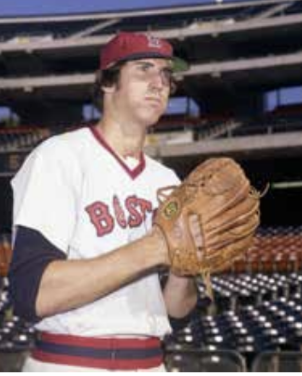

Rick Jones

When the Boston Red Sox broke camp in 1976 after winning the American League pennant the previous year, a young and relatively unknown left-hander claimed a spot on a roster that included future Hall of Famers Carlton Fisk, Fergie Jenkins, Jim Rice, and Carl Yastrzemski. The expectations weren’t high at such a young age, but Rick Jones, a lanky 6-foot-5, 190-pound pitcher from Jacksonville, Florida, who was the Red Sox fifth pick in the June 1973 draft found himself on a major-league roster before he had celebrated his 21st birthday.

When the Boston Red Sox broke camp in 1976 after winning the American League pennant the previous year, a young and relatively unknown left-hander claimed a spot on a roster that included future Hall of Famers Carlton Fisk, Fergie Jenkins, Jim Rice, and Carl Yastrzemski. The expectations weren’t high at such a young age, but Rick Jones, a lanky 6-foot-5, 190-pound pitcher from Jacksonville, Florida, who was the Red Sox fifth pick in the June 1973 draft found himself on a major-league roster before he had celebrated his 21st birthday.

As a prep, Jones held promise, having been named to the Florida All-State Baseball third team by the Florida Sports Writers Association,1 and earning a selection to play for the North squad of the state high school all-star baseball game at Lakeland’s Marchant Stadium.2

“I didn’t play in the game,” Jones said. “I was at practice with my Legion baseball team when I found out I had been drafted by the Red Sox. Two days later, I was on a plane.”3

Jones’s first stop was Elmira of the New York-Pennsylvania League. A short-season Class-A team, Elmira was 32-37 in 1973, with future major-league pitchers Luis Aponte and Allen Ripley joining Jones on the staff. At 18 years old, Jones appeared in 17 games, with 13 starts, and registered a 5-3 record with a 2.39 earned-run average and seven strikeouts per game. He pitched 98 innings, second most on the team.

In 1974, his first full season in professional baseball, Jones was assigned to Winter Haven of the Class-A Florida State League. Jones was 6-12 in 24 games (23 starts) for his 59-71 team, with a 3.65 ERA.

Jones began the 1975 season at Winston-Salem of the Class-A Carolina League, and it was the first step of a rapid ascent to the majors. Barely 20 years old when the season began, Jones posted a 13-3 record with 14 complete games and a 2.11 ERA. Considered the ace of the staff, he was promoted to Bristol of the Double-A Eastern League on July 2. He was named the Carolina League’s Topps Player of the Month award for June,4 and later was named the league’s Pitcher of the Year by league managers. For Bristol (81-57), Jones threw nine complete games in 12 starts and posted a 7-4 record.

Meanwhile the Red Sox won the American League pennant before losing the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds in seven games.

“In 1975, I had a good year,” Jones said. “After the season, I went to instructional league in Sarasota. Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson had a winter home in Sarasota, so he would come around occasionally and knew who we all were.”5

Spawned in part by judicial rulings regarding the reserve clause and the expiration of the collective-bargaining agreement, the owners announced on February 23, 1976, that spring-training camps would not open until a new agreement was finalized. With no place to report, Jones continued to work out with the Jacksonville State and University of North Florida college baseball teams, as he had most of that winter.

“The lockout delayed spring training,” Jones said. “I had been working out with the local college teams, so the delay didn’t hurt me at all. When spring training finally started, I was ready to go.”6

Jones pitched in three exhibition games that spring, tossing 4⅔ innings, allowing two hits, two walks, and no runs.7

“On the final day of spring training, it came down to me, Jim Burton, and Diego Segui,” said Jones. “We were told whoever pitched the best would get the last spot on the roster. Segui was average that day, Burton gave up back-to-back home runs against the White Sox, and I pitched well. When the game was over I was asked if my bags were packed. They weren’t — I figured I was just going to the minor-league camp, so when I found out I made the roster, I had an hour to get my stuff and get on the plane to travel north since I had made the team.”8

The first stop for the Red Sox was Baltimore, but Jones didn’t see any action in that series or the following two-game set with Cleveland. He finally saw mop-up action against the Chicago White Sox on April 18, 1976, two days after his 21st birthday, entering the game with the Red Sox trailing 8-2. He gave up four hits and two earned runs in two innings pitched.

