Phil Todt

In early 1925, the New York Yankees offered to trade Lou Gehrig to the Boston Red Sox for first baseman Phil Todt to repay Boston for the blockbuster Babe Ruth trade a few years earlier. The Red Sox turned the Yankees down. So says the official Gehrig site (www.lougehrig.com). But was it true? Both debuted in the minor leagues in 1921, but Gehrig had a .344 minor-league average through 1924 and Todt’s was .309. Todt had proved himself at the major-league level, though, with one year’s experience under his belt (.262 in 103 at-bats), while Gehrig’s short stints in 1923 and 1924 didn’t provide enough of a sample size. Gehrig had taken off all of 1922 by going to Columbia. And the Yanks already had rock-solid Wally Pipp at first base. The story seems to be correct; Todt’s obituary in The Sporting News says that New York had offered Gehrig straight up to Boston owner Bob Quinn, but Quinn demurred. [The Sporting News, December 1, 1973]

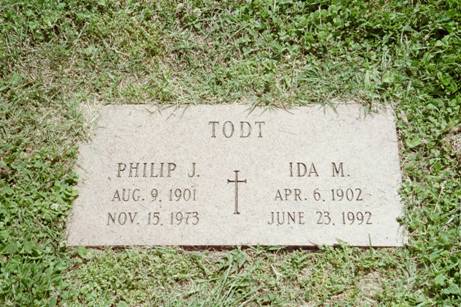

Philip Joseph Todt was a left-handed first baseman/outfielder from Missouri, born in St. Louis on August 9, 1901. His mother, Cecilia (Julius) Todt, was Missouri-born, but his father, Anton, hailed from the Westphalia region of Germany, arriving in the United States in 1880. He was a cemetery worker who by 1910 had become superintendent of the cemetery. The family lived on the St. Peter and Paul’s Cemetery grounds, and Philip was born at home, thus quite accurately born in a graveyard. The German word “tot” translates to English as “dead.” [Washington Post, April 1, 1921]

Phil was the second-born of five children, the others being Kasper, Marie, Dorothy, and Julius. Kasper became a real-estate clerk, and Phil was working as a bank clerk in 1920 as he awaited his break in baseball. The youngest, Julius, became a cemetery laborer by 1930.

Phil was born near the hotel where the big-league players stayed in St. Louis. That’s how he got hooked on baseball, and he got to know some of the people around the game. He started pitching at Kendrick High School and was already attracting attention at the age of 15. After Kendrick he went to boarding school in Clayton, Missouri, at Chaminade College Preparatory School, and lettered in football and basketball, as well as baseball. He also pitched in the St. Louis Municipal League, for the Arcadias, who won the pennant. There he was spotted by Branch Rickey of the Cardinals, who attempted to sign the 16-year-old to a Cards contract. That fell through when Phil’s father refused to co-sign the agreement, because Phil would have had to quit high school. Phil himself said it truly was while he was in prep school that he decided to become a ballplayer. He had “no desire to enter college for an engineering degree. It was natural for me to ask the Browns to sign me as a pitcher and perfectly natural for them to tell me I was a better outfielder. So I wandered away to Tulsa where I played the outfield and first base.” [Appleton Post Crescent, March 11, 1931]

Browns scout Pat Monahan signed Phil for the Browns. Monahan later boasted, “I’m the only scout in history who ever dug up a player in a graveyard.” He said he literally brought Browns general manager Bob Quinn to the cemetery to meet Todt. [The Sporting News, March 16, 1968. See also an unidentified July 21, 1926, article by veteran Boston sportswriter John Drohan found in Todt’s Hall of Fame player file.]

Nineteen-year-old Phil reported to the Browns for spring training in 1921, and manager Lee Fohl earmarked him for Tulsa in the Class A Western League. He figured in the very first decision handed down by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Because Phil was 16 years when he signed the contract with the Cardinals, they claimed they had prior rights. Since Anton Todt had refused to co-sign for his minor child, however, it was not a valid agreement and it was a simple enough decision: Phil was free to sign with the Browns. [Washington Post, February 23, 1921] He impressed. A March 15, 1921, article in the Chicago Tribune said he was “lanky and strong” and had “poled about as many drives over the right field fence as has George Sisler” but added, “He needs experience.”

Todt got a lot of it in Oklahoma, amassing a large 611 at-bats with the Tulsa Oilers, and batted .306, hitting 28 home runs for the last-place club. Still deemed to need more seasoning, he was farmed out in 1922 to the Columbus Senators in the Double-A American Association, another last-place team, where he hit .273 in 267 at-bats, his season cut short by a shoulder injury.

The Browns’ option on Todt ran out by 1923 and he was sold to the San Antonio Bears of the Texas League, where manager Bob Coleman made a first baseman out of him. He played in 125 games and hit .333. He was deemed ready for the big leagues. After three years managing the Browns, Lee Fohl had taken the reins of the Boston Red Sox and Boston bought his contract and that of four other Bears on September 10. The Red Sox themselves were perennial last-place teams in these years. Taking first place in his heart was a young lady named Ida Marie Reinhardt and the two married in 1924. They later had two children, Phyllis and Charles.

