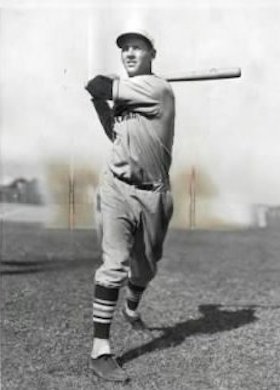

Tom Winsett

John Thomas Winsett was the son of a farming couple, John D. and Ida M. Winsett, in McKenzie, Tennessee – a small community of just over 1,300 people, 120 miles due west of Nashville. He was born on November 24, 1909, the fifth child in the Winsett family. Jack (the nickname he himself reported, and one often used in the newspapers of the day) attended the McKenzie schools through high school, then two years at Bethel College in McKenzie.

John Thomas Winsett was the son of a farming couple, John D. and Ida M. Winsett, in McKenzie, Tennessee – a small community of just over 1,300 people, 120 miles due west of Nashville. He was born on November 24, 1909, the fifth child in the Winsett family. Jack (the nickname he himself reported, and one often used in the newspapers of the day) attended the McKenzie schools through high school, then two years at Bethel College in McKenzie.

At Bethel, he played on the football team. He was 6-feet-2 and 190 pounds.

He was a pitcher when he first broke into baseball, but too good a hitter to keep on the bench between starts. He threw right-handed, but batted left.

He began his professional baseball career at 19 in 1929 with Lake Charles in the Class-D Cotton States League. Actually, the team had been based in Meridian, Mississippi, but moved to Lake Charles on June 17. It finished in last place. After hitting .284 with four homers in 22 games for Meridian/Lake Charles, he joined the Mobile Bears and hit safely 16 times, including three home runs, in his first five games. For Mobile, he hit .346 in 78 games. Winsett earned himself a headline in some papers around the country when his contract was sold to the Boston Red Sox on August 29.1

The Red Sox wanted him, the Biloxi Daily Herald reported a little clumsily, “because the Boston officials need outfielders and plenty of them — if they are good – they have had enough bad ones lately.”2 It had certainly been the case that the Red Sox had hardly ever escaped last place throughout the decade of the 1920s.

Winsett was a little late reporting to spring training at Pensacola, so he could wrap up more of his studies in medicine.3 The team planned to farm him out but he gave them pause when he hit a long home run on March 27, “far out into the gulf at Legion Park…Any player who can hit the ball gets [manager Heinie] Wagner‘s vote.”4 He was a raw talent, “an inexperienced outfielder. Sometimes he offers at bad balls. He is not always sure where he should throw that ball when it comes to him with men on bases. But the way he hits that ball has been the subject of more than a few whispering huddles on the part of Wagner and right-eye Jack McCallister.”5

A bases-clearing 10th-inning double on April 5 in Indianapolis helped his cause. He started the season with the Red Sox but had just that one at-bat in his April 20, 1930 debut at Boston’s Braves Field, where an ordinance required the Red Sox to play their Sunday games through May 1932. With the Athletics leading, 5-3, Winsett pinch-hit for pitcher Danny MacFayden in the bottom of the ninth. He struck out on three pitches, “taking a healthy but belated swing at all three, which were fast ones.”6

It was his only plate appearance in the majors in 1930. On April 25th he was optioned to St. Paul.

He wasn’t with the Saints for long. After just seven games (going 1-for-5), he was acquired by the Dallas Steers on May 21. He only played in four games for Dallas (2-for-16 at the plate), and by mid-June was with Mobile, where he played in 74 games, hitting .299. Two of his eight homers were hit in the August 13 game against Birmingham.

The Red Sox brought him back to Pensacola in 1931 and he impressed them in the exhibition season. “Nobody else hits them as Winsett does,” wrote Whitman. He was “the most talked-of young man” in early spring training.7 He was said to have developed more poise as well.

