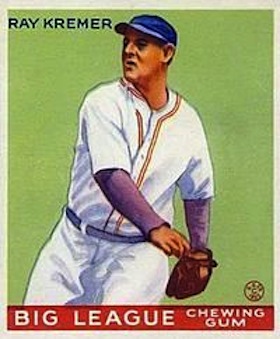

Ray Kremer

Right-hander Ray Kremer can lay a legitimate claim as being the best pitcher in big-league history to debut in his 30s. After failing in a spring-training tryout with the New York Giants in 1916, Kremer logged more than 2,100 innings and won over 100 games in the Pacific Coast League in the late 1910s and early 1920s, but was overlooked as a warm-weather pitcher. Given a second chance by the Pirates, he debuted as a 31-year old in 1924, won 18 games, and led the National League with four shutouts. En route to leading the senior circuit twice in victories (1926 and 1930) and earned-run average (1926 and 1927), and setting a big-league record with 22 consecutive victories at home, the durable Kremer was a model of consistency, winning 15 or more games for seven consecutive seasons and logging at least 200 innings for eight straight years. The workhorse on two pennant-winning teams, Kremer was one of the Pirates’ World Series heroes in 1925, winning Games Six and Seven to secure the Corsairs’ first championship in the live-ball era.

Right-hander Ray Kremer can lay a legitimate claim as being the best pitcher in big-league history to debut in his 30s. After failing in a spring-training tryout with the New York Giants in 1916, Kremer logged more than 2,100 innings and won over 100 games in the Pacific Coast League in the late 1910s and early 1920s, but was overlooked as a warm-weather pitcher. Given a second chance by the Pirates, he debuted as a 31-year old in 1924, won 18 games, and led the National League with four shutouts. En route to leading the senior circuit twice in victories (1926 and 1930) and earned-run average (1926 and 1927), and setting a big-league record with 22 consecutive victories at home, the durable Kremer was a model of consistency, winning 15 or more games for seven consecutive seasons and logging at least 200 innings for eight straight years. The workhorse on two pennant-winning teams, Kremer was one of the Pirates’ World Series heroes in 1925, winning Games Six and Seven to secure the Corsairs’ first championship in the live-ball era.

Remy Peter Kremer was born on March 23, 1893, in Oakland, California, the third of five children born to Nicholas and Mary (Gargaden) Kremer. Both parents were born in France, emigrated with their families to the United States in the early 1870s, and settled in Northern California, where they met and married in 1885. Nicholas operated a brass and zinc foundry and was considered a pioneer in making brass statues found throughout the area. A homemaker, Mary raised five children, Nicholas Jr., Jacques, Remy (as his parents called him), Marie, and Yvonne. Expected to follow his father’s career path (as his older brothers had), Ray attended Polytechnic High School in Oakland. But growing up just about 1½ miles from Freeman’s Park (and beginning in 1913 the newly constructed Oakland Ball Park), where the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League played their home games, Remy dreamed of playing baseball. Given the year-round temperate climate, Kremer began playing baseball in local winter semipro leagues while a high-school student. Tall, athletic, and blessed with a powerful right arm, he was groomed as a pitcher. In 1913 he guided the Sebastopol Warriors to a semipro title, defeating Petaluma, led by future major-leaguer pitcher Dutch Ruether. Their paths crossed again in the 1925 World Series.1

Lauded as the “most promising youngster” in the Oakland area, the 21-year-old Kremer began his professional baseball career in the spring of 1914 when he was signed by Harry Wolverton, a former big-league third baseman and the manager of the Sacramento Wolves of the Pacific Coast League.2 Playing against older, seasoned professionals, Kremer struggled, winning just twice in ten decisions and posting the league’s highest earned-run average (5.20 in 136? innings) while splitting his time among starts and relief appearances. When the team declared bankruptcy the following the season, Kremer was sent to the Vancouver Bears of the Class B Northwestern League. With the threat of a league-wide baseball player strike, Kremer quit in midseason sporting a 7-5 record and an impressive 3.14 ERA. He returned to Oakland and resumed pitching in semipro ball. Known as a fast, hard-throwing pitcher with good control, Kremer earned the nickname Bush Wiz (for bush league) which gradually evolved into Wiz and remained with him for his entire career.3

