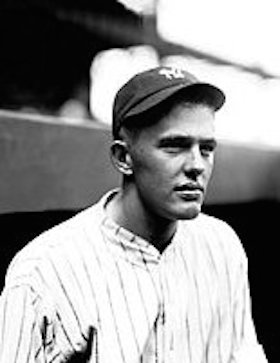

Roy Luebbe

Roy Luebbe has the distinction of being the only Butler County, Iowa, native to play major-league baseball. Roy John Luebbe (pronounced Loo-bee) was born on September 17, 1900, in Parkersburg population 1,164, an agricultural community in Butler County in the north central part of the state. He and twin brother Ray were the fourth and fifth of seven children born to Heinrich (H.M.) and Annie Luebbe. The couple immigrated from the Schleswig-Holstein region of Germany in 1893 and H.M. worked as a butcher. The family moved to Omaha sometime between 1903 and 1910 and H.M. worked at a butcher shop for a few years before purchasing his own butcher shop and later a grocery and meat market.

Roy Luebbe has the distinction of being the only Butler County, Iowa, native to play major-league baseball. Roy John Luebbe (pronounced Loo-bee) was born on September 17, 1900, in Parkersburg population 1,164, an agricultural community in Butler County in the north central part of the state. He and twin brother Ray were the fourth and fifth of seven children born to Heinrich (H.M.) and Annie Luebbe. The couple immigrated from the Schleswig-Holstein region of Germany in 1893 and H.M. worked as a butcher. The family moved to Omaha sometime between 1903 and 1910 and H.M. worked at a butcher shop for a few years before purchasing his own butcher shop and later a grocery and meat market.

The 1920 census lists 19-year-olds Roy and Ray as living at home; Roy’s occupation is “laborer” for a wholesale furniture company and Ray is “in school.” The Luebbe boys played amateur baseball on the Omaha sandlots in 1919, 1920, and 1921 for such teams as the Riggs Opticals and the Bowen Furnitures. Ray played second base and Roy right field for the 1919 Paxton-Vierling Ironmen. Coaches moved Roy from outfielder to catcher after observing his strong right throwing arm. Roy was a switch-hitter, standing 6-feet and weighing 175 pounds at age 20. After the 1921 amateur season finished, Barney Burch, owner of the Omaha Buffaloes in the Class A Western League, selected Roy Luebbe as the most promising local player and signed him to a professional contract. Because the Buffaloes were fighting for a pennant, Roy served as bullpen catcher and never played in a game.

In the spring of 1922, Omaha native Pat Ragan recruited Roy and five other players from the Omaha area to play for the Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks team that he managed. The Hawks competed in the newly formed Class D Mississippi Valley League. Waterloo’s ballpark, located less than 25 miles from Parkersburg, was the first stop on Roy’s professional baseball journey. Meanwhile, Ray was released in June from his Omaha amateur team and continued his schooling. Manager Ragan assembled a pretty good Class D team; four players from the 18-player roster eventually played in the major leagues. The most successful was Freddy Leach, who hit .307 in 3,996 major-league plate appearances.

For the 1922 season, Roy hit .241 in 108 games and tied for the team lead in doubles with 17. Fielding statistics, sketchy as they are, credited him with 95 assists in 80 games as a catcher. Burch called Roy “a promising catcher” with “one of the best arms he has ever seen,”1 but not a strong hitter. The Rochester Tribe of the Double-A International League saw enough promise in Luebbe’s play to purchase his contract with the provision that he report at the end of the season. (AA, or Double-A, was the highest minor-league classification in 1922.)

The Philadelphia Phillies invited Luebbe to 1923 spring training and employed him exclusively as a bullpen catcher. When spring training ended, the Phillies sent him to the Scranton Miners in the Class B New York-Pennsylvania League. During his 10th game behind the plate, a foul tip broke his right thumb and the Phillies released him unconditionally. Luebbe returned home until the injury healed, then joined Grand Island (Nebraska) of the Class D Nebraska State League. Playing in only 63 games, Luebbe put up unusual numbers: a team-high 10 home runs in 195 official at-bats and a batting average of .200. Grand Island sold Luebbe back to the Phillies.