His next outing didn’t occur for another 11 games, again wrapping up a lopsided loss, to the Texas Rangers after Luis Tiant surrendered nine unearned runs in the second inning. Jones faced 19 batters in four innings, again allowing two earned runs. His next six appearances followed a similar script: He pitched no more than two innings at a time without registering a win or save.

On June 13 Jones got his first major-league start, and he responded with a complete-game performance against the Twins at Metropolitan Stadium in Minneapolis. The Red Sox staked him to an early lead with a seven-run third, and although Jones surrendered two runs in a three-hit fourth inning, and by his own admission sported just a “mediocre fastball,”9 the Red Sox won, 10-2.

“I can’t think of any other pitcher like him,” said catcher Carlton Fisk about Jones’s performance that day. “Changeups starting hitters off, breaking balls, then he pops the fastball in pretty well.”10

With this performance, Jones became a regular starter in the Boston rotation. After 10 additional starts, he was 4-1 with a 2.34 earned-run average.

In an August 5 start at Detroit, Jones lasted just 2⅓ innings in a 5-4 Boston victory. Despite the win, the defending American League champions were a distant fourth place in the AL East with a 50-55 record, 14 games behind the division-leading Yankees.

Boston’s longtime owner Tom Yawkey had died on July 9, and just 10 days later, Johnson was fired as manager and replaced by Don Zimmer. The move was unpopular with a faction of the players, including Bill “Spaceman” Lee, who was the de-facto leader of the Buffalo Heads, an anti-Zimmer clique of players that included Fergie Jenkins, Lee, Rick Wise, Jim Willoughby, and Bernie Carbo.11

Jones’s association with this group of players wasn’t popular with Zimmer. When he missed a flight to California on August 9, he was demoted to the Triple-A Rhode Island Red Sox, in Pawtucket. With his steady performance up to this point, the move came as a surprise.

Peter Gammons, who often traveled with the Red Sox, accounted for the surprise demotion in his book Beyond the Sixth Game:

“When he missed a curfew or two, management blamed older players, particularly [Jim] Willoughby and Bill Lee, citing their wilder influences on this hayseed. But no one had to lead Tall Boy — so named by Willoughby after the Schlitz 16-ounce Tall Boy can and the fact that Jones was 6-foot-5 — astray. His high school buddies were three members of the rock band Lynard Skynard sic]; the band was named after principal Leonard Skinner, their high school athletic director and football coach, who had suspended the band members and Jones from the athletic program. Tall Boy unfortunately was ahead of his time as far as getting himself into trouble, and while he would return in September [1976] for a brief stay before going to Seattle in the expansion draft, he threw away what appeared to be a promising career.”12

Jones’s account differs slightly. “I had car problems driving to the ballpark to catch the bus that took us to the airport to fly to California. Right fielder Dewey Evans also missed his flight. I flew out later that day to California, and when I got to the hotel I called Zimmer’s room, no answer, and left a message. Also left a message in his box with the front office hotel clerk. I didn’t hear back from him until the next morning, when he told me I was being taken out of starting rotation and sent to bullpen.

“When I found out Dewey Evans was still going to start that night I was ticked and told Zimmer I didn’t know if I would be going to the game. I showed up late, and after the game was demoted to Pawtucket, they already had an airline ticket for me to fly that e night, and I arrived in Pawtucket the following morning. I pitched that night (Jones was the pitcher of record in a 7-4 loss to Rochester). Not going to game in California was the biggest mistake of my life. I found out later Zimmer was at a horse track when I first tried to contact him in California. Also found out later I probably got blackballed after that and probably cost me my big-league career, but it was my mistake.”

