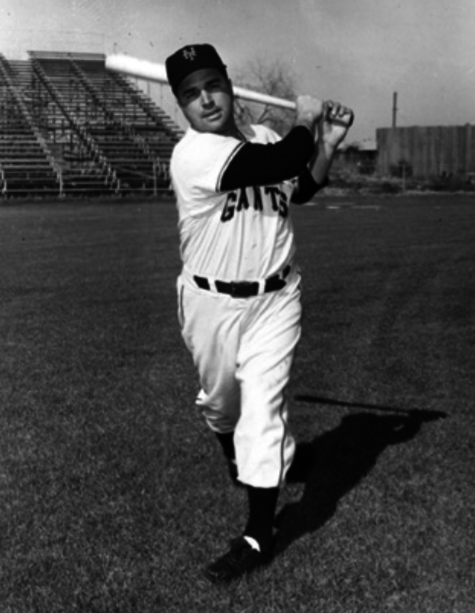

Sal Yvars

If not for a spectacular catch by Hank Bauer in the ninth inning of the sixth and final game of the 1951 World Series, Sal Yvars might be remembered quite differently today. Yvars’ only appearance in a Series at first looked like the stuff of legend. He struck a ball deep into the outfield of Yankee Stadium as twilight was beginning to fall. It looked like a sure hit that would plate a run and tie the game. It was the kind of hit that can alter a team’s momentum, and perhaps change the course of a World Series itself. The sold-out Yankee Stadium crowd of 61,711 braced itself for the sure hit. Somehow, sliding and diving, Bauer just managed to nab the ball, ending the Giants’ threat and terminating the Series. With that miraculous catch, the Yankees became world champions and the Giants’ improbable 1951 season came to an end. Such are the vagaries of baseball.

If not for a spectacular catch by Hank Bauer in the ninth inning of the sixth and final game of the 1951 World Series, Sal Yvars might be remembered quite differently today. Yvars’ only appearance in a Series at first looked like the stuff of legend. He struck a ball deep into the outfield of Yankee Stadium as twilight was beginning to fall. It looked like a sure hit that would plate a run and tie the game. It was the kind of hit that can alter a team’s momentum, and perhaps change the course of a World Series itself. The sold-out Yankee Stadium crowd of 61,711 braced itself for the sure hit. Somehow, sliding and diving, Bauer just managed to nab the ball, ending the Giants’ threat and terminating the Series. With that miraculous catch, the Yankees became world champions and the Giants’ improbable 1951 season came to an end. Such are the vagaries of baseball.

Instead Sal Yvars is chiefly remembered for his key role in the Giants’ complex sign-stealing operation of that same season. But that is the end of the story. Yvars’ story begins with his parents, Joaquin and Lena, Spanish immigrants. The family name was Ivars until it was mangled at Ellis Island. They lived in genial squalor in Manhattan where Sal, the oldest of three sons, was born on February 20, 1924. When he was 6 months old, the family of four (Sal had an older sister, Theresa) moved to the Valhalla section of White Plains, New York. Like much of America at the time there was stark division between the income levels. The family lived in the poor side of town. They had no indoor plumbing. Like so many immigrant families the Yvars family had an outstanding work ethic and an innate desire to improve themselves. Yvars’ mother worked in a laundry and his father worked as a grave digger at the local cemetery. For the princely sum of $14 a week, he wore out his back.

The poverty the family had known in New York City was not greatly eased by a more suburban existence. For fuel, Sal combed the local railroad line for cast-off coal. On occasion the struggling family pilfered branches from the local trees. They bathed in the local reservoir.

When he was old enough, Sal worked for a local nursery, digging, just like his father. But where the father planted the dead, the son planted flowers and shrubs. To supplement this income, he caddied at a local golf club. Like virtually every kid in America at that time Sal was drawn to sandlot ball whenever he got a moment of free time. Unable to afford a glove, he still performed admirably at shortstop, becoming hot stuff at a very early age.

Sal’s first established games under formal rules occurred in school. In high school he was a three-sport star. At basketball and football, he was talented but his best sport by far was baseball. By high school he had been shifted to catcher, where he regularly hit over .400. It was also at this time that Sal’s notorious short temper began to assert itself. One day a classmate insulted him by roasting him with a racial epithet. Sal struck back with his fists and promptly quit both the team and school to help support his family.

