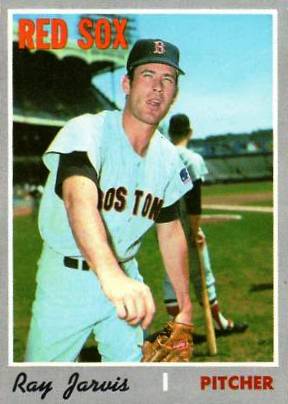

Ray Jarvis

When considering Rhode Island natives who played major league baseball, you can’t get much closer to the heart of Rhode Island than with Ray Jarvis, who grew up playing baseball on the State House lawn. Ray was born in Providence on May 10, 1946 and grew up on Smith Hill. Most of the kids in the neighborhood played baseball, most often on the side lawn of the state building, playing from 9:00 in the morning until dark, with breaks for lunch and dinner. “And when it got dark, we used to go into the parking lot and play,” Ray recalled in a September 2009 interview.

When considering Rhode Island natives who played major league baseball, you can’t get much closer to the heart of Rhode Island than with Ray Jarvis, who grew up playing baseball on the State House lawn. Ray was born in Providence on May 10, 1946 and grew up on Smith Hill. Most of the kids in the neighborhood played baseball, most often on the side lawn of the state building, playing from 9:00 in the morning until dark, with breaks for lunch and dinner. “And when it got dark, we used to go into the parking lot and play,” Ray recalled in a September 2009 interview.

“The people from the State House used to come out and watch us. The governor at the time – Governor Roberts – he was a Democrat. I can remember being in the third grade and we used to have this security guard [who] used to throw us off the grass all the time. And then the people that were cutting grass or watering grass, they would complain. They’d throw us off. They thought we were going to make patches for the bases. Which we eventually ended up doing, because we just played so often. One day we went up to Governor Roberts’ office. Along with two or three other guys, we got an audience with him and we asked him if we could play. Because we had no playground in that area. It was before Little League actually. So we went up there and he said yes. The following year, he was defeated. A new governor came in and it was a Republican, Christopher DelSesto. The same thing happened again. We went there, and the same thing happened. He allowed us to play again.” [Interview with Ray Jarvis, September 16, 2009. All quotations from Jarvis come from this interview unless otherwise attributed.]

With true bipartisan backing, the games went on. Ray’s father was a policeman and his mother a traffic crossing guard. Ray had a younger brother, about a year and a half younger. The parents divorced when Ray was about eight years old, and though he saw his father weekly – and played a little catch with him – it was his mother who brought up the two boys as a single parent, taking as many as two or three jobs at a time. She worked as a receptionist/switchboard operator for the State of Rhode Island, then moved to B.B. Greenberg, a jewelry company where she also served on the switchboard. On weekends she worked for Louie’s Kosher Catering, often doing two or three bar mitzvahs and weddings. “She sacrificed so that I could play ball,” Jarvis appreciates. “And that my brother could do the things that he was doing.” Ray’s brother Bob wasn’t that interested in sports. After a stint in the Coast Guard, he worked for the Fire Department in Providence. He went back to school and got his degree, and on retirement from the department, he became a schoolteacher.

Young Ray played all the positions– infield, outfield, catcher, pitcher. “I played from the fifth grade for St. Patrick’s CYO. I played baseball and basketball. It was primarily a basketball neighborhood that I lived in. Great basketball teams. They won the New England and state championships year after year. I played CYO baseball, I played Babe Ruth League baseball, and then I went and played in high school and I played American Legion at the same time, and then after the completion of my junior year, I played down the Cape, in Chatham.” By that time, he’d become a pitcher, and – apparently – an impressive one. The Hartford Courant later told of Jarvis facing batters for Chatham and “standing them on their ears.” [Courant, June 8, 1969]

“I started pitching probably in the sixth or seventh grade, for the CYO team, and every year I’d pitch a no-hitter in one of those amateur things. I pitched all the games in the eighth grade. I could always throw the ball pretty well. When I got to [Providence’s Hope] High School, I knew certainly I was going to be a pitcher.” The experience in the Cape Cod League was good, exposing Ray to a much higher level of play. It was the summer of 1964. “We had a great team there. I wasn’t used to guys that could hit the ball out of the ballpark, and make the plays. There were some great athletes.”

