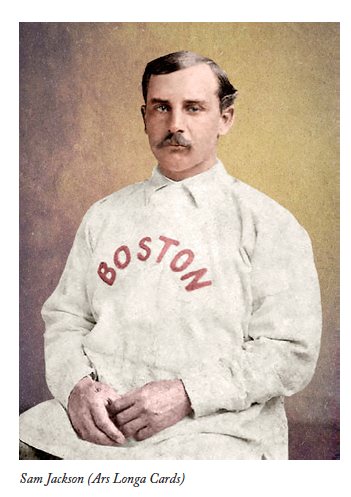

Sam Jackson

Of the 22 men who played for the Boston Red Stockings over the five years from 1871 through 1875, 17 were American-born and the other five were born in other countries. There was one Canadian, one Irishman, and three from England. George Hall (Stepney) and Harry Wright (Sheffield) were both English natives. So was Samuel Jackson.

Of the 22 men who played for the Boston Red Stockings over the five years from 1871 through 1875, 17 were American-born and the other five were born in other countries. There was one Canadian, one Irishman, and three from England. George Hall (Stepney) and Harry Wright (Sheffield) were both English natives. So was Samuel Jackson.

Jackson was born on March 24, 1849, in Ripon, Harrogate Borough, North Yorkshire West Riding, England. The actual birth register confirms that he had no middle name. His parents were John Jackson, who milled corn for a living, and Jane Jackson. At the time of the census of England in 1851, they had four children, all boys, of whom Samuel was the youngest. They lived with John’s widowed mother, Mary, and had a 19-year-old servant from Leeds, Harriet Place.

In 1853 the family immigrated to the United States, but seemed to live near the border with Canada. Their fifth child, Mary, was born in 1855, in Canada.

Rochester, New York, baseball historian Priscilla Astifan reports, “Sam Jackson first appears in the baseball accounts in 1865, at the apparent age of 15, playing with the Pacifics. He continued to play with them in 1866 and then played with the Alerts, a significant junior team, in 1867 through 1869. Jackson helped his teammates achieve one of the best scores against the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings on their historic tour which included a stop in Rochester on June 4. Sam’s brother William played right field on the same Alerts team, while Sam played first base. The Alerts, including Jackson, played against the Cincinnati Red Stockings another time that year when they made a western tour which included Cincinnati. In 1870 Jackson again played here with the Flower City, a consolidation team.”1

Sam Jackson was 22 when he first played for the Boston Red Stockings. When Boston “finally determined to secure a base ball club second to none in the country… Mr. Adams, the proprietor of a hotel in that city,” approached George Wright in 1870. Wright, unable to come to terms with the Cincinnati Red Stockings, responded to Adams’s interest, signed on, and began to recruit players. George and Harry Wright, Charlie Gould, and Cal McVey were said to be “the nucleus of the Boston nine,” with Ross Barnes, Al Spalding, and Fred Cone – all from the Rockford, Illinois, Forest City club – “three of the best players in the Western country.” The seven were supplemented by Harry Schafer and Samuel Jackson, described by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette as “a No. 1 player in all respects.”2

Red Stockings president Ivers W. Adams had described Jackson to fellow stockholders in the Boston Base-Ball Association as “a young and comparatively unknown player, but one whose record as an amateur has been a good one both as a player and a gentleman, and gives promise of proficiency second to none, Samuel Jackson, from the Flower City club, of Rochester, New York.”3 The New York Tribune dubbed Jackson “a promising amateur of the Flour(sic) City Club of Rochester.”4

Manager Harry Wright wrote to Jackson, in Rochester, on January 9 urging him to report to Boston during the first week of March. “As your terms are satisfactory, you may consider yourself engaged,” he wrote, adding that his contract would be ready for him when he arrived in Boston but that in the meantime he was sending a few lines to Jackson that he wanted Jackson to countersign before announcing that he had been hired.5

Jackson’s first game in Boston was on Fast Day, April 6, 1871. He played right field and batted eighth against a picked nine in front of 5,000 spectators at the team’s home field, the Union Grounds. The Red Stockings won, 41-10. Jackson scored seven runs, the most on the team. Some other games were played in Cambridge, and against the Harvard club at the Union Grounds, in April. Jackson tripled in the first inning in the April 26 game, and doubled in the fifth.

