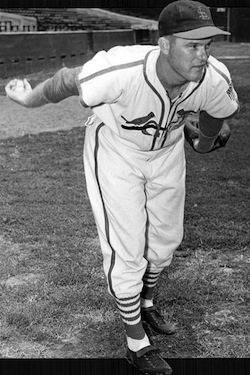

Red Munger

Known for his big wad of chewing tobacco, Red Munger was a hard-throwing Texan with a mean fastball and a knee-buckling curveball. After paying his dues for six years in the St. Cardinals’ deep farm system, Red debuted in 1943 for the world champions. Before entering the US Army in mid-1944, he was arguably the best pitcher in baseball with an 11-3 record and a 1.34 earned-run average. Though he did not live up to the promise that season suggested, Munger was named to three National League All-Star squads, hurled a complete-game victory in his only World Series appearance, in 1946, and notched 77 wins in his ten-year major-league career.

Known for his big wad of chewing tobacco, Red Munger was a hard-throwing Texan with a mean fastball and a knee-buckling curveball. After paying his dues for six years in the St. Cardinals’ deep farm system, Red debuted in 1943 for the world champions. Before entering the US Army in mid-1944, he was arguably the best pitcher in baseball with an 11-3 record and a 1.34 earned-run average. Though he did not live up to the promise that season suggested, Munger was named to three National League All-Star squads, hurled a complete-game victory in his only World Series appearance, in 1946, and notched 77 wins in his ten-year major-league career.

George David Munger was born on October 4, 1918, the first child of Collie (C.B.) and Bessie Mae Munger in Houston, Texas. Like their parents, C.B. and Bessie Mae were both born in Texas; they married in 1917 at the young ages of 19 and 15 respectively. The Mungers lived in the eastern part of downtown Houston, the historical center of the fast-growing and industrializing city. C.B. worked as an automobile painter and Bessie Mae was a homemaker. When George was 17 years old, his parents started a “second” family and welcomed three more children: Ross, Delores, and Clayton. George was a strong, husky youngster with a shock of thick red hair, hence his nickname. Growing up, Red was a big fan of the Houston Buffaloes, whose games he attended in the team’s then state-of-the art Buffalo Stadium, which opened in 1928. By all accounts he played baseball every chance he could, especially in the city’s competitive sandlot leagues. A standout basketball and baseball player at Sam Houston High School, Red established his reputation as one the area’s hardest-throwing right-hand pitchers and a dangerous slugger. In 1937 Fred Ankenman, the president of the Buffaloes, an affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals, signed the 18-year-old Munger to a contract. Ankenman praised Munger as “the finest young player in Houston’s amateur circles last summer.”1

Munger pitched twice for the Buffaloes, giving up three earned runs in 11 innings, then was optioned to the New Iberia (Louisiana) Cardinals in the Class D Evangeline League, where he could start regularly. Leading the league in wins (19), innings pitched (284), and appearances (47), Munger made headlines in the Cardinals organization as the next young pitching phenom. Invited back to the Buffaloes spring training in 1938, he was given a good chance of securing a spot in their talented rotation. “[Red has] a good fastball,” said manager Ira Smith. “He should help tremendously [and] should be a major leaguer within two years.”2 On a staff boasting future big leaguers Harry Brecheen, Mort Cooper, Johnny Grodzicki, and Ted Wilks, Red pitched in 14 games (nine starts), but won just two of seven decisions with a 3.97 ERA before sent to New Iberia once again. In a half-season there, he won ten games and his 2.47 ERA was fourth best in the league. Coinciding with his second year in Organized Baseball was his marriage to 20-year-old Virginia Jo Donovan of Houston.

Along with three other young pitching prospects (Howie Pollett, Ernie White, and Red Barrett), Munger was invited to the Buffaloes’ spring training for the third year in a row. “It’s asking a lot to develop four regulars out of our youngsters,” said the new Buffaloes’ manager, Eddie Dyer, whose staff was already arguably the deepest in all of Organized Baseball.3 After spring training Red was sent to the Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists in the Class B Piedmont League. The youngest pitcher on the staff, the 20-year-old led the team in wins (16), innings pitched (236), and appearances (46) and helped the Tourists to their second league championship in three years.

