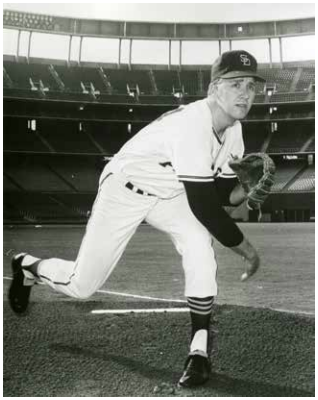

Steve Arlin

Right-handed pitcher Steve Arlin always knew there was more than baseball. After leading the Ohio State University to two consecutive berths in the College World Series and a national title in 1966, he brokered an unusual professional baseball contract that permitted him to pursue a degree in dentistry in the spring and early summer. Dr. Arlin eventually became the sport’s most famous dentist during his six-year career in the majors (1969-1974), spent mostly with the moribund, cellar-dwelling San Diego Padres, whose ineptitude as an expansion team was surpassed by only the New York Mets. Arlin also has the dubious distinction of leading the NL in losses in consecutive seasons. “It was more than a little frustrating,” said Arlin of playing for such terrible teams, and he recalled how sportswriters often joked that he “ought to sue the team for malpractice.”1

Right-handed pitcher Steve Arlin always knew there was more than baseball. After leading the Ohio State University to two consecutive berths in the College World Series and a national title in 1966, he brokered an unusual professional baseball contract that permitted him to pursue a degree in dentistry in the spring and early summer. Dr. Arlin eventually became the sport’s most famous dentist during his six-year career in the majors (1969-1974), spent mostly with the moribund, cellar-dwelling San Diego Padres, whose ineptitude as an expansion team was surpassed by only the New York Mets. Arlin also has the dubious distinction of leading the NL in losses in consecutive seasons. “It was more than a little frustrating,” said Arlin of playing for such terrible teams, and he recalled how sportswriters often joked that he “ought to sue the team for malpractice.”1

Stephen Ralph Arlin was born on September 25, 1946, in Seattle, Washington, to Ralph Wampler and Darlene (Mahns) Arlin. His grandfather, Harold Wampler Arlin, was the world’s first salaried baseball broadcaster, for KDKA in Pittsburgh, where he made history by announcing the game on August 5, 1921, between the Philadelphia Phillies and Pirates at Forbes Field, as well as the first football game about two months later. By the time Steve started elementary school, the Arlins had relocated from the Pacific Northwest to Lima, Ohio, located about 170 miles west of Cleveland, where his father worked as an electrical engineer. Steve starred on the hardwood and diamond at Shawnee High School in Lima, and also played American Legion ball in the summers.

Arlin attended Ohio State on a baseball scholarship and became one of the most dominant pitchers in college baseball history. A two-time All-American, Arlin led the Buckeyes to the College World Series as a sophomore in 1965 (freshmen were not eligible for varsity athletics at the time). He emerged as the hurling star of the double-elimination tournament, setting a series record by fanning 20 in a complete-game 15-inning, 1-0 shutout of Washington State.2 The Buckeyes ultimately lost to the Sal Bando– and Rick Monday-led Arizona State Sun Devils in the championship; however, Arlin was named to the all-tournament team. He paced the NCAA with 165 strikeouts (including 31 in the CWS) in 141 innings and victories (13), tied with ASU’s Jim Merrick, and was named the National College Pitcher of the Year.3 Despite Arlin’s well-publicized intentions to return to OSU for his junior year, the Detroit Tigers hoped to change his mind by offering him a reported $80,000 bonus after selecting him in the 23rd round of the inaugural amateur draft in June. Arlin did not take the bait and was back in Columbus in the fall. Described as the “greatest one-man show ever seen in the College World Series,” Arlin led the Buckeyes to their first (and as of 2016) only CWS baseball title, in 1966.4 He pitched in five of his team’s six games, twice defeated the number-one-ranked University of Southern California, finished the tournament with 28 strikeouts in 20⅔ innings while yielding just two runs and five hits, and was named the tournament’s most outstanding player. In his two-year varsity career, he set Buckeye records for victories (24-3) and strikeouts (294), both since broken. He was subsequently inducted to the OSU Athletic Hall of Fame (1976), the College Baseball Hall of Fame (2008), and the Omaha College World Series Hall of Fame (2014).5 In 2004 Arlin became the first baseball player in OSU history to have his number (22) retired.