He made his regular-season debut on May 9, at Troy against the Troy Haymakers. He had himself quite a day, taking over for George Wright at shortstop after both Wright and Fred Cone collided going after a fly ball to left. Wright’s leg was injured so badly he had to leave, transported by carriage to the hotel. Both Wright and Jackson had three at-bats, and each was 2-for-3. Both of Jackson’s hits were for extra bases, a double and a triple, and he drove in two runs as Boston beat Troy, 9-5. The Boston Journal said that Jackson “did the best batting of the game.”6

When the Red Stockings arrived back from Troy on May 10, a crowd of some 300 met them at the Boston and Albany railroad train depot in Boston. The whole team went on to the club’s headquarters at 18 Boylston Street, save for the Wrights. George’s leg could not bear weight, so Charlie Gould and Fred Cone carried him to another carriage which transported him to brother Harry’s home. The rest of the team enjoyed a dinner at the Parker House.7

Wright didn’t come back until June 17, and just for that one game. Ross Barnes took over most of the work at shortstop.

Jackson’s next game was a full week later, against Troy in Boston. He batted ninth, played center field, and was 1-for-4 with a first-inning RBI. On May 24 the Olympics of Washington came to Boston. This time Jackson led off, playing second base. He was 0-for-5 and committed his second error of the season. The game ended in a 4-4 tie.

Asa Brainard may have had his number; Jackson was 0-for-4 in a rematch with Brainard and the Olympics on May 27.

The Rockford Forest Citys came to Boston on May 29 and got hammered, 25-11. Jackson was again playing second base and leading off. He was 4-for-7, with a double and a triple, an RBI, and three runs scored. Three days later the two teams played again on Decoration Day; though Jackson was 0-for-5, he got on base and scored three times in Boston’s 11-10 win. Rockford committed eight errors.

In the June 2 game Jackson batted ninth. He was 2-for-4 with a double and an RBI in the second inning, but the Chicago White Stockings beat Boston, 16-14. He was 0-for-5 against Cleveland on June 14 and 0-for-4 against the Mutuals of New York on June 17, batting third. That said, Jackson was considered to be a threat. Describing the June 14 game, the New York Clipper correspondent wrote that Jackson had come to bat in the ninth inning, down by two runs: “Jackson to the bat amid much excitement, as he had not yet made a first base hit and as he has a peculiar faculty for saving games the crowd looked for something from him in that line.”8

Four days later, the Fort Wayne Kekiongas came to Boston. This time, Jackson was again in the middle of the order, batting fourth. He was 1-for-6 in the game, with another run batted in.

There was a nonchampionship game against Brown University on June 23, which the Red Stockings won, 24-3. Jackson scored three runs. (The two teams played again on June 30.) On the 26th Boston played Philadelphia at the Jefferson Street Grounds. Jackson was 1-for-5 with an RBI; the Athletics won, 20-8.

The team traveled north of the border for a nonscheduled game against the Resolutes of Hamilton, Ontario, on June 30. They won, 27-0.

On the Fourth of July in Washington, Boston beat the Olympics, 7-3. Jackson was 0-for-4 with two errors, and was also caught off base in the first inning – not for the first time in 1871. He was also 0-for-4 with another error, his 17th of the season, at Lake Park in Chicago on July 7. His average had dipped to .188.

He had a better day on July 10 in Rockford: 2-for-5 with an RBI.

The best day of Jackson’s career was his 4-for-7 game at Fort Wayne on July 12. He scored five times and drove in three; Boston won, 30-9.

The very next day, in Cleveland on July 13, he played his last championship game for the Red Stockings in 1871. He was 0-for-4 with an error.

After July 13, the team didn’t play another championship game until August 3. That’s the very day George Wright came back; Ross Barnes shifted over to second base.

Jackson, however, played at least one other game for the Red Stockings, working second base (with Barnes at short) on July 14 in Troy.