Kremer was signed by the New York Giants in the offseason and reported to Marlin Springs, Texas, for his first big-league spring training in 1916. While there he developed a severe case of rheumatism that caused his ankle and wrist joints to swell, making walking, let alone pitching, an excruciating task. Consequently, Giants manager John McGraw assigned Kremer to the Rochester Hustlers of the International League. Soon healthy enough to pitch, Kremer revealed his potential by defeating the Giants, 3-2, in an exhibition game shortly before the regular season opened. Soon thereafter, his joint pain returned. Kremer struggled with the Hustlers, winning two of six decisions and logging just 35 innings, before McGraw released him from his contract in midsummer.4 Dejected, Kremer headed back to Oakland, but was admitted en route to a hospital in Altoona, Pennsylvania, for treatment. (One report said he was suffering from a “nervous breakdown.”)5

“The Frenchman” (as sportswriters often called him during his big-league career) was a rugged, good-looking man with a weatherbeaten face, brown eyes, black hair, and a tanned, dark complexion. In 1917 he married his local sweetheart, Beulah Vera Miller, and together they had one child, Betty, born the following year. In the offseason, Kremer occasionally played in winter leagues and also worked as a laborer in the Oakland shipyards and oilfields.

After recuperating at home in Oakland, Kremer signed with Del Howard, manager of the Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League, in 1917. For the next seven years (1917-23), the 6-foot-1, 190-pound Kremer was the workhorse for the Oaks, one of the league’s weakest teams. (It enjoyed just one winning season during Kremer’s tenure.) At the time, the PCL played about 200 games during its six-month season (except in the war-shortened season of 1918) and was considered a pitcher’s league given the warm weather and conditions.

After two nondescript seasons (9-15 and 5-14), Kremer averaged 325 innings, 17.8 wins, and 18.6 losses over the next five years. But because of his failure with the Giants and Rochester and his health issues (rheumatism), contrasted with his new-found durability in the PCL, Kremer acquired a reputation as a “warm-weather” pitcher which deterred major-league teams from offering him a chance in spring training. After the 1922 season, when Kremer won 20 games for the first time in his professional career (he lost 18) and logged 356 innings, it appeared as though he would sign with the New York Yankees, but the Yankees and Oaks were unable to agree on a sale price.

At the age of 30 and in his tenth year of professional baseball, Kremer enjoyed his best season, winning a league-high 25 games and ranking second with 357 innings for the seventh-place Oaks. Praised by the Los Angeles Times as the “best right-hander in the Coast League,” Kremer was suddenly a hot commodity.6 “[I] thought I was doomed to stay in the minors forever,” he said. “I won and won. Scouts came and went. Then when I had given up hope of another major trial, there came old Joe Devine, a fellow I had known all my life.”7 Joe Devine, a longtime scout for the Yankees and Pirates and perhaps best known for signing Joe DiMaggio, encouraged Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss to sign Kremer when it appeared that the Chicago Cubs had a deal wrapped up. On December 13, 1923, a blockbuster deal was announced: The Pirates sent pitchers George Boehler and Earl Kuntz, infielder Spencer Andrews, and a reported $20,000 to the Oaks in exchange for Kremer.8

Kremer’s transfer to the Pirates did not go smoothly. Arguing that he was entitled to a share of his sale price, he refused to report to spring training; Oakland steadfastly rejected his demands. Eventually Dreyfuss intervened and reached a “compromise” with Kremer after which Kremer joined the team at spring training in Paso Robles, California, in late March.9 Manager Bill McKechnie was roundly criticized for adding a 31-year-old pitcher (who looked even older) to his starting rotation.

In a seamless transition to the big leagues, Kremer began his career by pitching five consecutive complete games. Joining a Pirates staff led by Wilbur Cooper, he debuted on April 18 at Redland Field in Cincinnati, where he gave up two runs in the bottom of the ninth to lose, 3-2. He followed the loss with four consecutive wins, including two shutouts. The latter was one of his two career two-hitters, a dominating 2-0 victory over the Chicago Cubs at Forbes Field that took just 1:20 to play. With 30 starts among his league-high 41 appearances, Kremer was durable, capable of starting on short rest and being called on for intermittent relief outings. He had winning streaks of six and five games, but won only once after August 23, and struggled in September when the Pirates overcame an 11½-game deficit to come within one game of the pennant-winning Giants. Along with teammate and fellow rookie Emil Yde (16-3), Kremer was praised as a “life-saver” by The Sporting News.10 He finished with 18 wins and 259? innings pitched (both fifth best in the league), and tied for the league lead with four shutouts for the third-place Pirates. As of 2013 the 18 wins were still a Pirates record for rookies.