Arlin was primed for the next stage of his career, which began when the Philadelphia Phillies selected him with the 13th pick of the first round of the amateur draft (secondary phase) in June. Enticed by a reported $105,000 bonus, believed to be the Phillies’ largest-ever at the time, Arlin signed on June 22, 1966, at a ceremony at his parents’ house in Lima.6 Scout Tony Lucadello, who had followed Arlin since his prep days, was credited with the signing. Arlin picked up an additional bonus that December when he married Susan Lynn Bazler from Upper Arlington, outside Columbus, Ohio. Together they had two sons.

Arlin’s three-year stint in the Phillies’ farm system was anything but smooth. After raising eyebrows with the Bakersfield Bears in the Class-A California League (116 strikeouts in 110 innings) in 1966, he earned a look-see at the Phillies spring training in 1967, but by the end of March the young hurler was back in Columbus enrolled in dental school at OSU. Consequently, he missed most of spring training and reported to Reading in the Double-A Eastern League in mid-June. This arrangement ruffled feathers in the Phillies organization, especially among coaches who questioned the hurler’s commitment to baseball. Among Arlin’s few highlights was a seven-inning no-hitter for Reading, but that came with the caveat of 10 walks.

Arlin possessed a heater in the low 90s and a knee-buckling curve, but struggled with control, and failed to live up to the Phillies expectations. His obligation to dental school limited him to a dismal 5-15 record and just 161 innings with 100 walks in 1967-1968, while he worked his way up to Triple-A San Diego (Pacific Coast League).

While Phillies brass blamed the time Arlin missed in spring training and the early season for his failure to develop into a bona-fide starter, Arlin had a different perspective. “Philadelphia mishandled me in the minor leagues,” he told sportswriter Bill Ballew.7 Arlin explained how pitching coaches, especially Al Widmar, changed his pitching mechanics so that he could throw even harder, but the results were catastrophic. “They turned my whole motion around,” he said. “They made me turn my butt toward the plate more. When I finished the motion, I’d fall off to first base instead of always finishing in good defensive position. So I actually did everything in the major leagues without the good curveball.”8

The book closed on Arlin in Philadelphia on October 14, 1968, when the San Diego Padres selected him with the 57th pick in the expansion draft. “There’s no telling how good Arlin might be if he gets a full spring training behind him,” said Padres GM Eddie Leishman.9 Like the Phillies, the Padres would have to wait to find out. Skipper Preston Gomez seemed to lose interest in the 23-year-old hurler when he chose dental school over spring training. When Arlin finally reported to the big-league club in mid-June of 1969 for his first competitive baseball of the season, Gomez was unimpressed. “[Arlin] doesn’t look like a ball player,” Gomez said of the sandy-haired youngster with glasses. “I thought he was some kid Eddie (Leishman) had sent down to pitch batting practice.”10 Arlin’s debut on June 17 in the second game of a doubleheader against the Los Angeles Dodgers probably didn’t change Gomez’s mind. Arlin yielded an RBI single, a wild pitch, a walk, and a three-run homer to the first three batters he faced. Two weeks later Arlin (11 earned runs and nine walks in 10⅔ innings) was back in Columbus, but this time it was a demotion to the Jets, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ affiliate in the Triple-A International League (the Padres launched a Triple-A team the next season). Arlin’s 2-5 slate with 4.73 ERA did not warrant a September call-up.

Graduating from dental school in June 1970, Dr. Arlin reported to the Salt Lake City Bees in the PCL. Predictably, he struggled as he worked himself into shape, posting a 5-7 record with a dismal 6.10 ERA in 87 innings. With the Padres en route to their second straight last-place finish in the NL West, Arlin was recalled on September 4. Bombed in his first outing (11 baserunners and four runs in a 3⅔-inning no-decision), Arlin shocked the Padres with a masterful seven-hit shutout with just one walk against the Atlanta Braves on September 23 for his first big-league victory. “He has a major-league arm,” cooed pitching coach Roger Craig. “There’s no reason why he can’t be a big winner.”11

In late February of 1971 Arlin reported to Yuma, Arizona, to participate in his first complete spring training as a professional. He admitted that missing spring training every season affected his development. “I’d come in pretty far behind everybody,” he said. “I never really did get into shape.”12 However, Arlin had no apologies for his decision to attend dental school. “I never thought about doing it differently,” he told sportswriter Ron Rapoport, “All the people want is production. I understand that. I wanted school behind me.”13

Widely expected to join the starting rotation, the 25-year-old Arlin impressed Gomez with his poise, demeanor, and approach to the game. “He’s the kind of pitcher who learns from his mistakes,” said the Cuban-born skipper. “He hasn’t pitched that much in pro ball, but he has the maturity that some of our others pitchers lack.”14 Hurling for the major leagues’ worst offense (3.02 runs per game) and the NL’s second most porous defense proved more challenging than expected for the cerebral Arlin. He lost 11 of his first 13 decisions. (Both victories were shutouts.) Then he suddenly hit a groove over a 14-start stretch from June 30 to September 3, going 7-5 and posting a 2.43 ERA in 107⅓ innings.

