Sue Kidd

Born into a baseball family on September 2, 1933, during the first year of the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, Glenna Sue Kidd grew up playing ball and working with her close-knit family on the Kidd farm near Choctaw, Arkansas. She had three brothers – the youngest was Joe – and two older sisters, Juanita and Loretta. Sue, as folks called her, started as a toddler playing with a small rubber ball, and later she learned to throw the ball against the wall and catch it on the bounce. As a youth, she carried water to field hands, and sometimes she picked cotton and corn, the two main crops grown in the Mississippi River delta. Marvin Kidd sold his farm and bought a country store when he became the local postmaster in 1940, and he pursued his love of baseball by managing the town’s baseball team. Marvin’s team, including his two oldest sons, Marvin Jr., and Tommy, played teams from nearby towns, an American custom dating to the nineteenth century. As a teenager, Sue played a few times with her father’s nine, mostly pitching against a weaker team. A right-hander, she was the only local girl who had the talent, determination, and encouragement to play the national pastime, which was viewed as a man’s game in the 1940s.

Born into a baseball family on September 2, 1933, during the first year of the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, Glenna Sue Kidd grew up playing ball and working with her close-knit family on the Kidd farm near Choctaw, Arkansas. She had three brothers – the youngest was Joe – and two older sisters, Juanita and Loretta. Sue, as folks called her, started as a toddler playing with a small rubber ball, and later she learned to throw the ball against the wall and catch it on the bounce. As a youth, she carried water to field hands, and sometimes she picked cotton and corn, the two main crops grown in the Mississippi River delta. Marvin Kidd sold his farm and bought a country store when he became the local postmaster in 1940, and he pursued his love of baseball by managing the town’s baseball team. Marvin’s team, including his two oldest sons, Marvin Jr., and Tommy, played teams from nearby towns, an American custom dating to the nineteenth century. As a teenager, Sue played a few times with her father’s nine, mostly pitching against a weaker team. A right-hander, she was the only local girl who had the talent, determination, and encouragement to play the national pastime, which was viewed as a man’s game in the 1940s.

Further, baseball was the favorite sport in the nation’s rural regions when Sue was growing up. “That was about all there was for recreation,” Kidd recalled nearly sixty years later, “except for going to church. My brothers went to a baseball school in Greenbrier, Arkansas. That was run by Doc Williams. I believe his son was a major league scout. Dad wanted to send me to the baseball school, but of course they didn’t have facilities for a female.”

Sue continued to go to school, handle her chores, shag flies, and attend games of Choctaw’s team, but she had never heard of the All-American Girls Soft Ball League that Philip Wrigley and his associates launched in 1943. The Girls’ Pro League, as newspapers often called the increasingly popular league, expanded to eight teams in medium-sized Midwestern cities in 1946 while continuing to play a schedule of more than 100 games a season. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League started out playing modified fast-pitch softball with an underhand delivery, but with baseball rules like using nine players and allowing runners to lead off and steal bases. Continuing to evolve toward men’s baseball, the league shifted from sidearm to overhand hurling, baseball’s signature component, in 1948. By July 1949, the AAGPBL had decreased the ball in increments to a 10-inch circumference baseball (the ball used in 1943 was a 12-inch softball) while increasing the pitching distance to 50 feet and the base paths to 72 feet, distances that were made longer as the loop decreased the size of the ball, because the smaller baseball allowed batters to hit it harder and for more distance.

