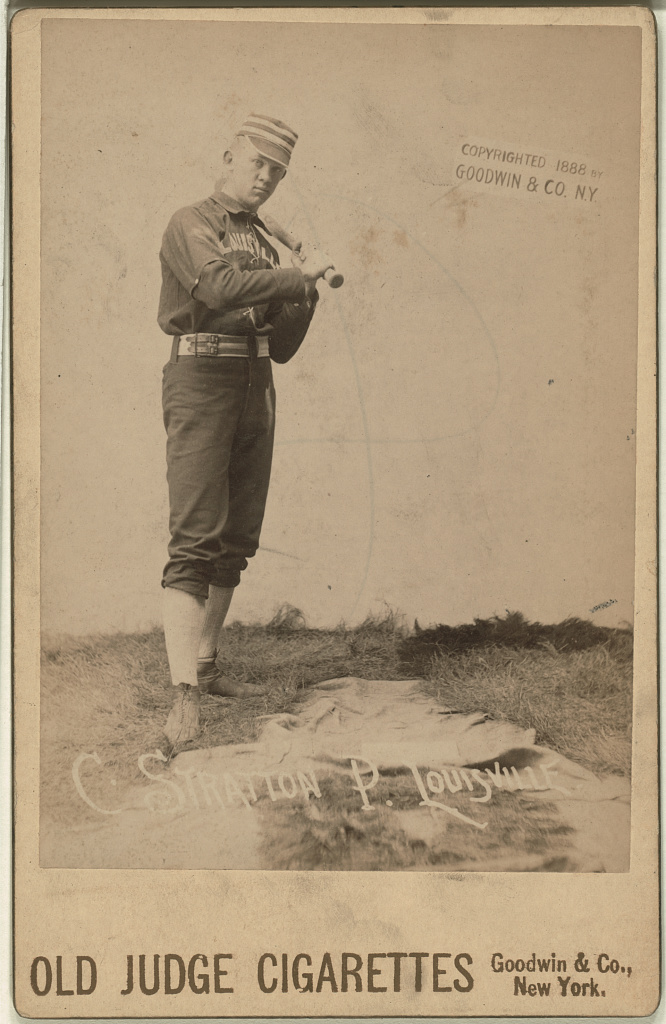

Scott Stratton

As a combination pitcher and outfielder in the nineteenth century, Scott Stratton appeared in 391 major-league games, 231 as a pitcher and another 160 games as an outfielder or first baseman. He is best remembered today for his religious scruples that limited his time on the baseball diamond during his eight-year career between 1888 and 1895.

Stratton was a Sabbatarian, i.e., a person who strictly observes Sunday as a day of rest, which caused him to refuse to play in Sunday ballgames. He was one of a dozen or so Sabbatarians in the history of major-league baseball.1 Following his rookie year in 1888, Stratton never played in a Sunday game, an obstacle he needed to overcome to survive another seven years as a Sabbatarian ballplayer into the 1895 season.

Chilton Scott Stratton was born on October 2, 1869, in Campbellsburg, Kentucky, the son of William H. and Anna Letitia (Scott) Stratton.2 Named after his maternal grandfather, (Chilton Scott), he usually went by his middle name, Scott, or the abbreviated C. Scott, rarely by Chilton. He was the oldest of his parents’ three children.3 Scott grew up as a young boy in Campbellsburg, a few miles east of Louisville, where his father settled after his discharge from the Union Army at the end of the Civil War.4 In the early 1880s the Stratton family relocated to Taylorsville, 30 miles south of Louisville, where his father, a druggist by trade, operated a mercantile store and post office.5

Stratton was “one of the best educated players in the profession,” according to his only known contemporary biography (published in 1896), which provided no detail about his schooling.6 He was surely educated in a private academy, given the poor state of public education in Kentucky at the time. Stratton likely attended the Spencer Institute, located in Taylorsville, which in the 1880s was “the principal provider of high school education in the community and the county” before a public high school opened in 1907.7 Spencer Institute was run by George Overstreet, a Presbyterian minister, and his wife.8

After playing several years for amateur baseball teams, Stratton had a tryout with the Louisville club in the American Association. Field manager John Kelly gave the 18-year-old Stratton a tryout in March of 1888. In an article headlined “Manager Kelly Pleased; He Thinks Young Stratton a Good One,” the Louisville Courier-Journal described the 6-foot, 180-pound right-hander as able to throw “all the curves, possesses speed and good control of the ball, and lacks only experience and self-possession.”9 After he signed Stratton to a contract, Kelly remarked that Stratton was “the greatest find of his base ball experience.”10

Kelly, though, was fired two months later, which began a carousel of manager changes for the team. As Louisville limped to a seventh-place finish, Stratton compiled a 10-17 record as pitcher and a .257 batting average as a left-handed hitter in 67 games (33 as pitcher and the others as an outfielder). Stratton pitched Louisville’s first Sunday home game that season, on April 29, as 7,000 people packed Eclipse Park to see the wunderkind from Taylorsville.