New manager Shano Collins tried him out at first base (Melville Webb of the Boston Globe wrote that Winsett “although showing no special class as an outfielder, has been batting like a wild man.”)8 Though he looked good his first day, the experiment only lasted a few days before he was shifted back to his customary right field. In fact, the day after Winsett’s initial trial at first, hot outfield prospect Gene Rye fractured his wrist and the Sox needed an outfielder more than a first baseman. The day Rye broke his wrist, the Globe reported that Winsett “had a hard time of it playing first base.”9

Winsett hit well, his third homer of the spring earning him an eight-column headline in the March 31 Globe. By this time, he was playing left field. He made the team – and made quite an impression in his first 1931 at-bat, on Opening Day at Yankee Stadium. There were a reported 70,000 fans at the game. Two players hit homers – Babe Ruth for New York and, pinch-hitting in the top of the eighth, Tom Winsett for Boston. Winsett’s drive off Red Ruffing just snuck in; it traveled past the right-field foul pole in fair territory, then arced foul. It was a homer, nonetheless, and closed the gap to 6-3, Yankees, the final score.

Winsett’s fielding deficiencies limited him to mostly pinch-hitting, but he had ample opportunities to contribute with his bat. His first 22 appearances were as a pinch-hitter, though all he had to show for it at that point were four RBIs and a .182 average. There was a stretch in mid-July when he started several games in left field, but by season’s end he had 81 plate appearances with 15 hits, seven RBIs, and a .197 batting average that had been hurt by a disappointing 21 strikeouts. Clearly an impatient hitter, guilty of swinging at bad pitches, he drew only four walks. During his relatively little time in the outfield, he handled 14 chances without an error and had one assist.

On December 2, the Red Sox traded Winsett and utility first baseman Jack Smith to the International League’s Buffalo Bisons for left-handed pitcher John Michaels.

Winsett’s 1932 season was spent with Buffalo and it was a good one; he played in 109 games, hit 18 homers, and batted .351, making the International League All-Star team. Bob Quinn of the Red Sox still held an option on Winsett and in December 1932, the Boston Herald reported that Quinn had been “offered big money” for him by other major league clubs.10 Quinn wanted to keep him, though, and see how he fared in spring training with the Red Sox at Sarasota, under incoming manager Marty McManus.

He had another good spring, with a booming home run over the right-field fence early in the exhibition season and a three-hit game, two of them driving in runs with two outs, late in March. It was said his “International League experience has matured him a lot.”11 By the time the season began, Quinn had sold the Red Sox to young Tom Yawkey. Winsett appeared in six April games, starting two games in right and one in left. If he’d matured, it didn’t show in plate discipline – he struck out six times in 12 at-bats. He managed one base hit, a single. He had just one fielding chance and handled it without an error.

On May 12 the Red Sox optioned him to the Montreal Royals. He took the 4:40 train out of town.12 He hit 18 homers for the last-place Royals, though his .283 average wasn’t as good as his time with Buffalo in the same league the year before. Out of options at this point, the Red Sox traded him (and John Michaels) to Rochester for lefty Fritz Ostermueller.13

Quinn felt that Winsett may have lacked sufficient ambition and self-confidence to succeed. Others more frankly mentioned ambition. As Quinn later put it, “He has the physical make-up all right but my personal observation is that Winsett must acquire a big league attitude. He knows he can spank minor league pitchers but he isn’t so sure of himself when he faces the big shots. Winsett’s success up here depends on Winsett.”14

Rochester was in the St. Louis Cardinals system, and Winsett had a very good year in 1934, hitting 21 homers and batting .356.

Once again he excelled in spring training and he started the 1935 season with the Cardinals and got off to a very good start, going 6-for-12 through May 11. He was batting .500, but four days later the Cardinals outrighted him to Columbus on cut-down day. He never appeared in another game for St. Louis.

With Columbus, a Cardinals farm team, he excelled, hitting American Association pitching for 20 homers and a .348 average in 1935, followed by an extraordinary 1936, hammering out a league-leading 50 home runs (21 in the month of June alone)15 and hitting a league-leading .354. He also led the league with 154 runs batted in. Winsett’s biggest day was June 13, 1936, when he hit three homers, drove in nine runs, and scored six runs himself. What more could one want? The knock was still his fielding – witness his remarks on handling ground balls reported in late June: “I know how to do it, but darn the luck when the time comes to act, I forget.”16

If there were ever a player better suited to become a designated hitter, it might have been Winsett. But, that said, he also had trouble with major league pitching.