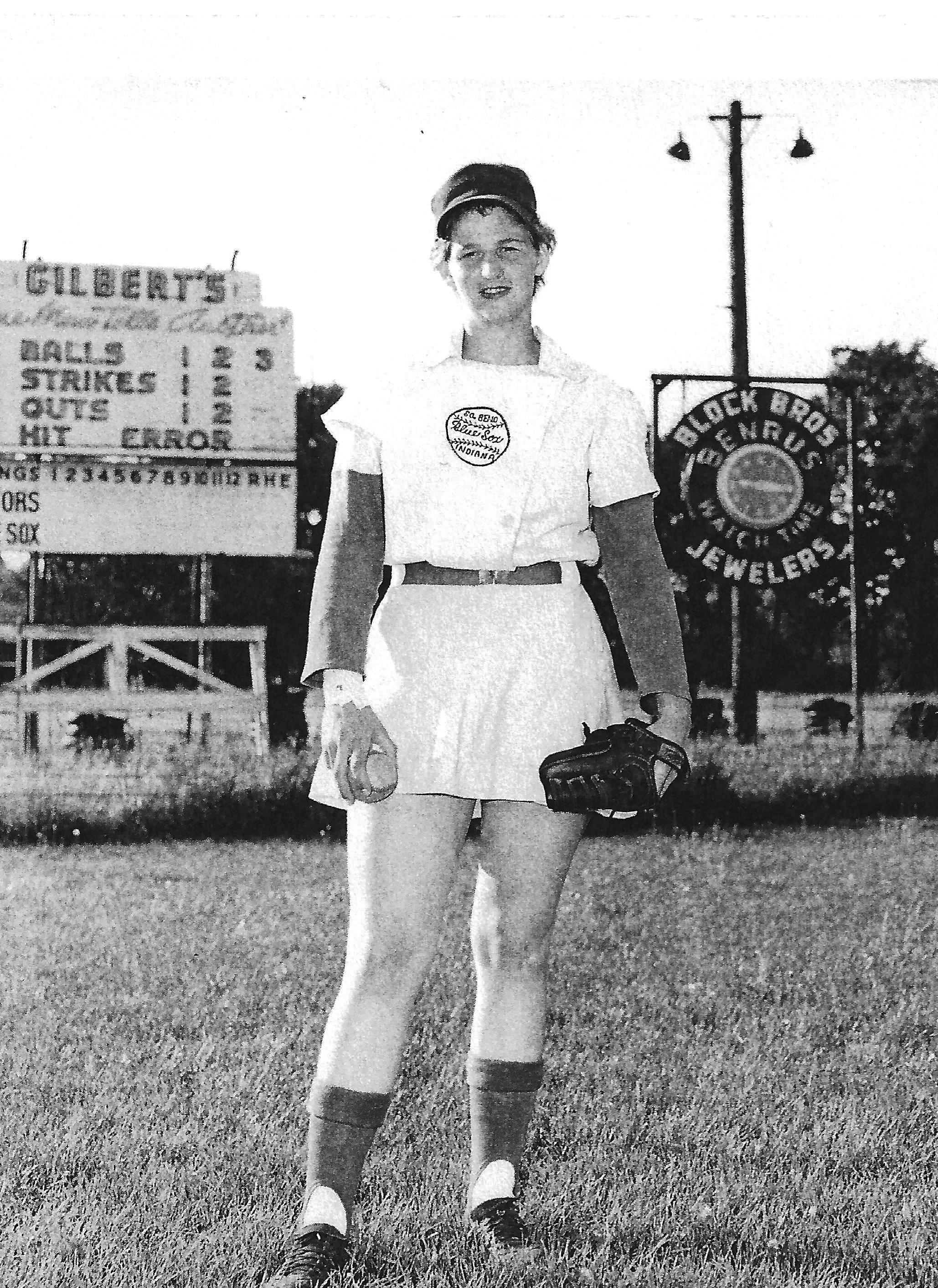

The women wore attractive, pastel-colored short-skirted uniforms, a fact that capitalized on their sex appeal. Reported league president Max Carey in the 1947 issue of Major League Baseball, “The players are typical American girls, school teachers, physical education teachers and students, high school and college students, clerks, models, librarians, secretaries, and office or factory workers in the off-season. They meet the highest standards of feminine appearance, deportment, and behavior and they are guided during their season by an individual team chaperone who acts as their counselor and friend.”