Louisville had a long history of hosting baseball games on Sunday, given the city’s large German-American population that preferred amusement rather than solitude on their only day off in the then six-day workweek.11 Sunday games were tolerated in Louisville despite the Kentucky law that stipulated that no work or business be conducted on Sunday except for works of necessity or charity.12 In 1882 Louisville hosted the first official major-league game played on Sunday and by 1888 was one of five Sunday-hosting cities in the American Association.13

Although he complained about playing on Sunday during the 1888 season, Stratton started nine Sunday games in the pitcher’s box and played the outfield in several others. It was not until contract negotiations for the 1889 season that Stratton expressed a rigid resistance to playing on Sunday. In an article headlined “Stratton Will Not Sign with Louisville If Compelled to Play Sunday Games,” the Louisville Courier-Journal explained that “Stratton has always been a devout member of the church, and has a Sunday-school class at Taylorsville” and that “his parents were bitterly opposed to it [Sunday playing].”14 The newspaper went on to report that “both Stratton and his parents say that rather than that he should play ball on Sunday, they much prefer to see him give up ball playing altogether.”

While the Courier-Journal didn’t specify the religion practiced by the Stratton family, their faith was surely Presbyterian, given his schooling at Spencer Institute and future facts. Presbyterians, among the many religions, held one of the most ardent Sabbatarian attitudes.15 Stratton’s Sabbatarian conviction was likely enhanced by his courting of Bessie Anderson, the daughter of wealthy George Anderson, who operated a 300-acre farm in Taylorsville.16

By late March of 1889, Stratton came to a salary agreement with Mordecai Davidson, the president of the Louisville club, conditioned on his not playing on Sunday.17 Newspapers reported that “Scott Stratton, the Louisville pitcher, will not play Sunday, and has a special stipulation in his contract letting him out on that day.”18

Stratton did not play on Sunday in 1889 and continued to have a strict Sabbatarian stance for the remainder of his baseball career. Stratton was able to make a living as a Sabbatarian ballplayer because the Louisville ballclub experienced constant change in its executive management, with a new club president each season from 1888 through 1893, as well as frequent turnover at field manager during Stratton’s first two years with the team.

As Louisville lost 111 games and stumbled to a last-place finish in the 1889 season, Stratton compiled a 3-13 record as pitcher during the first half of the season before leaving the team in mid-June. He returned in August as an outfielder and first baseman, producing a .288 batting average. Interestingly, Stratton arranged for Bill Anderson, the brother of the woman he wanted to marry, to pitch one game for Louisville that August.19

On January 26, 1890, Stratton married Bessie Anderson in a ceremony performed by Presbyterian minister J.M. Hutchinson in Jeffersonville, Indiana, just across the Ohio River from downtown Louisville.20 In an article headlined “Stratton’s Winning Run: The Young Base Ball Pitcher Elopes With Miss Bessie Anderson,” the Courier-Journal recounted in detail how Stratton and his bride-to-be eloped from Taylorsville and drove all night by horse-and-buggy on muddy roads to marry in Indiana. Rather than a ceremony in Taylorsville, the couple needed to elope due to “a serious obstacle in the parent of the young lady, who objected to the marriage, owing to her tender age.”21

Wire-service accounts of the clandestine marriage were published in newspapers across the country.22 Most focused simply on the elopement. A few newspapers carried the more salacious detail about how “her father objected to Stratton’s suit” (not his clothing, but rather the past tense of the verb “sue” that means to woo or propose marriage).23 Her father’s dislike for Stratton was likely less about Bessie being 20 years old and more due to his profession as a ballplayer, with its modest prospects for supporting his daughter in the fashion she was used to in the upper-income Anderson house. During the 1890 baseball season, since “Bessie’s father did not like Stratton and denied him the house,” the “baseballist” and his wife lived in Louisville rather than return to Taylorsville.24

Matrimony seemed to agree with Stratton, since he had the best season of his baseball career in 1890, leading Louisville from worst to first to become champion of the American Association. Stratton had a 34-14 record as pitcher, leading the league in winning percentage (.708) and earned-run average (2.36), despite not playing in his team’s 20 Sunday dates that season. His statistics, though, were inflated due to the diluted talent in the American Association that year when the newly launched Players’ League poached many of its best players.

