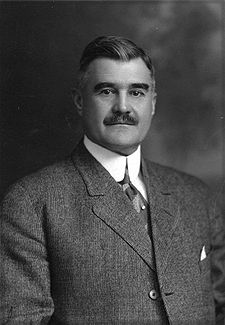

Tom Lynch

Connecticut native Tom Lynch shares a baseball distinction with one other man: He and John Heydler were the only major league presidents who earlier in their career were major league umpires. Lynch was president of the National League from 1910 to 1912. He had been a National League umpire from 1888 through 1902. His immediate predecessor as NL president, John A. Heydler, umpired from 1895 through 1898. (Heydler was actually acting president in 1909. He held the job in his own right from 1918 through 1934.)

Connecticut native Tom Lynch shares a baseball distinction with one other man: He and John Heydler were the only major league presidents who earlier in their career were major league umpires. Lynch was president of the National League from 1910 to 1912. He had been a National League umpire from 1888 through 1902. His immediate predecessor as NL president, John A. Heydler, umpired from 1895 through 1898. (Heydler was actually acting president in 1909. He held the job in his own right from 1918 through 1934.)

It’s hard to say which job – umpire or league president – was tougher. The 1890s were not a pleasant time for baseball umpires. For one thing, they worked alone and had to cover all three bases as well as home plate. This led the National League to hire a world-class sprinter as an arbiter. Another one, Tim Hurst, was a professional race walker. Also, the pay was not good. Umpires made only about $1,250 a year. Even scrub players riding the bench made more than that. Then there was the abuse. Players, fans, and club officials heaped it on the umps. Usually it was verbal, but sometimes things got physical.

The Irish dominated the rosters of the clubs that decade. Many of the umpires, as well, were fellow Hibernians. In addition to the aforementioned Lynch and Hurst, Silk O’Loughlin and Hank O’Day were among the most prominent.

Thomas J. Lynch was born in 1859 in New Britain, Connecticut, and grew up on Sexton Street in the city. His parents, Patrick and Mary, were Irish immigrants. As was the custom, they had a large family. Lynch had six siblings. He played a little ball in the minor leagues before turning to umpiring. He started out in the mid-1880s, working in the New England League for a year, then moving to the Eastern League. National League President Nick Young hired Lynch for the 1888 season. Young was not all that discriminating in his hiring practices. He would hire some men sight unseen and many were inexperienced, but Lynch was known for his honesty and integrity. He served the league well but after ten years, battles with teams such as Baltimore and Cleveland were starting to burn him out.

Matters came to a head on August 6, 1897. The Baltimore Orioles were playing Boston at the Red Stockings’ South End Grounds. In the eighth inning, Lynch ejected Joe Kelley and Arlie Pond from the Baltimore bench. Dirty Jack Doyle, the first baseman, called the umpire a big stiff. Then, after the inning ended, Doyle threatened Lynch, telling him that he’d get trimmed in Baltimore. Lynch gave him the heave-ho. The player started barking at him and Lynch nailed him between the eyes. Doyle responded by head-butting Lynch, closing the ump’s left eye. The police and other players had to break the pair apart.

Lynch went home to New Britain to recover. He had choice words for the Orioles, saying that their antics would “bring a response in the shape of a bullet if they were off the field.” Embarrassed, he tendered his resignation. But Nick Young would not accept it. It was a tough era for umpires. Tim Hurst had officiated at a game in Cincinnati in which a fan tossed a beer stein at him. He tossed it back into the crowd and it struck and seriously injured another fan. Hurst wound up in jail.

Lynch stayed on for another year but got tired of the guff he received from New York Giants owner Andrew Freedman, a man detested even by most of his fellow owners. Lynch resigned in 1899 and returned to New Britain to manage the Russwin Lyceum Theater. This was a vocation he already had during the offseason. He would now pursue it full time. Retrosheet.com shows that he umpired three games in 1902. The National League tried to call him back in 1903, but he didn’t bite. Lynch also ran a bill-posting business, was a prominent Elk, and was a New Britain parks commissioner. In 1909, he helped manage the New Britain Perfectos of the Connecticut State League. He received mixed reviews for that job.