“I don’t know where that Lynyrd Skynyrd story came from, some band members did go to my high school, but they were older than me. I was in junior high when they were in high school.”13

While with the Rhode Island Red Sox, Jones was 0-3 with a 9.90 ERA. He was recalled in September, and his initial start was a Monday Night Baseball game in Yankee Stadium on September 6. Jones surrendered five hits and three earned runs in 2⅔ innings, with the Red Sox losing 6-5.

He subsequently didn’t get out of the first inning in a loss to Cleveland on September 11 but posted his fifth win of the season in a 12-6 victory over Detroit on September 20.

Jones’s final appearance for the Red Sox was a no-decision stint in relief of Tiant in a September 29 loss to the Yankees in Fenway Park. With the Red Sox, he won five games, lost three, and posted a 3.36 ERA.

Whether through rumored off-the-field troubles or simply a baseball decision, Jones was left unprotected by the Red Sox in the 1976 expansion draft. Seattle selected him as its 11th pick, reuniting him with Darrell Johnson, who was now managing the Mariners. He anticipated going to Seattle for Opening Day, but he didn’t initially make the roster out of spring training, instead being optioned to the Wichita Aeros of the Triple-A American Association.

As a first-year expansion team, the Mariners didn’t have a Triple-A franchise in 1977. (The Aeros were a Chicago Cubs farm team.) Jones was 0-2 in five appearances (one start) at Wichita before being recalled by the Mariners in early May.14 Although Jones was back in the majors, he wasn’t enamored with his surroundings.

“I had shipped my car from Phoenix to Seattle, and catcher Larry Cox drove it until I got called back from Wichita,” Jones said. “I loved Boston,” he continued. “To this day, I’m still a big fan of the Patriots and Celtics. Going to Seattle was tough — the fans were great, but the Kingdome was dark, and it just wasn’t the e.”15

Jones’s first start with the Mariners was a 4-2 loss at Baltimore, in which he allowed six hits and two earned runs in 4⅓ innings. In the next seven outings, he failed to register a win, although he didn’t allow an earned run in 5⅔ innings, during stints against Detroit (June 9) and Oakland (June 14). Both were wins for Seattle, but Jones didn’t figure in either decision.

On June 18 Jones had his longest outing with the Mariners, tossing 9⅓ innings and earning his only major-league victory with the expansion club, a 6-1 win at Texas. Jones faced 42 batters, giving way to Enrique Romo who faced one batter, inducing a double-play grounder from Ken Henderson. Jones walked 11 batters in the win, a Mariners record for most walks in a victory that still existed in 2018.16

Five days later, Jones surrendered three earned runs in three innings at Kansas City, but injured himself warming up for the fourth and couldn’t continue.

“I threw a curveball that went about 10 feet,” Jones said. “My arm felt like I was shot with a .22. At the time, everything had to go through the team doctor, and they decided to operate on my ulnar nerve. Today, I believe that’s considered Tommy John surgery.

“I was told I would be okay in about 30 days (he was placed on the 21-day disabled list), but two months later I still couldn’t brush my teeth. To this day, my left arm has a 30-degree bend in it.”17

Done for the season, Jones rehabbed and returned to Triple A in 1978, this time with the San Jose Missions, a Mariners affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. He started 20 games, posting a record of 7-8 and an ERA of 3.87.

A late season call-up to Seattle resulted in one relief appearance and two starts, both losses.

“After the injury, my control was okay, but I never got my speed back,” Jones said. “I never could get my fastball back.”18

After two seasons and minimal impact, Jones was traded to Pittsburgh on December 5, 1978, along with Enrique Romo and Tom McMillian, in exchange for Odell Jones, Rafael Vasquez, and Mario Mendoza. He left Seattle having won only one game in two seasons, the record-breaker in which he walked 11. He was now a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates, the soon-to-be 1979 World Series winner.

