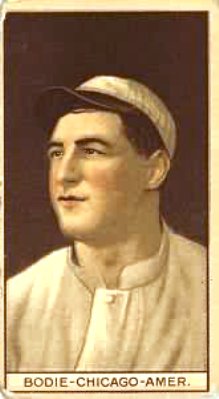

Ping Bodie

His name was Francesco Stephano (anglicized to Frank Stephen) Pezzolo, but baseball people called him Ping Bodie-Ping for the way the ball sounded when it came off his 52-ounce bat, Bodie for a town in California where he once lived. To confuse matters further, Ping’s brother Dave wrote to the editor of Sporting Life on February 17, 1912, that his brother’s name in Italian was Franceto Sanguenitta Pizzola. Dave added further that Ping took the name of Bodie from their uncle who was a ballplayer because he felt he would be ridiculed. Bodie, once a thriving Gold Rush and silver mining town with saloons everywhere and gunfights galore, is now a ghost town. The tumbleweeds blow silently and eerily through its dusty unpaved roads.

His name was Francesco Stephano (anglicized to Frank Stephen) Pezzolo, but baseball people called him Ping Bodie-Ping for the way the ball sounded when it came off his 52-ounce bat, Bodie for a town in California where he once lived. To confuse matters further, Ping’s brother Dave wrote to the editor of Sporting Life on February 17, 1912, that his brother’s name in Italian was Franceto Sanguenitta Pizzola. Dave added further that Ping took the name of Bodie from their uncle who was a ballplayer because he felt he would be ridiculed. Bodie, once a thriving Gold Rush and silver mining town with saloons everywhere and gunfights galore, is now a ghost town. The tumbleweeds blow silently and eerily through its dusty unpaved roads.

Ping Bodie was one of the first Italian ballplayers to make it to the majors. Ed Abbaticchio, probably the first major leaguer of Italian-American descent, and Bodie helped pave the way for the DiMaggio brothers and others like Frankie Crosetti, Tony Lazzeri and Phil Rizzuto.

Ever the optimist, Bodie had a great outlook on life and lived it to the fullest. He bragged a lot, but unlike most braggarts he was very popular with his teammates and the fans. There was a likeable quality in his make-up, a twinkle in his eyes, and an outgoing personality full of showmanship.

Ping liked to laugh it up and was usually the center of attention. He roomed with Babe Ruth when he was with the Yankees. When asked about what it was like to room with the Bambino, Bodie replied, “It was like rooming with a suitcase.” He would often say, “Did you see the way I smacked the old onion around?” Bodie is often credited (along with several other players, including Ed Walsh) with being the model of the ballplayer in Ring Lardner’s You Know Me Al stories that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, but he possessed a self-knowledge alien to Lardner’s Jack Keefe. Even Bodie’s failures brought a laugh. Bugs Baer, a sportswriter for the Hearst Publications, once described Ping’s attempt to steal a base: “There was larceny in his heart but his feet were honest.” Never modest, Ping asserted during a stint in Philadelphia under Connie Mack, “I and the Liberty Bell are the only attractions in Philadelphia.” Since he was playing on one of the worst teams ever, he was probably right.

Ping’s stunts occasionally involved animals. When the Yankees were in spring training in Macon, Georgia, several of the pitchers on the Yankee staff went to a carnival and with their great accuracy in knocking over bottles soon walked away with the top prizes-live ducks. Each pitcher had two ducks to carry. The next question was what to do with the ducks? Bob Shawkey had an idea. He phoned Ping Bodie and told him to take Izzy Kaplan, a photographer with the team, out to a movie. Ping, always eager to oblige with a practical joke, took Izzy out to the movie house. When Ping burst into laughter during a serious scene, Izzy in his middle European accent looked at Ping in puzzlement and said, “Vot’s da matter?” Ping replied, “I was thinking of something funny that happened back in San Francisco.” Ping burst into laughter again. This brought the manager down, who promptly threw them both out. When Izzy returned to his room and switched on the lights, he ran to the lobby yelling, “There’re ghosts in my room.” This got the attention of many people in the lobby.

The hotel manager and several Yankees went to the room to investigate. What they found were ducks swimming around in a full bathtub and several more flying around the room. Izzy demanded an explanation. Damon Runyon asked Izzy if he had left the window open, to which Izzy replied yes. Runyon said, “Maybe some wild ducks flew in.” Izzy, still fuming, replied, “And they also turned on the spigots, eh!”

On April 3, 1919, in Jacksonville, Florida, Ping went head to head with Percy the Ostrich in a pasta-eating contest. After the eleventh plate Percy could barely make it to the platter. Percy’s eyes were bloodshot and his sides were swollen. Percy appeared about to explode. Grown men and women departed from the spectacle. They felt sorry for the stuffed bird. Percy looked at the twelfth plate and swooned to his knees. Ping, sensing victory, grabbed his plate of spaghetti and downed it. The ostrich never recovered, and Ping was the winner. The official verdict was a technical knockout when Percy couldn’t answer the bell for the twelfth plate.

Sportswriter Wood Ballard described Ping Bodie’s physical appearance as anthropoid-like with broad stooping shoulders and long dangling arms which seemed to hang even lower when he trotted to and from his outfield position. One couldn’t miss him. Playing to the gallery, Ping made the most of these attributes and the fans loved it. Ping was very confident about his hitting and bragged he could “hemstitch the spheroid.” Nobody knew what he meant, but it sounded good. Ping even had his seven-year-old son sing his praises by parading through the stands and shouting, “My daddy can outhit any man in baseball.”