Sal was too good an athlete for his small high school to lose, however, so the powers that be in his little town turned the truant into a professional. In exchange for returning to school, an anonymous benefactor left $12 at the local drugstore for him each week. Sal turned the envelopes containing the money to his mother. No one, not Sal, not the school, not his parents, not anyone who knew anything said anything about it. Perhaps it was here that Sal first learned how to keep secrets so well.

Yvars distinguished himself in high school and expected a college scholarship. None turned up and then he discovered that he was one credit short of graduating. His coach pointed out that if Sal just happened to fail a course, he would have to repeat the grade and would have another year of playing eligibility and thus another chance to perhaps win that college scholarship. No fool, Sal chose to fail geography with distinction.

But after another spectacular year of play, a scholarship still did not appear. Giants scout Nick Shinkoff, however, liked what he saw. In 1942 Yvars had been the MVP of the local semipro team, hitting well over .500 in 14 games. Shinkoff signed him and he was assigned to the Class D Salisbury (North Carolina) Giants for $85 a month, a veritable fortune in the eyes of Sal and his family. The young star was obviously thrilled but it never came to pass. World War II intervened. Sal was 19, in fantastic physical shape, and believed he was sure to be drafted. One year to the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the Army Air Force with hopes of being a fighter pilot.

Yvars’ eyes were not quite up to fighter-pilot caliber, however, so he did the next best thing; he became a test dummy stand-in for the real flyboys. He rode G-force sleds and tested equipment like helmets to see what effect they would have in real-world situations. Among his more remarkable feats was pulling six G’s without a helmet. That stunt landed him in the hospital for three days. When not exposing his body to the threats of nature, Yvars played and coached baseball in a unit team. He was never sent overseas and spent all of the war in South Carolina and other Southern states. On his service teams Yvars rotated between catcher and shortstop. As a star athlete, he got away with things that other soldiers simply could not. One day he punched a sergeant for not showing enthusiasm for jumping jacks. Other enlisted men might have felt the wrath of a court-martial. The punch did not affect Yvars in the least; he left the service in 1946 with an honorable discharge.

Yvars’ play in the service and a fawning letter from his high-school coach prompted the Giants to start him at a higher level after the war. They assigned him in 1946 to the Manchester (New Hampshire) Giants of the Class B New England League. By now, the 5-foot-10 right-hander with the stocky build was a natural at catcher, which became his regular position. Once in Organized Baseball, Yvars lived up to his hype: 220 at-bats, 8 home runs, and a .318 batting average. Things were going well until Sal’s temper flared once more. In June he decked both the manager of the Nashua Dodgers, Walter Alston, and his own manager, Hal Gruber. Yvars received a ten-day suspension; a lesser athlete might have been given a train ticket home.

Because of his obvious gifts the Giants moved Yvara up to Triple-A Jersey City the following season. The Little Giants’ catcher Mickey Grasso, who had been with the parent club the previous season, was slumping in midseason. The team was 14 games behind the Montreal Royals when on July 27, 1947, Jersey City manager Bruno Betzel decided to insert Yvars as the starting catcher. It was just what the stumbling team needed. With Yvars in the lineup, the team won 56 of its remaining 76 games, clinching the pennant on the last day of the season with a 5-3 win over the Baltimore Orioles. For the season, Yvars hit a solid .293 in 80 games.

Yvars’ performance had not gone unnoticed by the Giants, and on September 27, 1947, he sipped his first cup of coffee in the majors. Before 2,964 chilly Phillies fans in Shibe Park, he had a mediocre debut with one hit and two strikeouts in five at-bats in his only big-league appearance of the year. The next day, back in White Plains, Sal married Antoinette, his high-school sweetheart. The marriage lasted until the end of his days.

Yvars’ brief taste of “The Show” gave him a desire for more. He diligently applied himself in 1948, playing with distinction for Jersey City once again. As the club’s regular catcher, he hit .301 with 16 home runs and 88 RBIs. The Giants beckoned again near the end of the 1948 season, and Yvars hit.211 in 42 plate appearances, including a home run off Lou Possehl.

