Russ Gibson

For baseball fans in New England, the 1967 season is known as the “Impossible Dream,” and for Russ Gibson it was doubly a dream fulfilled.. After toiling in the minors for ten years, 1967 was the year he achieved his dream of playing for the Boston Red Sox, his hometown team. Baseball writers of the time would so often refer to Gibson’s long minor league career that one would think “10-year Minor Leaguer” or “28-Year-Old Rookie” were part of his name.

Born May 6, 1939 in nearby Fall River, Massachusetts, Russ grew up a Red Sox fan (he was briefly a Boston Braves fan but before they left for Milwaukee when Russ was 13 years old.) His family was of English-Irish stock and was working class. His father was a factory foreman for a jewelry manufacturer and his mother was a factory worker for an office supply company. Russ was the middle of three brothers. Brother Jim was four years older and went on to a long career with IBM. His brother Paul, four years younger, attended MIT and is now a professor at nearby University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth.

At Fall River’s Durfee High School, Russ was a three sport all-star, as quarterback and co-captain of the football team, a starting guard for three years in basketball (winning the New England Championship as a junior), and, of course, he was all-everything in baseball.

He was offered a baseball scholarship to Rollins College in Florida, and football scholarships to Boston University, Boston College, and Holy Cross as a punter, but soon after graduating from high school in June of 1957, the 18-year-old chose baseball as the most likely way to a professional career. The football offers were aided by his three sport Durfee coach, Luke Urban, who after an all-American career at Boston College played briefly in the NFL as well as catching for the Boston Braves in the late 1920s.

It was while in high school that Russ had his first experience with professional sports. In his freshman year Russ entered a polio fundraiser sponsored by the Boston Celtics where for a quarter one could take 25 foul shots. Russ made 23 of 25 and won the first prize, a road trip with the Celtics. He thoroughly enjoyed his trip to Madison Sqaure Garden sitting on the bench with Bill Sharman and Bob Cousy.

Gibson’s talents were brought to the attention of the Red Sox by Jumping Joe Dugan, a local “bird dog” of considerable baseball fame, a 14-year major league veteran. Dugan told farm director Neil Mahoney about Gibson’s potential, and Mahoney eventually signed Gibson to a contract.

The Red Sox were not the only team interested in Gibson. The New York Giants checked Russ out when he visited the Polo Grounds as a Hearst All-Star. The annual tournament for high school seniors was run by Giants legend Carl Hubbell, and used by the Giants as a tryout camp. While Russ was in New York, his father summoned his son home because the Red Sox were preparing to make an offer. Due to the restrictive signing bonus rules of the times, Boston was not going to sign him to a bonus. That would require them to keep him on the roster and leave him sitting on the bench far too much. The Red Sox chose instead to sweeten the signing by offering to buy his parents a new car — a particularly tempting offer because the Gibson family car had died on the way to the contract discussions. To avoid invoking the bonus rule, the Red Sox instructed Russ’s father to pick out a car and let the team know how much it would cost; soon his father received a check for the full amount drawn on the Yawkey Construction Company.

Immediately after signing, the 18-year-old prepared for his first minor league assignment. Before he left, but not before his father arranged for Russ to talk with another Fall River local, Joe Andrews, who had made it as high as Triple A. Andrews was candid in telling Gibson what to expect and what was expected of him.

Right from the start, Gibson learned that both politics and business play a major part in baseball. In his first assignment, for Corning, New York, in the NY-Penn League, he appeared in only two games (he went 4-for-9) before he was summoned from his rooming house and told he was being shipped to Lafayette, Indiana, of the Midwest League. The move to Lafayette allowed him to play more or less regularly and in 41 games he batted a solid .312. His timely hitting produced 26 RBIs with 43 hits. Both the NYP League and Midwest Leagues were Class D, and Gibson’s change could be considered a promotion.

The next season, 1958, found Gibson again in the Midwest League, this time for Waterloo, Iowa. He was the everyday catcher (102 games), but he suffered somewhat of a sophomore slump as his average fell to .254. Two successful seasons in the Midwest League earned him promotion to the Class-B Carolina League, where he would spend the next three seasons. The first two were spent at Raleigh, where he played in over 80 games each year and hit .268 and .299. While at Raleigh he had the opportunity to catch the premier professional offerings of future Red Sox Hall of Famer Dick Radatz. Fresh off the campus of Michigan State, Radatz had a blazing, moving fastball that was nearly unhittable. In his first appearance, he was mowing them down but eventually a couple of batters caught up to him and singled. Gibson thought it was time to give the hitters another look so he signaled for Radatz’s curve. After being shaken off a couple of times, Russ went to the mound to personally ask for the curve. Radatz replied that he didn’t have a curve, so they stayed with the heater. (1) This “strategy” proved effective as the “Monster” went on to become baseball’s best reliever for a few years in the early 1960s. Although Gibson and Radatz never played together in the majors, they remained friends until Dick’s death.