Born in San Francisco, on October 8, 1887, Ping was a first-generation Italian-American, a cocky kid from the Cow Hollow section of the city. His father, Joseph Pezzolo, was born in Italy and had been a miner in Bodie, California. His mother, Rose Marie Pezzolo (nee De Martini), was also born in Italy. W.O. (Bill) McGeehan, a famous sportswriter from San Francisco, said that Ping acquired his strength by rolling rocks down from Telegraph Hill. McGeehan put a tag on Ping, calling him a rock roller from Telegraph Hill. “They keep their territory free from invaders by digging rocks out of the summit and rolling them down the streets.”

Ping began his professional baseball career in 1905 in the California State League. He played all over the outfield and infield and even did a little pitching before finally settling down in the outfield, where he remained, with some trips to first base, for the remainder of his career. Joining the San Francisco Seals in 1908, he slugged 30 homers in 1910 and was called up by the Chicago White Sox in 1911. At first Bodie was on the bench. Charles Comiskey was unhappy about the lack of hitting on the team and said so publicly. Ping, taking advantage of this, went to Comiskey and said, “You want some hitting, put me in the lineup.” Comiskey told manager Hugh Duffy to do so, and Ping became a regular for four years with the Pale Hose hitting .289 (with 97 RBI), .294, .265 and .229. After his poor season and some clashes with manager Jimmy Callahan in 1915, he was sold back to the San Francisco Seals.

In 1917 Ping was back in the big leagues with the Philadelphia A’s, batting .291 in 148 games. The following year he was traded to the Yankees for first sacker George Burns. Ping was the first of the San Francisco Italians to join the Yankees. Tony Lazzeri, Frankie Crosetti, and Joe DiMaggio followed Ping to the Yankees. All had played on the sandlots of San Francisco. With the Yanks Bodie batted .256, .278 and .295 in three full seasons. He was with the Yanks until August 1921. After the Yanks went on to win the pennant that year, Ping asked for a half share of the World Series money, but he did not get it. Ping spent the next seven seasons in the minors playing with Vernon and San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League, Des Moines in the Western League and Wichita Falls and San Antonio in the Texas League. Ping’s major league career totals were a batting average of .275, 1011 hits, 43 homers, 516 runs batted in, and 393 runs scored in 1050 games. His minor league totals were considerably more impressive: .310 average, 1973 hits, 203 homers, 581 RBI (numbers are incomplete), and 990 runs in 1787 games

In 1925, Bodie divorced his first wife, Anna, whom he had married in 1908, claiming that she had circulated rumors that he was a bootlegger and a common drunk. But his principal complaint was that she was sending derogatory statements to Commissioner Landis and manager Huggins, attacking his character and conduct and calling him crazy. Ping and his wife had not lived together since 1923. They had two children, Frank and Frances Ann.

After his retirement from baseball Bodie was an electrician for 32 years on Hollywood movie lots and a bit actor, mostly with Universal Studios. Outgoing and popular, he made friends with many actors and actresses such as Charles Boyer and Carole Lombard. Ken Smith, a reporter with the New York Daily Mirror, went to do an article on Ping on a movie set. Upon entering the set, he saw Lon Chaney Jr. come out of the jungle through the foliage and transformed into a gorilla. The director yelled “Cut!” and suddenly there was Ping wearing a Yankee cap pulling a sound track wire into the foliage. Ping was as lively as ever as he performed his electrician duties. Ever the optimist, he was asked when he was 73 if he could still hit. He shot back, “Give me the mace and I’ll drive the pumpkin down Whitey Ford’s throat.” He would colorfully say to anyone who would listen, “Boy, how I used to whale the old apple and smack the old onion.” Ping also found time to oversee an automobile service station he owned near the Seals’ ballpark.

Pezzolo, Pizzola, Ping-he was a personality on and off the field. His lust for life and his quest to find the fun in it was genuine and made him many friends both in baseball and in Hollywood. There was no malice in his life. He had a smile for everyone, and if he liked someone, he would pull a harmless stunt on him.

Ping Bodie, age 74, died of lung cancer at Notre Dame Hospital in San Francisco on December 17, 1961. Ping was survived by his second wife, the former Edme Corken; his son and daughter; stepson Harry E. Corken; stepdaughter Dorothy H. Corken; two sisters, a brother, and three grandchildren. He was living at 2120 Larkin street in San Francisco at the time of his death.

Sources

Baseball Library.com.

Cataneo, David. Peanuts and Crackerjack. Nashville, Tennessee: Rutledge Press, 1991.

Hoie, Bob, and Carlos Bauer, compilers, with editors L. Robert Davids, Bob McConnell, Ray Nemec, John Benesch Jr., and Bill Weiss. The Historical Register: The

Complete Major & Minor League Records of Baseball’s Greatest Players. San Diego

and San Marino: Baseball Press Books, 1998.

Net Shrine On-line.

New York Times. Obituary. December 19, 1961.

Ping Bodie files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at Cooperstown,

New York.

Shatzkin, Mike, and Jim Charlton. The Ballplayers. New York: William Morrow, 1990.

Full Name

Frank Stephen Bodie

Born

October 8, 1887 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

December 17, 1961 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.