Kremer was primarily a fastball pitcher with an “excellent change of pace,” a sharp breaking curve, and occasionally a screwball.11 Not overpowering like Dazzy Vance or Pat Malone, Kremer used his fastball to set up his other pitches. And he could throw all of his pitches from an overhand, side-arm, or even submarine delivery. Pirates beat reporter Lee Wollen noted, “There is nothing mysterious about [Kremer’s] delivery but the velocity of the ball at different angles makes it difficult for the batsman.”12 Kremer said his sidearm delivery was his “greatest help . . . in times of trouble.”13

A psychological student of the art of pitching, Kremer adjusted as he grew older and gradually lost his speed. At the age of 37 in his seventh big-league season, 1930, he led the NL in wins and innings on the strength of excellent control, arguably the league’s best changeup, and transforming into a low-ball pitcher. “I understand better how to pitch than when I had more stuff,” he told Baseball Magazine. “I have … a clearer understanding how to handle opposing batters, a confidence in what I can do, and recognition of the limits of my ability.”14 Suggesting speed was an overrated asset, Kremer believed his control was the key to his success.

Remarkably durable and healthy throughout his professional career, Kremer averaged 235 innings per season from 1924 through 1931 and won 15 or more games for seven consecutive seasons (1924-1930) for the Pirates. “I have never been bothered with a sore arm,” he said. “I have no doubt that one reason is that I always take care of my arm. Putting extra pressure on a pitcher’s arm is always dangerous.”15 Kremer said that to prolong his career, he rarely threw as hard as he could and adjusted his pitching style depending on how close the game was. A good fielder, Kremer also had one of the league’s best pickoff moves to first base and second base.

Off to a slow start in 1925, Kremer had an ERA over 7.00 four weeks into the season, and the Pirates trailed the Giants by a season-high nine games. But behind the league’s highest-scoring offense, the Pirates closed the gap in late June and secured their first pennant since 1909. A master handler of pitchers, Bill McKechnie employed an effective five-man rotation (Vic Aldridge, Kremer, Lee Meadows, Johnny Morrison, and Emil Yde), each of whom started at least 26 games, won at least 15, and pitched 207 innings or more. Concluding the season with an eight-game winning streak, Kremer posted a 17-8 record, made 27 starts among his 40 appearances, and completed 14 games.

Kremer’s pitching against the Washington Senators in the 1925 World Series cemented his place among the best big-game pitchers in Pirates history. After the teams split the first two games in Pittsburgh, Kremer went the distance in Game Three, in Washington, giving up four runs to lose 4-3. Pirates hopes were dashed the following day when Walter Johnson shut out the Corsairs on six hits, giving the Senators a commanding lead of three games to one. But the Pirates roared back. Aldridge pitched a complete-game victory in Game Five, then Kremer took the mound in Game Six in Pittsburgh and hurled a pressure-packed, complete-game six-hitter, winning, 3-2. In Game Seven, described by the Associated Press as “perhaps the most thrilling seen in World Series history,” a steady downpour of rain made conditions terrible.16 After the Senators battered two Pirates pitchers for six runs in four innings, Kremer took the mound in the top of the fifth inning with the Pirates trailing 6-2 against the Big Train. Kremer retired 12 of the 13 batters he faced (he surrendered a home run to Roger Peckinpaugh) while the Pirates stormed back, scoring six runs to win the game, 9-7, and give the Pirates their first championship since 1909. With his second consecutive victory, Kremer was hailed as the “Hero of the World Series.”17

With the acquisition of hitting phenom Paul Waner for 1926, the Pirates were expected to duplicate their success of the previous season. However, key players from the championship squad were beset by injuries (infielder Glenn Wright and outfielder Max Carey) or experienced down seasons (pitchers Vic Aldridge and Emil Yde), and the Pirates got off to a slow start. Kremer suffered from a sore right shoulder and made only two relief appearances in a month’s span from mid-May to mid-June, and had managed only ten starts three months into the season. But over the last nine weeks of the season, Kremer put together one of his best and most dominating stretches in his big-league career. He won 14 times, completed 13 of 16 starts, relieved four times, and notched a 2.18 earned-run average. It started on July 10 at Forbes Field, where Kremer tossed a complete game against the hapless Philadelphia Phillies to secure his seventh victory of the season, then followed with a four-hit shutout against the Giants. A convincing complete-game victory over Brooklyn on July 24 pushed the Pirates into a tie with the upstart Cincinnati Reds. Kremer pitched his second career two-hitter on August 30 against the Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park to keep to Pirates tied with the Reds, but Pittsburgh sputtered down the stretch, going 13-17 in September to finish in third place. In arguably his best season, Kremer tied for the NL lead with 20 wins (six losses), led the league with a .769 winning percentage and a stellar 2.61 ERA, and completed 18 of 26 starts among his 37 appearances. He finished third in the league’s MVP voting.