Yvars’ career altered course sharply during spring training in 1949. During a meaningless game for charity, Giants manager Leo Durocher was all over Sal for not arguing balls and strikes. After Sal left the game with an injury, he and Durocher engaged in a heated argument. Surprisingly, considering the tempers of the two men, the dispute did not result in fisticuffs, primarily because Giants players and coaches intervened. Even so, Yvars had tossed one of his shin guards at his manager’s head

To no one’s great surprise, that night the team secretary phoned Yvars and informed him that a ticket home was waiting for him. For reasons unknown, however, Leo Durocher had a change of heart and gave him a second chance. The second chance seemed more of a punishment as Yvars sat day after day as the bullpen catcher. Things looked dim, but salvation came, as it so often had before in his life, in the form of chicanery.

During a spring-training game against the Cleveland Indians, Yvars noticed that the Indians catcher was tipping his signals. Word got back to Durocher and the Giants responded like a team possessed. Against some of the best pitching in the major leagues, the Giants scored 54 runs during one homestand. Too bad it was only spring training.

Despite his good deeds in spring training, Sal was assigned to the Minneapolis Millers of the Triple-A American Association. It was not a good fit. Yvars’ quick and violent temper kept him in hot water for as long as he was with the club. His lowlight reel included leaping into the stands and loosening the teeth of a heckler, and multiple fines for arguing with and insulting umpires. His relationship with his manager, Tom Heath, was so poisonous that Yvars ended up being kicked up to the big-league team to allow everyone to cool off. He did, however, bat .307 with 57 RBIs for the Millers in 84 games. With the big-league club, Yvars went hitless in three games.

The next year, 1950, found Yvars back in Jersey City, where he batted .282 with 8 home runs in 91 games, and fielded respectably. That performance earned him a late season call-up to the Giants, where hit .143 in nine games. In 1951 Yvars became the Giants’ third-string catcher, exiled to the bullpen to warm up relievers and keep starters loose. Glorious it was not, but the $7,500 major-league salary made every moment out of the limelight worth it. Yvars spent the entire season with New York, but appeared in only 25 games, batting a lusty .317 in 50 plate appearances.

Yvars’ relationship with Durocher had not been improved by time. The two men were best described as frosty acquaintances. They rarely spoke to each other and Durocher scarcely hid his contempt for the stocky Spaniard. He made it clear to Sal that the only reason he was in the majors was his skill at stealing signs. Yvars toiled away in the bullpen, starting 12 games as Durocher tried to see if he was a good fit for any of the team’s pitchers. Durocher discovered that Sal had just the right temperament to be Sal Maglie’s regular catcher.

Once the Giants’ complicated sign-stealing system was instituted on July 20, Yvars became an integral part of the process. From his position in the bullpen, he would either hold up a baseball, indicating a fastball, or, if he tossed the ball in the air, it meant breaking stuff. Many of the Giants’ batters came to rely upon Yvars, and the team enjoyed one of the most fabled comebacks in all of sports history.

After going public with the story in the 1990s, Yvars steadfastly maintained that he flashed Bobby Thomson the signal for fastball in the pivotal game. Just as adamantly, Thomson maintained that he never saw or even looked for the signal, although he had admitted to the Giants’ sign-stealing operation.

Whether all that effort is what turned the tide for the Giants remains a source of controversy. Dave Smith of Retrosheet performed a game-by-game analysis of the Giants’ 1951 season. “New York went 51-8 after they began stealing signs (including going 24-6 at the Polo Grounds), (but) the Giants actually hit worse at home after that point than before,” Smith said. “On the morning of July 20 – the day the scheme went into effect – the Giants were batting .263 at home and .252 on the road. For the rest of the season New York hit .256 at the Polo Grounds and .269 away. Conversely, before July 20, the Giants pitching staff had a 3.44 ERA at home and 3.53 on the road; after July 20 their ERA was 2.80 at home and 3.05 away.”1

Smith is convinced that the Giants did not benefit from the system in any measurable way, as the team did not begin to catch fire until August 12. Whatever the case, books about Yvars’ role in the sign-stealing scheme brought him renewed fame in his twilight years and greatly eased his nagging conscience.

