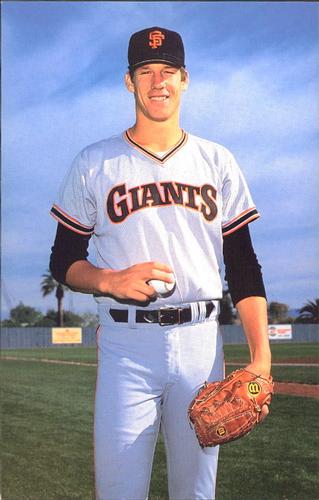

Roger Mason

Roger Mason had no idea that his first appearance as a Detroit Tigers pitcher would be a record-setting performance.

Roger Mason had no idea that his first appearance as a Detroit Tigers pitcher would be a record-setting performance.

Mason, in fact, had no reason to believe that he would even pitch in the major leagues, let alone in 1984 for the eventual World Series champions, or that he would go on to pitch in parts of nine seasons for seven major-league teams.

After all, it had been only four years earlier, in late August 1980, that Mason, then a 22-year-old pitcher from Bellaire, a town of 800 residents in northern Michigan, went to nearby Traverse City for what he determined would be his final tryout camp.

“I had been to several tryout camps before and I told myself that if I didn’t attract any interest this time, I would move on with my life,” he said. “But a month after I got home from the tryout, I got a call from a Tigers scout.”

Four years later — on September 4, 1984 — he found himself on the mound after suiting up as a Tiger for the first time that day. He was a late-season call-up from the Tigers’ Triple-A affiliate in Evansville, Indiana, where he had compiled a 9-7 record with a 3.80 earned-run average as a starting pitcher for the Triplets.

It was just the latest in a series of big steps that the right-hander made in crossing over from the west side of Michigan to the east side – with a goodly number of crisscrossing hops in between and afterward.

Roger Leroy Mason was born on September 18, 1957 — not 1958 as some sources report — at the Meadowbrook Care Facility in Bellaire, Michigan. He was the second of seven children born to Dorr and Betty Mason. Dorr was a mechanic and Betty was a stay-at-home mother. In high school, Roger was an all-state player not only in baseball but in basketball and football as well, playing wide receiver on the gridiron, forward in hoops, and, of course, pitching on Bellaire High School’s baseball team. By the time he graduated, he had grown to his pro height of 6-feet-6.

Mason carried on the three-sport excellence in college, becoming the first three-sport letterman in the history of Saginaw Valley State College. He lettered all four years in basketball and two years in football, but just one year in baseball. How could this be? Saginaw Valley didn’t offer baseball as a varsity sport when he enrolled. Baseball was just a club sport then. But college officials made it a varsity sport before he graduated; Mason was a pitcher on that first varsity team.

Mason hardly expected to toe the slab the evening of his big-league debut. Dave Rozema got the start that night for the Tigers. Three of the first four batters reached base against him. Manager Sparky Anderson, as usual, had little patience that evening, pulling Rozema after Cal Ripken’s sacrifice fly and Eddie Murray’s RBI single left the Tigers down 2-0. Lefty Bill Scherrer got out of the inning by retiring the next two batters, but then walked leadoff batter Wayne Gross in the top of the second inning.

“They told me to start warming up in the first inning, but I thought they were pulling a rookie joke,” Mason said. “Earlier, before the game started, Sparky had called down to the bullpen and kidded with Marty Castillo about his favorite college football team. So I didn’t know if it was a joke or not.”

It wasn’t. After Scherrer’s walk to open the second inning, the Tigers manager strode quickly to the mound, took the ball from the lanky lefty and motioned to the bullpen for Mason.

“I wanted to see what (Mason) could do,” Anderson said after the game. “I figured since he had been a starter in Evansville, this was a good spot for him.”

Mason, for his part, wasn’t quite sure how to act when he was signaled into the game.

“It started when I walked onto the field before the game,” he said. “Some writers were asking me if I was nervous, since I grew up in a small northern Michigan town rooting for the Tigers, then here I was in the middle of a pennant-winning season. I told them I wasn’t nervous, but I was hoping they wouldn’t see my legs shaking.”