Baseball owners in those days were a cantankerous lot, agreeing on little. Much of their venom was directed at the National League president, Harry Pulliam. The stress was too much for Pulliam and he shot himself to death in the summer of 1909. John Heydler, who was secretary-treasurer of the league, replaced him on an interim basis. The Sporting News and Cincinnati Reds president Gary Hermann mounted a campaign to elect Heydler permanently. Chicago Cubs owner Charles Murphy despised Heydler and backed John Montgomery Ward as a candidate. But Ward was unacceptable to American League president Ban Johnson, with whom the National League president served on the governing National Commission. Johnson and Ward had been embroiled in a feud for almost a decade, going back to the formation of the American League, over Ward’s representation of players against the owners.

Voting lasted a week. The National League owners were deadlocked, 4 to 4, between Heydler and Ward. Robert Brown of Louisville was another candidate. Tom Lynch was put forward as a compromise candidate by New York Giants owner John Brush. Brush’s reasoning was that the president’s main task was to supervise the umpires and so Lynch would be well suited for the job. Brooklyn’s Charlie Ebbets withdrew Ward’s name, Stanley Robison, owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, withdrew Brown’s name and Lynch was elected. To celebrate, a Hartford bartender created a concoction in his honor. The Tom Lynch was essentially a gin and juice with a dash of a secret ingredient.

Lynch was the second Connecticut native after Morgan Bulkeley to become National League president. Harold Seymour wrote that Lynch wasn’t known for diplomacy during his tenure. He was occasionally farsighted. In 1911 Ban Johnson wanted to price the movie industry out of the World Series business. But Lynch priced the rights at a (then) reasonable $3,500. He was also pro-umpire. Lynch would fine Bill Dahlen for all his run-ins with Lynch’s umpires. He also tried to fine Dahlen’s boss, Brooklyn president Charles Ebbets, for sending players to the minor leagues without putting them through waivers. But Ebbets refused to pay and was backed by the other team presidents.

Every year there was a cry for Lynch’s ouster. In 1912 a cabal was formed to get rid of the former umpire. Ebbets was still upset over Lynch’s attempts to fine him. Barney Dreyfuss of Pittsburgh didn’t trust John Brush, and Lynch was a Brush man. Garry Herrmann still wanted his friend Brown in office. Philadelphia’s Horace Fogel was also a foe. But this coup attempt failed when Fogel was driven from the National League after he railed against umpires and Lynch, accusing them and St. Louis Cardinals manager Roger Bresnahan of conspiring to let the New York Giants win the pennant.

In 1913 Lynch’s foes succeeded. He was ousted as National League president and replaced by Pennsylvania Governor John Tener. It was rumored that Lynch was offered the presidency of the upstart Federal League but did not accept. He retired to his native Connecticut. Lynch became ill in early 1924 and died at Hartford Hospital on February 27. He was 65. After a funeral Mass at St. Mary’s Church in New Britain, he was buried in that city’s Fairview Cemetery. Two years later, the world champion Pirates were in Hartford to play an exhibition game. They took a short detour to New Britain to lay a wreath on Lynch’s grave.

February 2011

Sources

Boston Globe

Hartford Courant

New York Times

The Sporting News

Eldred, Rich “Umpiring in the 1890s” In The Perfect Game Alvarez, Mark Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1993

Fleitz, David The Irish In Baseball: An Early History Jefferson: McFarland, 2009

Lamb, William “The Ward v. Johnson Libel Case: The Last Battle of the Great Baseball War.” In Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Volume 2, Number 2

Seymour, Harold Baseball: The Golden Age New York, Oxford U. Press, 1971

Full Name

Thomas J. Lynch

Born

, 1859 at New Britain, CT (US)

Died

February 27, 1924 at Hartford, CT (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.