In early July 1949, the summer after Sue’s junior year at Clinton’s technical school, Marvin Kidd learned from Doc Williams that two AAGPBL touring teams, the Springfield Sallies and the Chicago Colleens, would play exhibition games in Little Rock. Marvin also saw the notice about two games in the local paper, and on the day of the first game, he drove his wife and 15-year-old daughter 75 miles to Little Rock. Sue tried out, the family watched the night’s contest, and they were told Sue made the league. They had to bring her back the next day with a packed suitcase to go on the road. After the drive home, the packing, and the return trip, the Kidds had to stop first at Little Rock’s Bureau of Vital Statistics to get their youngest daughter a birth certificate.

“I signed with the team, the Sallies,” Sue recollected, “and they put me in to pinch-hit in the game that night. After the game, we left on our bus, and the next stop was New Orleans. We traveled through about twenty-five different states that summer, and we ended up in West Virginia, I believe on Labor Day weekend. Dad sent my sister and her husband and my brother over to pick me up, so I wouldn’t have to try to get home on my own.

“During that year, I was fortunate enough to pitch a no-hitter, and what kept it from being a perfect game was an error by the shortstop. You know, that happens. I came back home and that year I finished my school at Clinton, over in the county seat. It was a vocational high school back then, but now it’s Clinton High School. I wasn’t eligible to play basketball, because I’d played professional baseball.”

Sue was thrilled to be able to play professional baseball in the summer of 1949, but she also learned a great deal from her teammates, notably Mary “Wimp” Baumgartner and Fran Janssen. A big, strong, hard-throwing right-hander who stood 5’8” and weighed 155, Sue took a lot of kidding about her Southern accent and country ways from the ballplayers on the tour. But the girls, like most ballplayers, laughed, joked, and enjoyed a heartfelt camaraderie. They were living their baseball dreams, and they welcomed the new rookie into their sorority. Wimp and Fran and others coached Sue on the proper skirts and blouses to buy, took her to have her hair cut professionally, and otherwise showed her the joys and difficulties of baseball on the road.

Lenny Zintak, the touring teams’ supervisor, was a huge help. The blue-eyed socially awkward blond teen from Choctaw remembered, “One day Lenny put his arm around me, and said, ‘Now, Sue, I want to give you some good advice.’ He said, ‘You just take this kidding and laugh it off, because that’s a sign that they like you. If they didn’t say anything to you, or were real derogatory, then that would mean they didn’t like you.’ I’ve always tried to remember that.

“I had my sixteenth birthday in early September, right toward the end of the tour, and I got on the bus that night. Lenny grabbed me and planted a big smackeroo on my mouth, kissed me big, and they began singing something like, ‘She’s Never Been Kissed,’ but I was able to laugh it off. I always tried to remember what Lenny said, ‘When they kid you, they like you.’ I took a lot of kidding living up north.”

After the tour ended, Sue traveled back to Arkansas, and at home she enjoyed a memorable baseball highlight: “On the twelfth of September, after I got back, Dad had a game set up in Heber Springs against a real good semipro team, the Heber Springs Merchants. I pitched that game over there, and I had good defense behind me and everything, and we won, 5-3. Dad tried to take me out in the seventh inning, but the fans wouldn’t hardly let him. He talked to me and said, ‘Well, we’ll go ahead and let you see if you can finish it.’ I was lucky enough to do that.”

The game Sue pitched became a local legend, and not a few of the Heber stars were embarrassed by the result. After all, this was 1949, and what macho ballplayer wanted to admit his team had been beaten by the pitching of a girl, or worse, that she struck him out? The fun started when Marvin Kidd was boasting to the manager of the tough Heber Spring Merchants, a local team, about his daughter’s prowess that summer as a pro pitcher. The exchange of remarks led to a challenge, and on Monday night, September 12, an overflow crowd of fans from Van Buren and Cleburne Counties, located in the foothills of the Ozarks, watched the two teams play at the new lighted ball field in Heber Springs.