Promoted to the Sacramento Solons, the Cardinals’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, for the 1940 season, Munger struggled for the first time in his baseball career, lost his position in the starting rotation, and finished with a losing record (9-14). The next season, still only 22 and the youngest starting pitcher on the team, Red responded to new player-manager Pepper Martin’s aggressive, fast-paced style of baseball. The Solons led the PCL for most of the season before a late-season fade dropped them to second place with a 102-75 record. With 159 strikeouts (third best in the league), Munger was considered one the hardest throwers, but was also a hard-luck loser, posting a 17-16 record and a 3.07 ERA in 261 innings, including 31 starts and 15 relief appearances. After a two-hit shutout against eventual champion Seattle in Game Four of the league playoff finals, he was added to the Cardinals’ roster.

Participating in his first major-league spring training in 1942, Munger was a proven workhorse, having averaged 236 innings during his first five seasons in the Cardinals organization. “Munger bears watching,” said The Sporting News; however, Cardinals manager Billy Southworth confessed his difficulty in paring the staff down to nine or ten pitchers. Munger was optioned to Columbus (Ohio) in the American Association, where he was reunited with Eddie Dyer in his first year at the helm of the Red Birds. Led by all-stars Brecheen (19-10 and a 2.09 ERA) and Munger (16-13, 3.52; he also batted .301), the Red Birds finished a disappointing third in the league, but saved their best for the playoffs. Munger tossed a three-hit complete game to beat the Toledo Mud Hens 6-1 and conclude a four-game sweep for the Governor’s Cup. Labeled the “ace of the Columbus staff,” Munger hurled a complete game to defeat the Syracuse Bears of the International League in Game Three of the Junior World Series title, which Columbus won in five games.4 Asked about his pitching influences, Munger said that he patterned his game after the Cincinnati Reds’ big pitcher Paul Derringer, “He was my hero and role model right from the start of my career,” Red said. “I liked his style of rearing back and throwing hard.”5

Because of wartime travel restrictions, the reigning World Series champion Cardinals opened their 1943 spring training in Cairo, Illinois, about 150 miles southeast of St. Louis. Munger contracted a severe case of chicken pox, which hampered his conditioning and pitching, and his status on the team was in doubt until the end of camp. But Southworth kept him, and he made his major-league debut on May 1, relieving Harry Gumbert with two outs in the eighth inning against the Cincinnati Reds. Munger surrendered three hits and two runs (one earned) in an unspectacular debut. Pitching out of the bullpen during the Cardinals’ battle with the Dodgers for first place in May, June, and most of July, he was given a spot start due on July 21 because Ernie White and Gumbert were injured and tossed a complete game, defeating the New York Giants, 3-1, to give the Cardinals a 4½-game lead over Brooklyn. Four days later he pitched again and hurled another complete game to beat the Boston Braves, 7-3. In his next start, against the Philadelphia Phillies on three days’ rest, he last just one-third of an inning and gave up four runs. Southworth gave him a shot to redeem himself the next day. The big right-hander (6-feet-2 and 210 pounds) pitched another complete game, surrendering 13 hits and five runs (three earned) in a 13-5 walloping of Philadelphia. Going 68-25 to conclude the season, the Cardinals easily won the pennant with a pitching staff that paced the league with a 2.57 ERA. In nine starts and 32 appearances (93? innings), Munger won nine of 14 decisions and posted a 3.95 ERA. In the World Series rematch against the New York Yankees, the Cardinals lost in five games and Munger did not pitch.