The Brooklyn Dodgers wanted to take their chances with him and on August 1 purchased his contract from Columbus, to report to Brooklyn at the end of the American Association season. The deal was reported as straight cash at the time ($30,000), but later (in December) the Dodgers sent three players to the Cardinals: Frenchy Bordagaray, Dutch Leonard, and Jimmy Jordan.17

Winsett joined the Dodgers at the end of the season, playing in 22 September games, all but one of them as a position player. He didn’t hit for a high average (.235), and only homered once, but he was productive at the plate, driving in 18 runs in the 22 games. There was, however, said to be one game where he let the ball get over his head and played “three singles into two home runs and a triple.”18 Purportedly, Brooklyn pitcher Van Lingle Mungo was infuriated at losing the game and “tore the clubhouse apart” before calming down and sending a telegram to his wife: “Pack your bags and come to Brooklyn, honey. If Winsett can play the outfield in the big leagues, it’s a cinch that you can, too.”19

Winsett truly did see over his head playing in the majors at the time. He could hit the ball but when it came to using his feet to run – either on defense of offense – he committed blunders. The September 13, 1936 Brooklyn Eagle told of how his home run and game-winning two-RBI single had won the first game on September 12, 9-8. In that game against the visiting Cardinals, he “failed to catch balls hard hit by Don Gutteridge and Art Garibaldi and they rolled for home runs inside the park.” The paper focused more on his fielding lapses than his heroics, and acknowledged that “both chances were extremely tough but the clients chose to blame the rookie and complained loudly.”20 On September 22, as Brooklyn dropped two games to the Boston Bees, sportswriter Tommy Holmes said that Winsett was fast afoot but not agile; he had trouble turning while running in the outfield. He had charged the Gutteridge ball that got by him back on the 12th, almost reaching third base before he was able to put on the brakes, turn, and retrieve the ball. As a baserunner, too, Holmes noted that in just two weeks with the ballclub, he’d managed to get thrown out four times at home plate when trying to score from second on a hit to the outfield.21

He was the team’s regular left-fielder in 1937, hitting for a similar average (.237) in 118 games, but he drove in only 42 runs all season long. We can’t speak for range, but he played 100 games in left field, one in center, and even pitched one inning. His fielding percentage was .960, nine errors in 224 chances. The one time he pitched was on September 27, 1937. He was the team’s closer – if you want to call it that – in the day’s game at Baker Bowl against the Phillies. Philadelphia had a 9-3 lead after 7 ½, and Dodgers manager Burleigh Grimes let Winsett pitch the bottom of the eighth. He faced seven batters and gave up two runs on two walks and three hits (two of them doubles), but he finally did retire the side. Though he’d begun his career as a pitcher, this was the only time he pitched in the majors. (He worked in one minor-league game, too, for Jersey City in 1938.) The idea for him to pitch had surfaced the year before, Grimes telling a New York Post writer that the catchers on the Dodgers all knew he had a really good arm, a loose action, and a “blazing fast ball.” If he didn’t start to hit soon, Grimes allowed, they might try him on the mound.22

Tommy Holmes, writing in the Brooklyn Eagle, thought he figured out what Winsett’s problem was. If he had, it was probably too late for Winsett to adjust. Noting the vast difference between Winsett’s batting and slugging in minor-league and major-league ball, he wrote, “There isn’t and can’t be that much difference between a major league and the American Association.” He quoted an unnamed ballplayer as saying that Winsett always had the pitchers in the hole in the AA and they had to throw the ball over the plate, but (the article was headlined “Dawdling at Plate Seen as Root of Winsett’s Major League Ills”) in the big leagues the pitchers got the jump on him “and before he knew it he had two strikes.”23 This pushed him to go for bad pitches and did him in. He was apparently a sucker for high pitches and ones that were slow.24

Winsett spent most of 1938 at Jersey City. He started the season with the Dodgers and played 11 games in April – five in left, four in right, and two as a pinch-hitter. He pinch-hit in the May 1 game, the last major-league game in which he appeared. In his 12 games, he actually hit .300 and drove in seven runs, but on May 2, the Jersey City Giants purchased his contract from Brooklyn.