When the cheering ended, although the buzz about the game lasted for many years, Sue had twirled a six-hitter, throwing mainly deceptive curve balls. She pitched out of several jams, thanks to good defensive plays by her teammates. Evidently no box score survived the exhibition, but Choctaw was leading 5-0 in the sixth frame, and the result was never in doubt. Sue’s mother wanted her to pitch only seven innings, but when a reliever warmed up in the bullpen during the seventh, the crowd chanted, “We want Sue!” Finally, Marvin relented, and his daughter worked the full nine innings. Several of the Heber players, interviewed in 1978 for a story about the game, denied letting up because Kidd was a teenager. Instead, the newspaper story reported how the men recalled the crowd “razzed them unmercifully during the game and for weeks afterward”!

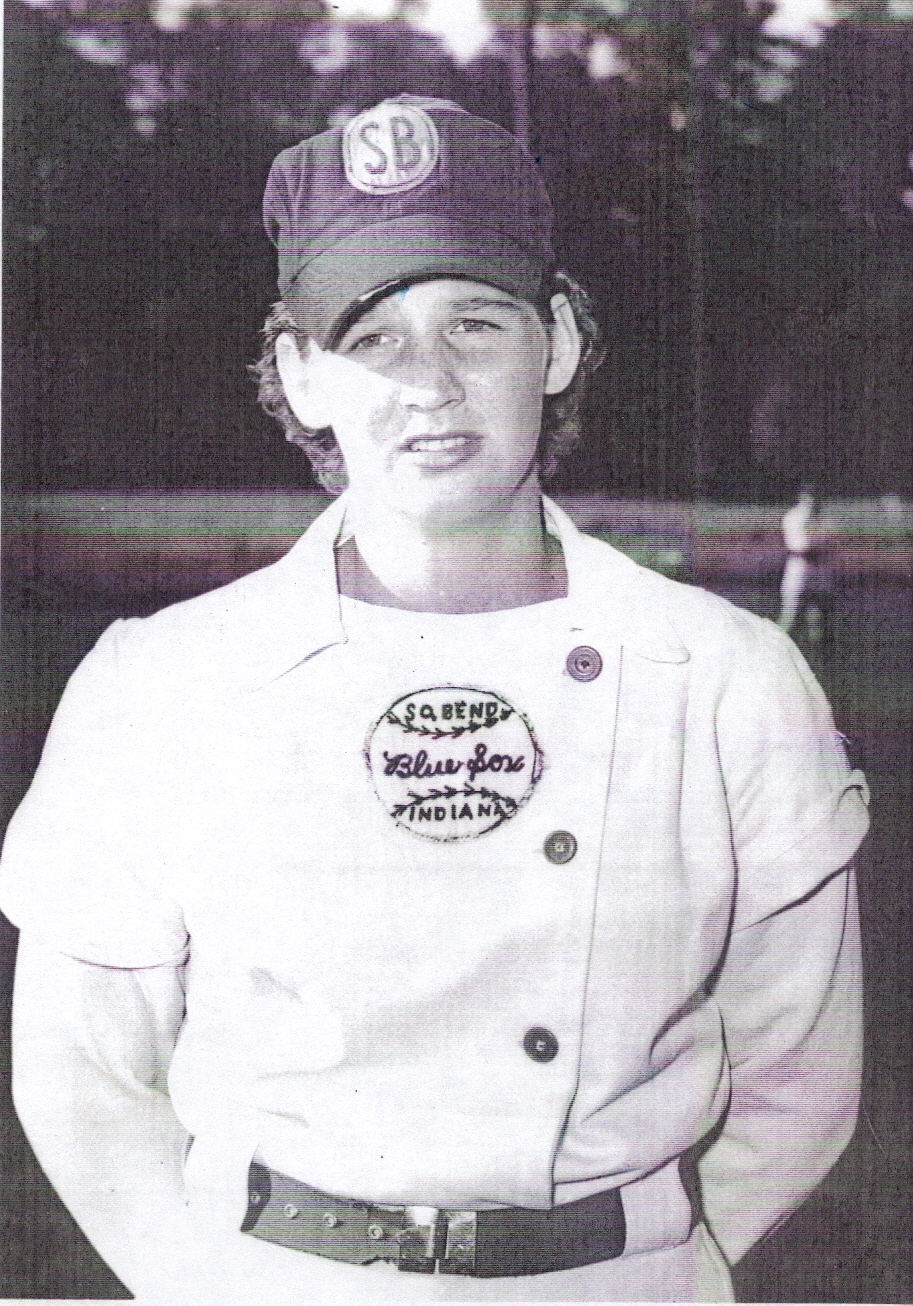

When she returned to spring training in 1950, Kidd was assigned to the Muskegon Lassies, one of the All-American League’s eight teams (the league peaked with ten teams in 1948). Midway through the season, she was traded to the South Bend Blue Sox, and, as it developed, she played for South Bend through 1954, the league’s final season. She well remembered those important years when she developed from a sixteen-year-old painfully shy recruit into a seasoned professional, but she always remained the talented, quiet, and respectful person of whom her father and mother were so proud.

“The next year, 1950,” Sue explained, “several of us rookies from that tour were assigned to the Muskegon Lassies. Lenny Zintak was the manager, and he’d been kind of the coach and manager on the tour. Mother and Dad took me to spring training at Cape Girardeau, Missouri, along with the Fort Wayne Daisies. Dad was pleased as punch, because he got to meet the big league star that was managing the Daisies, Jimmy Foxx. After about ten days, we headed north playing some exhibition games.

“When we got to Muskegon, we went to our rooms in private homes. We went to the ballpark, and it wasn’t a matter of a few days before they said there wouldn’t be a team in Muskegon that year. [Author’s note: Muskegon played until early June, when Kalamazoo bought the franchise.]

“I was sent to Peoria, Illinois, to the Redwings. I went there, but of course I didn’t know anybody there. I got along all right, and I pitched some good ball. I pitched a sixteen-inning game that we ended up losing about 2-1. It wasn’t too awful long after that when South Bend traded for me. I went to South Bend, the Blue Sox, and finished out 1950 with them.