The Phillies again invited Luebbe to their 1924 spring training camp. Irish Carrig, a scout visiting the Phillies’ camp, wrote that “Luebbe looks mighty good. He certainly ought to make it this year.”2 A sore arm cut short his tryout and once again he returned to Omaha. After the arm recovered, Luebbe went back to the Grand Island club, now in the Tri-State League, but when the league disbanded on July 17 he signed with the Omaha Buffaloes and hit .300 in 36 games for the Western League champions. He signed a 1925 Buffaloes contract and got off to a fast start. The Associated Press in early July described Luebbe as “a great hitter,” adding, “He’s a turn batter and a stellar pinch clubber. In 40 games he hung up an average of .426. Big league scouts have their optics on him, according to reports.”3

Meanwhile, the New York Yankees were stumbling through May and June of 1925 without the hitting and fan appeal of George Herman “Babe” Ruth. This was the spring of Babe’s “Belly Ache Heard ’Round the World,” when he collapsed twice in railroad depots en route from Florida spring training to New York City before being hospitalized and undergoing surgery for an “intestinal abscess.” He didn’t play his first game until June 1. After 41 games, the Yankees languished in seventh place, 13½ games out of first place. Subpar performances from stalwart members of the 1923 World Series champions, especially middle infielders and catchers, and empty seats in two-year-old Yankee Stadium spurred the team’s owner, Colonel Jacob Ruppert, to cast about for new talent. Minor-league farm systems had not yet developed; common practice was for major-league teams to buy promising players from independent minor-league teams. Over the next six months, Ruppert acquired 24 new players at an estimated cost of $350,000.

So it was that on July 24 the Yankees purchased catcher Roy Luebbe from the Omaha Buffaloes (also called the Burch Rods after owner Barney Burch) for $12,500 cash and two players Omaha would select later. His annual salary was $2,100. Luebbe’s hitting had cooled off to a .370 batting average for 51 games, two points lower than the eventual league batting champion. Burch needed the money to cover losses at the gate as the 1925 Buffaloes had slipped into seventh place. His deal with Ruppert came months after the Associated Press mistakenly reported a spurious trade at the winter baseball meetings. Burch, the AP wrote, sent Luebbe and catcher P.J. Wilder to the league rival St. Joseph Saints in exchange for an airplane – certainly one of the most unusual trades in baseball history!4 Later Burch disclosed that the Saints owner was only joking and that a reporter took him seriously.

An Eastern newspaper described Luebbe as a “lanky youngster (who) has the looks of a first class backstop but there is little chance of his taking Benny Bengough’s job from him.”5 Omaha newspapers portrayed Roy as the classic case of hometown boy makes good. A wire-service story in August touted a “Yankees’ pony battery” featuring catcher Luebbe and pitcher Jim Marquis, both 24-year-old rookies.6 They were never to play in the same game. Marquis ended his two-game major-league career with a 9.82 ERA and had already pitched his last big-league game when the story was printed.

Yankees manager Miller Huggins, lauded by baseball historians for his ability to judge raw baseball talent, told reporters that Luebbe would be given the rest of the season to prove his worth. The original condition of the deal was that he would finish the 1925 season with Omaha, but apparently Huggins wanted to get an earlier look at Luebbe’s hot bat, so he optioned a locally popular catching prospect, Colgate graduate Honey Barnes, to Albany.

During the first few days of August, Luebbe acclimated to the grandeur of New York City, Yankee Stadium, and the expectations of manager Huggins. The Yankees carried three catchers, Luebbe, Bengough, and Wally Schang, a 13-year veteran who had played on three World Series winners, but his hitting had dropped off amid rumors that his eyesight was failing. Schang had a reputation as an energetic and likable teammate and mentor to many players. Thus he is the most likely player or coach to have worked with Roy.

Two players from the 1925 Yankees recalled the culture of that team. Pitcher Waite Hoyt said that the Yankee “philosophy and practice in its approach to the game” was superior to any other. “You sat on the bench and weren’t allowed to talk about anything but baseball and yell at the other club. … It was discipline at its highest.”7 Pitcher Sam Jones recalled, “The Yankees always did things in a big way. Why, when the season was over they’d even give each player three brand-new baseballs. Just give them to us. No other clubs did that.”8

Roy finally debuted behind the plate on August 22 in front of about 5,000 fans at Cleveland’s Dunn Field, batting seventh and going 0-for-2 with a walk in a 5-4 Yankee loss. He threw out one of two baserunners attempting to steal. The next day Luebbe was again in the Yankees’ starting lineup and came off the bench on August 24 and 27. He started four games in September, each game part of a doubleheader, the last on September 19.