In the wake of the Cardinals’ loss of Murry Dickson, Howie Krist, Pollett, and White to the US military to start the 1944 season, rumors swirled that Munger would be the next Cardinals pitcher to go. After two wins in relief (the latter a 7?-inning effort in which he surrendered just one hit to the Cubs in a 5-4 victory at Wrigley Field), Munger commenced the best stretch of pitching in his professional career by tossing a four-hitter over 7? innings in a no-decision against the Reds on April 27. He threw his first big-league shutout on May 14 by blanking the second-place Phillies on six hits in a 1-0 victory to give the Cardinals a 3½-game lead in the pennant race. Four days later he tossed a five-hit shutout over the Braves, striking out seven and walking just one at Sportsman’s Park, winning 2-0 and lowering his ERA to 0.61. But the Cardinals’ worst fears were confirmed when Munger was inducted into the Army at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis on May 23, though his muster date was not announced. With the Cardinals building their lead in June, Munger won five of six starts, pitched four complete games, and got saves (a statistic that did not then exist) in two of the three games he relieved in. Locked in a scoreless pitchers’ duel with the Phillies’ Bill Lee on June 29, Munger lost a heartbreaking 1-0 decision when he surrendered a run-scoring single to Jimmy Wasdell in the tenth inning. After learning that he had to report to Jefferson Barracks for active duty on July 12, Munger responded by tossing his seventh complete game in 12 starts and beating the Giants 4-1 on July 5 to raise his record to 11-2 and lower his league-leading ERA to 1.21. Named to the NL All-Star team, Red traveled to Houston after the victory to visit his parents before returning to St. Louis on July 7 and pitching 1? ineffective innings in relief against the Braves (and getting the loss) to finish with an 11-3 record and a microscopic 1.34 ERA. Having surrendered just 92 hits in 121 innings, Munger was the most difficult-to-hit pitcher in the league.

Mustered into service on July 12, the day of the All-Star game, Red donned the uniform of his camp team and beat the Lambert Field Navy Wings 2-1 in a seven-inning complete game on his first day in the Army. From Jefferson Barracks, Munger was sent to Camp Roberts in California, where he completed 17 weeks of basic training. He was then assigned to Fort Benning in Georgia, where he graduated from Officers Candidate School and was commissioned a second lieutenant on April 14, 1945.6 Assigned as an officer at the camp prison, Munger made a name as one of the Army’s greatest pitchers while playing for his post team, the Training Rifles Regiment. The Sporting News reported some of his legendary accomplishments, such as striking out 13 in his debut in May, striking out a record 16 batters on June 4, and surrendering just one earned run in his first 58? innings.7 “Pitching in every inning of every game,” and winning 13 of 15 decisions, Munger led his team to an Army league championship and became a local sports hero.8 “Munger gets credit for remarkable spectator interest in baseball at Fort Benning,” reported an Associated Press story about the major-league-like atmosphere and 8,500 fans at games when Munger pitched.9

World War II ended in August 1945 and the Cardinals anticipated that Munger would be discharged early enough to participate in 1946 spring training, but they were sorely disappointed when he was sent to Germany in 1946 as part of the American occupation force. The news that he would be going overseas came as a shock to Red, who had a wife and two young children expecting him back at home. “I spent my entire seven months in Germany and Heidelberg,” said Munger who was in charge of developing an athletic program for the Third Army.10

Discharged in August 1946, Munger joined the Cardinals on the tail end of an 18-game homestand during which they turned a 2½-game deficit into a 2½-game lead in the pennant race. Living in the Fairgrounds Hotel near Sportsman’s Park, Munger made his season debut in the second game of a doubleheader on August 25 against the archrival Dodgers. Despite walking two batters in the third of an inning he pitched, Munger was ecstatic, and so too were the Cards. “I am in splendid shape,” he said. “I was fast, my curve was good. But I had no control.”11The Sporting News reported, “Some … believe that Red will prove the deciding power in the battle with the Dodgers.”12

After an impressive first start in almost 14 months (five innings of five-hit, one-run ball against the Pirates on September 1), Munger pitched on short rest and tossed a complete game, beating the Cubs in St. Louis 8-1 on September 4. Striking out seven and issuing no walks, Munger extended the Cards’ lead to two games over the Dodgers. “I use a curve, fastball, and a change of pace,” he said of his pitching arsenal. In his next outing, on September 8, he pitched a career-high 11 innings in a complete-game victory over the Pirates, 5-4, at Sportsman’s Park. “I was glad to get that extra-inning game behind me,” said Munger, who now had pitched 25 innings in seven days. “It helped me to perfect my control and get the corners.”13 After being shelled by the Dodgers and not making it through the first inning in his next start, he surrendered just four earned runs in 16 innings in his next two starts (both no-decisions) to earn the most important start of his career. With a chance to clinch the pennant with a victory in the last game of the season if the Dodgers lost, Munger faltered against the Cubs, giving up six hits and three runs in 5? innings in an 8-3 loss, setting up a best-of-three playoff with Brooklyn to decide the pennant.