“I had good stuff and everything, but I didn’t win a lot of games. One of the things, of course, I was a rookie, and they bunted on me, so I developed more skill on fielding bunts and stuff like that. I got pretty good at pitching, and I stayed on with South Bend for several years, through the 1954 season.”

Kidd was deeply competitive, and she relished the challenge of pitching well and winning each time she stepped on the diamond. In addition to hurling a moving fastball, Sue kept developing as a pitcher, improving her control, her variety of curves, and her “drop” ball, but the league changed for the 1951 season.

Kidd was deeply competitive, and she relished the challenge of pitching well and winning each time she stepped on the diamond. In addition to hurling a moving fastball, Sue kept developing as a pitcher, improving her control, her variety of curves, and her “drop” ball, but the league changed for the 1951 season.

The loop’s structure shifted to one of independent team owners instead of league ownership, a shift that accelerated a decline that set in after total attendance peaked in 1948 with 910,000 fans. Facing budget cuts based on declining admissions, the AAGPBL’s eight clubs voted in late 1950 to end the contract of the league’s Management Corporation. Arthur Meyerhoff, Wrigley’s chief advertising agent, operated Management skillfully from 1945 through the 1950 season. Meyerhoff supervised everything, including promoting the league nationally and regionally, hiring scouts, recruiting players, operating spring training camps, running the two rookie touring teams (where Kidd got her first opportunity) in 1949 and 1950, and handling the loop’s business. Forced to rely on each club managing everything from advertising to scouting new talent, the renamed American Girls Baseball League continued to slide toward insolvency.

Players, however, usually know, or care, little about a league’s business or a team’s finances, so long as they get their salaries and, the hope, raises for each season, and South Bend’s players were no exception. In 1951, The Blue Sox, now managed by former minor league hurler Karl Winsch, fielded a veteran team with a good pitching corps, led by the manager’s wife, Jean Faut. South Bend finished third in the first half of the league’s season (the season was divided in hopes of boosting attendance with a more exciting pennant race), but the Blue Sox led the league in the second half with a 38-14 ledger, fueled by a 16-game winning streak that started on August 11 and lifted the Indiana ball club into the Shaughnessy Playoffs.