After hitting .299 in 1960 and playing well in spring training 1961, Gibson felt he had earned and deserved a promotion, at least to Triple A, but it was not to be. In April he was sent back to the Carolina League, assigned to the new Red Sox affiliate at Winston-Salem. Once again, politics came in to play as the front office was “loading” the new franchise to boost attendance in its inaugural season. Gibson’s disappointment turned to discouragement and he has admitted that he didn’t put forth a strong enough effort when he reported to Winston-Salem. Well into the season, he was just going through the motions and was batting well below .200. It took a visit from Red Sox roving trouble shooter Charlie Wagner to show Gibson that he was only hurting himself. Broadway Charlie encouraged Russ to buck up, and he did.

Playing hard every day, by season’s end he had raised his average to a respectable .275, hitting 11 homers and driving in 71 runs in 110 games. This turnaround, coupled with an attitude adjustment, brought about a promotion for 1962, although only to York, Pennsylvania, of the Class-A Eastern League. Although it was not a Triple-A club, Gibson felt that this league was of a very high caliber. He had a good year even though his average dipped to .260. He showed some power with 37 extra base hits, including a career high 24 doubles.

In 1963, after six years in professional baseball, Gibson finally was promoted to Triple-A, and he remained at that level for the next four seasons. His first two Triple-A seasons he played for the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League. He appeared in just 80 games in 1963, and his average slipped below .250 for the first time (.244). Although he didn’t have a great year on the field, off the field he felt he had a very good year. In May he met a pretty young California native who was working as a secretary for the Boeing Corporation and by the next New Year’s Eve she had become Virgie Ann Gibson. Married life obviously agreed with Russ, because the next season saw him raise his average to .276, achieving career highs in game played (130), hits (129), and home runs (17).

Gibson’s manager at Seattle in 1963 was another Red Sox legend, Mel Parnell, whom he liked a great deal but felt was too nice a guy to be a manager. In 1965, the Red Sox moved their Triple-A affiliation to Toronto, and hired Dick Williams as the manager. Williams was anything but “too nice a guy to manage.” Gibson’s suffered through some injuries his first year under Williams, and he struggled, hitting only .215. However, he rebounded in 1966 to hit a healthy .292 and make a significant contribution to Toronto’s championship season. The latter season, he served as a player/coach and teamed with future fellow Red Sox rookies Mike Andrews and Reggie Smith, and 1967 teammate Jerry Stephenson.

At the end of Toronto’s season, Williams asked Gibson to join him for winter ball in Puerto Rico. Russ had played twice in Puerto Rico and enjoyed it; the money was good, too. As it turned out, though, Williams was unable to join him in Puerto Rico because immediately after the Red Sox season ended, the Boston front office tapped him to be the new manager of the Boston team. Even though his former manager was now the big league boss, that hardly guaranteed Gibson a slot for 1967. With Dick Williams one had to work hard to earn a place on the roster.

Still sharp from winter ball, Russ had a fine spring training in Winter Haven. Competing with the two catchers who had shared backstop duties for the ’66 Red Sox, Mike Ryan and Bob Tillman, Gibson proved himself major league worthy. He easily outhit Ryan (.261 to .185) and, although Tillman hit an uncharacteristic .344, Gibson’s hits were more timely, producing 12 RBIs to Tillman’s four. In his last spring appearance, Gibson’s three-run homer won the game for the Red Sox, assuring the team a winning Grapefruit League record, a distinction Boston had not achieved in several seasons.

As Russ headed for Boston, his dream had finally come true. After 10 long years in the minors, the Fall River kid was now playing for the Boston Red Sox. As the Red Sox bused their way to New York for a three-game series, Russ quipped that after riding buses for ten years in the minors, he was now in the majors and still riding a bus. His major league debut will always be remembered because it was also the debut of another rookie, lefty Billy Rohr, who came within one strike of pitching a no-hitter in his first major league game. Suffice it to say that Russ called a great game and handled both his own nervousness and that of his fellow rookie like a seasoned veteran. He was the first to reach Rohr when he was hit by a batted ball and helped persuade Williams to leave the pitcher in.

