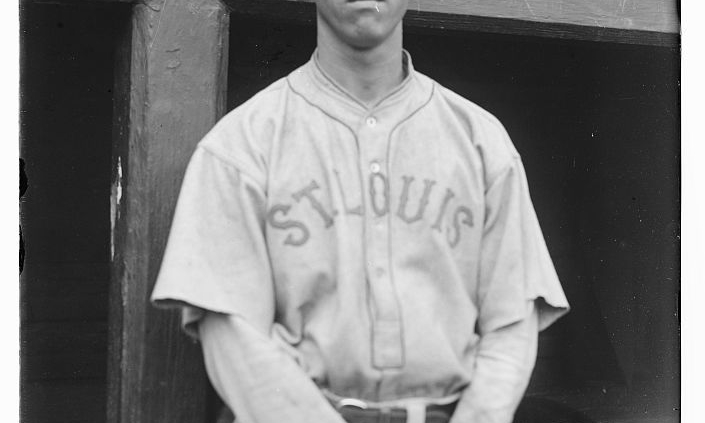

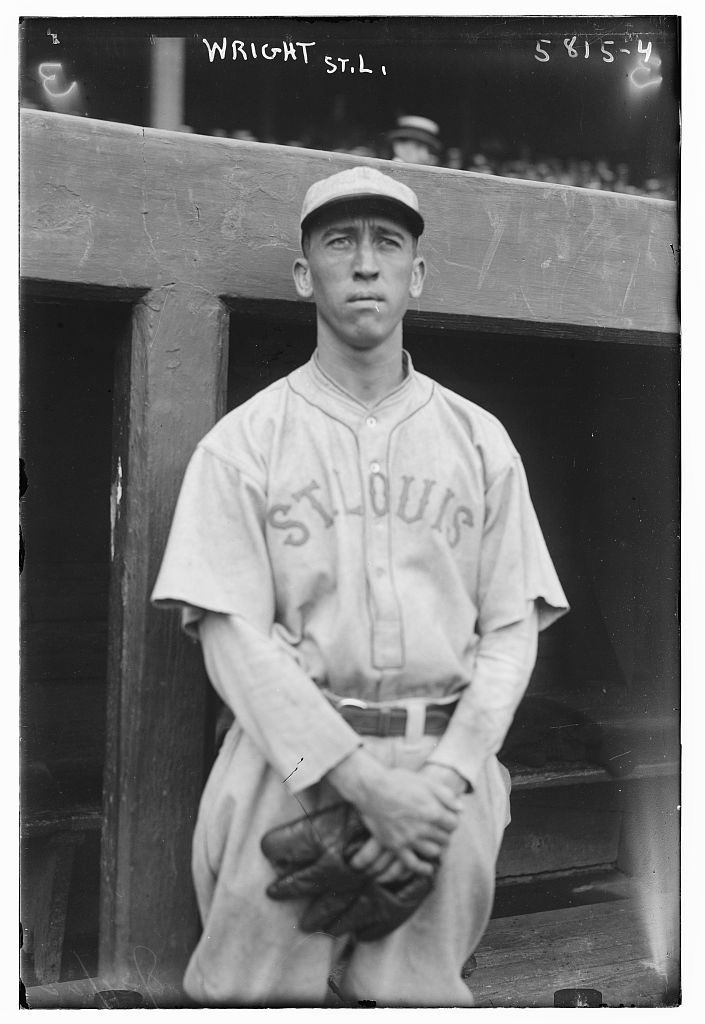

Wayne “Rasty” Wright

Wayne Bromley “Rasty” Wright spent his entire adult life pursuing his two passions, baseball and his alma mater, The Ohio State University. Wright was a star collegiate pitcher for the Buckeyes from 1915 through 1917. Going directly from college to the majors — a rarity throughout baseball history — he went on to pitch for the St. Louis Browns in five seasons (1917-1919, 1922-1923). He also spent all or parts of seven seasons in the minor leagues at the highest level then, AA. Wright played with, or for, future Hall of Famers George Sisler, Eddie Plank, Joe McCarthy, and Casey Stengel.

Wayne Bromley “Rasty” Wright spent his entire adult life pursuing his two passions, baseball and his alma mater, The Ohio State University. Wright was a star collegiate pitcher for the Buckeyes from 1915 through 1917. Going directly from college to the majors — a rarity throughout baseball history — he went on to pitch for the St. Louis Browns in five seasons (1917-1919, 1922-1923). He also spent all or parts of seven seasons in the minor leagues at the highest level then, AA. Wright played with, or for, future Hall of Famers George Sisler, Eddie Plank, Joe McCarthy, and Casey Stengel.