The veteran Blue Sox team was improved by several good younger players in 1951, including Kidd. The youthful Blue Sox, who roomed and hung out together, included rookie right-hander Janet Rumsey, a tall, lanky curveballer; Gertie Dunn, a slick-fielding recruit shortstop; and Wimp Baumgartner, a second-year catcher who played alongside Kidd on the tour in 1949. Kidd and Rumsey became part of Winsch’s pitching rotation, but the stars were Jean Faut (15-7), later voted Player of the Year for 1951, and hard-throwing California sidearmer Lil Faralla (15-4), who began with the Blue Sox in 1948 but was loaned to Kalamazoo in 1950.

Kidd remembered, “We had a real good team in 1951, and a lot of good pitchers. During that season at one time, Battle Creek, Michigan, the Belles, had some injuries. They borrowed players off other teams, and I was ‘loaned’ to Battle Creek [on July 24, along with Gertie Dunn and Mary Dailey].

“Guy ‘Mudcat’ Bush was the manager there. He really gave me a lot of confidence, and in fact, he had me playing other positions besides pitcher. I stayed there about ten days to two weeks, and South Bend sent Jan Rumsey over and brought me back.”

South Bend won the Shaughnessy Championship for the first time in franchise history. The Blue Sox won the semifinal round of playoffs over the Fort Wayne Daisies in three games, and Faut pitched victories in the first and third contests. In the championship round, South Bend defeated the Rockford Peaches in the best-of-five series, with Faut hurling wins in games three and five and Jetty Vincent recording her team’s second victory in the fourth game. Kidd and Rumsey didn’t pitch in the playoffs, but they were thrilled to be part of the championship team.

In 1952, even as the league suffered further financial difficulties, South Bend fielded another experienced team with good players at every postion and a good pitching staff, now with Kidd and Rumsey serving as starters along with Jean Faut. The Blue Sox again had financial problems, and for a time it appeared that the owners would sell the team to Toledo, but in the end, Toledo’s backers vetoed the deal. Regardless, the on-field difficulties in South Bend resulted from the manager’s strict treatment of several players, notably second sacker Charlene “Shorty” Pryer. When she moved too slowly to suit the manger, who called on her to enter a game in the ninth inning on August 30, Karl Winsch suspended Pryer, and shortly thereafter, five other players, including veteran outfielder Lib Mahon, walked off the team in support of Pryer. That left South Bend with twelve active players, but one of those was Jean Faut, who posted a 20-2 record with an 0.93 ERA in the regular season and won three of four games she pitched in the playoffs, including the clinching 6-3 victory over Rockford to win the championship.

Kidd gave South Bend a big lift, finishing with a 13-7 record and a 2.00 ERA, but she and other younger players remained on the fringes of the controversy with the manager. Following a team meeting when outfielder “Jeep” Stoll and catcher Shirley Stovroff, two friends of Pryor, asked others to join the walkout, Sue called home. “At that age,” she recalled, “I wouldn’t do anything unless I checked with my folks. Dad said, ‘Certainly, do not leave. When it’s somebody else’s problem, you don’t know the full details.’

“I hated to see those good players quit, but it did give me more chances, and I also got to play other positions some. The last two years, I played more first base when not pitching. I guess between Wimp [Baumgartner], Jean [Faut], Betty Wagoner, Jetty Vincent, myself, to some extent, we were bound to win. Dad was a good aide also in telling us we could do the job.”

Kidd continued: “So I stayed on, and the Good Lord was with us, and we won that championship in 1952 with only twelve players. Jean Faut played her heart out, and so did the rest of us. She played third base when she wasn’t pitching, and I usually played right field, when I wasn’t pitching.

“In one of the games I was pitching, Rockford had a runner on third base and two out, and the next batter hit me like she owned me. Karl came out and called ‘Time out,’ and for one play he put me at third base and brought Jean in to pitch to get that batter out, and we went on to win that game.

