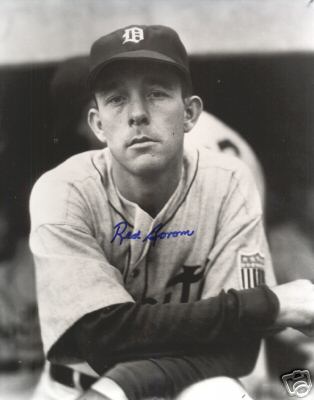

Red Borom

Most of the former ballplayers we read about were well known, or at least regulars, on their respective big league clubs. But since ball clubs usually have 25-man rosters, the majority of players were neither stars nor regulars. Instead, they played backup roles, riding the bench and waiting for their turn while the starters played the game.

Most of the former ballplayers we read about were well known, or at least regulars, on their respective big league clubs. But since ball clubs usually have 25-man rosters, the majority of players were neither stars nor regulars. Instead, they played backup roles, riding the bench and waiting for their turn while the starters played the game.

However, often the backup players are almost as good as the regulars. In any event, due to injuries, hitting slumps, pitching woes, and managerial strategies, the best teams are often the ball clubs that have good second-line players who are ready to step on the diamond and play regularly, if only for a short time.

When you study the history of baseball, you learn that in order to succeed and become a regular, a player has to have the right combination of abilities as well as be in the right place at the right time on the right team with the right manager. In other words, the success of a player’s career can depend as much upon timing as upon talent.

Edward J. “Red” Borom is a classic example of the young men who came of age during the Great Depression in the 1930s dreaming about playing major league baseball. However, it was tough to make a professional team, let alone the big leagues.

After a summer of semipro ball in 1934, Red struggled for years to move up the ladder of professional baseball. In 1944 he won a brief shot in the “Big Show”. In 1945 he played in 55 games for Detroit, hitting .269. The Tigers won the American League pennant over the Washington Senators, and went on to win the World Series in seven games over the Chicago Cubs.

Borom did not play a major role in the fall classic. Instead, since managers usually go with time-tested regulars in the World Series, Red rode the bench. However, he did get into game one. With one out, the bases empty, and the Tigers trailing 9-0 in the bottom of the ninth inning, Red pinch-hit and grounded out for pitcher Les Mueller.

“I hit a ground ball up the middle, off the glove of pitcher Hank Borowy,” Borom recalled. “The shortstop, Roy Hughes, threw me out on an extremely close play. I thought I had a base hit.”

Red also pinch-ran for catcher Bob Swift in game three, another Detroit loss. Borom did not get to play in any of the Tiger victories. But, Borom was a member of the World Series Champion Detroit Tigers, and the Texan owns a World Series ring to prove it.

In 1946, with veteran players returning from military service in World War II, Borom failed to make Detroit’s roster. “I’m grateful for the chance to have played on a World Series winner, but I was disappointed that I didn’t get a chance to be with the team the next season.”

Undaunted, Red played five more years of minor league ball. When his pro career was over, he played several seasons of semipro ball–ending his career at the same level where he began in 1934.

Borom’s baseball career differed from those of most ballplayers, because he played for several championship teams–including the Tigers in 1945.

“I’ve often been asked what was my biggest thrill in baseball,” Red explained in a 1997 interview. “I always reply that it was when Hank Greenberg hit the bases-loaded home run against the Browns [in September 1945] and we were behind 3-2 at the time. I was the runner on third, and when I saw the ball headed for the seats and knew we were in the World Series. Nothing could surpass that.”

In the end, Borom, a smooth fielding, left-handed batting shortstop-second baseman, compiled a respectable lifetime minor league average of .270 for 1,076 games, not counting playoffs. He also hit .250 in 62 games in the big leagues.

In addition, the redhead spent years playing semipro ball. The hustling infielder helped his Boeing Aircraft team win a national semipro championship in 1942 and his Sinton, Texas, club win a national semipro title in 1951.

Born on October 30, 1915, in Spartanburg, South Carolina, the son of Edward K. and Mary Borom, Red grew up in Atlanta. He attended Boys High (renamed Henry Grady High in 1947) and played baseball every chance he got. In his senior year, the school’s team included pitcher Jim Bagby, while Tech High had shortstop Marty Marion and pitcher Hugh Casey. All three later became big league players.