Even though the Yankees were in seventh place, 29 games out of first place, on September 19, manager Huggins seems to have seen enough of Luebbe. Bengough caught most of the remaining games, including both ends of a September 28 doubleheader and all of a 10-0 loss on October 2. Furthermore, on August 30, Ruppert purchased veteran catcher Pat Collins from St. Paul for $25,000 and three players. Luebbe finished the season with no hits in 15 at-bats. He struck out six times and drove in three runs with a walk, a fielder’s choice, and a sacrifice fly. During the winter the Yankees optioned Luebbe to Class A Atlanta and he would never play in another major-league game.

Immediately after the season ended, Luebbe joined Babe Ruth’s exhibition team as a reserve catcher. After two games on Long Island, he left the team and boarded a train for Omaha. He arrived in time to suit up for an October 11 exhibition game at League Park. Luebbe was invited to be the catcher for the Dodgers’ Dazzy Vance, fresh from a 22-9 season including a no-hitter. They formed an all-Nebraska major-league battery in the first game of the Vance-Alexander exhibition tour. Vance and Cubs pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander grew up in Nebraska and are claimed as Hall of Fame members from that state. Iowa historians include Vance and Luebbe as native Iowans though both moved to Nebraska at an early age.

Luebbe’s sojourn through the minor leagues continued in 1926 when he hit .233 in 48 games with Atlanta, but more memorable was that 25-year-old Roy shared a room with a 20-year-old brash and talkative shortstop, Leo Durocher (who hit .238). From 1927 through 1930, Luebbe played in the Class B Sally League, first with the Asheville Tourists for two years and then for the Charlotte Hornets for two years. When he reported to Asheville’s 1928 spring-training camp five days early, manager Ray Kennedy asked if he expected to board at the club’s expense. Luebbe proposed that the club pay only if he hit .275 for the season. Kennedy took the bet; Luebbe hit .290. The following year, he made national news again, this time for being caught chopping down a tree growing outside the Charlotte ball park’s left-field fence. He said the leaves rustling in the wind distracted him when he was batting.

Luebbe’s performance in the Sally League drew considerable fan interest and may account for his returning year after year. A Charlotte sportswriter claimed the blond, boyish-looking athlete was a big drawing card with the ladies. The ladies must have been disappointed when Roy married Pearl Keefer, daughter of a Papillion, Nebraska, farmer, on February 15, 1930, and she accompanied him to Charlotte for the baseball season.

In 1928 Luebbe’s work behind the plate was compared favorably with that of the Macon Peaches’ 20-year-old catcher Al Lopez. Luebbe battled for the Sally League home-run leadership in 1930, but faded to finish fourth with 13. According to newspaper accounts, he challenged the Peaches’ 20-year-old Paul Richards for best defensive catcher in the league.

Luebbe’s reputation varied from “fan favorite” who would kid along with fans to the league’s “bad boy” whose fiery temperament got him tossed from many games. Pumping up enthusiasm for a late-season game in 1930, a Charlotte Observer reporter described Luebbe as “the terror of umpires, the most aggressive and truculent ballplayer in the league on the playing field but a most mild-mannered young man after the game.”9

After nine years of laboring in the minors, Luebbe was drafted by the Boston Braves in October 1930 for another opportunity to play in the big leagues. He finished the 1930 season with Class B Charlotte, hit .280, and, displaying his renowned arm, recorded an amazing 101 assists in 104 games. He earned a reputation as “a first-rate catcher and a top-notch judge of pitching talent.”10 The Omaha World-Herald summarized his chances: “He’s big” – Luebbe now weighed about 200 pounds – “he’s got the arm and the hustle and he is well-seasoned; and so Roy Luebbe may make the grade this year and become the second Omahan in the big leagues.”11 But bad luck struck again; during spring training an errant foul ball broke the middle finger of Luebbe’s throwing hand. Boston did not own any farm teams and was not willing to wait for the injury to heal, so Luebbe was left to find his own job. Later that season, he rejoined the Asheville Tourists, now in the Class C Piedmont League, for 78 games and finished the season with Class A Omaha.