He was still nervous when Anderson patted his right arm to bring him into the game.

“Seriously, I didn’t know whether to walk or jog or what the protocol was because I had been a starter my entire minor-league career,” he said with a laugh. “I decided I better not hold the game up. I ended up jogging to the mound.”

He remembered only two things about the game after that. The first thing was his first pitch in the majors. Baltimore’s Rich Dauer grounded into a double play. The second was a two-run home run by Rick Dempsey in the top of the fifth inning.

He said he didn’t remember striking out Ripken, the reigning American League Most Valuable Player, twice.

In all, Mason pitched eight innings in relief, giving up two runs in a 4-1 Tigers loss. His eight-inning relief performance set a Tigers record for a nine-inning game, a mark that, as of 2010, still stood.

Mason went on to win a game – almost the clinching game – and record a save for the Tigers as they marched toward postseason glory.

The game he won, against Milwaukee two weeks later, on September 17, would have been the clincher had Boston held on to beat Toronto later that night. But the Blue Jays rallied, and Mason’s win was good enough to clinch a tie for the AL East flag. The celebration was postponed for just one night; Randy O’Neal, another September call-up, got the victory. The pennant and the partying that followed, though, served as a mighty nice early 27th birthday present for Mason.

He earned his save in Yankee Stadium during the final series of the regular season. “I remember standing on the mound that night in Yankee Stadium” – actually, it was a day game — “rubbing up the baseball and thinking how far I had come from Bellaire to Yankee Stadium,” he said. “I thought about my dad and how we used to listen to Ernie Harwell and George Kell call the games on radio and TV. I guess outside of making the Tigers that year, my next biggest thrill was being interviewed by Ernie.”

Mason recalled great memories and only one regret about being part of the 1984 team.

“The excitement in Detroit was everywhere that year,” he said. “I loved coming to the ballpark. One of the things I remember most is how well [equipment manager] Jim Schmakel treated everyone, even us rookies. The whole experience of being a Tiger, even for a month, was unforgettable.”

Mason said he wished he had a World Series ring to make it even more memorable.

“The players vote on postseason shares [money] and they gave it to the six of us who were called up in September,” he said. “Management decided who got World Series rings and the six of us didn’t get one. That’s the one thing I wished I had gotten out of that experience; it would have been a nice memento.” The unlucky six were Mason, Scott Earl, Mike Laga, Randy O’Neal, Nelson Simmons, and Dwight Lowry, who had gotten a call-up earlier that season.

But Mason wasn’t complaining. He realized how far he had come to be part of the 1984 Detroit Tigers.

He recalled the circumstances of living with a wife and child while pitching in the Double-A Southern League for Detroit’s affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama. “It was a struggle getting by. I made $422 a month and that went for rent and our car,” Mason said. “My wife, Terry, and I had a young son [Jeff] and we made it because Terry waited tables at a Cracker Barrel and her sister came down to live with us. When one of them was working, the other was watching Jeff.” There weren’t any performance bonuses in the bushes, or else Mason might have had a thicker wallet for leading the league in ERA at the all-star break.

Mason got his payday down the road, signing for $500,000 in 1994 for the Philadelphia Phillies. But the strike cut into that number, and he didn’t even spend most of the shortened season with the Phillies, who sold him that April 29 to the New York Mets.

Between 1984 and 1994, Mason bounced around. He was traded by the Tigers to the San Francisco Giants for outfielder Alejandro Sanchez before the start of the 1985 season. He won five games in three years for the Giants from 1985 to 1987, spending much of that time in the minors.

Mason was granted free agency by the Giants after the 1988 season, during which he made no appearances with the parent club, and signed with Houston on February 16, 1989, appearing in only two games with the Astros that year, and going through the entire 1990 season with no major-league action. He didn’t hit his major-league stride until he got to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1991. He was a key part of the Pirates’ bullpen for two years.