By the fall of 1890, Stratton and his wife had returned to live in Taylorsville, as the family quarrel that had sparked their elopement was now patched up. Stratton opened a grocery store, which became his offseason job for several years. “Groceryman Scott Stratton had come to Louisville to lay in a supply of baked beans and canned corn for spring trade,” the Louisville correspondent to The Sporting News reported. “After adding to his supply of bees wax, calico and molasses, Scott took the evening train.”25

The twin effects of his sensational 1890 season and his impending family (Bessie was pregnant with their first child) caused Stratton to jump his Louisville contract before the 1891 season. He signed to play with Pittsburgh of the National League, since the money was irresistible ($4,500 salary) and Pittsburgh did not play Sunday games, which were prohibited in the National League.26 However, soon after signing with Pittsburgh, Stratton was reportedly bedridden with typhoid fever, so he did not join the team until mid-May. After he pitched just two games (and losing both), Pittsburgh released him. He rejoined Louisville for the remainder of the 1891 season, producing a 6-13 mark as pitcher.

In the summer of 1891 Bessie gave birth to a son, Fred Bodine Stratton.27 The baby boy was named after Bessie’s half-brother, Fred Bodine Smith, from her mother’s first marriage.

In 1892 the American Association merged with the National League, with the latter taking in four Association teams (including Louisville) to make a 12-team league. Sunday baseball was now permitted in the National League, which put added pressure on the Sabbatarian Stratton.

Being a father and the partial rest of his pitching arm in 1891 gave Stratton renewed vigor in the 1892 season, his only other decent season as a pitcher. He posted a 21-19 record with a 2.92 earned-run average, helped by pitching to hitters on NL teams who were unfamiliar with his delivery. It was the last year of the three-year period that Jack Chapman managed the Louisville team, which coincided with the period during which Stratton flourished as a pitcher.

In December of 1892, Stratton’s son Fred died in a fire when Bessie was six months pregnant with their second child.28 On March 15, 1893, she gave birth to a daughter, Mary Scott Stratton, who was their only child to survive to maturity.29

Before the start of the 1893 season, the new Louisville manager, Billy Barnie, traded Stratton to Chicago.30 However, the trade fell apart and Stratton returned to play for Louisville that year. He compiled a decidedly subpar 12-23 record with a 5.43 earned-run average, with 100 walks and just 43 strikeouts. Like many pitchers that season, Stratton suffered from the adverse effects of the lengthening of the pitching distance from 55 feet to 60 feet 6 inches. Stratton was more valuable as a spare outfielder who played in 24 games at that position in 1893.

Barnie tolerated the non-Sunday-playing Stratton in 1893 because Louisville couldn’t play home games on Sunday that season. To replace Eclipse Park, which had burned down in 1892, a new ballpark, called League Park, was built for the 1893 season. However, the new ballpark was located just outside the Louisville city limit on land in the town of Parkland, which had an ordinance prohibiting Sunday baseball.31 The Louisville club owners asked the state legislature to annex the property under the ballpark to the city of Louisville. While this landtaking allowed a Sunday game in early July, the town of Parkland appealed the annexation and obtained an injunction to stop future Sunday games until the court issued a ruling, which forestalled Sunday baseball in Louisville for the remainder of the 1893 season. After the baseball season ended, the court ruled that the annexation was legal, enabling Sunday baseball to return to Louisville for the 1894 season.

In 1894 Stratton played sparingly for Louisville, as manager Barnie sought to trade him to another team, most notably Boston or Philadelphia, which did not play on Sunday either at home or on the road. Finally, in late June, Stratton was traded to Chicago for reserve outfielder Sam Dungan. Stratton played some outfield and did some pitching (a respectable 8-5 record) for Chicago during the second half of 1894, but earned his keep as a hitter with a robust .374 batting average.

However, Chicago was a poor match for the Sabbatarian Stratton, which played Sunday baseball both at home as well as on the road. After being seldom used during the first half of the 1895 season, splitting his time between the outfield and the pitching rubber, Stratton was released by Chicago in July, since his pitching was so ineffective. The last game he pitched in professional baseball was on July 2, 1895, when he yielded 11 runs in the first inning to the lowly St. Louis Browns.