It was at Chatham that Ray first caught the eye of Red Sox scout Jumpin’ Joe Dugan, a former major league infielder for 14 seasons. Dugan later told the Monitor’s Ed Rumill, “I saw him pitch in high school and signed him in June of 1965. This was before the free-agent draft. He was on the open market. Anybody could have signed him. But the high-school coach was a friend of mine and maybe that gave me the inside track.” [Christian Science Monitor, May 2, 1969] In fact, the first amateur draft was in early June 1965, just as Ray graduated from high school. Perhaps Dugan was simply saying that before 1965 anyone could have signed Jarvis. The Sox took him in the 18th round.

Ray’s high school coach was Paul Donovan, but Ray wasn’t aware of his friendship with Dugan. He’d never spoken with Dugan before the offer came. His signing bonus was $7,500, a sizable one by the standards of the day. Boston’s first-round draft pick (fifth pick overall) was Billy Conigliaro, who signed for a reported $50,000. Ray remembered, “All in all, it was more money than I had ever seen. My mother worked. It was a lot of money.” By no means was it all about the money, he adds, but he was impressed again when after the Red Sox sent him to Harlan, Kentucky to pitch rookie-level baseball for the Appalachian League’s Harlan Red Sox, he got his first paycheck: “Five hundred dollars for the month. I can remember telling the other players, ‘Look at this! Five hundred dollars.’ If they only knew, I would have done this for nothing. But that was the kind of attitude that a lot of people had back then. It wasn’t about the money. It was more about having the opportunity to play. I actually loved the game, I would have…I loved it. There’s no question about that.”

Ray was still finding his feet. Ten home runs in 93 innings contributed to an earned run average of 5.81, though he did put up a 7-5 record. He led the rookie league in games started but also in hit batsmen. “I was ready because of the experience I got in the Cape Cod League,” he told Rumill. “I was playing with older players, some of whom had been pros.” [Christian Science Monitor, May 2, 1969. Rumill, one of the better Boston sportswriters, may have inadvertently conflated two things here. There were no pros who played in the Cape League.] He had a good enough year that the Red Sox promoted him to Single-A, but Uncle Sam called, and Jarvis spent six months in 1966 in the National Guard. His obligation took the full season away from him – but was much better than the alternative, which was likely to be taken into the Army and sent to Vietnam.

After eight weeks of basic training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and eight weeks advanced artillery training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, Jarvis was proficient in firing a 105 howitzer and a 155 howitzer. “That’s something I could use today,” he laughs. Jarvis and the Red Sox had to jump through some hoops in order for Ray to continue to play ball. Because the team wanted to send him to other states, and the National Guard is a state unit, he transferred out of the Guard into the US Army Control Group in 1966. The following year, President Johnson abolished the control group and ordered all inactive reservists to enter reserve unit or active duty. Ray joined the Army Reserve and had to attend regular Reserve unit meetings – typically twice a week – for six years. The Sox assigned him to the Waterloo Hawks (Midwest League) in Waterloo, Iowa and none of the local units wanted to take him – after all, he might be sent on to some other team in the system, in some other state. Jarvis got a lawyer, and found a Reserve unit in Connecticut which accepted him. He stayed in that unit until 1971, when he transferred to Salt Lake City.

Unlike someone with a job in a fixed location, the travel involved in baseball at all levels of the game made for great logistical nightmares, trying to play baseball but still meet his obligations. “The unit I was in had drills on Wednesdays and on weekends, and if you missed what they called five meetings in the course of a year, you would be placed on active duty. So the Red Sox used to fly me, and other players, back and forth to wherever towns we had our meetings in. We would have to do our meetings and then come back and play. That was more than a distraction.” It was a distraction that continued for the rest of Ray’s baseball career.

After the “lost summer” of 1966, Jarvis played in the fall instructional league in Florida. In 1967, while Boston was in pursuit of the Impossible Dream, Ray was living a dream of his own, with the Waterloo Hawks. He started 26 games and put up a record of 15-8, with a 2.04 ERA. What more could a young player ask for? Not surprisingly, he was named to the league’s all-star team.

Apparently, the Red Sox wanted to see a little more, because he wasn’t advanced in the system. In 1968, he was assigned laterally to another Single-A ballclub, the Carolina League’s Winston-Salem Red Sox, and he seemed to flounder there. Though his ERA was a respectable 3.49, it was while compiling a miserable 0-8 won/loss record. The team itself didn’t play that well in ‘68; they posted a 56-81 record. Why had Jarvis had such a bad record? And why did he then get advanced to Triple A?