“In spring training with the Pirates in 1979, Harvey Haddix, my pitching coach, told me I had a good chance to make the team,” Jones said. “About two days before we broke camp, the Pirates signed Andy Hassler, and I was sent to the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League.”19

“I actually loved the Pacific Coast League,” Jones said. “We flew everywhere except Tacoma — it wasn’t like the other minor leagues.”20

Jones had solid seasons in Portland in 1979 (12-8, 3.59 ERA) and 1980 (10-11, 4.67 ERA) but he never made another appearance in the majors.

In 1981, his final year in Organized Baseball, Jones led the Mexico City Tigres to first place in the Southwest Division of the Mexican League. The Tigres lost to the Campeche Piratas in the playoffs, four games to one.

“I was invited to spring training with St. Louis as a nonroster player in 1982, but by then, I had kids and decided to hang it up,” Jones said. “The final player I faced in Mexico was Bill Buckner’s brother (Jim). I always thought that was interesting since I started with Boston and considering Buckner’s history with the franchise.”21

Thomas Frederick Jones was born on April 16, 1955, in Jacksonville, Florida, the youngest of five children of Marion F. “Dixie” Jones and Betty Bennett Jones. Known as Rick or Ricky, he attended Nathan Bedford Forrest High School in Jacksonville, a school that was renamed Westside High School in 2014 by the Duval County School Board in response to public outcry over the namesake, a Confederate general and first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.22

Jones’s father was a Navy veteran who served in the Pacific during World War II, had a short stint in professional baseball, and later became a longtime teacher at Forrest High School. He died in 2007.

His mother, who died in 2005, was a kindergarten teacher. She was married to Marion for 62 years before her death.

Kenneth Jones, Rick’s older brother, was drafted by the Washington Senators in 1965, but chose to attend Stetson University rather than sign with the Senators. He graduated from Stetson with honors in 1969 with a major in economics. He received a law degree from the University of Florida Law School in 1972.

Three sisters (Bette, Susan, and Rebecca) were born between Kenneth and Ricky.

When his baseball career ended, Jones returned to Florida. “I did different things, spent some time in sales, and worked for one company for over 20 years before they went out of business,” he said.23

“I coached my boys in Little League and Senior League. I never had a job I liked as much as playing baseball.”24

Jones said he continued to watch baseball on a regular basis, cheering for the Atlanta Braves. “Growing up in northern Florida, I’ve been a fan of the Braves my entire life,” he said.25

As of 2018, Jones was retired and lived in his native Jacksonville.

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Retrosheet, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 “All-State Baseball: Four Central Floridians Named to High School Team,” Orlando Sentinel, July 1, 1973: 65.

2 “MI’s Williams on ‘Star Team,” Florida Today (Cocoa, Florida), May 22, 1973: 2C.

3 Rick Jones, telephone interview with author, May 6, 2018 (May 6 interview).

4 “Jones Is Named CL Player of Year,” Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Telegram, August 21, 1975:15.

5 May 6 interview.

6 Ibid.

7 United Press International, “Red Sox Drop Segui, Reach 25-Man Roster,” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), April 7, 1976: 32.

8 May 6 interview.

9 UPI, “Rookie Jones Says He Had No Fast Ball in First Major-League Win Yesterday,” Berkshire Eagle, June 14, 1976: 26.

10 Ibid.

11 David Laurila, “Bill Lee Interview,” Baseball Almanac, baseball-almanac.com/players/bill_lee_interview.shtml.

12 Peter Gammons, Beyond the Sixth Game (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1985), 78.

13 Rick Jones, email exchange with author, May 7, 2018.

14 “Seattle Mariners Recall Rick Jones,” Miami (Oklahoma) News Record, May 16, 1977: 4.

15 May 6 interview.

16 Steve Rudman, “Pitching Improbables from Mariners History, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 11, 2006. seattlepi.com/sports/baseball/article/Pitching-improbables-from-Mariners-history-1203352.php.

17 May 6 interview.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Denise Smith Amos, “Duval School Board Backs Westside High School as New Name for Forrest High,” Florida Times-Union, January 7, 2014. https://jacksonville.com/news/2014-01-07/story/duval-school-board-backs-westside-new-name-forrest-high-school.

23 Rick Jones, telephone interview with author, May 18, 2018.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid

Full Name

Thomas Frederick Jones

Born

April 16, 1955 at Jacksonville, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.