During his eight-year career in the major leagues from 1888 through 1895, Stratton compiled a 97-114 record as a pitcher and produced a .274 batting average.

Although Stratton was a devout Sabbatarian, there were few newspaper reports about his stance on Sunday baseball. “Scott Stratton is a gentleman and a player who has conscientious scruples. He left Louisville because he didn’t care about playing on Sunday,” the Boston Globe reported in 1891.32 “He is one of the few players who have it stipulated in their contracts that they are not to play Sunday ball. Stratton made this proviso with Springfield,” the Scranton Tribune reported in 1897.33

Stratton caught on with the St. Paul team in the Western League, where he reinvented himself to be strictly an outfielder. He played for St. Paul the remainder of 1895 and the entire 1896 season, as the ballclub was willing to tolerate his religious convictions against Sunday baseball.

After the 1895 season, Stratton announced that he was retiring from baseball, “desiring to devote his attention to his grocery store at Taylorsville, Ky.”34 His father-in-law was also sick and died in March of 1896.35 This began an annual cat-and-mouse game, as he retired every fall and then unretired in the spring.36 While helping his salary negotiation with minor-league teams, it also gave him the offseason time to establish a foundation for his post-baseball life.

For the 1897 baseball season, after he played briefly with the Springfield, Massachusetts, team in the Eastern League, Stratton joined the Reading, Pennsylvania, team in the Atlantic League. This minor league was a natural fit for his Sabbatarian beliefs because Pennsylvania had a very restrictive Sunday law regarding sports and only the two New Jersey-based teams hosted Sunday games in the Atlantic League. Stratton also played in Reading for the 1898 and 1899 seasons, before shifting to the Wilkes-Barre team for the 1900 season. When the Atlantic League disbanded in mid-June, Stratton caught on with Hartford of the Eastern League, where the 30-year-old Stratton played his last pro ballgame in September 1900.

Stratton and his family lived in Taylorsville during the 1890s.37 After his mother-in-law died in March of 1901, Stratton bought a farm for his family home in Bloomfield, 10 miles south of Taylorsville.38 They lived there for the next 25 years.39 Tobacco, one of the main crops at the Bloomfield farm, made Stratton a prosperous resident.40

Life in Bloomfield revolved around their daughter. “Mrs. Stratton and her bewitching little daughter, little Miss Mary Scott Stratton, are social favorites,” the Kentucky Standard, a weekly newspaper published in nearly Bardstown, reported.41 There were numerous mentions of the Stratton family as they “motored to Louisville” or “visited relatives in Taylorsville” in the society news of the local Kentucky Standard as well as the regional Louisville Courier-Journal.42

Stratton’s ties to the Presbyterian faith were more overt when his daughter matured. She attended Caldwell College, also known then as the Kentucky College for Women, which was a Presbyterian school.43 When she married Earl Otis on November 2, 1918, in a small wedding at the Stratton house in Bloomfield, a Presbyterian minister performed the ceremony.44

During the 1920s Stratton and his wife made frequent trips to Louisville to see their daughter and son-in-law, but there were no grandchildren to visit, since Earl and Mary had no children.45 By 1930 Stratton and his wife left the Bloomfield farm to reside full-time in Louisville.46

Baseball was a just a tiny part of Stratton’s adult life. He attended a minor-league game in Louisville in 1925 as part of a reunion of former Louisville major leaguers to celebrate the upcoming 50th anniversary of the founding of the National League.47 In 1937 he received national recognition in The Sporting News for his 15-game winning streak as a pitcher for Louisville during its 1890 championship season.48

Scott Stratton died on March 8, 1939, in Louisville and is buried at Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville.49

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Notes

1 Charlie Bevis, Sunday Baseball: The Major Leagues’ Struggle to Play Baseball on the Lord’s Day, 1876-1934 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 145-147.