“The best I could explain that: we had two teams. We had an offensive team and a defensive team. The defensive team couldn’t hit, but the offensive team couldn’t field. I was a ground-ball pitcher, so in many of those games my ERA was pretty good but I just couldn’t win, because they’d put people out there but we just couldn’t seem to score more runs than the other team. I pitched well, and it came time to…this was interesting. About halfway through the year, I got promoted to Triple A. And Kasko was the manager. I guess they asked Bill Slack [manager at Winston-Salem], “Send us up somebody, the best guy you have” and he sent me. When Kasko found out that I was 0-8, well, he wasn’t real happy about that, I don’t think. He never verbalized that but I could see from the look in his eye, how in the hell did this guy get here? He’s 0-8. But anyway, I ended up, I think, being 6-6.”

Despite climbing two rungs up the ladder to the Triple A Louisville Colonels, under Kasko, Jarvis finished 6-6 with a 3.28 ERA. His fine half-season got him promoted to the 40-man roster in October. Fellow pitcher Mike Nagy was included in the group promoted, as was fellow New Englander Carlton Fisk. In 1969, Ray received his first invitation to spring training with the big-league club.

There were openings on the Red Sox pitching staff in 1969. Jose Santiago looked to be lost for the season due to elbow surgery, and only Ray Culp and Jim Lonborg were back and truly contributing. They later picked up Sonny Siebert and Vicente Romo in a mid-April trade, but there still had been room for Nagy, Jarvis, Fred Wenz, and maybe one or two others – despite the Courant’s Bill Lee writing that Jarvis’s stint at Louisville had been “without setting any fires.” [Hartford Courant, April 2, 1969] Jarvis recalled how he learned he’d made the major leagues: “I was probably the last guy to make the team. All I know is, when all the dust cleared the last day of spring training, I didn’t get cut so I guess that meant I made the team.”

Ray remembered the first time in his life he’d ever been cut by a team. It was in Deland, Florida for spring training with Louisville. “It came time for the cuts, and I was just cut. I expected they would call you in, and they say, well, you know, you’re doing that…and you should go to work on this – like, OK, you’re going to Ocala and you’ll be with Winston-Salem. They didn’t do anything, it was just, ‘Get your bags and go over there.’ In ’67, I remember being in Ocala and they used to have a big locker room and there was three metal hangers that would have names on there, and the clubhouse guy used to go in, in the morning, and rip the guys’ names off who got cut. And if you showed up and your name wasn’t…you’d just go to the office and pick up a ticket and then leave. That’s how they cut people. It’s funny now, but not too funny every morning if you’re on the edge.”

On Opening Day 1969, however, Ray Jarvis was in uniform and a member of the Boston Red Sox. Ray’s major-league debut came in the season’s seventh game, on April 15 against the Orioles, entering to pitch the fifth inning with the Red Sox behind, 4-2. The first batter he faced was Frank Robinson, who tripled to Fenway’s right field – but Jarvis buckled down and got three ground outs, stranding Robinson on third. He allowed a single run in the sixth. Ray was due up to bat in the bottom of the sixth, but Dalton Jones pinch-hit for him and drove in a run.

Jarvis pitched in each of the next two games, too, and then a surprising 8 2/3 innings of relief against the Indians on the 20th. He came into the game with three runs scored and the bases loaded in the first inning. He pitched out of that jam, and then the rest of the game, giving up just two hits and one earned run and recording his first major-league win. He also struck out five times as batter, a major league record he still shares.

Granted his first big-league start on April 28, Jarvis pitched a very strong game in Yankee Stadium, allowing only one run on four hits in seven innings – but was tagged with the loss because Fritz Peterson threw a complete-game, three-hit shutout. The game had offered another opportunity that Ray hadn’t realized at the time. He struck out his first time up, and that made for six consecutive strikeouts. The record at the time was seven. “If I had known that,” he jokes, “I would have struck out a couple of more times.” Instead, he grounded out his next two times up, before resuming the strikeout parade on May 3. It was still early in his career and the whiffs weren’t really noticed. Manager Dick Williams was pleased, both with Jarvis and fellow right-hander Mike Nagy. The Monitor‘s headline read: “Jarvis: an exciting young arm at Fenway.” [Christian Science Monitor, May 2, 1969] The Courant’s Bill Lee was looking at a pitcher who had “four mostly undistinguished minor league seasons behind him” but had still started the ’69 season quite well. [Hartford Courant, May 9, 1969]