By the time Red graduated from high school in 1934, the Great Depression gripped the nation. Despite offers of two college baseball scholarships, the 18-year-old knew he needed a job.

“That summer I played semipro ball in Atlanta,” he recollected. “A teammate had a friend who owned the Jackson, Mississippi, class C team, and I was asked to report for their spring training in 1935.

“Thereby was the start of a real weird season. I was released on opening day of 1935, borrowed a dollar from my roommate, and caught a ride to Meridian, Mississippi, where I’d heard there was a good semipro team sponsored by a cotton broker, John Moss. They had guys like Eric McNair and Pap Williams. I made the team. They paid me $50 a month, and room and board was $20 a month. I stayed there until July, when I received a 1:30 a.m. call from Atlanta. When the landlady woke me, I was afraid someone at home was sick.

“Instead, it was Lee Head, manager of Knoxville in the class A Southern Association. He said a scout recommended me and he wanted to know if I would join the team the next day in New Orleans. I made it to New Orleans. We played seven games in four days, and I went 3-for-4 in the first game. Then the team traveled to Birmingham. After that series, I was released. They’d only signed me to fill in for an injured player.

“So I went home. At that time, Little Rock of the Southern Association was in Atlanta. I talked to Doc Prothro, the manager, and I worked out with them for two days. They signed me for the 1936 season.

“Two days later I got a call from manager Dutch Hoffman of Tallahassee in the class D Georgia-Florida League. They played a split season and the club was trying to win the second half. I told Hoffman I’d signed for 1936, and he assured me they’d release me after the season.”

Tallahassee finished in first place with a 69-50 record. Borom played the last month of the season, so his statistics are incomplete. But in the playoffs, the Capitols beat the Albany Travelers in seven games to win the title.

Red recounted, “Well, we won the championship, I hit the only homer in the playoffs, and they didn’t want to release me. I had to go to Judge Bramham, head of the minor leagues, and he ruled I belonged to Little Rock.”

Borom went to spring training with Little Rock in 1936. Within two weeks he was farmed out to Cleveland, Mississippi, in the Cotton States League. There the 5’11” 180-pound spray-hitting shortstop batted .255 in 127 games. Cleveland finished in seventh place with a 57-80 record, and Red’s odyssey continued.

“I want to add a happening that players today won’t believe. We played a Saturday night double-header in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. The first game started at six o’clock and went twelve innings.

The second game started at 9:45 and was a wild one, something like 11-10. We left the ballpark at 1:40 a.m. to hop in the bus and ride 100 miles to Helena to ferry the Mississippi River.

We missed the ferry by about ten minutes and had to wait an hour for it to return. We crossed into Clarksdale, Mississippi, and still had fifty miles to go to Cleveland.

“We got there at 9 a.m., hung up the wet uniforms in the basement of the high school, ate breakfast at the boarding house, went back to the school to put the wet uniforms on, and got on the bus to go fifty miles for a double-header. Every Sunday was a double-header, 140 games in 120 days.

“We never stayed overnight in Greenwood. So instead of getting the usual $1.25 per day for meal money, when we got back home we were given fifty cents. We’d been going from 4 p.m. the previous day until 9 p.m. when we got back to Cleveland!

“I had what I thought was a good season for my first full year, but two months later I was released. I was beginning to wonder if I would ever make it, but I decided to keep trying.

In 1937 I went to spring training with Macon in the class B Sally [South Atlantic] League. In those days each club could carry so many veterans, class men [players with less than three years experience], and rookies. I all but had the team made, but because of five rained-out games in the ’35 playoffs with Tallahassee, I was a ‘class man’ and was released.

“So I went back to the Cotton States League with Clarksdale, stayed there for a month, and was sold to Monroe, Louisiana, in the same league. After a month there the owner wanted me to take a cut in pay, or he’d release me.

“I opted for my release and caught on with Meridian, where I’d played semipro in 1935. I finished the season there in the class B Southeastern League, and so help me, in the off-season I was released.”

