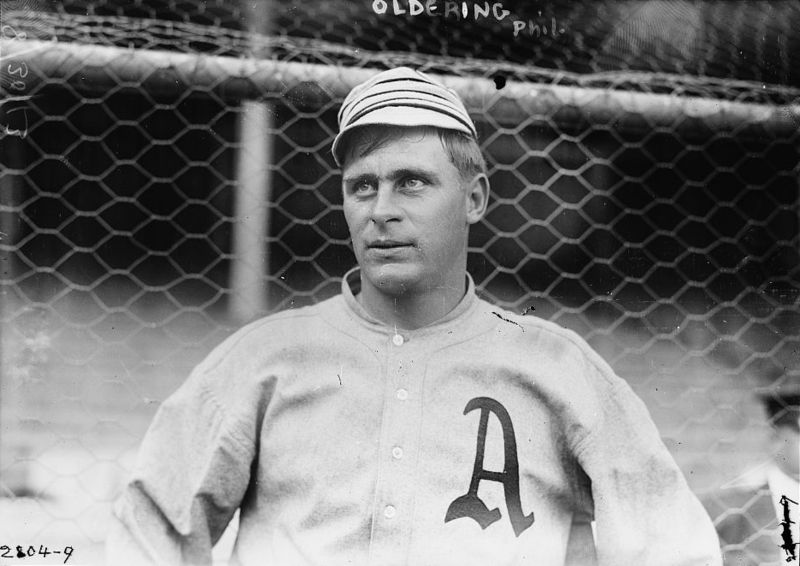

Rube Oldring

A prominent and popular member of the Philadelphia A’s dynasty of the Deadball Era, Rube Oldring patrolled the outfield grass of Columbia Field and Shibe Park for 12 seasons. He combined power, speed, and average for Connie Mack‘s championship teams of the 1910s, although frequent injuries limited his playing time. When healthy, Rube was described by Irwin Howe, the official statistician for the American League, as “a fast and reliable outfielder, good at laying down a bunt, and…a fast and intelligent baserunner.”

A prominent and popular member of the Philadelphia A’s dynasty of the Deadball Era, Rube Oldring patrolled the outfield grass of Columbia Field and Shibe Park for 12 seasons. He combined power, speed, and average for Connie Mack‘s championship teams of the 1910s, although frequent injuries limited his playing time. When healthy, Rube was described by Irwin Howe, the official statistician for the American League, as “a fast and reliable outfielder, good at laying down a bunt, and…a fast and intelligent baserunner.”

Reuben Noshier Oldring was born May 30, 1884 in New York City, one of eight children and the youngest of three sons of Thomas, an English immigrant, and Sarah Oldring. Reuben took to baseball early. By the age of fifteen he was traveling to New Jersey to play ball. He first played semipro ball for the Ontario team, which played at 147th Street and Lenox Avenue in New York. Rube hooked up with the Hoboken, New Jersey, club in 1905, when a scout for the Montgomery, Alabama, team of the Southern Association spotted the young right-hander and offered him a contract. Oldring played 67 games in the outfield and at shortstop, first base, and third base for Montgomery in 1905, batting .272 and stealing 23 bases. Connie Mack received a tip about Rube from Tom O’Brien, the Montgomery manager, and purchased Oldring’s contract near the end of the season.

Rube reported to Philadelphia on September 23, 1905 and was told by Mack that he was ineligible for the World Series and might as well go back home to New York and get into some semi-pro games before reporting to the A’s the following spring. Rube followed Mack’s advice, and played for a Manhattan semipro team in an exhibition game against the New York Highlanders. Oldring belted a three-run home run that enabled his club to top the major leaguers, 7-5. Clark Griffith, the New York manager, was shorthanded due to injuries. Impressed by Oldring’s play that day, he invited Rube to finish the season with the Highlanders. They settled on $200 for the week. Oldring played in eight games at shortstop, batting .300 with one home run. Griffith tried to draft Oldring, only to find that he was already the property of the Philadelphia A’s.

