian McKenna in a Baseball Fever post dated May 19, 2008.

17 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1892: 3. The barb originally appeared in the Omaha Bee, January 24, 1892: 17. Earlier, McNabb’s salary demands had been pegged at $350/month. See “Minor Mention,” Sporting Life, January 16, 1892: 11.

18 As reported in “The National Pastime,” Los Angeles Herald, August 25, 1892: 2.

19 See “Wages of Sin,” (Stockton, California) Evening Mail, March 2, 1894: 3. See also, McNabb, Major League Player Profiles, 402.

20 Per The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, which inexplicably confers the California League ERA crown upon George Harper of the San Jose Drakes (1.21), rather than McNabb.

21 According to “Sporting News,” Baltimore Sun, February 4, 1893: 6.

22 The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball gives McNabb a 23-11 record but lists his league-leading winning percentage as .677, congruent with the 21-10 record that Baseball-Reference accords him with Los Angeles in 1892.

23 See “Sporting Notes,” Denver News, February 16, 1893: 3; “Three More Men Captured for Baltimore,” Sporting Life, February 11, 1893: 3.

24 McNabb’s paramour is not to be mistaken for Clara Louise Kellogg (1842-1916), a once-renowned opera singer.

25 In early June, Baltimore added another future Hall of Famer to the roster, acquiring shortstop Hughie Jennings via a trade with the Louisville Colonels.

26 Per “Suicide of Pitcher McNabb,” Baltimore Sun, March 1, 1894: 2. Modern-day baseball reference works list McNabb as slightly smaller.

27 See McNabb, Major League Player Profiles, 402.

28 See “The Field of Sport,” Baltimore Sun, May 13, 1893: 7.

29 As reflected in published newspaper game accounts/box scores and the Retrosheet games log for the 1893 Baltimore Orioles.

30 “Editorial Views, News, and Comment,” Sporting Life, June 17, 1893: 2.

31 “Baltimore in Pittsburg,” Baltimore Sun, July 3, 1893: 6.

32 “Two More Defeats,” Baltimore Sun, July 29, 1893: 6.

33 See e.g., “Diamond Gossip,” Nebraska State Journal, August 6, 1893: 15.

34 As reported in “General Sporting Notes,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1893: 12; “McNabb’s Health Is Poor,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Herald, August 12, 1893: 6; and elsewhere.

35 Same as above. See also, “Outside the Diamond,” Chicago Inter Ocean, August 14, 1893: 3.

36 The elimination of the pitcher’s box and the elongation of the pitching distance to the present-day 60 feet, six inches, fueled a surge in National League batting in 1893.

37 Commenting upon McNabb’s release, a Sporting Life correspondent stated that “his pitching while he was in the league, although almost all the time troubled by sickness, has been above that of any youngster who entered the National League this season.” See “At a Distance,” Sporting Life, September 16, 1893: 10.

38 Per “All Californians,” Sporting Life, October 21, 1893: 2.

39 See e.g., “A Game in Sacramento,” Sporting Life, December 30, 1893: 3: “Pete McNabb had been billed to pitch but he did not feel well enough to handle the ball and Joe Cantillon was substituted.”

40 “An Inter-Club Row,” Sporting Life, January 27, 1894: 1. McNabb signed with Grand Rapids for $175/month, plus $200 advance money.

41 The instant account of the McNabb-Kellogg murder-suicide has been drawn from various newspaper sources. The most complete coverage of the incident was published in the Pittsburgh press. See e.g., “Locked In and Murdered,” and “Hotel Tragedy,” Pittsburgh Post, March 2, 1894: 1-2; “Wound Fatal” and “M’Nabb Jealous,” Pittsburg Press, March 1-2, 1894; “Louise Will Die,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, March 2, 1894: 2.

42 An autopsy subsequently determined that a bullet had passed through the roof of McNabb’s mouth and entered the brain, killing him instantly.

43 Per “Pitcher McNabb’s Suicide,” Baltimore Sun, March 2, 1894: 6.

44 Per “M’Nabb’s Victim Dead,” Pittsburgh Post, March 3, 1894: 2.

45 While conscious, Louise denied that she and McNabb had been married the previous New Year’s Eve. Her husband (W.E. Rockwell) was Catholic and would not consent to their divorce, she said. It was also revealed that Louise was the mother of a six-year-old son (Thomas) who resided with his father. See “Hotel Tragedy,” Pittsburgh Post, March 1, 1894: 1-2.

46 As subsequently reported in a wire service story published in small-town midwestern newspapers. See e.g., “A Complete Tragedy,” North Platte (Nebraska) Telegraph, March 10, 1894: 2; “Murder and Suicide,” Santa Fe (Kansas) Monitor, March 8, 1894: 1.

47 See “M’Nabb Jealous,” Pittsburg Press, March 1, 1894: 1.

48 See “M’Nabb’s Crime,” Sporting Life, March 3, 1894: 1.

49 “A Tragedy in the Profession,” 1894 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 66.

Full Name

Edward Jacob McNabb

Born

October 24, 1865 at Bedford, OH (USA)

Died

February 28, 1894 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.