After retiring from pitching, Wright spent most of his remaining years in various baseball coaching positions at his alma mater. However, this baseball lifer’s time on earth ended far too early — and over the years, Wayne Wright has become a largely forgotten Buckeye.

Wright was born on November 5, 1895 in Ceredo, West Virginia, a town on the Ohio River. It lies across from South Point, Ohio in the tri-state area near Huntington, West Virginia and Ashland, Kentucky. Wayne’s grandparents, Robert Wright Sr. and Agnes, were Scottish immigrants. They moved to Ceredo from Massachusetts in 1858 at the urging of Eli Thayer, an abolitionist and Massachusetts congressman, who’d founded the town in 1857 on his antislavery principles. At that time the area was still part of an unpartitioned Virginia.

Robert Sr. loved Ceredo and took a job at a local sawmill. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, the population of Ceredo had grown to approximately 500 inhabitants. When war broke out, most of the immigrant settlers from the northeastern United States returned home. Yet Robert Wright Sr. and Agnes chose to stay amid the conflict, eventually raising ten sons and two daughters.

Following the war, the Wrights purchased a dry goods store. By 1895, they had built the largest mercantile store between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Most of the family worked at the store, which existed until 1931. In addition to working at the mercantile, the ten sons enjoyed playing the national pastime, baseball. The Wright brothers became excellent ballplayers, forming their own team, the “All Wrights.” The club played against various town and business teams for years.

Robert Sr.’s oldest son, Robert Jr., was born in Massachusetts in 1853 and moved to Ceredo at the age of four. He married “Belle” Ferguson in 1878. The couple had six children: five sons and a daughter. Wayne, like his father, brothers, uncles and cousins, began playing baseball at a young age. In the early 1900s, the sons of the ten Wright brothers were becoming old enough to join their fathers and uncles on the “All Wrights.” This included Wayne, who became a star pitcher for the team.

Wayne played high school ball and graduated from Ceredo-Kenova High School in 1913 (one of his older brothers, Sam, became the school’s first football coach in 1905). After graduating, Wayne made his way to The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio to further his academic studies and baseball career.

The slender righthander (5-foot-11, 160 pounds) arrived on the Ohio State campus in the autumn of 1913 for the 1913-14 school year. Freshmen were not eligible to play varsity sports at the time, so Wright played and pitched for the 1914 freshman team. He would have to wait until the 1915 season to showcase his talent for the varsity club, coached by the legendary L.W. St. John. In fact, Branch Rickey would seriously considered St. John to succeed Miller Huggins as St. Louis Cardinals manager in late 1917.1 Although Rickey and St. John were close friends, this deal never materialized. St. John went on to a long, successful career as a coach and athletic director at Ohio State.

Wright got off to a fine start in the spring of 1915. He posted victories against Oberlin College, Indiana University, and the University of Chicago. Having lost only to Illinois, which became his collegiate nemesis, his record stood at 3-1 heading into an intra-squad practice game on May 6. As a fine all-around athlete and offensive presence, Wright attempted to steal home on the front end of a double steal but broke his right leg. This unfortunate accident ended his sophomore season.

Wright made a full recovery, however, and proceeded to have an outstanding junior season in 1916. He was named to the all-conference team of the Western Conference (which preceded the Big Ten) as a pitcher.2 Although the Buckeyes did not win the 1916 conference championship, their future looked bright after they compiled a fine overall record of 13-2 and 4-2 in the Western Conference. Wright was the team’s star hurler and exhibited outstanding leadership qualities, which would serve him well in the years to come. At the conclusion of the season on June 8, 1916 Wright was rewarded for his efforts and leadership by being named squad captain for the 1917 season.

That season proved to be a breakout year for both Wright and the Buckeyes. Fifty players tried out for St. John’s 1917 squad, including football star Chic Harley, whose gridiron exploits contributed to the building and opening of Ohio Stadium for football in 1922. (Although it has undergone renovations and enlargement, Ohio Stadium remains the home of the football Buckeyes.) Fred Norton, the first four-sport letter winner at Ohio State, also became a key cog in the team’s success. (Alas, within a year of leaving Ohio State, Norton was tragically killed in action as a pilot during World War I. An airfield in Columbus was named in his honor.) Led by Wright’s pitching, Harley in right field, and Norton at shortstop, the Buckeyes were well stocked at every position.