In June, pitching coach Darrell Johnson suggested that it might not last: “We’ve been lucky so far with Jarvis and Nagy. We’ve been winning while they have been pitching and learning. They didn’t always get the victory, but at this pointing their careers, the experience they get from working regularly is worth even more.” [Christian Science Monitor, June 19, 1969] Nagy finished the season 12-2, reflecting more than just luck. And with Jarvis, his ERA was under 4.00 through June. When the season ended, he had regressed to 4.75 with a 5-6 record. He walked more batters than he struck out, something that plagued him throughout his career. (At the plate, he was 2-for-29, with two singles, and 19 strikeouts.) The second of his two hits won him his fifth game, against the Orioles–he batted in the game-winning run and then drove in another with a sacrifice fly. Ray won the game, 6-1, but the one run was an odd one. Don Buford homered with a man on base, but Buford was ruled out because in confusion as to whether or not Tony Conigliaro had actually caught the ball before falling into the right-field stands, Buford had passed runner Dave May on the basepaths. Buford was ruled to have singled. But did May actually score? He never did complete his circuit of the bases. Plate umpire John Flaherty said after the game that had the Red Sox thrown the ball to second base, he would have ruled May out for failing to touch the base. The Sox didn’t, though, and Jarvis failed to get the shutout that could have been his. [The July 21 Hartford Courant has a good account of the play.]

From late in July into early August, Jarvis joined the 76th Division Army Reserves training at Fort Dix for his required two weeks of duty. Ray and his wife – with whom he’d gone to school since the eighth grade – maintained their home in the Rhode Island capital. There were times the schedule hurt him. The July 24 game was a Thursday night game in Seattle; Ray had been flown back East so he could attend to his Wednesday night meeting, then flown back across the country the next morning in time to pitch soon after arrival. He gave up seven runs (six earned) in just 2 1/3 innings; he was frazzled. Later that night, he was back on a plane to re-join his unit for the Saturday drill. Williams threw him into another game, on August 10, his first day back from the Reserves. It should be no wonder that his pitching deteriorated as the season wore on. [Hartford Courant, August 15, 1969]

This was also the year that Jarvis first developed shoulder problems. “I hurt it in spring training, I believe, and I got a cortisone shot. I got several cortisone shots while I was playing in ’69. I was taking muscle relaxers, blood thinners, a thing called Indocin, sterile Darvon. I was taking a lot of stuff just so I could play. I don’t blame the Red Sox. I don’t blame anyone else. I’m just trying to stay there. So many guys never get a shot, and once I was there, I wasn’t about to….So I continued to pitch whenever they asked me to pitch, and just do the best I could do. Some days I started, sometimes I pitched long relief, sometimes I pitched short relief. Whatever they wanted, I would do. I was hurting myself more and more. I was taking these shots and I was taking these pills, and I couldn’t even turn the wheel of my car. I couldn’t pick anything up from the back seat. I couldn’t put my arm on the armrest. But I was damned if I was going to tell them I couldn’t pitch.”

Did trainer Buddy LeRoux know? “They knew. I used to go to the trainer, and I would say, ‘My arm hurts when I go like this, Buddy’ and he would say, ‘Well, don’t go like that.’ They would send you to the doctor and you would get a cortisone shot. They’d give you ultrasound and they’d put the heat packs on and they’d put this horse liniment on and you’d take the pain medication and you’d take something to reduce the inflammation, and then you’d go out there and play. A lot of players played with pain back then. It was a different era. And there were plenty of players to take your place.”

Finally, perhaps aggravated by all the travel, Jarvis went on the disabled list after his August 12 stint in Chicago, next appearing in a game 40 days later.

Ray started the 1970 season with the Red Sox, but by late May Jose Santiago was ready to come back from the surgery that had kept him out of action for just over a year. Jarvis had appeared in 12 games, and had a 2.92 ERA working in relief. On May 27, Santiago was called up from Louisville and Ray was the man optioned out. He worked most of the year for the Colonels again, 4-6 with an uninspiring 5.22 ERA. On September 1 he was one of seven players called back up. He got into three more games, adding another 3 2/3 innings to his record, touched for three earned runs in his final game.

That game turned out to be his last in a Red Sox uniform. Less than a month later, in mid-October, he was packaged in a large six-player trade to the Angels. It was a Jarvis/Jarvis, Tatum/Tatum trade, and a bit of a shocker. Boston’s hometown hero Tony Conigliaro was sent westward, with Ray Jarvis and Jerry Moses. Boston picked up Ken Tatum and Doug Griffin – and a player unrelated to Ken named Jarvis Tatum.