Defeating the Dodgers in the playoffs in two games, the Cardinals faced the Boston Red Sox in the World Series. With the Cardinals down two games to one, manager Dyer was roundly criticized when he selected Munger to start the pivotal Game Four, but Dyer never wavered in his support of the big redhead. In another career-defining game and supported by a then World Series record-tying 20 hits, Munger pitched a complete game to beat the Red Sox 12-3 on October 10 in Boston. “A brilliant game” reported The Sporting News.14 Munger surrendered nine hits, but yielded only one earned run in a commanding performance in the only World Series appearance of his career. Five days later, the Cardinals won Game Seven and their third World Series in five years.

In 1947, with his first spring training in three years, Red was expected to regain the form that made him one of the best pitchers in the big leagues in 1943. Considered one of the hardest throwers in baseball by slugger Ralph Kiner, Munger started the season with an impressive eight-hit, 4-1 victory in Cincinnati on April 16. Battling control problems (he surrendered a career-high nine walks on April 30), Munger blanked the Pirates on six hits, winning 2-0, on May 23 for the first of his six shutouts that season. With flashes of dominance, Munger tossed a pair of three-hitters, beating the Dodgers 3-0 at Sportsman’s Park on June 13 and crushing the Cubs 7-0 on July 4, improving his record to 7-1 and earning an invitation to the All-Star game. After not playing in the midsummer classic, Munger got off to a dreadful second half, surrendering 21 earned runs in 24 1/3 innings, prompting manager Dyer to express frustration about his consistency.

Munger’s three-hit shutout over the Pirates on August 8 brought the Cardinals within four games of the league-leading and eventual pennant-winning Dodgers. “We don’t even go over the batters with Munger,” said Dyer of Red’s preparation for games. “We just let him pitch.”15 Winning six of his last eight starts, including five complete games and his fourth three-hit shutout of the season, Munger concluded his best major-league season with career highs in victories (16, with five losses), innings pitched (224?), starts (31), and complete games (13). After the season he had surgery to remove his appendix and take bone chips from his right elbow. Both problems had bothered him since the All-Star Game.16

The Cardinals inaugurated a new era in 1948 when longtime owner Sam Breadon sold the club to St. Louis businessmen Robert Hannegan and Fred Saigh. After tossing a five-hit complete game to defeat the Reds 5-2 in his season debut on April 21, Munger battled control problems and inconsistency, losing seven of nine decisions in May and June. Dyer thought Munger was attempting to become a “spot pitcher” instead of just rearing back and firing; however, Munger was still bothered by elbow soreness and consequently was relying less on his fastball and hard curve, his two best pitches.17 While The Sporting News reported on the “crisis” of Munger’s arm, he was demoted to the bullpen in late June with the Cardinals in their annual pennant race.18 Pitching no better in relief and shelled in two spot starts in July, Munger had only a 4-7 record and dismal 5.99 ERA by the end of the month, prompting reports that he was “washed up.”19 But Dyer, whom players considered like a brother, never lost confidence in Red. Given a spot start on August 4, he hurled a complete game to defeat the Giants 7-2 in the Polo Grounds and fought his way back into the rotation. By tossing a complete game and relying on his “one-groove, three-quarters-motion fastball” to strike out a season-high seven and defeat the Pirates 7-2 on August 21, Munger pulled the Redbirds to within one game of the league-leading Boston Braves; but, that was the closest the Cards got as they went just 22-19 down the stretch to finish in second place for the second consecutive year. The 29-year-old Munger finished with a 10-11 record and an unsightly 4.50 ERA in 166 innings.