Wright, however, was the star of the team. The hurler posted a spotless 10-0 record, utilizing his wide selection of breaking balls. In addition, he hit .357, trailing only Norton at .442 and Harley at .437, among regulars.3 In fact, Wright won a number of close games with his hitting. The cool and level-headed pitcher was known for moving with ease, never exerting himself unnecessarily.4 His dominant pitching, timely hitting, and leadership propelled the Buckeyes to an overall record of 14-1 and 6-1 in the Western Conference, resulting in the school’s first conference championship in baseball. The program would not win another outright championship until 1943, when Wright served as an assistant coach.

Major league scouts heavily pursued Wright in 1917. At least four clubs vied for his services. The St. Louis Browns took the first shot at the young prospect, and the Branch Rickey/Columbus connection was vital.

The Buckeyes played the Indiana Hoosiers on Friday, May 18, 1917, with the conference championship on the line. Wright squared off against Jack Ridley, captain and star hurler of the Hoosier squad. The game was played at Neil Park in Columbus, home of the Columbus Senators of the American Association. The game was a benefit, with part of the gate receipts designated for the French War Orphans’ Fund. Columbus native Bob Quinn, business manager and scout for the Browns, was in attendance. Quinn had succeeded Rickey with the Browns after a lengthy tenure with the Columbus Senators. While with Columbus, Quinn had built a network of teams around his Columbus headquarters that would serve as a “farm system.” Quinn would sign prospects and arrange for them to go to Portsmouth, Lima, or any number of other locations. His work was the prototype for the farm system that Rickey would eventually build.

Although Quinn also had his eye on Ridley, Wright was the Browns’ key focus.5 He was impressive, leading the Buckeyes to a 7-2 win and the conference crown.

On June 5, Wright received his varsity letter and gold watch fob as a conference champion. He was again named to the all-conference team. In three years, he lost only three games—all to Illinois—of which two were shutouts. In early June, a thoroughly impressed Quinn signed Wright to a contract with the Browns.

Wright picked up the nickname “Rasty” at some point during his professional career. Although the exact timing is not clear, there were at least three Wrights who bore the moniker before Wayne. As discussed in his SABR biography, William Smith Wright, who played in the majors in 1890 and in the minors as late as 1899, was the first. Following him were Clarence Eugene Wright (a big-leaguer from 1901 to 1904) and Floyd H. Wright (a minor-leaguer in 1915).

On June 20, 1917, Wayne Wright — age 21 — reported to manager Fielder Jones and the Browns. He made his major league debut on June 22, pitching three innings in relief against the Detroit Tigers, allowing four hits, one earned run, and no walks (he recorded no strikeouts). Wright made only one start in 16 games for the Browns that summer, pitching primarily in relief. He compiled an 0-1 record in 39 2/3 innings with an ERA of 5.45.6

In late September, Wright’s former college coach L.W. St. John and teammate Chic Harley visited with the Browns in Chicago while watching them play the White Sox. Manager Jones reported that Wright was the best fielding pitcher on the team. St. John also observed that Wright was effectively using the “slow ball,” which he had used sparingly in college.7

The season ended on September 29; however, Wright did return later to St. Louis to play in the city series against the cross-town Cardinals. Although the rookie’s individual statistics were not exceptional, Fielder Jones was impressed enough to sign Wright again for the 1918 season.

After the 1917 season ended, Wright returned to Columbus and Ohio State to resume his studies. He graduated in the winter of 1918 with a bachelor’s degree from the College of Arts and Sciences. He immediately entered medical school at Ohio State in the spring of 1918. Perhaps this was to avoid being drafted into the armed forces, as a result of World War One, which would have interrupted his baseball career. There does not appear to be documentation to support this. However, Wright did reach an agreement with the Browns to report in late May 1918 to avoid interrupting his schooling.8 He also signed on as assistant baseball coach at Ohio State, coaching the freshman team. Wright used this opportunity to stay in shape, working out with the team and playing in some intra-squad games and local scrimmages.

Wright reported to the Browns as scheduled in late May. On June 17, he finally made his first appearance of the season. It was a trying yet successful time for Wright. The Browns employed three managers that year: Jones, Jimmy Austin, and Jimmy Burke. The club improved upon 1917 by posting a 58-64-1 record in the war-shortened schedule. Wright far exceeded that winning percentage with a sterling record of 8-2 and an ERA of 2.51 in 18 games and 111 1/3 innings pitched.

During the season, baseball was declared a non-essential industry. Many players entered military service or did war-related work. Baseball made the decision to close prior to being forced to do so by the Federal government. The abbreviated season ended on Labor Day.