At the plate Gibson went 2-for-4. He was put out his first two times up against Whitey Ford, before singling off Ford in the sixth and Thad Tillotson in the eighth. He still marvels that the catch Yastrzemski made in the in the ninth inning to briefly keep Rohr’s no-hitter alive is the best catch he ever saw (a sentiment shared by others who saw it). He also asserts to this day that, with Rohr needing just one strike to close the game, the umpire blew the call on a 2-2 pitch to Elston Howard: “It was right down the middle.” However, visiting rookies don’t get the benefit versus a hometown veteran, so Howard lived to single off Rohr’s curve.

For the rest of April, Gibson served as the regular catcher, significantly contributing to the team’s 8-6 record, batting .300 with eight RBIs. But with Dick Williams, it’s what have you done for me lately, and after a mini-slump (eight hitless at-bats over three games), Gibson was replaced by Bob Tillman. Gibson then developed a hand infection; unable to play, he was optioned to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, (Eastern League) on May 10, when the roster had to be reduced to the 25-man limit. The move to Pittsfield was just temporary and he played only once to make it official. Returning to Boston, he again shared time with Ryan and Tillman.

One of Gibson’s favorite memories of 1967 involved “Russ Gibson Day” on July 30, organized by a number of his Fall River fans and friends. When it was first announced, Russ took some kidding from the veterans; Yaz said he had played for seven years and had won a batting title and had never had a “day” while here was Gibson, a rookie barely hitting .200 and he was getting one. In the days before the scheduled event Gibson had found himself in manager Williams’ often-filled doghouse and hadn’t been playing. However the night before his “day,” Williams approached Gibson and told him not to worry because he was going to start. Gibson shrugged and replied that if anyone should be worried if he didn’t start on Sunday it should be Williams himself. Russ didn’t disappoint the 45 buses and more than 200 private cars that brought his fans to Fenway. He went 2-for-4 with two doubles, but the Sox lost to the Twins, 7-5.

Soon after the “day,” another roster move took Russ back to Pittsfield. During this sojourn he played in 18 games and achieved what he hadn’t in his first major league game: catching a no-hitter. The hurler for Pittsfield was Bob Guindon, who had been all-everything as a high school first baseman at Boston English and had signed with the Red Sox for a substantial bonus. An off-season accident to his hand had limited his hitting so he was in Pittsfield attempting to make a comeback as a pitcher. By coincidence, the Gibsons were renting the Guindons’ Needham home during the 1967 season.

Gibson was back on the Red Sox roster with the September call-ups. By this time, veteran Elston Howard had been acquired from the Yankees and Bob Tillman had been sold to New York. For most of the September pennant race, Gibson played sparingly, with Howard and Ryan doing most of the catching. In the crucial final weekend series versus the Minnesota Twins, however, Dick Williams looked to the catcher who had helped him win it all the year before in Toronto. Gibson started both games, though he was pinch hit for early in each contest. The Red Sox won each game, and took the pennant on the final day. In his rookie season, Gibson hit .203 in 49 games.

It appeared that Russ might not be eligible for the World Series, because he had not been on the roster just before the September 1 deadline, but the Cardinals allowed the Sox to add him to replace the injured Bill Landis. Against St. Louis, Gibson started Game One and was involved in two crucial plays, both of which he claims involved blown calls by umpires. The first call went his way. In the fourth inning, he took a Yaz throw and tagged out Julian Javier trying to score from second on a single. Russ claims, and Danny Gostigan photos published in the Globe the next day bear him out, that although he tagged Javier with his glove he had the ball in his other hand. The other missed call was much more important to the game’s outcome. In the seventh inning, Lou Brock attempted a steal of second. Gibson made a perfect throw to Rico Petrocelli, beating Brock to the bag — but the umpire ruled the legendary base stealer safe. Brock eventually scored on Roger Maris’s grounder. It turned out to be the margin of victory in the 2-1 game. For the rest of the Series, Williams went with the post-season experienced Howard. Gibson’s only other Series appearance was in Game Seven as a late-inning defensive replacement.

Although 1967 will always be remembered as the high point of his Red Sox career, Gibson played two more years with his hometown team. In 1968, he and Howard shared the catching duties. Mike Ryan had been dealt to the Phillies in the off-season. Neither catcher excelled at the plate in this “year of the pitcher.” Howard in his last year batted .241 with five home runs and 18 RBIs, while Gibson raised his average to .225 with three home runs and 20 RBIs.