With Jersey City, he played in 132 games but hit for just .259. He had, however, regained his power stroke and hit 20 home runs. He was called up by the parent New York Giants in September but did not appear in any games.

Winsett played four more seasons – all in the minors – before World War II was on in earnest and he decided to join the effort. He was 32 years old and single, but not likely to be called, at least for quite a while. He elected to enlist and did so as a private in the United States Army Air Force on July 17, 1942, at New Orleans. In his last game before reporting for induction, he won a game against Atlanta with a pinch-hit in the eighth inning.25

How had he done in those final minor-league seasons? He moved around. In 1939, he began with Jersey City again, but with only three games under his belt there, he spent most of his time with Sacramento (22 games) and Columbus (67 games), both Cardinals farm teams. Combined stats for the three teams saw him hit .260 with 17 homers.

In 1940, it was Houston in the Texas League, Class-A1 ball (a notch down from Double A); he hit an even .300 with 18 homers. In 1941, he began with Rochester (15 games) but spent most of the season with the New Orleans Pelicans in the Southern Association (109 games, .307 with 16 homers). He began the 1942 season with New Orleans but after 73 games, hitting .266 – with only three home runs – he made the move to enlist. As a corporal, he was attached to the athletics and recreation of the basic training facility at St. Petersburg in 1943.26 By August, he was reported to have become a lieutenant.27 He was stationed in Hawaii by 1944 and his Seventh Army Air Force team won the Hawaiian Senior League championship. The team featured Joe DiMaggio, Jerry Priddy, Walt Judnich, Dario Lodigiani, and also a “sepia” player – pitcher Harold Harriston, “only Negro member on the 7th AAF baseball team.”28

Winsett served into 1946. Just days after the war was formally concluded, he married Dorothy Ruth Donahoe on September 7, 1945.

After the war, he became involved selling real estate as a broker for the Kemmons Wilson Realty Company. Winsett said his hobbies were fishing and photography. He and Dorothy had two or three children, but were divorced at the time of his death in Memphis on July 20, 1987.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Winsett’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Charlotte Observer, August 30, 1929

2 Biloxi Daily Herald, January 13, 1930.

3 Boston Herald, March 6, 1930.

4 Boston Herald, March 28, 1930.

5 Ibid.

6 Boston Globe, April 21, 1930.

7 Boston Herald, February 24, 1931.

8 Boston Globe, February 27, 1931.

9 Boston Globe, February 28, 1931.

10 Boston Herald, December 23, 1932.

11 Boston Globe, March 10, 1933.

12 Boston Herald, March 13, 1933.

13 Boston Herald, October 26, 1933.

14 Bill McCullough column in unidentified newspaper clipping dated November 28, 1936 and found in Winsett’s Hall of Fame player file. The mention of ambition is found in an undated Brooklyn Eagle clipping in Winsett’s file.

15 The Sporting News, July 9, 1936.

16 Omaha World Herald, June 27, 1936.

17 The New York American cited the $30,000 figure in its August 2 edition.

18 Stan Lomax, unattributed March 6, 1937 clipping found in Winsett’s Hall of Fame player file.

19 Arthur Daley, New York Times, February 9, 1969.

20 Tommy Holmes, Brooklyn Eagle, September 13, 1936, 40-41.

21 Tommy Holmes, Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 1936: 20.

22 Stanley Frank, New York Post, June 18, 1937.

23 Brooklyn Eagle, March 29, 1938.

24 Brooklyn Eagle, May 24, 1937.

25 Biloxi Herald, July 17, 1942.

26 The Advocate (Baton Rouge), March 5, 1943.

27 New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 25, 1943.

28 New York Amsterdam News, September 9, 1944.

Full Name

John Thomas Winsett

Born

November 24, 1909 at McKenzie, TN (USA)

Died

July 20, 1987 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.