2 No birth record can be located for Stratton. This birth date is cited in his death certificate (see footnote 49).

3 Federal census record for 1880 for Chilton Scott (grandfather), Campbellsburg, Henry County, Kentucky.

4 W.H. Perrin, Kentucky: A History of the State, 6th edition (Louisville: F.A. Battey, 1887), 858.

5 Obituary of W.H. Stratton, Kentucky Standard (Bardstown, Kentucky), September 5, 1912.

6 Biography of C. Scott Stratton, New York Clipper, April 11, 1896.

7 Shelburne-Cox House application in 1992 to National Register of Historic Places, in National Park Service records.

8 Presbyterian Ministerial Directory (Cincinnati: Armstrong and Fillmore, 1898), 427.

9 Louisville Courier-Journal, March 28, 1888.

10 Chicago Inter Ocean, April 15, 1888.

11 Bevis, Sunday Baseball, 25.

12 Abram Herbert Lewis, A Critical History of Sunday Legislation from 321 to 1888 A.D. (New York: Appleton, 1888), 221-222.

13 Bevis, Sunday Baseball, 36.

14 Louisville Courier-Journal, February 24, 1889.

15 Alexis McCrossen, Holy Day, Holiday: The American Sunday (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 23, 49; Scott Miyakawa, Protestants and Pioneers: Individualism and Conformity on the American Frontier (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 124.

16 Bourne-Anderson House application in 1977 to National Register of Historic Places, in National Park Service records; Perrin, Kentucky: A History, 739. The Anderson farm was owned by the Anderson family from 1844 to 1933.

17 Louisville Courier-Journal, March 31, 1889.

18 Rocky Mountain News (Denver), April 30, 1889.

19 Anderson played under the assumed name of George Robinson at the time. It was his only major-league appearance.

20 Marriage records for 1890 in Clark County, Indiana (page 297). Hutchinson was the pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of Jeffersonville from 1871 to 1896.

21 Louisville Courier-Journal, January 27, 1890.

22 Buffalo Evening News, January 27, 1890; Washington Evening Star, January 27, 1890; Rome (New York) Daily Sentinel, January 28, 1890; Indianapolis Sun, January 29, 1890.

23 New York Sun, January 28, 1890.

24 Boston Globe, August 31, 1891; Louisville City Directory, 1890.

25 The Sporting News, March 14, 1891.

26 Pittsburgh Dispatch, March 1, 1891.

27 No birth record can be located for Fred Stratton. The birth timing is from an August 31, 1891, article in the Boston Globe and the date on the family headstone in Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville, Kentucky, at findagrave.com website.

28 Date of death is from family headstone in Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville and a December 30, 1892, article in the South Haven (Michigan) Messenger.

29 No birth record can be located for Mary Stratton. This birth date is from her burial record at the website of the Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

30 Chicago Inter Ocean, March 28, 1893.

31 Bevis, Sunday Baseball, 108-109.

32 Boston Globe, April 22, 1891.

33 Scranton Tribune, May 26, 1897.

34 St. Paul Globe, January 7, 1896

35 Records of Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville; obituary of George Anderson, Louisville Courier-Journal, March 31, 1896.

36 For example, see St. Paul Globe, December 11, 1896, and Wilmington (Delaware) Sun, October 6, 1898.

37 Federal census record for 1900 for Mary Anderson (mother-in-law), Taylorsville, Spencer County, Kentucky. Stratton was recorded that year living in a boarding house where he was playing baseball that spring: James Poland (hotel keeper), 74 East Market Street, Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

38 Records of Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville; obituary of Mary Anderson, Louisville Courier-Journal, March 22, 1901.

39 “Bloomfield,” Kentucky Standard, May 28, 1903; federal census record for 1910 for C. Scott Stratton, Bloomfield, Nelson County, Kentucky.

40 United States Tobacco Journal, April 5, 1911; Kentucky Standard, January 27, 1916, and February 3, 1921.

41 Kentucky Standard, November 19, 1903.

42 Kentucky Standard, November 8, 1910, and May 23, 1912; Louisville Courier-Journal, March 2, 1907, and July 4, 1914.

43 Kentucky Standard, September 15, 1910, and April 4, 1912.

44 “Stratton-Otis Wedding,” Kentucky Standard, November 7, 1918.

45 Obituaries of Mary Stratton Otis and Earl Otis, Louisville Courier-Journal, July 14, 1971, and December 23, 1966. They are both buried at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

46 Federal census record for 1930 for C. Scott Stratton, 1244 Fourth Street, Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky; Louisville City Directory, 1933.

47 Louisville Courier-Journal, September 23, 1925.

48 The Sporting News, November 25, 1937.

49 Death records for 1939 in the Commonwealth of Kentucky (certificate number 7137); records of Valley Cemetery in Taylorsville.

Full Name

Chilton Scott Stratton

Born

October 2, 1869 at Campbellsburg, KY (USA)

Died

March 8, 1939 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.