Off to a horrible start in 1949, Munger was 2-2 with a 7.89 ERA at the end of May, having failed to make it through the first inning in three of his last four starts. Preferring to throw his slider (which he characterized as “half curve, half fastball” which “takes off opposite to the direction of the curve”), Munger had poor control and lost his hard-throwing edge.20 “[I told] Munger that unless he started to cut loose and forget his operation, he wouldn’t win,” Dyer said.21 Pitching to maintain his spot in the rotation, Munger began to turn his season around in June, winning four of five decisions, including a four-hit shutout over the Braves on June 26 when the career .174 hitter (70-for-402) smashed his only major-league home run. With a 6-4 record and 5.07 ERA, Red was a surprise and controversial selection to the National League All-Star squad by former Cardinals and current Braves skipper Billy Southworth. Munger pitched a hitless fifth frame with one walk. Dyer considered Munger’s performance an unequivocal confidence-booster and the big redhead proceeded to pitch five consecutive complete-game victories to start the second half of the season. “Munger Stops Throwing ‘Junk Stuff’ and Starts Winning with Blazing Speed and Sharp Curve” reported Bob Broeg in The Sporting News.22

Discarding his ineffective changeup, Munger used his knuckleball (which he had thrown since 1943 but only recently began to control) as his primary off-speed pitch. In the heat of yet another pennant race with the Dodgers, Munger tossed arguably the best game of his big-league career on September 13 by blanking the Giants on one hit at Sportsman’s Park, winning 1-0 and giving the Cardinals a 1½-game lead over the Dodgers with just over two weeks left in the season. When he overpowered the Phillies with seven strikeouts in seven innings for his 15th and final victory of the season on September 18 helping increase the Cardinals’ lead to 2½ games, it appeared as though the team was on its way to the pennant. But the Cardinals were doomed by a 5-7 record down the stretch, including Munger’s last two starts (both losses during which he surrendered eight earned runs in 4? innings), and finished one game behind their archrival Dodgers. Though he finished with a 15-8 record and a 3.87 ERA, Munger’s poor pitching when the team needed it most contributed to a widespread criticism that he could not win the “big game.”23

During the offseason Munger lived with his wife and children in Houston. He often officiated high-school basketball games to stay in shape, participated regularly in exhibition baseball games, and was an avid golfer, hunter, and fisherman. With teammates and local residents Ted Wilks and Howie Pollett, Munger worked with Houston-area baseball players to foster and sponsor player development and remained close to the Buffaloes. In the mid-1950s, Munger sold insurance at Eddie Dyer’s agency.

With “great stuff” but inability to win consistently (just 11 wins in 1950 and 1951 combined), Munger was labeled an “enigmatic pitcher.”24 Jackie Robinson considered his pickoff move to second base the best in the league and umpire Scotty Robb said he had “the fastest ball and best curve in the National League,” yet Munger was beset by control problems and lapses in concentration that led to his demotion to the minor leagues during the 1952 season.25

After six losses in eight decisions and with the Cardinals in a tight pennant race in 1950, Munger lost his position in the starting rotation in mid-July. With the Cardinals out of contention in September, Munger pitched in a curious and controversial game on September 15 in Brooklyn. On his last pregame warm-up pitch, the scheduled starter, Cloyd Boyer, hurt his arm and was removed before he threw an official pitch. Munger entered the game and pitched all nine innings, giving up nine hits and two runs in a Cardinal victory. He was not credited with a complete game because he was not the officially announced starting pitcher. On September 30 Munger tossed his best game of the season and his 13th and final shutout in the big leagues by blanking the Cubs on four hits and striking out seven. He finished the season with a 7-8 record and a 3.90 ERA.

After the Cardinals’ fifth-place finish (their worst since 1938), owners Hannegan and Saigh replaced Eddie Dyer with Marty Marion and pledged a much tougher approach with an aging team. Rejecting a reported 20 percent pay cut from an annual salary below $20,000, Munger held out in 1951, causing tensions with management.26 Relegated to the bullpen to start the season, he never got on a track. Given a few spot starts but bothered by a back injury suffered in a fall at home, Munger had a 4-5 record and an ERA over 5.00 at the end of July. After the team physician, Dr. I.C. Middleman, removed an egg-sized cyst from the lumbar region of his back in August, Munger pitched only twice before being shelved for the season. In his last start on September 9, he went just 1? innings.27

The “problem man of the mound” began the 1952 season with his career in doubt.28 Cardinals beat reporter Bob Broeg wrote that the 33-year-old Munger “has lost his major league edge” and suggested that the team needed to move on without him.29 After surrendering seven hits and six runs in 4? innings in a crushing loss to the Cubs on April 19, Munger was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Bill Werle on May 3. Winless in three decisions and burdened by a 7.18 ERA with the Pirates, Munger was assigned in mid-June to the Hollywood Stars, the team’s affiliate in the Pacific Coast League.