“Talk about your knees knocking! I played third base when she pitched to that batter, and third base was one position I had never played. Karl wanted me to play in about halfway, and I could just imagine getting killed with a line drive, but I did it, and Jean got the batter for the last out.”

The league, however, was in dire financial straits, and the fact that only six teams were able to muster the funds to return for the 1952 season was one signpost along the road to bankruptcy. Players like Kidd recalled the signs of doom were obvious to everyone, notably the decreasing number of fans who attended games. By 1954, South Bend needed to average 1,000 fans per night to balance the books, but only twice did the Blue Sox draw more than that figure. In fact, after the Battle Creek franchise failed, five teams remained for the 1954 season: the Blue Sox, the Rockford Peaches, the Fort Wayne Daisies, the Kalamazoo Lassies, and the Grand Rapids Chicks. Resorting to the awkward device of three-team doubleheaders, the league juggled the schedule and managed to survive, but sometimes players drove cars to games instead of riding chartered buses, the major means of player transportation after World War II ended.

Kidd was pitching better than ever in 1953, as shown when the “iron-armed” star hurled and won both ends of a Fourth of July twin bill against visiting Grand Rapids at Playland Park. The Blue Sox captured the seven-inning opener (the standard format for AAGPBL twin bills) as Kidd twirled a four-hitter to win, 2-1. After twenty minutes of rest, the usual break between games, she returned and produced a seven-hit nine-inning performance (the format for second games of a twin bill), winning, 6-1, before an unusually large holiday crowd of almost 5,000 folks. Despite that crowd, South Bend’s attendance to date was 30 percent below the 1952 figures. But players keep playing ball, and for “Sue Kidd Night” four days later, on July 8, 1953, the Arkansas right-hander attempted to ride a mule onto the diamond – a joke about her country background. Instead, the balky beast would not cross the foul line, so Sue walked to the mound and proceeded to scatter seven hits to defeat visiting Kalamazoo, 6-2. She completed the season with a 13-15 ledger and a 2.37 ERA, but South Bend, minus the players who walked out in 1952, finished in fifth place, out of the playoffs.

Regarding the league’s impending demise, Kidd recollected, “We still rode the bus in 1953, and I think most of 1954. However, funds must have become hard to find toward the end of the ’54 season. I know cars were used some to travel to the closer games, Fort Wayne, Grand Rapids, and Kazoo perhaps. I don’t think we traveled by car to Rockford.

“I suppose, even though I didn’t want to believe the league would end, I guess I could see it coming. As I look back, I don’t remember Karl Winsch being too upset, or yelling too much, as I suppose he knew better than we that the league was coming to an end.”

The 1954 season proved anticlimactic, because the teams all suffered major losses, and none had hopes of playing in 1955. Still, the league worked on attracting more fans. By July, the circuit introduced a regulation baseball to replace the 10-inch ball used since mid-1949, lengthened the base paths from 75 feet to 85, and moved the mound back from 56 feet to 60. As expected, the regulation ball quickly boosted batting averages as well as the number of long balls hit, but it was too late for the circuit’s survival. South Bend, however, was strengthened by several trades and by the league’s player draft after the failure of the Battle Creek Belles. The Blue Sox acquired outfielders Wilma Briggs (.300, 25 HR, 73 RBI) and Betty Francis (.350, 8 HR, 58 RBI); outfielder-pitcher Helen Nordquist, who hit .310 and contributed two victories; slick infielders Mary Carey and Betty Wanless; and youthful right-hander “Dolly” Vanderlip, who won 11 games. Also, Betty Wagoner, the good-hitting, fleet Missouri outfielder playing her seventh season with South Bend, hit a career-best .320.