Arlin’s future looked bright, and never did it shine brighter than on July 25 in the second game of a doubleheader against the future World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates at San Diego Stadium. Nursing a 2-0 lead with two outs in the ninth and a runner on, Arlin induced the eventual major-league home-run leader, Willie Stargell to foul off seven successive pitches on a 3-and-2 count before walking him. Unfazed, he ended the game by whiffing the next batter, pinch-hitter Roberto Clemente, to complete a three-hit shutout. The Padres finished with the NL’s worst record (61-100) for the third straight season, but their young pitching staff emerged with the NL’s third-best team ERA (3.22), which produced a “note of optimism about the future,” suggested Padres beat writer Paul Cour.15 While 23-year-old Clay Kirby (15-13, 2.83 ERA, 231 strikeouts) and Dave Roberts (14-17, 2.10 ERA) garnered most of the attention Arlin posted nine wins (all by complete game), a team-best four shutouts, and a respectable 3.48 ERA in 227⅔ innings. He was also a tough-luck loser, leading the NL with 19 defeats; in 13 of those the Padres scored two runs or less; in four more, they scored three runs.

Eleven games into the 1972 season, Preston Gomez was fired for what beat writer Phil Collier described as the “defeatist complex” permeating the clubhouse.16 Into the void stepped Padres coach and first-time skipper Don Zimmer, who vowed to make his club better prepared mentally. If anything, the Padres took a step back. The Padres were once again the lowest-scoring team in the NL (3.19 runs per game), while their promising pitching corps finished with the second-worst team ERA in the league. That toxic mix produced another last-place finish in the NL West. Arlin gave Zimmer his first of 885 wins as a manager by outdueling red-hot Steve Carlton on April 29 in San Diego. He tossed a stellar five-hitter to beat the Phillies, 4-0, and exact a measure of revenge against the organization that gave up on him. He spun another shutout (a four-hitter against the New York Mets’ Jerry Koosman at Shea Stadium) in his next start, part of a career-long 19⅓-scoreless-inning streak. Sports pages had a field day with Arlin’s dentist title. “Dr. Arlin Pastes Pirates in the Teeth,” and “Padres Pitching Dentist Numbs Bucs,” following his masterful two-hit blanking of the Pirates on June 18, were typical of the kinds of headlines about the hurler’s accomplishments.17 That victory inaugurated an eight-start stretch during which Arlin did his best Nolan Ryan impression. He yielded just 33 safeties in 71 innings, tossed three two-hitters and a one-hitter, and surrendered just one hit in a career-long 10-inning outing in an eventual 14-inning Padres victory over the Mets. Bad luck sometimes followed Arlin even when he won a game. One strike from a no-hitter against the Phillies on July 18, Arlin yielded what sportswriter Bruce Keidan of the Philadelphia Inquirer described as a “bad hop” single to Danny Doyle.18 “I beeped it up for him,” said Zimmer, who had mysteriously ordered third baseman Dave Roberts to play shallow to guard against a bunt.19 Noticeably aggravated and shocked, Arlin balked facing the next batter, Tom Hutton, whose subsequent RBI single ruined the shutout, though Arlin still won the game. Sporting an impressive 2.80 ERA despite an 8-11 record, Arlin was widely expected to be named to the NL All-Star squad, but was snubbed. “I can’t believe there are nine pitchers in the league better than Steve,” said Roger Craig incredulously.20 After the All-Star break, Arlin was plagued by the same shoulder pain that bothered him the previous season. At one point he had lost 14 of 15 decisions, including 10 in a row, and ultimately finished the season with 10 wins and a major-league-most 21 defeats (as well as an NL-most 122 walks and 15 wild pitches). He lost seven one-run games; in 19 of the losses, the Padres scored three runs or less (31 total runs).