Ray never played in the majors again. He went to 1971 spring training with the Angels, and was cut on the final day. “We probably had 10 pitchers on the team that had pitched in the major leagues the year before. They loaded up with good pitchers.” Jarvis was assigned to the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, playing for the Salt Lake City Angels. He was 4-4 but with a poor 5.88 ERA, in part because he only struck out 18 batters while walking 33. There was another reason, though. “There were three Triple A leagues in the country. There was the Pacific Coast League, there was the American Association, and there was the International League. The players are all comparable players, ability-wise. If you look at the number of .300 hitters, there were three times as many .300 hitters in the Pacific Coast League. The home runs were probably three times higher. And the ERAs were higher than the lowest ERA…the lowest ERA in the minor leagues would be 1.9, 1.8, and there it was probably 3.1 or 3.2. What happened was they were experimenting in spring training with what they called the rabbit ball. Pitchers were dominating the game. They lowered the mound.

“What they did was they wound the balls tighter so they would go faster. Every Wednesday in spring training, they would use these experimental balls. They were tying to increase the offense. So they put these balls in, and they would compare them to other games. And the scores on these Wednesdays in spring training were like 9-7, 8-6. They were higher-scoring games, because the balls were livelier. So when the season concluded, I guess they made an agreement with Reach or Spalding or whoever made them that they would utilize these balls. And I believe they put them in the Pacific Coast League to use them. Players were hitting balls over the light towers. I don’t mean over the fence, but over the light towers. Regularly. There were regularly crushing the ball over the light towers. Well, anyway…I’m not trying to justify why my….

“I left in August because my arm hurt. I went to a doctor on my own in Eugene, Oregon. I went there to get a shot. At this point, I was getting shots – I was getting some on my own – I was trying to hang on. I told him I needed three shots. He said to me, ‘Do you have a college education?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t. Why?’ And he said, ‘Well, you ought to think about getting one, because your career is over.’ He was the first guy that told it like it was. They’d just say, ‘OK, we’ll give you some more of this. Give you so many cc’s of this….’”

Jarvis still wasn’t ready to throw in the towel. He was absolutely crushed.” He took the rest of the year off, rested, and rehabbed. He tried to become more of a finesse pitcher, but had been so used to aggressively challenge batters by trying to blow the ball past them that it was hard to dial back a couple of notches. The moment a bit of adversity hit in his pitching, he’d revert to his earlier approach. He couldn’t make it back, and was released during spring training of 1972. He was 25 years old, with two children, a wife, a house to look after. “I was scared to death. I didn’t know what I was going to do for the rest of my life, because all I ever wanted to do was play ball, and that was gone. I didn’t know what I was going to do to make a living, to survive.”

He went into sales, perhaps an apt choice given that he could channel some of the drive and doggedness that had served him as a ballplayer. He went back to school long enough to get a real estate’s broker’s license, but couldn’t afford to take the time to work to build up enough of a clientele that he could afford to work on straight commission. He started selling sporting goods and other things, then landed a job with Jostens selling class rings around the Rhode Island for quite a few years, working with corporate accounts as well. Jarvis worked in the metal business as a sales rep for brass and copper distributors, and then selling nickel alloys. He worked for Herff Jones for a while, for Balfour, and finally for VDN, a German company whose name translated to United German Nickelworks, becoming a regional sales manager for VDN.

At the same time, he worked as assistant baseball coach at Bryant College for four years from 1976, and was the pitching coach for Providence College from 1989 to 1993. In the early 1990s, he burnt out on sales and took a position in the security department at Providence College as a supervisor, and Sgt. Raymond Jarvis had been there since that time.

He’ll always root for the Red Sox, he says, but he’s not really a fan – the way he is with the New England Patriots. With baseball, he didn’t develop a lot of enduring friendships; players come one day and are gone the next. When he watches a game, he wants it to be a meaningful one, and even then he can’t help but study the approach the pitchers take as the game unfolds, where he’s trying to locate, and so forth. Naturally, he looks back with regret that he wasn’t able to do more during his time in organized baseball, but holds no one at fault. He knows he was fortunate to have a chance to play as much as he did. He also knows that the attitude he brought to the game was what got him there, and that if he’d approached it differently, he probably wouldn’t have made it. “I did what I had to do to get there, and, you know, c’est la vie, that’s the way it is.”

Ray Jarvis fought cancer in his later life and died in Grapevine, Texas on April 24, 2020.

Sources

For this story, the author relied heavily on a long interview with Ray Jarvis, with followups via e-mail, and on several newspaper accounts, mentioned explicitly within the text.

Full Name

Raymond Arnold Jarvis

Born

May 10, 1946 at Providence, RI (USA)

Died

April 24, 2020 at Grapevine, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.