South Bend finished second in 1954 and reached the playoffs, but lost to Grand Rapids in the three-game semifinal round. The Blue Sox were led on the mound by Janet Rumsey, who posted a 15-6 mark with a 2.18 ERA, hurling her only no-hitter, and by Kidd, who produced a 9-6 mark (actually 9-5, according to a recount of games). Choctaw’s favorite daughter also set personal highs by averaging .238 with five homers and 32 RBI. Dolly Vanderlip, the third-year right-hander who pitched the two previous season with Fort Wayne, ranked second in the league with her 2.40 ERA, and she posted an 11-6 record. Kidd’s 2.91 ERA ranked fourth, giving South Bend three of the circuit’s top four pitchers in the 94-game season, making 1954 the only year when AAGPBL teams played less than 108 games. Ironically, while the quality of baseball on the diamond was improving, the league couldn’t attract enough fans to support the teams.

Kidd, like many other players, took the opportunity to play other sports in the offseason. She played basketball with the Rockettes of South Bend, also working in the area. She was asked to sign with Bill Allington’s baseball All-Americans, who, starting in 1955, barnstormed the country for three summers playing exhibitions against men’s teams. However, Marvin Kidd suffered his first heart attack in 1955, and Sue returned to Choctaw for a year to help run the family’s combined store and post office. In 1956, she returned to South Bend to work. Her father died in early 1960, and after a year, she made good on her promise to him to go to college. She completed the bachelor’s degree and, later, the master’s degree in physical education at Arkansas State Teachers’ College. Beginning in the fall of 1964, she returned to Indiana, where salaries were higher than in Arkansas, and she taught physical education in middle school and high school through the spring of 1989. She served for one year in Onward and the remaining twenty-four years in Logansport, and during the first seventeen years, she also coached basketball, volleyball, track, and field. After her coaching years, she taught elementary school physical education and, for enjoyment, groomed dogs. Sue retired from teaching in 1989, divided her time between Logansport and Choctaw, continued the dog grooming business, and helped take care of the mother of an accountant friend during her friend’s busy tax season.

An exceptional female athlete, Kidd cherished her time in the league as well as the opportunities she received due to her athletic ability. A lifelong sports fan who loves Arkansas football and major league baseball, she recently observed: “Back in 1992, when they made the movie A League of Their Own, I did most of the pitching when they showed the league’s original players, because some of the women pitchers no longer had the arm strength, or they couldn’t last very long, or they couldn’t throw the distance with control. I was still in pretty good shape from teaching Phys Ed and playing with the kids in class on free days. I was also pitching in the background of the first part of the movie when Dottie Hinson [played by Geena Davis] entered the field. I wore a blue shirt, and I was only one to be wearing a white ball cap. I was on the mound pitching in that scene. I had been bucked off a horse just a few days before, so I couldn’t run much, but my arm was good.”

Sue Kidd’s enduring legacy will be with the historic All-American League: “I am very thankful for the chance I had to play pro baseball. I liked the experiences, the making of new friends, the traveling, and all the other opportunities that came from getting to play in the All-American League. Otherwise, I may never have got to do all the other things, like playing several years of basketball, finally going to college, making a career as a teacher, and coaching. Those six years of baseball were the most enjoyable times of my life. I give God credit for everything, because I always had faith I would get to play pro baseball, and it came to pass.”

Glenna Sue Kidd passed away on May 4, 2017, at age 83 in her hometown of Choctaw, Arkansas.

Sources

Material for this article came primarily from two sources: the book by Jim Sargent and Robert M. Gorman, The South Bend Blue Sox: A History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Team and Its Players, 1943-1954 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2012); and interviews with Sue Kidd. I spoke with Kidd and exchanged e-mails on numerous occasions both for our Blue Sox book as well as for my forthcoming book of AAGPBL interviews. I conducted the most detailed interview with her on September 6, 2010. Kidd’s statistics, reproduced on the back of her Larry Frisch baseball card, were derived from the summary sheets prepared on a yearly basis for the All-American League by the Howe News Bureau, copies in AAGPBL Files, Center for History, South Bend, Indiana. In addition, the AAGPBL web site provides a wealth of information about teams, players, and more; see http://www.aagpbl.org/

Full Name

Glenna Sue Kidd

Born

September 2, 1933 at Choctaw, AR (US)

Died

May 4, 2017 at Choctaw, AR (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.