In 1969, Gibson had his best year statistically. He lifted his batting average to .251, with three homers and 27 RBIs. Appearing in only 85 games, he was backed up behind the plate by rookie Gerry Moses (.304 in 53 games) and Tom Satriano, acquired in midseason.

Even though Gibson was coming off his best year in the majors and had a good spring in 1970, the Eddie Kasko-led Sox chose to go with Moses and Satriano. Gibson credits GM Dick O’Connell with finding him a good place to go: O’Connell called San Francisco Giants owner Horace Stoneham and secured a place for Gibson.

How do we know which came first? Could it be that the manager reduced his playing time because he was hitting .232 or .193? Also Dick Dietz, the Giants regular catcher hit .300 and drove in 107 runs in 1970. He saw limited duty in San Francisco, backing up Dick Dietz. In his three years with the Giants his average dipped with his playing time. In 1970 he appeared in 25 games, hitting .232 in 69 at-bats; in 1971 in 25 games with only 57 at-bats he hit .193 and didn’t appear in the Giants playoff loss; and in 1972 he spent most of the year in Triple-A Phoenix, hitting just .167 in five games and only 12 at-bats for the big club. Although he didn’t play much, Gibson enjoyed being on the Giants with the likes of Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Bobby Bonds and catching future Hall of Famers Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry. Although offered a contract and invited to spring training by the Giants in 1973, Russ decided to officially retire.

Gibson had played in the major leagues long enough to qualify for a pension. Wisely, he had also prepared himself for life after baseball. Through connections made in San Francisco, he landed a good position with Bank of America on the West Coast which he held for almost 10 years before he returned to the Fall River area. For the next 20 years, Gibson worked for the Massachusetts State Lottery covering the Fall River/New Bedford area.

While working for the Lottery, he was able to return to baseball activity part time. For two years he was head coach of a local junior college nine, Bristol Community College. He also spent some time as a local area scout for the Chicago White Sox, thanks to one of his former Red Sox teammates. Soon after Ken Harrelson was named White Sox general manager, he called Russ to offer him a job in the organization. Not willing to give up his steady Lottery position, he agreed only to accept a part-time scouting job. This was another good decision, as Harrelson’s tenure as White Sox GM was brief. After his scouting days, Gibson’s baseball activities included his regular participation in Red Sox fantasy camps organized by his old friend Dick Radatz. Age and health concerns later limited his activity to an occasional Jimmy Fund golf tournament.

On the home front, Russ and Virgie Ann Gibson had a most successful marriage for 27 years until her death in 1990. Together they raised two boys, Gregg and Chris, both of whom lived in the area allowing Russ to enjoy them and his three grandchildren on a regular basis. Gregg attended Worcester Polytechnic Institute, where he joined Air Force ROTC. After flying for the Air Force, he spent some time with United Airlines and is now a corporate pilot. Chris was located even closer, serving as a police officer in the neighboring town of Somerset.

As he approached his 50th high school reunion and the 40th anniversary of that “Impossible Dream” season, Russ Gibson was able to look back at his life and say he had no regrets. After a long illness, Gibson died on July 27, 2008, in Swansea, Massachusetts.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium On The Field, edited by Bill Nowlin, and published by Rounder Books in 2007.

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia, 9th Edition. Macmillan: New York, 1993

Boston Globe (Morning, Evening, and Sunday). March 1967-October 1967.

Coleman, Ken, and Dan Valenti. The Impossible Dream Remembered. Stephen Greene, 1987.

Crehan, Herbert F. (with James W. Ryan). Lightning in a Bottle. Branden, 1992.

Crehan, Herb. Red Sox Heroes of Yesteryear. Rounder, 2005.

Frommer, Harvey. Where Have All Our Red Sox Gone. Taylor Trade, 2006.

Interview with Russ Gibson conducted by Thomas Harkins and Robert Payer on Saturday, March 25, 2006, in Somerset (MA).

McSweeny, Bill The Impossible Dream. Coward-McCann, 1968.

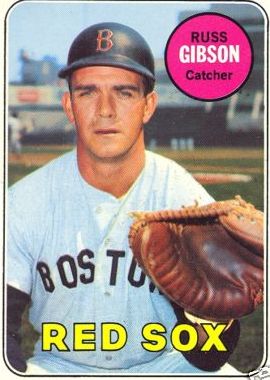

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

John Russell Gibson

Born

May 6, 1939 at Fall River, MA (USA)

Died

July 27, 2008 at Swansea, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.