Although he dropped his last two decisions, Wright had won five consecutive decisions on the mound before that. The Sporting News considered him to be one of the best young arms in the majors.9

Wright again returned to Ohio State to continue his medical studies. With the impressive 1918 season behind him, he was asked to return to the Browns for the 1919 season. However, it turned out to be a trying one for Wright. Pitching for manager Burke, he struggled to a record of 0-5 and an ERA of 5.54 in 24 games and 63 innings pitched. The Browns finished five games below .500 in a 140-game schedule.

After the conclusion of the season, the Browns decided that Wright needed more seasoning before he could again become a reliable big-league pitcher. On January 7, 1920, they traded Wright and pitcher Ernie Koob to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association in exchange for another pitcher, Dixie Davis.

It must have been a huge disappointment for Wright to be sent to the minors. However, pitching for future Hall of Fame manager Joe McCarthy, Wright flourished. In 1920 he was a workhorse, pitching 280 innings in 52 games, winning 15 and losing 15 with a solid ERA of 3.05.

Louisville was again the destination for Wright in 1921. Once more pitching for McCarthy, he saw plenty of action: 196 innings in 48 games. He compiled a 13-15 record although his ERA expanded to 4.68. Nonetheless, the Browns were once again impressed enough with Wright’s work to repurchase his contract for the 1922 season. A team on the rise, they wanted Wright back to bolster their pitching staff.

Lee Fohl — Bob Quinn’s most trusted baseball man from their days in Columbus — had taken over as manager of the Browns in 1921. They finished that season with a respectable record of 81-73, placing third behind the pennant-winning Yankees and second-place Indians. The 1922 team had a breakout season and was arguably the best in the history of the largely downtrodden franchise, with a record of 93-61. Still, this strong record was only good enough to finish in second place, one game behind the Yankees in the American League. The Browns were led by the great Hall of Fame first baseman George Sisler, another Ohioan. The club boasted another man from Columbus, starting shortstop Wally Gerber.

Wright had another very good season in 1922, going 9-7 with a sharp ERA of 2.92, fourth best in the American League for pitchers with 150 innings or more. He pitched in 31 games, starting 16, completing four and saving five others in relief. Wright’s sound fielding continued — he made only one error during the season. Not a flamethrower, Wright pitched to contact but his hits per nine innings were superb by 1922 standards (fifth for pitchers with 150 innings or more.). In 1922, he had only 44 strikeouts, while walking 50 and allowing 148 hits in 154 innings.

After his good year, it seemed like Wright — still just 26 — was headed for a long career with the Browns. However, this was not to be.

In 1923, Wright once again was late reporting to the Browns because of his schooling and assisting with the Ohio State baseball team. The Browns did not have the success they had in 1922, finishing below .500 (74-78). Fohl was replaced during the season by Jimmy Austin. Wright pitched in 20 games, compiling 82 innings. Though he was 7-4, his ERA ballooned to 6.42. His final major league game occurred on October 4, 1923. He started against the Cleveland Indians and lasted six innings, giving up eight hits and eight earned runs.

Across his five seasons in the majors, Wright appeared in 109 games, starting 43. He won 24 games while losing 19, with a somewhat subpar ERA of 4.05 reflecting his ups and downs. In addition to his good fielding, his hitting also remained better than average for a pitcher: 26 for 160 (.195).

Wright, who was experiencing shoulder problems, sat out the 1924 season in voluntary retirement. He went back east to West Virginia, where he played for and managed Northfork, a semipro team.

However, by this time his rights belonged to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League (PCL). That January, the new Browns manager — George Sisler — had decided to make a trade. He’d received good scouting reports on catcher Tony Rego and pitcher George Lyons, and liked what he saw himself of that battery.10 St. Louis sent five players to L.A. in exchange for the pair.

The deal turned out quite lopsided largely because the Browns gave up pitcher Charley Root, who had shown little as a rookie in 1923 but went on to win 201 games in the majors. But Rasty Wright alone made the trade look good for the Angels, serving them well for four seasons. In 1925, with his shoulder healed, Wright came out of retirement. He hurled in L.A.’s Wrigley Field for manager Marty Krug. During his time with the Angels, he pitched in 121 games and logged 782 innings, winning 47 games and losing 42. His best season in the PCL was in 1926. In 31 games and 222 innings pitched, he won 19 games and lost 7 with a fine ERA of 3.08.

Wright’s final year with the Angels was 1928. That fall he returned to Columbus to resume his medical studies at Ohio State. There is no record that he finished medical school or practiced any type of medicine. However, in early 1929, baseball coach and athletic director L.W. St. John offered Wright a permanent position as assistant baseball coach. Wright wholeheartedly accepted. It was not long before St. John decided that his own multiple duties were too much to handle. Before the start of the 1929 college season, he named Wright head baseball coach. Thus, Wright became one of only three former captains to assume that position at Ohio State.11 The 1929 team finished with a record of 4-6 in the conference and 11-8 overall.