The Red Sox held spring training that year in San Antonio, so in one sense Phil just kept on. He made the team in a backup role and didn’t start his first game until June 12. He’d pinch-hit and filled in, his first big-league hit coming in his sixth game, a two-run single hitting for pitcher Oscar Fuhr. He backed up first baseman Joe Harris. Harris had a tonsillectomy in mid-June, giving Todt more of a chance to play than might otherwise have been the case. On June 22, he hit a single, a double, and his first major-league home run, scoring three of the runs in Boston’s 6-2 win over the Yankees. Phil appeared in 52 games, hitting the aforementioned .262 that seems to have piqued the interest of the Yankees.

Over the wintertime, Fohl said he planned to start Todt at first base, despite Harris hitting .301 in 1924. At the end of April 1925, Harris was traded to Washington and the job was Todt’s to keep. He filled the Red Sox first-base slot for the next six seasons. In 1925 he played in 141 games, increased his batting average to .278, and hit 11 home runs, driving in a career-high 75 runs. He led the Red Sox in both of the latter two categories. Some of the hits were real drives; his May 6 home run was the first one hit over the heightened right-field wall in Washington.

Todt homered twice against the Yankees on April 23, 1926, his second one winning the game in the 10th. He played in 154 games, but he fell off slightly in most offensive categories, and even in fielding, committing a career-high 22 errors. The 1,881 chances he handled at first base set a new major-league record. All in all, Todt was an excellent first baseman with a lifetime fielding percentage of .992. His average declined in 1926 from .278 to .255 but his seven homers still led the Red Sox and his 69 RBIs were tops of the team, too. This may not say much for his teammates, but that’s the way it was. He hit one less homer in 1927, and still led the Red Sox. While Babe Ruth was hitting 60 for the Yankees, Todt’s six led the Babe’s former team. The Red Sox as a team hit only 28 four-baggers that season. Phil’s 52 RBIs ranked him third on the team. Bizarrely, Todt received one vote for MVP, but that was better than Babe Ruth did. The Sultan of Swat received none, because he had won the MVP award in 1923, and under the rules of the day was ineligible for further consideration. Lou Gehrig walked away with the honors.

Todt improved in 1928, his average climbing back to .252 and his homers climbing to a career high of 12, well ahead of the seven hit by the second-place finisher, second baseman Phil Regan. Todt’s 73 RBIs were two fewer than those of Regan, who led the team. Todt’s 21 sacrifice hits led the American League. His average climbed another 10 points, to .262, in 1930. For the five years through 1932, he was fairly consistent. In 1930, he faced competition from Bill Sweeney at first base. His average went higher still, but he appeared in only 111 games while Sweeney got into 88, hitting .309 in the process, though with less power and less production.

Sweeney was three years younger, and the Red Sox put both Todt and Johnny Heving on waivers. When presented with an offer from Philadelphia on February 3, 1931, the Red Sox decided to take the money for both of them at $7,500 apiece. Todt’s comment was that being released to the Athletics was “just the same as being kicked upstairs.” [Appleton Post Crescent, March 11, 1931]

The Red Sox’ Quinn was looking for more power. He didn’t get it. But he may have nonetheless made the right move in thinking Todt’s better days were behind him (Phil was 28). Todt ended up on a pennant-winner, but playing behind Jimmie Foxx he wasn’t going to get much playing time. He hit .244 but contributed 44 RBIs. His one moment in the 1931 World Series came in Game Seven, when he was put in to pinch-hit for starter George Earnshaw in the bottom of the eighth with the Cardinals up 4-0. He drew a base on balls, but was left stranded. St. Louis survived a ninth-inning rally to win the game, 4-2, and the Series. And on November 5, Todt was sent to the St. Paul Saints to complete a trade for first baseman Oscar Roettger.

Todt had a lot more baseball in him, and was the regular first baseman for the Saints for the next six seasons, 1932 through 1937. He played in almost every game every year, except in 1937 – but even then he played in 131 games. His average over the six-year stretch was .292 and he led all American Association first basemen in fielding for the six years, with a league record .998 in both 1934 and 1937. In 1933, he assumed the managerial reins for the last month of the season and when Gabby Street became ill in 1937, Todt took over as manager again. Babe Ganzel was named the new manager in November and on December 4, Todt and two others were traded to the Dallas Steers (Texas League). He played in 69 games in 1938 and was hitting.239 when he was traded to the Chattanooga Lookouts for Dale Alexander, the 1932 American League batting champion. Alexander said he wouldn’t play if he had to leave the Southern League. Todt played, got into six games, collecting five singles in 20 at-bats, and then seriously hurt his leg in a game at Knoxville. The traded called off, Alexander returned and started hitting. Todt was done for the year.

In 1939, Phil took up an offer to manage the Northern League’s Crookston Pirates in Minnesota. Crookston finished last, and Todt didn’t finish the season. He did put himself into three games and went 5-for-9 with two doubles, but those were his final at-bats in organized ball.

After he finished playing baseball, Todt ran a flower shop in St. Louis and was an official with the St. Louis Bowling Association. He played in a couple of old-timers games and helped run a baseball school in the early 1950s.

After he finished playing baseball, Todt ran a flower shop in St. Louis and was an official with the St. Louis Bowling Association. He played in a couple of old-timers games and helped run a baseball school in the early 1950s.

He died on November 15, 1973, and is buried in the same cemetery where he was born.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in this biography, the author consulted Todt’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Photo Credit

Fred Worth (gravesite)

Full Name

Philip Julius Todt

Born

August 9, 1901 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 15, 1973 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.