During spring training in 1906, Rube battled several players for a starting position and was told he had earned the starting third base job. The same day he received this welcome news, Oldring broke his right ankle sliding into third base and missed the start of the season. He returned to action in June, playing in 59 games, primarily at third. Rube had a powerful arm, and often overthrew first base, resulting in 16 errors in 49 games at the hot corner. When Oldring received his contract for 1907 there was a letter from Mack enclosed. “From this day on you will be my center fielder,” Mack wrote. “You will have all the room you want and will not have to throw the ball over anybody’s head.”

For the next ten years, Rube patrolled the outfield for the A’s. He played primarily in center field, moving to left field later in his career. The A’s were beginning to assemble their championship team and finished a close second to Detroit in 1907 and again in 1909. They finally emerged as champions in 1910, well ahead of second place New York. Rube had the best year of his career that summer, finishing in the top ten in the American League in batting average (.308), slugging percentage (.430), hits (168), total bases (235), doubles (27), triples (14), and home runs (4).

To prepare his underdog team for the World Series against the Chicago Cubs, Mack arranged a series of exhibition games against an American League all-star team. Unfortunately for Rube, he sprained his knee trying to dodge a fly ball he had lost in the sun; Oldring did not contribute to the A’s surprising five game upset of the Chicago Cubs.

The A’s won the American League championship again in 1911, and Oldring had another fine season, batting .297 with 84 runs scored, 21 stolen bases, and 26 sacrifices. This time the A’s faced the New York Giants in the World Series and Rube got his biggest thrill in baseball when he hit a three-run home run off Rube Marquard in Game Five. The A’s repeated as world champions, beating the Giants in six games.

Philadelphia’s string of championships stopped in 1912 as they slipped to third, fifteen games behind the Red Sox. Oldring batted .301 in 99 games, but ended up suspended by Connie Mack on September 6 for being out of condition. His roommate for 10 years, Chief Bender, was suspended at the same time. As Rube later told the story, the two of them drove to New York from Washington, rather than traveling with the team, and stopped to visit some friends along the way. The Chief dropped Rube at home in New York at 3 a.m. and proceeded to the team hotel. It was not the first such incident, and the next day, Mack called Oldring as he entered the clubhouse. “Rubie, you go in and take off that uniform. You’re going home. And you’re going to stay there. You’re not going west with us. Just try getting to bed before three o’clock if you wanna play baseball.”

In 1913 the A’s and Oldring returned to their championship form. The A’s finished first by 6½ games and Rube batted .283 with 101 runs scored and 40 stolen bases. Rube shifted to left field in 1913, and also filled in at shortstop for a week while Jack Barry was hurt. Rube himself missed several weeks with a broken nose suffered during an exhibition game to honor Harry Davis. The A’s took the World Series from the New York Giants, and Oldring contributed in Game Four with one of the finest catches of the Series. With runners on the corners and one out in the top of the fifth, Oldring snagged a sinking liner off the bat of pinch-hitter Moose McCormick, and then prevented the runner on third from tagging up on the play. The Athletics went on to win the game, 6-5, and the Series in five games. That year the Philadelphia fans honored Rube as the most popular baseball player in the city, and awarded him a new Cadillac.

The Philadelphia team won its fourth pennant in five years in 1914. Rube’s statistics slipped somewhat that year as he suffered several nagging injuries that cut his playing time to 119 games. In that year’s World Series against the Braves, Rube, like most of his teammates, had a horrendous series, collecting only one hit in 15 at-bats. Unlike his fellow Athletics, however, Rube had a unique excuse for his woes at the plate. Right before the World Series began, Rube announced that he was getting married. A woman who saw the news in the paper filed charges of non-support and desertion, claiming she was his common-law wife, Helen I. Oldring. The Boston Braves fans picked up on the story and razzed Rube continuously throughout the Series. Rube said, “I know I didn’t play as I should, and I attribute it to this trouble.” Apparently Rube did live with this other woman at one time, as the 1910 census lists her as his wife of two years. (Bizarrely, Oldring has two separate entries in the 1910 census. One entry, recorded in Manhattan on April 15, 1910, lists him as single, while the second entry three days later in Philadelphia lists him as married.) However, Rube told reporters that she was after his World Series money and that he had not seen her for more than two years. The matter was settled quietly, and Rube married Hannah Thomas on October 16, a marriage that lasted almost 47 years. He also announced the first of at least five retirements from baseball, though it was soon rescinded.