The Pirates had competed for the pennant in every year of the decade and 1927 was no different. They had a new manager, Donie Bush, and added another hitting sensation, 21-year-old outfielder Lloyd Waner, Paul’s brother. Named Opening Day starter for the first of three times in his career, Kremer hurled a six-hitter at Redland Field, defeating Cincinnati, 2-1. Just over a month into the season, he boasted a 6-2 record, but he was bothered by water on the knee. After resting for almost four weeks, Kremer returned, proved to be ineffective as a starter and reliever, then missed two more weeks in July.18 In almost a repeat performance from the previous year, Kremer was the NL’s most dominant pitcher over the last nine weeks of the season, completing 13 of 18 starts, winning 11 of 15 decisions, and posting a 2.03 ERA. He was at his best in September, when the Pirates needed him most. With Pittsburgh virtually tied with the Cubs, Kremer pitched eight complete-game victories in 23 days. His third shutout of the month, a three-hitter over Brooklyn at Forbes Field, was followed by his major-league record 22nd consecutive win at home, 5-2 over the Giants to maintain the Pirates’ three-game lead in the pennant race. Despite missing almost six weeks, Kremer was arguably the NL’s best pitcher for a second consecutive season. He won 19 games, completed 18 of 28 starts and posted the league’s best ERA (2.47) for the pennant-winning Pirates.

In the World Series the Pirates faced the offensive juggernaut of the New York Yankees, winners of 110 games and often considered the greatest team in baseball history. “Kremer is big, strong, and has a lot of stuff, as well as speed,” said Yankees manager Miller Huggins.19 Kremer started Game One, and was undone by two infield errors in the third inning that led to three runs. He was lifted after Tony Lazzeri belted a double to lead off the sixth inning with the Yankees leading, 5-3. Only two of the five runs scored against him were earned. The Pirates lost four straight to the Yankees and did not appear in the October Classic for another 33 years.

Though the Pirates led the National League in runs scored in 1928, the team’s pitching faltered, leading to a fourth-place finish. Burleigh Grimes, acquired in the offseason, paced the circuit with 25 wins, but Kremer, battling influenza for most of the first half of season, duplicated his annual Jekyll and Hyde act. A 4-11 start was tempered by a strong 11-2 finish with 11 complete games in 14 starts. He notched 15 wins in 28 decisions but his ERA almost doubled, to 4.64.

The Pirates’ offense clicked again in 1929, and a noticeably improved pitching staff had the team battling for first place for the first three months of the season. A traditionally slow starter, Kremer did not win his first start until five weeks into the season, then won 11 of his next 13 starts. On July 13 he tossed a complete-game victory against the Phillies to propel the Pirates to a season-high three-game lead over the Cubs. But in July the Pirates were beset by injuries to clubhouse leader Pie Traynor and spitballer Grimes (16-2 at the time), and played under .500 the rest of the way (36-39) while the Cubs continued to play well and cruised to their first pennant since 1918. Despite nagging knee pain, Kremer lead the runner-up Corsair staff with 18 wins.

At an age when many pitchers have lost their effectiveness, the 37-year-old Kremer led the NL in wins (20), starts (38), and innings (276?) in 1930, arguably the most stressful season ever on big-league pitchers. In the Year of the Hitter, the NL batted a composite .303 and averaged 5.68 runs per game; pitchers posted a combined 4.97 ERA. Kremer’s league-leading marks included a whopping 366 hits given up (a .322 batting average) and he surrendered 29 home runs, the most since 1884, and became the first 20-game winner to post an ERA above 5.00. Jewel Ens, who had replaced Bush during the Pirates late-season collapse the previous season, inherited an inexperienced and unusually weak pitching staff that was seventh in team ERA. Injuries to Lloyd Waner and Traynor resulted in the normally heavy-hitting team finishing sixth in batting. The team scored fewer runs than in 1929. For the first time since 1917, Pittsburgh finished the season in the second division (fifth).