Given his 20-41 career record after the ’72 campaign, it’s no surprise that the competitive Arlin expressed his frustration publicly. “[I find this] very difficult to live with,” he replied when asked about losing 21 games. “I felt at the time of the All-Star break, I was one of the better pitchers in baseball.”21 Arlin’s career highs in innings (250), starts (37), complete games (12), and strikeouts (159) could not soothe his disappointment. “I’m in a profession in which the object is to win, and all I do is lose.”22

Arlin might have wished that offseason rumors about his trade to the Boston Red Sox in a multiplayer transaction involving Red Sox Reggie Smith and Rico Petrocelli had proved to be true. When the Padres got off to a horrible start in 1973, players were “close to rebellion” against skipper Zimmer, the coaching staff, and the front office.23 Arlin, pounded in his first five starts (5.40 ERA), was shunted to the bullpen for six weeks, during which time he and his teammates were jolted by a statement from the Padres’ majority owner, entrepreneur-banker C. Arnholt Smith. With his bank on the verge of failure,24 Smith agreed to sell the club to a consortium led by Joseph Danzansky, a Washington, DC, grocery-store magnate who intended to relocate the club to the nation’s capital. “All of us were in a state of shock,” said Arlin, “and depressed the rest of the season.”25 With the staff in shambles, ultimately finishing 11th in the NL in team ERA (4.16), Arlin rejoined the rotation and enjoyed some unexpected success. After tossing a three-hit shutout against the Houston Astros in the Astrodome on June 30, Arlin blanked the Dodgers on two hits five days later in Los Angeles to complete a surprising sweep on the division leaders. While Zimmer further alienated his player by calling the sweep a “1000-to-1 shot,” Arlin took aim at everyone but the players in a postgame tirade.26 “I want to make a splash for this team,” he said. “We play in a town where no one recognizes us. You never see our pictures hanging in a bar. … All that’s written about is the move to Washington.”27 Arlin tossed his third shutout in four starts, beating the Chicago Cubs, 1-0, at Wrigley Field on July 17, but struggled thereafter for the lowest-scoring and worst defensive team in the majors. Despite his finishing with a team-high 11 victories (and 14 losses), Arlin’s 5.10 ERA (in 180 innings) was the highest among qualified starters in the NL as the Padres lost 102 games and once again finished last in the West Division. Just days before the season concluded, Arlin cast doubts about his future. “I know my attitude has been brutal,” he admitted. “I don’t think I ever want to play another season like this. For the first time in my life, my favorite sport has not been fun for me.”28

On December 11, 1973, all 11 NL club owners approved Smith’s sale of the Padres to Danzansky. The club was slated to play its home opener on April 4, 1974, at RFK Stadium.29 Topps Baseball Card Co. even printed cards showing Padres players with “Washington Nat’l Lea.” as the team affiliation. But the dream of baseball in Washington was fleeting as legal battles soon halted the sale. Smith, under investigation for embezzlement and being sued for breaking the San Diego Stadium lease, changed course and sold the club to Ray Kroc, billionaire founder of McDonald’s, who promised to keep the team in San Diego.

The mood at the Padres’ spring training in Yuma was noticeably more optimistic in 1974. John McNamara had replaced Zimmer as pilot, and Bill Posedel, former pitching coach/guru of the Oakland A’s, was coaxed out of retirement. Kroc’s deep pockets also helped as the king of burgers signed aging slugger Willie McCovey and former All-Star second sacker Glen Beckett. Arlin, however, was not a happy camper. His personal nemesis, Buzzie Bavasi, was still the general manager, and their relationship was toxic. “He spent more time belittling his players than building them up,” said Arlin scornfully.30 Throughout the offseason, Arlin had demanded a trade, and then ridiculed Bavasi in the press for not honoring his wish. “I couldn’t take it anymore,” said Arlin about the losing.31 Compounding the problem was Arlin’s sore shoulder, ultimately diagnosed as a torn rotator cuff. “I should have been on the disabled list the rest of the season,” said Arlin after he retired.32 He finally got his wish on June 15, when the Padres sold him to the Cleveland Indians in a waiver transaction for two players to be named later. (Cleveland sent pitchers Brent Strom and Terry Ley six days later to complete the trade.) The Indians harbored few expectations for the beleaguered hurler, whose 1-7 record and 5.91 ERA had earned him a demotion to the Padres bullpen. Arlin made only 10 starts for the Tribe, notched just two victories, and posted a whopping 6.60 ERA in 43⅔ innings before his ailing rotator cuff made it impossible to throw.

“I felt like in 1975 I’d win 15 games,” said Arlin candidly years after his playing days were over.33 His shoulder felt fine after six months of rest in the offseason, but Arlin chose to retire instead. “I don’t need any more hassles,” he said when asked why he had not reported to the Indians’ spring-training facility in Sarasota.34 With a 34-67 career record, including 11 shutouts, and a 4.33 ERA in 788⅔ innings, Arlin quit baseball at the age of 29. (He batted .139 with 32 hits.) He enjoyed great success against Willie Stargell (.185, 5-for-27), Joe Torre (.167, 3-for-18) and Dave Concepcion (.095, 3-for-21); but was lit up by Bob Watson (.464, 13-for-28), Ralph Garr (.459, 17-for-37), and Garry Maddox (.423, 11-for-26).