After the A’s stunning loss in the 1914 World Series, Connie Mack began dismantling his championship team. Rumors had Oldring ticketed for New York, but 1915 found Rube still with Philadelphia. The team went from first to last, winning only 43 games. Rube hit a career high six home runs–three times more than anyone else on the team–but his batting average slipped to .248 and he played in only 107 games. Rube and his wife had settled on a farm in New Jersey and he announced his retirement from baseball. However, Mack persuaded him to return to the A’s again for the 1916 season. Rube played in 40 games before being given his unconditional release on July 1. He returned to his farm, but was enticed to play for his hometown New York Yankees, due to injuries to their outfielders. Rube played in 43 games for New York, before the Yankees released him on September 9. Rube sat out the 1917 season to tend to his farm, but Connie Mack prevailed on him to return to the A’s one more time in 1918. Rube played in 34 games before hanging up his spikes for the final time in the major leagues. His batting average was a career worst .233. Due to his age, Rube was exempt from the War Department’s work-or-fight order, but he took a job playing baseball in the shipyards anyway.

Following the end of the war, Rube embarked on a peripatetic journey through the minor leagues. In 1919, Rube took a player/manager position with the Richmond Colts in the Virginia League, leading them to the pennant. Over the next six years, Oldring spent time playing and managing in Suffolk, Seattle, New Haven, Richmond again, and Wilson (NC), before finally rounding out his baseball career with a third stint in Richmond in 1926. After guiding that club to another pennant, Oldring finally retired from baseball for good and settled into farming until he sold his farm in 1939. He then took a job with a canned vegetable manufacturer, the Phillip J. Ritter Company, evaluating crops in the New Jersey area.

Rube suffered a heart attack in 1960, and died at age 77 on September 9, 1961, at his home in Bridgeton, New Jersey, from acute blockage of the arteries. He was survived by his wife Hannah, son Reuben Jr, and stepson Clarence Gordon, and is buried at Cohansey Baptist Church of Roadstown, located in Bridgeton.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

U.S. Census, 1910, 1920, 1930

Newark Sunday News, 8/19/1951

New York Times, 7/11/1916, pg 10

New York Times, 5/28/1954, pg. 23

New York Times, 5/30/1922, pg. 18

New York Times, 7/28/1916, pg. 8

New York Times, 11/27/1914, pg. 9

New York Times, 9/25/1913, pg. 11

New York Times, 10/17/1914, pg. 12

New York Times, 11/15, 1911, pg. 12

New York Times, 10/02/1905, pg. 7

New York Times, 9/5/1952, pg. 20

New York Times, 10/14/1910, pg. 12

New York Times, 12/4/1910, pg. C6

Trenton Evening Times, 5/20/1916

Trenton Evening Times, 5/30/1916

Los Angeles Times, 7/23/1949, pg. B2

Washington Post, 1/16/1923, pg. 18

Washington Post, 9/10/1922, pg. 52

Washington Post, 7/16/1921, pg. 8

Washington Post, 9/10/1916, pg. 53

Washington Post 9/7/1912, pg. 9

Washington Post, 8/25/1913, pg. 6

Washington Post, 1/16/1923, pg. 18

Atlanta Constitution, 8/4/1922, pg. 12

Baseball Digest, Jan. 1951, pgs. 61-62

Spalding Official Baseball Guide, 1906, pgs. 197-203

Baseball Magazine, Sept. 1911,No. 5, pg. 34

Baseball Magazine, Nov. 1914, No. 4, pg. 108

Chicago Daily News, 7/20/1918, pg. 9

Chicago Daily News, 10/9/1912, pg. 23

Sporting News, 10/29/1936, pg. 5

Sporting News, 9/20/1961, pg. 26

David Jordan. The Athletics of Philadelphia. McFarland, 1999.

Joe DeLuca. Diamond Heroes of South Jersey. Bridgeton Antiquarian League, 2000.

Full Name

Reuben Henry Oldring

Born

May 30, 1884 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

September 9, 1961 at Bridgeton, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.