Pitching for the Stars from 1952 through 1955, Munger attempted to revive his career. On his way to a 12-10 record in 1953, he pitched a no-hitter on July 4, beating the Sacramento Solons 1-0 in a seven-inning game. After posting 17 wins and a 2.32 ERA in 1954 for manager Bobby Bragan, Munger notched 11 wins for Almendares, also skippered by Bragan, in the Cuban winter league and led the team to the league title. At the age of 36 he had an improbable year in 1955, leading the PCL in wins (23), ERA (1.85), and complete games (25). “Like a lot of experienced hurlers, I am no longer a thrower, but a real pitcher,” Munger said.30 The Yankees attempted to sign him, but wouldn’t pay the Stars’ $50,000 asking price. When Bragan was named the Pirates’ manager for 1956, the team signed Munger to a major-league contract. Instead of resting for his big-league comeback, Munger opted to pitch in the Cuban league for the fourth consecutive season (effectively pitching year-round for four years). Struggling with Almendares, he was waived, signed with Havana, and finished with a 2-7 record, which foreshadowed his return to the Pirates.

Making the Pirates as a long reliever, the veteran made a start on June 2 and beat the Milwaukee Braves 4-2, pitching six innings and surrendering two runs for his first major-league victory in almost five years. In 35 appearances (13 starts), he won three of seven decisions and posted a 4.04 ERA in 107 innings, but was released at the end of the season.

Not ready to retire, Munger pitched for Mazatlan in the Mexican Winter League in 1956-57 and set a league record by pitching 34 consecutive scoreless innings, including three shutouts.31 After an undistinguished, injury-plagued year with the Seattle Rainiers in 1957 (6-10, 3.65 ERA), Munger was released in midseason by the San Antonio Missions in 1958, though he remained with the team through the rest of the season as an unofficial pitching coach. A ten-year major-league veteran, Munger finished with a 77-56 record and 3.83 ERA; he won 152 games in 12 seasons in the minor leagues.

Munger returned home to his wife and children in Houston, where he lived the rest of his life. He scouted for the Houston Colt 45s in 1961, worked as a salesman for a local brewery, and was a longtime private investigator for the Pinkerton Agency. At the age of 77, Red Munger died from complications of diabetes on July 23, 1996. He was buried in Forest Park Lawn cemetery in Houston.

Sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

BaseballReference.com

New York Times

Retrosheet.com

The Sporting News

Notes

1The Sporting News, March 18, 1937, 8.

2Dayton Record Chronicle, March 31, 1938, 2.

3San Antonio Light, April 7, 1939, 13.

4Calgary Herald, September 22, 1942, 8.

5The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 1.

6The Sporting News, April 26, 1945, 11.

7The Sporting News, June 14, 1945, 11.

8The Sporting News, October 18, 1945, 14.

9Milwaukee Journal, June 6, 1945, 35.

10The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 1

11The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 1.

12 The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 1.

13The Sporting News, September 18, 1946, 6.

14The Sporting News, October 16, 1946, 8.

15The Sporting News, September 3, 1947, 13.

16The Sporting News, August 13, 1947, 10, and October 22, 1947, 22.

17The Sporting News, May 12, 1948, 9.

18The Sporting News, June 16, 1948, 8.

19The Sporting News, June 23, 1948, 11.

20The Sporting News, September 4, 1946, 1.

21The Sporting News, August 10, 1949, 3.

22The Sporting News, August 10, 1949, 10.

23The Sporting News, September 7, 1949, 5.

24The Sporting News, December 19, 1951, 3.

25The Sporting News, February, 7, 1951, 13.

26The Sporting News, January 3, 1951, 16.

27The Sporting News, August 22, 1951, 22.

28The Sporting News, January 9, 1952, 18.

29The Sporting News, February 13, 1952, 9.

30The Sporting News, July 27, 1955, 27.

31The Sporting News, January 23, 1957, 26.

Full Name

George David Munger

Born

October 4, 1918 at Houston, TX (USA)

Died

July 23, 1996 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.