Borom produced a good season in 1937, hitting .279 for Meridian. But the Scrappers finished fifth out of six teams with a 58-78 mark, and the ball club dropped him.

“In 1938 I was at Montgomery of the Southeastern League, and in mid-season I was traded to Greenville, South Carolina, of the Sally League. After a month there I received a telegram from Judge Bramham saying the deal was called off on a technicality.

“I finished the season with Montgomery and reported back to that club in 1939. Then in spring training, I had the only injury I ever had in baseball, a pulled hamstring. By the time I recovered, the club’s lineup was set, so I asked for my release.”

Red played well in 1938, hitting .277 for class C Montgomery. But the Bombers finished last (60-88) in an eight-team league, and again he was expendable. “I’d decided life in the bush leagues was not for me. But two days later a friend, Rosy Gilhousen, who was managing Tallassee in the class D Alabama-Florida League, asked me to play for him. I told him I would if he’d predate my release, because this was my last year. We won the league championship, and I went home to Texas, where my family had moved.”

As it happened, Borom played his best minor league ball for Tallassee, Alabama, in 1939, hitting .327 in 93 games. He also played on his second championship team, helping Tallassee beat Andalusia in seven games of the Shaughnessy Playoffs.

In 1940 Borom signed and played one month for Tyler in the class C East Texas League. But by prior agreement, he switched to the semipro club in Mount Pleasant, Texas, where he earned $150 a month during the season. He could not earn that much by playing minor league ball.

“We went to Wichita, Kansas, in August to play in the national semipro tournament. We finished second. While there I was offered a job with Stearman Aircraft (later Boeing) to play ball. I earned $90 a month, and it was a year-around job.

“My family moved to Wichita and we lived there for six years, prior to moving to Dallas in 1946. In ’42 we won the semipro championship at Boeing.”

In the meanwhile, Boeing Aircraft became part of America’s huge military buildup during World War II. The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, catapulting the U.S. into war.

“In January 1943 I was drafted and taken into the Army at Fort Riley, Kansas. The commandant there was a real baseball fan, and we had several major league players, outfielder Pete Reiser, pitcher Ken Heintzelman, and infielder George Archie.

“The following January I was transferred to Camp Robinson, Arkansas, and in March I was discharged because of migraine headaches. I went back to Wichita and planned to work and play ball for Boeing.

“I’d had enough of being shuffled around in the minors.

“Two days after getting home, I got a call from Jack Zeller, general manager of Detroit. Unknown to me, Red Phillips, a teammate at Boeing and an ex-Detroit pitcher, had called Zeller to recommend Chuck Hostetler and me.

“Four days after getting out of the service, I was in training camp with Detroit in Evansville, Indiana. I realized it was wartime, but there were some good players still in the majors. I enjoyed playing in such improved conditions. The ballparks were better than any of the minor league places I’d played.”

Red played in seven games for the Tigers in 1944, but he hit only .071. Most of the year he spent with Detroit’s top farm club, the Buffalo Bisons of the International League. At Buffalo, Borom averaged .217 but fielded well. Buffalo finished in fourth place with a 78-76 ledger.

In 1945 he played most of the season with Detroit, making his biggest contribution in September. Subbing for injured second baseman Eddie Mayo, Red batted over .300 during the September pennant drive. For the season, he hit .269, cracking four doubles and collecting nine RBIs.

But Borom was disappointed when he had no real chance to make the Tigers in 1946. But he was not alone. For example, Tiger right-hander Les Mueller, who produced a 6-8 record with a 3.68 ERA and who also owned a 1945 World Series ring, was optioned out on opening day of 1946.

Detroit also sent catcher Harvey Riebe, who hit .314 as a rookie for the Tigers in 1942 before spending three years in the Army, to Dallas. Like Borom, who batted .278 for Dallas, Riebe enjoyed a solid season (.242 BA, 4 HR, 32 RBI) and helped the Rebels win the Texas League Title.

With big hitters like Clint Conatser (.280 BA, 13 HR, 70 RBI), Dallas defeated the Atlanta Crackers in four straight games-winning the first two in Atlanta, 13-3 and 3-0.