Despite Yvars’ one at-bat in the World Series being an out, it was the unquestioned high point of his career. He then remained with the Giants through the 1953 season. The most games he played in during a season was 66 in 1952, when he hit .245 while trying to keep his famous temper intact. One of his run-ins came in that most busy 1952 season with Earl Torgeson,

As Mark Armour wrote, “In the bottom of the first on July 1, 1952, at Braves Field, Torgeson’s backswing hit Giants’ catcher Sal Yvars on the shinguard. After Torgeson lined a single up the middle, Yvars picked up the bat and slammed the handle on the plate, shattering it. Torgeson was stranded on the bases, so he did not return to the Braves dugout until after the Giants were retired in the top of the second. When he discovered the broken bat, Torgeson removed his glasses, then sprinted across the field to the Giants’ dugout and slugged Yvars in the face, leaving the catcher’s right eye swollen, discolored, and bloody. “Sal and I always have been good friends. But breaking a guy’s bat is like slapping him in the face,” Torgeson said after this incident. “We may be in seventh place but we don’t have to take that insult.” Torgy was fined $100 for the fight, Yvars $25. The good friends brawled again on July 18‚ 1954, after both players had changed teams.”2

On June 15, 1953, Yvars was sold to the St. Louis Cardinals for $12,500. The most remarkable thing about his time in the Gateway City was how similar his two seasons were. In both 1953 and 1954 seasons he had exactly 57 at-bats, 14 hits, and identical batting averages of .246. Every other category stood only a hairs-breadth difference over the two seasons. Yvars’ final major-league game came in a St. Louis uniform on September 26, 1954, eight years after his career had begun. He was 30 years old and running out of time and talent. Playing the Milwaukee Braves in Milwaukee’s County Stadium, the Cardinals won, 2-0 in 11 innings. Making the most of his last day, Yvars scored the first of those runs after reaching first on an error; he came home on Wally Moon’s home run.

Technically Yvars ended his playing career as a member of the Detroit Tigers. On December 3, 1954, the Cardinals sent him to Detroit in exchange for outfielder Frank Carswell. Neither ever played for the teams they were traded to. Carswell never again played in the majors after his 16 games with Detroit. As for Yvars, he was released in June 1954 without playing for the Tigers. He returned to the minors in 1955 to try to win a place with the Tigers. In 15 games for the woeful (52-102) Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association, he hit.333 and was rewarded in midseason with a spot on the Buffalo Bisons of the International League, but played in only nine games, batting .278. An oddity of his time in Buffalo is that he served with Tom Yewcic, making baseball’s first and last team to have two catchers whose surnames began with Y. Playing for Buffalo must have been an odd experience for Sal. When he had been with Jersey City, Buffalo fans took delight in riding Yvars and hung the epithet “Soggy Sal” upon him. He was released after the season.

Yvars returned to suburban Valhalla, to the home he had bought with his first season’s earnings. The home was his residence for the rest of his life. He worked as an investment broker for 50 years before retiring in 2005. He and Antoinette had four children, five grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Even before his retirement, Sal enjoyed working on his yard, observing birds and golfing with the intensity and competitiveness that he had played baseball. He did extensive charity work and was a raconteur on the banquet circuit. In 2006 Yvars was diagnosed with amyloidosis of the heart, a rare disorder in which amyloid proteins attack the body’s organs. He died on December 10, 2008, aged 84, and was buried in Cemetery of the Gate of Heaven in Hawthorne, New York.

The first of the Giants to really expose the 1951 sign-stealing system, Yvars took delight in being proved correct by investigators. It greatly eased his guilty conscience, and his final years, aside from his battle with disease, were very happy indeed.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Sources

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thompson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

Miami News, June 8, 1952, .6.

Diehl, John, “Sal Yvars – Never Meant to Be a Hero” Baseball Digest, October 1961, 47-49.

Goldstein, Richard, “Sal Yvars, 84, Dies; Revealed Baseball Scheme,” New York Times, December 11, 2008.

Thompson, Josh, “Former Major-Leaguer Yvars, Linked to Legendary Home Run, Dies 84,” The Journal News (White Plains, New York), December 11, 2008.

Baseball Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_XYZ/Yvars.Sal.Obit.html

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, The Hidden Language of Baseball: How Signs and Sign Stealing Have Influenced Our National Pastime (New York: Walker Publishing Company, 2003), 146.

2 Mark Armour, “Earl Torgeson,” SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/25b3c73f.

Full Name

Salvador Anthony Yvars

Born

February 20, 1924 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

December 10, 2008 at Valhalla, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.