He had played in 16 games, batting .224, with 11 RBIs and 17 runs scored. He’d walked once and struck out four times (tied with Dave Birdsall for the most on the club), and had been caught stealing the one time he tried. He had five doubles and three triples. Jackson committed 18 errors in all, in the 14 games he played second base, and committed one at shortstop the one game he played there. The game he played in center field, he was error-free.

Though he was not in any more championship games in 1871, he hadn’t entirely left the club. He’s seen in an intramural match, playing second base for Harry Wright’s nine against Spalding’s nine, on August 1 at the Boston grounds. With only 11 players on the Red Stockings roster all season long, the teams were both supplemented by players from local amateur clubs. And on September 12, he played left field in a “practice game” in Boston against the Unas.9

The Chicago Inter Ocean acknowledged Jackson late in September, noting that Ross Barnes had taken over at second base and “Jackson has dropped out altogether.”10 The circumstances of his departure are unknown. It probably wasn’t due to his card-playing, but there’s a story he told a Buffalo newspaper. Harry Wright apparently “insisted that the players go to sleep at 10 P.M. One night, four of them were playing cards around midnight. When he called to them, the players, with their doors locked, did not respond. The next day they could tell from Wright’s looks that he knew they had been awake.”11 Jackson told the Buffalo Express, “After that, we utilized a light-proof curtain when we remained up after hours.”12

The Chicago Tribune foresaw Jackson working in 1872 as a reserve for the Brooklyn Atlantics.13 He was the left fielder for Brooklyn at the start of the season, playing in the inaugural contest against the Middletown (Connecticut) Mansfields on May 2. He went without a base hit in four at-bats, but was 2-for-4 the following day in Troy. On May 6 the Troy team paid a visit to Brooklyn’s Capitoline Grounds; Jackson played left field and swapped positions with John Kenney, taking over second base while Kenney went to left field. He was 0-for-3 and committed two errors on top of one he’d made on May 3.

Then the Boston Red Stockings came to town and beat Brooklyn 23-3. The Atlantics committed an astonishing 23 errors. Three of them were Jackson’s, and he’d only come in midway through the game to take over for Bob Ferguson at third base. He’d now made six errors in four games. That said, teammates Barlow, Burdock, Ferguson, and Remsen had all committed seven on more, and (despite neither team committing a recorded error in Brooklyn’s first game) the Atlantics had committed 52 errors in the succeeding three games. The Boston Journal succinctly observed, “The defeated Nine played very poorly throughout the game.”14

Jackson was hitless in his two at-bats on May 7; he was batting .167. He’d neither scored nor driven in a run, nor drawn a base on balls.

Less than a full calendar year after he’d begun playing, Jackson’s career came to an end. He appeared in only those first four games for Brooklyn. There was no reported injury. It may simply be that he didn’t measure up. The Atlantics didn’t do any better without him; they lost their next five games, too. There was quite a lot of reshuffling, dropping, and adding of Brooklyn players over the following month, and as late as August 5 the team had only won two championship games. Brooklyn cycled through 23 players in 1872 (the Boston Red Stockings only used 22 players in total from 1871 through 1875), but remarkably used just one pitcher all season long – Jim Britt. He started every game, and every start resulted in a complete game. Britt finished the season 9-28 (4.53 ERA). Fourteen Brooklyns played outfield at one time or another.

Jackson’s career in baseball had come to an end. A little over a month later, he is found operating a retail store in Guelph, Ontario, named Ryan’s Dead Ball Distributorship.15 He sold cigars and tobacco, but also “every description of Base Ball Supplies.” He proclaimed himself the sole agent in the Dominion of Canada for the Ryan dead ball, “the only ball used in the United States Championship games.” Jackson’s newspaper advertisement said that “Having played last Season with the Professional Red Stocking’s(sic), of Boston, feels satisfied that by his knowledge of the game and its requirements, he can meet the wants of all purchasers.”16

In 1873 Jackson married Mary Estelle Bell, a New York native born to a father from England and a mother from New York. Jacob Dunn Bell had been born in Liverpool in 1811. He arrived in New York as a teenager, in 1827. His wife, Hannah Sprague, was from New York. Jacob worked as a machinist in 1850 but was listed as a farmer in both the 1860 and 1880 censuses. The Bell family lived near Rochester.