RED BOROM SPARKS DALLAS TO VICTORY declared the caption on the newspaper story in Borom’s hometown when the Rebels won game three, 5-1. The redhead beat out a bunt in the eighth inning and later scored the first run, igniting a five-run Dallas rally that brought the club back from a 1-0 deficit to win. But in the fourth and final game of the playoffs, Borom, playing shortstop, went hitless.

“‘Red was a steady player and a good fielder who helped in lots of ways,’ Harv Riebe recalled. ‘He played several positions. He really helped the ball club, and I remember him well.’”

Talking about his stint with Dallas in 1947, Borom said, “I was relegated to utility duty. Detroit sent Johnny Lipon here and wanted him to play shortstop. I could understand that, because Lipon was ten years younger. Even at that we both made the All-Star team selected to play Houston, the league leader as of July 4th.

“In the All-Star game I played half the game at second base and hit a double to drive in two runs that won it.

“At the start of the ’48 season, I was with Dallas for a month when I was asked to manage a farm team, Texarkana in the class B Big State League. I wound up the season playing with Paris, Texas, in the same league.”

Reflecting on his travels in 1948, Red recollected, “As for going from managing at Texarkana to playing with Paris, it is quite a story! Dick Burnett, who owned the Dallas ball club at the start of the ’48 season, also owned the Texarkana club in the Class B Big State League. He asked me to take over as manager of Texarkana. This is the same fellow that bought my contract from Helena, Arkansas, in 1937 in the Cotton States League. About mid-season, Burnett asked me to take a cut in pay or else he would have to release me. So I told him to give me my release, and I joined Meridian in the Class B Southeastern League. After being at Texarkana for about two months, Burnett sold his interest in the club to his oil partner and wanted me to return to Dallas, and I did. A week later, we were in Shreveport. Just as I was getting out of bed around seven o’clock in the morning, I got a call from Homer Peel, who managed Paris, in the Big State League. Homer told me that he had just swapped Frank Carswell to Dallas and got me in the trade. In fact, that was the second time since I had returned to Dallas that I had received notice of being traded; the first being to Oklahoma City in the Texas League, but I couldn’t get together with the owner of Oklahoma City on contract terms. Neither time had Burnett given me any notice that he was trading me! So I told Burnett in no uncertain terms what I thought about his actions, and I left Shreveport and went back to Dallas. Eventually, Homer Peel and I worked out a deal, and I finished out the season playing for Paris.”

At Texarkana, Borom replaced Vern Washington, who was fired. But after refusing to take the pay cut demanded by the team’s owner, Borom spent a month with Dallas, hitting .252 with 10 RBI. But thanks to Homer Peel’s offer, Red returned to the class B Big State League and played the second half of the season with Paris. Still swinging a good bat, the journeyman infielder averaged a combined .304 for Texarkana and Paris in 1948. When the season was over, Paris had finished in seventh place, one notch above Red’s first club, last-place Texarkana.

Continuing his travels, Red explained, “In ’49 I managed Baton Rouge in the class C Evangeline League in the last half of the season. I thought that was the end of my career, and I went to work for the postal service for a while in 1950. But at mid-season, Bobby Bragan, manager of Fort Worth in the Texas League, asked me to join the team as a player-coach, which I did.”

Borom recollected how money affected players during the season and the offseason in his day: “As to my going to Fort Worth in the middle of the season in 1950, at the time I was employed at the Dallas Post Office, and I took a leave of absence to play for Bobby Bragan and Fort Worth. That was my last season in pro ball, and I hit .278, mostly as a pinch-hitter.

“In those days, even major league players weren’t making the kind of money they do nowadays, and when you came home, you immediately went out looking for an offseason job. I worked several different places in Dallas, my hometown, including one year as a deputy sheriff. To give you a good example of what it was like in the major leagues in the 1930s, Luke Appling, after his first year with the White Sox, came home to Atlanta, where I grew up. Luke and my brother James worked at a local men’s clothing store for $12.50 per week!