Yet once again, Wright’s pro playing career was not quite over. After the 1929 college season was complete, he joined the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association. The Mud Hens were managed by a legend-to-be, Casey Stengel. Stengel was known to relish veteran players who could provide experience and leadership to the youngsters. Wright appeared in 22 innings over six games and posted a 2-3 record. This officially ended his professional playing days.

Wright returned to Ohio State for the 1930 season. His squad posted an overall record of 12-6-1, followed by marks of 8-5 in 1931 and 6-7 in 1932. Their conference records were 4-4, 4-3, and 3-6. This ended Wright’s four-year stint as head coach of the baseball Buckeyes.

In the midst of the Great Depression, football attendance and revenue dropped substantially during the 1932 season. With football revenue down, the athletic department was forced to make deep cost cuts. Lynn St. John was able to retain the baseball program, but on the condition that the head coach’s contract not be renewed for the 1933 season. St. John moved Floyd Stahl and Wesley Fesler in from other areas of the department to assist him, with Stahl ultimately given the head role. Wayne Wright had become a victim of the Depression.

With wife Margaret, one daughter and four sons to provide for, Wright was forced to seek permanent employment. He found such with the Standard Oil Company and from 1932 to 1948 managed at least two service stations in the vicinity of the OSU campus. It is probable that the Depression’s economic impact ended his aspirations of finishing medical school.

However, Wright’s love for his university and baseball prompted him to return as a volunteer assistant coach for the next 14 years. He assisted Floyd Stahl from 1933-1938, Fred Mackey from 1939-1944, and Lowell Wrigley from 1945-1946.

Through all of his years attending school, coaching baseball, and managing service stations, Wright lived in the neighborhood of the OSU campus. His hobbies were hunting and golf. He consistently scored in the 80s in golf in various competitions around Columbus.12

Wright retired from coaching after the 1946 season because of declining health. He was eventually diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. After suffering for more than a year, he passed away on June 12, 1948, at the age of 52. Once again close to his alma mater, he died at University Hospital. The funeral was held at D. Harvey Davis Funeral Home, with burial at Union Cemetery East in Columbus. In addition to his wife (Margaret) and five children (Wayne B., Jr., Robert, Harold, Donald and Mary Belle), he was survived by a sister and four brothers.13

Today, Wayne B. “Rasty” Wright lives on mainly in the record books. Alas, he remains largely unknown in the Ohio State community.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Newspapers or Magazines

The Columbus Dispatch

The Makio; 1918; Ohio State University

Cole, Bruns; sportswriter. The “All Wright Team,” The New Crescent Newspaper; Town of Ceredo, West Virginia

The Ohio State University Lantern

The Ohio State University Monthly

The Sporting News

Online

Baseball-Reference.com

OhioStateBuckeyes.com>baseball

Retrosheet.org

Archives

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Wayne B. Wright

Personal Correspondence

Mayor Paul A. Billups, Town of Ceredo, West Virginia

Union Cemetery, Columbus, Ohio

Notes

1 “A College Coach to ‘Cards?’ L.W. St. John of Ohio State May Manage the St. Louis Team,” Kansas City Star (Kansas City, Missouri), December 5, 1917: 12.

2 OhioStateBuckeyes.com>baseball

3 Parker M. Stokes, “Baseball Season,” The Makio (The Ohio State University), 1918: 167

4 Parker M. Stokes, “Baseball Season,” The Makio (The Ohio State University), 1918: 1663 .

5“Quinn Will Look At Work Of Wright In Hoosier Game,” Columbus Dispatch, May 18, 1917: 30.

6 Baseball-Reference.com shows Wright pitching 42 games and 285 innings in Class A ball in 1917, but that does not fit with the known facts.

7 “Wayne Wright Makes Good in Big League,” Ohio State Lantern, September 25, 1917: 4.

8 “Wayne Wright Makes Good in Big League.”

9 “Sporting News Carries Story About 1917 Championship Pitcher,” Ohio State Lantern, February 17, 1919: 1.

10 Wire service report carried by various newspapers, April 21-25, 1941.

11 OhioStateBuckeyes.com>baseball

12 Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Wayne B. Wright.

13 Columbus Dispatch, June 13, 1948: 30.

Full Name

Wayne Bromley Wright

Born

November 5, 1895 at Ceredo, WV (USA)

Died

June 12, 1948 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.