Luebbe retired from professional baseball after the 1932 season and returned to Omaha to take a full-time warehouse job with General Electric Supply Company. He continued to work for GE in Omaha for over 30 years before retiring as warehouse superintendent. Twin brother Ray graduated from Creighton University Law School in 1925, was admitted to the Nebraska Bar, and rose to general counsel and vice president for the General Electric Corporation. His oldest brother, A.H., owned an electrical supply company in Omaha that was purchased by GE in 1927.

Roy Luebbe maintained his identity as a ballplayer by performing for Omaha semipro teams like the Robin Hoods and the Ford V-8s. In July 1935 the V-8 team won the Nebraska state semipro tournament and was invited to the first National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The V-8s assembled the 17 best semipro players from Omaha including 35-year-old Roy Luebbe, who played outfield and catcher. Omaha won its opening game, over the Wewoka Indians, winner of the All-Indian Tournament, lost its second game (in a double-elimination tournament) but rebounded to upset host Wichita and the Memphis Negro Red Sox. During the Memphis game Roy was batting when he and the Red Sox catcher “suddenly and without warning to fans started swinging at each other.”12 Players and fans swarmed the field but order was restored and Luebbe promptly lined a single.

The V-8s advanced to a semifinal game against the Bismarck (North Dakota) Churchills, whose roster included the greatest African-American pitchers of that time. Bismarck’s starting rotation for the tournament was Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith (both later elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame), Double Duty Radcliffe (so named because he was both a pitcher and a catcher), Barney Morris, and Chet Brewer, who among them combined for a 55-6 record for the Churchills that summer. Bismarck beat Omaha handily, 15-6, and swept the NBC tournament championship.

After his active playing days were over, Luebbe participated in old-timer’s games and was a special guest at several Class A Omaha games. As a member of the 1924 Buffaloes championship team, he was selected for first-pitch honors at the 1951 Opening Day ceremonies honoring Omaha’s 1950 Western League champions. On such occasions he was usually introduced as a former player with the New York Yankees. He had the honor of sharing a clubhouse with outstanding individual players; five teammates, Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earle Combs, Herb Pennock, and Waite Hoyt, and manager Miller Huggins were elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame. Occasionally Luebbe was recognized as one of “the greats who played some amateur ball in Omaha.”13

Roy and Pearl Luebbe raised two children, Richard and Beverly. Roy Luebbe died in Papillion on August 21, 1985, which, coincidentally was one day before the 60th anniversary of his Yankees debut. He is buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Omaha, the city he considered home.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball-Reference.com

GenealogyBank.com

Omaha Public Library

United States Census Bureau, 1910, 1920, and 1930 Censuses

Wikipedia

Notes

1 “From Sandlot to Rochester,” Omaha World-Herald, July 22, 1922.

2 “Former Omahan Looks Good With Phil,” Omaha World-Herald, March 20, 1924.

3 “Luebbe Hitting Well,” Iowa City Press-Citizen, July 14, 1925.

4 “Wilder and Roy Luebbe Swapped for an Airship for Owner Barney Burch,” Omaha World-Herald, December 3, 1924.

5 Bridgeport Telegram, October 7, 1925.

6 “Yankee’s Tot Battery,” Appleton Post-Crescent, August 19, 1925.

7 Eugene Murdock, Baseball Between the Wars: Memories of the Game by the Men Who Played It (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Publishing Company, 1992), 53.

8 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Macmillan and Company, 1966), 244-45.

9 Charlotte Observer, August 23, 1930

10 “Fanning and Panning,” Charlotte Observer, January 14, 1931.

11 “Roy Luebbe, Making Third Trip to Majors, Says He’ll Stick…,” Omaha World-Herald, October 12, 1930.

12 “Fords Defeat Red Sox, 6-5,” Omaha World-Herald, August 25, 1935.

13 “More Names From the Past,” Omaha World-Herald, October 5, 1979.

Full Name

Roy John Luebbe

Born

September 17, 1900 at Parkersburg, IA (USA)

Died

August 21, 1985 at Papillion, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.