“But returning to my story, the next year, 1951, I moved to Sinton, Texas. There I played semipro ball for the Plymouth Oil Company for three years. We had a good team with former big leaguers like Tom McBride and Roy Easterwood. In 1951 we won the semipro tournament in Wichita in seven straight games. My final year was with the Victoria, Texas, semipro team in 1954.

“So with all the bumps in the road, I managed to play on some championship teams, starting in 1930 with my junior high team, which won the Atlanta City Championship. I still have the little gold-plated baseball given to us for that team.”

These are the major highlights that Borom recalls:

* Tallahassee, FL, 1935 Champions of Georgia-Florida League

* Tallassee, AL, 1939 Champions of Alabama-Florida League

* Boeing 1942 Champions of national semipro tournament

* Detroit 1945 World Series Champions

* Dallas, TX, 1946 Dixie World Series Champions

* Plymouth Oil 1951 Champions of national semipro tournament

Reflecting on those teams and the six titles, Red observed, “I guess a career that looked like it was headed nowhere for so long turned out pretty well.”

In fact, Borom, who traveled with more minor league teams than most players ever hear about, was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame in 1978 and the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame in 1996.

In 1947, before his second season with the Rebels, the infielder started planning for his life beyond baseball when he and a friend opened Red Borom’s Steak House in Dallas. They ran the restaurant for almost four years, but it was a time-consuming business, and the partners sold it in 1950. Red started that year working for the U.S. Postal Service in Dallas, but he left that position to coach and play for Bobby Bragan at Fort Worth. After the 1950 season, he moved to Sinton and worked three years for Plymouth Oil. When he quit playing for the Sinton semipro club at the end of the 1954 season, Red moved back to Dallas. There he found a position in the sales end of the trucking business, and he worked for East Texas Motor Freight for 18 years. Later, he switched to the Grave’s Truck Line, also in Dallas, before retiring in 1980.

During those years Red always kept in touch with baseball, and he always answered the letters and requests for autographs from fans of “old-time” baseball. He and Harvey Riebe were among the former Tigers that Detroit invited to the final game at Tiger Stadium in 1999.

The Texan has many good memories. For example, while attending a Chicago Cubs Old-Timers game in 1980 (all players from the 1945 World Series were invited), Red learned from the program that he was the only player in the American League to have five hits in a game twice during the 1945 season.

“I went 5-for-5 against the Indians and I went 5-for-6 against the Yankees,” Red recalled. “On the third time up against New York, I dropped down a short bunt. It was a close play at first, but the umpire called me out. The next time up I singled. When I rounded first and came back, Nick Etten, the Yankee first baseman, told me I beat out that bunt. If I were safe, I’d have gone 6-for-6 in a nine-inning game. Ty Cobb set that major league record in 1925. Damion Easley tied it a couple of years ago. All three of us played for Detroit.

“As insignificant as that 5-for-5 may sound,” Borom said, “it was something I never dreamed about during all those trying times in the minor leagues.”

Now retired, the redhead, a bachelor, still lives in Dallas. He still answers fan mail, much of it from Tiger fans who remember the 1940s.

Red Borom’s long baseball career illustrates the kind of talented, hard-working, dedicated players who kept pursuing the elusive baseball dream–even though it often meant starting over again and again with new teammates on mostly minor league ball clubs–when the game was still considered the National Pastime.

Sources

This essay about Red Borom’s baseball career is based on statistics from The Baseball Encyclopedia (Macmillan, 8th edition, 1990); minor league stats from profile furnished by Pat Doyle, creator of the Professional Baseball Player Database (version 5); clippings from the Borom file in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Library; interviews with Red Borom in July and August, 1997; letters from Borom dated July 14, 31, August 27, October 10, November 21, December 1, 2, 13, 30, 1997, and January 17, February 4, March 9, 20, April 7, 15, May 15, 19, June 8, 18, 26, July 13, 24, August 5, 15, December 2, 31, 1998, and January 27, June 16, July 1, November 2, 1999; and clippings about Detroit games as well as minor league games from Borom’s scrapbooks.

Full Name

Edward Jones Borom

Born

October 30, 1915 at Spartanburg, SC (USA)

Died

January 7, 2011 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.