Described by The Sporting News as intelligent and shrewd, Kremer no longer possessed a heater; rather, he succeeded by knowing batters’ weaknesses.20 For the first time in his big-league career, he was used exclusively as a starter in 1931, completing 15 of his 30 starts and logging at least 200 innings for the eighth straight season. Only Brooklyn’s Dazzy Vance and the Giants’ Clarence Mitchell, both 40 years old, were older starting pitchers in the NL, and neither started as many games as Kremer. But the big Frenchman suffered from poor run support as the Pirates offense continued to sputter, leading an Associated Press story to call Kremer the “hard-luck ace of the National loop.”21 Two of his losses were extra-inning affairs. He yielded a run to the Cubs in the tenth inning in a 4-3 loss in Pittsburgh, and pitched a career-high 11? innings at 4-3 loss to the Cardinals. In a career-high 15 losses, Kremer received three runs or fewer 14 times. With just 11 wins, his streak of seven consecutive seasons of at least 15 wins came to a close for the fifth-place Pirates, who finished with a losing record for the first time since 1917.

Like many prominent players of his era, Kremer’s career came to an ignominious conclusion. Used sparingly in 1932 by new Pirates manager George Gibson, he made just ten starts, most of them ineffective. Evoking memories of years gone by, Kremer tossed consecutive complete-game victories in mid-July, the former being one of his six career three-hitters and his 14th and final career shutout. Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss had a soft spot for Kremer, whose loyalty and heroics in the 1925 World Series brought the team back to national prominence. Despite rumors that Kremer would be waived in the offseason, the 40-year-old was brought back for his tenth big-league season in 1933. But sporting a 10.35 ERA in seven relief appearances, he was waived in July. He played briefly for his hometown Oakland Oaks in 1933 and 1934 before announcing his retirement.

In a 21-year professional career (1914-1934) Kremer logged 4,383 innings (1954? of those in his ten years with the Pirates) and won 258 games. His 143 victories in a Pirates uniform rank seventh in club history as of 2013.

In his post-baseball days, Kremer returned with his wife, Beulah, and daughter, Betty, to his beloved Oakland. Thousands of miles away from the closest big-league team and decades before westward expansion, Kremer gradually faded from minds and memories of baseball fans. Once thought to be possible coaching material, he drifted away from baseball and began a career as a postal carrier in Berkeley and the Bay area, where he worked for more than two decades. In the late 1950s he and his wife retired to Pinole, about 15 miles north of Oakland. Suffering from heart problems later in life, Kremer died on February 8, 1965, at the age of 71. He was buried at Sunset View Cemetery in El Cerrito, California.

Sources

Newspapers

Oakland Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Online sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Other

Ray Kremer player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 Dan Thomas, “May Settle Sand-Lot Baseball Feud When Pitchers Meet in Series Game,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, September 29, 1925, 11.

2 L.B. Gross, “Diamond Flashes,” Oakland Tribune, May 1, 1914, 18.

3 “This and That in the Coast League. Talk,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 1, 1916, 1.

4 Ford Sawyer, “Ray Kremer Was Bound To Be A Big-League Star – And He Is,” Boston Daily Globe, September 16, 1924, 19A.

5 “This and That in the Coast League. Talk.”

6 “Ray Kremer Pitches Oakland to Win,” Los Angeles Times, July 1, 1923, I11.

7 Cullen Cain, “Ray Kremer’s Uphill Battle,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, February 23, 1926, 5.

8 “Kremer to Pirates in Big Player Deal,” New York Times, December 23, 1923, 26.

9 Eddie Murphy, “Ray Kremer Signs Contract with Pittsburgh Pirates,” Oakland Tribune, March 27, 1924, 20.

10 The Sporting News, September 25, 1924, 2.

11 Bill Evans, “Pirate Pitchers Best Senators,” Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner, October 4, 1925, 11

12 Lee Wollen, “Ray Kremer Hopes to Better Last Year’s Record,” Pittsburgh Press, March 28, 1925, 12.

13 Cain.

14 Ray Kremer, “Pitching from a Veteran’s View Point,” Baseball Magazine, June, 1932, 347.

15 “Pitching from a Veteran’s View Point.”

16 “Pittsburgh Defeats Washington, 9-7, to Win World’s Baseball Championship” Associated Press, Berkeley (California) Daily Gazette, October 15, 1925, 1.

17 Eddie Murphy, “Hero of World Series Returns Home,” Oakland Tribune, November 5, 1925, 21.

18 “Ray Kremer Out of Line-up for 2 Weeks,” Oakland Tribune, May 18, 1927, 16.

19 “Kremer Held in Respect by Yankees Sluggers” Associated Press, Oakland Tribune, September 29, 1927, 26.

20 The Sporting News, April 9, 1931, 5.

21 Hugh Fullerton (Associated Press), “Rate Ray Kremer as Hard Luck Ace of the National Loop,” Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), July 23,1931, 5.

Full Name

Remy Peter Kremer

Born

March 23, 1893 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

February 8, 1965 at Pinole, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.