At the time of the 1865 New York State census, John and Jane Jackson and their family lived in Rochester, too. John continued work as a miller. That was the trade Sam Jackson took up after baseball. He appears in the 1880 census living in Niagara, New York, with Mary and their three children, Mary (who became known as Minnie), Frank, and Laura. Twenty years later, they still lived in Niagara and Sam was still working as a miller. Daughter Mary was a teacher, living with them. A younger daughter, Laura, born around 1883, lived in the household as well. It was in 1900 that Samuel Jackson became a naturalized American citizen.

Ten years later the family had moved to Plainsville (now Gypsum), New York, near Gypsum Springs on the eastern edge of the Town of Manchester, some 25-30 miles southeast of Rochester. Sam purchased and worked at a grist mill. In January 1928 Sam’s wife, Mary, died. Sam and his daughter Mary were living in the same home at the time of the 1930 census.

Jackson’s grandson David VanGelder talked with Tim Munn in 2004 and said that “his grandfather was always a physical man right up to the time of his death. … David said he played catch with his elderly grandfather when an errant throw broke the front porch window. [David] thought he would be upset but to the contrary [Jackson] dismissed it with laughter. He described his grandfather as a person of tremendous work ethic – worked up to the day he died, a Mark Twain mustache and loved to smoke his pipe.”17

Not long afterward, Samuel Jackson died at home on August 4, 1930, at Clifton Springs, New York, just about five or six miles from Manchester. He is buried nearby at the Gypsum Cemetery in Gypsum, New York.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Jackson’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks for help on this article to Priscilla Astifan, and to Richard Astifan, Paul Batesel, Bob LeMoine, and Tim Munn. Thanks as well to genealogy research volunteer Barbara Hill, and to Wilma Hill, curator from the Ontario County Historical Society. And thanks to Craig Bacon, Deputy County Historian at the Niagara County Historical Society.

Notes

1 Emails to author from Priscilla Astifan, March 28 and June 10, 2016. From 1990 through 2002, Ms. Astifan produced a series of five booklets on “Baseball in the 19th Century” for the Rochester Public Library.

2 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, January 19, 1871: 2.

3 “The Boston Base-Ball Club,” Boston Journal, January 21, 1871: 1.

4 “Base-ball Nines for 1871,” New York Tribune, January 27, 1871: 3.

5 Letter from Harry Wright in Cincinnati to “Friend Jackson,” January 9, 1871. The letter is in the Samuel Jackson player file at the National Baseball hall of Fame.

6 “Base Ball at Troy, N.Y. – The Bostonians Defeat the Haymakers,” Boston Journal, May 10, 1871: 4.

7 “Boston and Vicinity,” Boston Journal, May 11, 1871: 4; “Base Ball at the Hub,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, May 14, 1871: 1.

8 “Cleveland vs. Boston,” New York Clipper, June 24, 1871: 93.

9 “Base Ball,” Boston Journal, September 13, 1871: 1.

10 “White Over Red,” Chicago Inter Ocean, September 30, 1871: 4.

11 Howard W. Rosenberg, Cap Anson 2: The Theatrical and Kingly Mike Kelly (Tile Books, 2004), 265, 266.

12 Buffalo Express of July 29, 1888, cited in Rosenberg, 266.

13 “The Sporting World,” Chicago Tribune, January 21, 1872: 2.

14 “Base Ball,” Boston Journal, May 8, 1872: 4.

15 Timothy Munn and Matthew F. Vitticore, From Backyards to Big Leagues: Ontario County Baseball 1850-2004 (Canandaigua, New York: Ontario County Historical Society, 2005), 59.

16 Newspaper advertisement dated June 20, 1872, in unknown newspaper, clipping found in Jackson’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

17 Email from Tim Munn to Priscilla Astifan, June 3, 2016.

Full Name

Samuel Jackson

Born

March 24, 1849 at Ripon, North Yorkshire (United Kingdom)

Died

August 4, 1930 at Clifton Springs, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.