That’s where he got to know Barry Bonds. Sort of. Mason had surrendered Bonds’ eighth career home run on July 25, 1986, at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh. Five years later, they were battling together to help Jim Leyland’s team win a National League East Division title.

“I was Barry’s teammate for two years with Pittsburgh,” Mason said with a smile. “But I don’t think he knew who I was.”

Mason pitched in five National League Championship Series games for the Pirates in 1991 and 1992, allowing no runs in 7⅔ innings of relief. He earned a save in Game Five of the 1991 NLCS. He relieved starter Zane Smith with two outs in the eighth inning and Atlanta’s Terry Pendleton on third base, with Pittsburgh leading the Braves 1-0. Mason got Ron Gant to pop up, and then went on to retire the Braves in the ninth, despite giving up two singles, and preserving the 1-0 victory.

After being released by Pittsburgh following the 1992 season, Mason was signed by the Mets on December 2, 1992. Fifteen days later, on December 17, he was traded to San Diego with minor leaguer Mike Freitas for pitcher Mike Maddux. After going 0-7 with a 3.24 ERA for the Padres, he was traded again, on July 3, 1993, this time to Philadelphia for pitcher Tim Mauser. He went 5-5 for the Phillies and was a standout in the postseason that year.

Mason made two appearances in the NLCS, pitching three scoreless innings. In the 1993 World Series, he pitched in four games, limiting the Toronto Blue Jays to one earned run in 7⅔ innings. He was in line to be the winning pitcher in two of those World Series games before the Phillies’ bullpen fell apart, climaxed by Joe Carter’s Series-clinching home run off Mitch Williams.

“Pitching in the 1993 World Series was a great experience,” Mason said. “I felt a calmness out there on the mound. I think that was reflected in my numbers.”

He started the 1994 season with the Phillies and was 1-1 with a 5.19 earned run average before being sold to the Mets. That’s where he finished his career, going 2-4 with a 3.51 ERA.

That came 10 years after his debut with the World Series champion Tigers.

“I look back at how far I came from my final tryout camp to what I accomplished and I have to say I feel very fortunate,” Mason said.

“I think back to that very first spring I spent in Tigertown with all the other minor-league players. We were assigned to dorm rooms and every floor on the dorm had bulletin boards. That’s where they posted which players had made it and which had been released or reassigned. I kept checking to see if I was let go, but luckily my name never made that list. I survived.”

Mason’s final major-league totals are those of a survivor. He played for seven teams in nine big-league seasons over 11 years, posting a 22-35 record and a 4.02 ERA, pitching 416⅓ innings in 232 games and earning 13 saves along the way.

Mason was a teammate of Hall of Famers Tony Gwynn and Steve Carlton. He pitched for a World Series winner. He was a standout in the 1993 World Series, though for the losing team. He also experienced the humbling side of the game.

He gave up three home runs to start a game, a major-league record, surrendering four-baggers to San Diego’s Marvell Wynne, Tony Gwynn, and John Kruk in the bottom of the first inning of an April 13, 1987, contest while pitching for the Giants. On a windy day in Wrigley Field two weeks later, on April 29, he lined what would have a sharp single to right field – had he not been thrown out at first base.

“Stick around long enough and the game will humble you,” Mason said. “You just have to keep believing in yourself.”

The tiny town of Bellaire still does. The Masons retired to Roger’s home town. He established the Northern Michigan Hour of Prayer Bible study group with Terry, a nurse, in 2005. Their two children, Jeff and Amy, are grown.

“As it turns out, Detroit was only my first stop in the big leagues,” Mason said. “I would have been satisfied if 1984 had been my only year. I consider myself lucky to play for my home team in my home state in one of the best years in Tigers history. It doesn’t get any better than that.”

Last revised: July 1, 2012

This biography is included in “Detroit Tigers 1984: What A Start! What A Finish!” (SABR, 2012), edited by Mark Pattison and David Raglin.

Full Name

Roger Leroy Mason

Born

September 18, 1957 at Bellaire, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.