Unlike many athletes, Arlin did not worry about transitioning to life away from sports. Baseball’s most famous dentist established a private practice in San Diego, where had practiced for more than 25 years and retired in 2004.

Arlin died on August 17, 2016, at the age of 70. He was survived by his wife, Robin, and his sons, Scott and Steve, from his first marriage.

“He had a great arm, great stuff,” remembered former Padres teammate and 1976 Cy Young Award winner Randy Jones. “Probably wasn’t the best command in the world, but on the days he had good command he was lights out. He just loved to compete. He did things the right way and he had an edge on him. It was a lot of fun to watch him compete and I learned a lot from him.”35

Last updated: September 23, 2020 (ghw)

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Arlin’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 Bill Ballew, “Steve Arlin: Ohio State Star May Have Been Best Ever in College Ranks,” Sports Collectors Digest, September 23, 1994: 141.

2 Associated Press, “Ohio State Whiz Hurls Big Shutout,” Tallahassee (Florida) Democrat, June 11, 1965: 12.

3 United Press International, “Sports Greats Trek to Columbus For TD Club Banquet,” Daily Times (New Philadelphia, Ohio), January 20, 1966: 14.

4 Bob Williams, “Buckeyes Bag Bunting as No. 1 College Team,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1966: 2.

5 See “Baseball: Steve Arlin Elected to Hall of Fame,” OhioStatebuckeyes.com, ohiostatebuckeyes.com/sports/m-basebl/spec-rel/030508aaa.html; National College Baseball Hall of Fame, collegebaseballhall.org/hall_of_famers.jsp?year=2008; and the Omaha College Baseball Hall of Fame, collegehomerunderby.com/omahahof.

6 Allen Lewis, “Arlin Given Reported $105,000 by Phillies,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1966: 15.

7 Ballew: 140.

8 Ibid.

9 Paul Cour, “Padres Join List of Big Bidders for Phils’ Allen,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1968: 44.

10 Paul Cour, “Dental Student Arlin Curing Padre Bullpen Pain,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1969: 18.

11 Paul Cour, “Dentist Arlin Could Fill Padres’ Mound Cavity,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1970: 48.

12 Ron Rapoport, “Getting Arlin on Ball Field Tougher Than Pulling Teeth,” Los Angeles Times, March 24, 1971: III, 3.

13 Ibid.

14 Paul Cour, “Dentist Arlin Wins Padres’ Mound Berth,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1971: 37.

15 Paul Cour, “Sharp Pitching Pierces Padres’ Gloom,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971: 11.

16 Phil Collier, “New Boss Cracks Downs on Bumbling Padres,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1972: 17.

17 Charley Feeny, ‘Dr. Arlin Pastes Pirates in the Teeth,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 19, 1972: 12; Bob Smizek, “Padres Pitching Dentist Numbs Bucs,” Pittsburgh Press, June 19, 1972: 24.

18 Bruce Keidan, “Doyle Ruins Arlin’s No-Hitter in 9th,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1972: 25.

19 Ibid.

20 Phil Collier, “Low-Hit Gems Are Arlin’s Specialty,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1971: 17.

21 Furman Bisher “A Dentist in the House?” The Sporting News, October 14, 1972:10.

22 Ibid.

23 Phil Collier, “Buzzie, Players, Discuss Mutiny Report,” The Sporting News, May 19, 1973: 13.

24 Smith was majority owner of United States National Bank in San Diego. When the bank collapsed in 1973, it was the largest bank failure in US history.

25 Phil Collier, “Padres Preach New Gospel With Kroc’s Blessing,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1974: 3.

26 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers’ Skid at Six, 3-0, on Arlin’s 2-Hitter,” Los Angeles Times, July 6, 1973: III, 1.

27 Ibid.

28 UPI, “Padres No Longer Located,” Times Standard (Eureka, Californian), October 1, 1973: 10.

29 Jake Russell, “San Diego Padres Were Once So Close to Moving to DC, They Had Uniforms Made,” Washington Post, June 16, 2016.30 Bob Nold, “Arlin Determined to Show Bavasi,” Akron (Ohio) Beacon-Journal, July 4, 1974: C5.

31 Ballew, 141.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Tom Callahan, “Trying Spring for Dr. Allen,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 9, 1975: 4C.

35 Jeff Sanders, “Former Padres RHP Steve Arlin Dies at 70,” San Diego Union-Tribune, August 22, 2016.

Full Name

Stephen Ralph Arlin

Born

September 25, 1945 at Seattle, WA (USA)

Died

August 17, 2016 at San Diego, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.