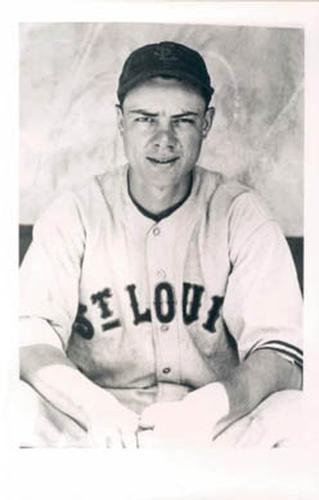

Angelo Giuliani

He could have been nicknamed “Tugboat” or, for that matter, “Giuliani the Magician,” for the many varied and workmanlike roles Angelo John Giuliani played during his life dedicated to baseball. From a fledgling full-time backstop in the minors to sharp-eyed scout in the majors, Giuliani’s resume was a convincing testimonial of a player who, having proven his talents, wanted to make sure others had the same opportunities he did.

He could have been nicknamed “Tugboat” or, for that matter, “Giuliani the Magician,” for the many varied and workmanlike roles Angelo John Giuliani played during his life dedicated to baseball. From a fledgling full-time backstop in the minors to sharp-eyed scout in the majors, Giuliani’s resume was a convincing testimonial of a player who, having proven his talents, wanted to make sure others had the same opportunities he did.

The seeds were sown early for Giuliani’s initiation into a life of baseball. He was born November 24, 1912, his home within blocks of St. Paul’s Lexington Park, which hosted the American Association’s St. Paul Saints. The son of Italian immigrants, Giuliani was yet an infant when his grandfather, also named Angelo, became ill back in Italy, forcing his 35-year-old expectant mother, Madeline, to leave for her homeland to tend to her father’s health. She took little Angelo along, leaving her husband Giocondo home alone. The birth of Angelo’s only sister, Agnes, during the Great War would be a blessing, but the armed conflict in Europe dashed any immediate hopes of returning stateside.

In Peter Golenbock’s book, The Spirit of St. Louis, Giuliani goes into some detail about his family’s past:

“My father was in the statuary business. He and his three brothers formed the Giuliani Statuary Company in the late 1890s in Tuscany, Italy, which is world famous for artists and sculptors. . . . When I was thirteen months old, my mother got a letter from Italy that her father was in his last days. My mother and I took a steamer to Genoa, and we arrived in time for her father to have his eternal rest. But unfortunately, in 1914, World War I started, and we were trapped there until it was over in 1918. The Germans were invading. We went to my grandpa’s place in Tuscany, and when I was six and seven, I stomped grapes in the fall.

“When the war ended, we returned to St. Paul, and I’ll never forget the sight of seeing the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. We took the train up to West Point and then crossed over, so I got to see Niagara Falls. As the train went over the bridge above the falls, I remember my mother saying to me in Italian, ‘Angelo, Angelo, guarda acqua.’ ‘Look at the water.’”

To pass the days during his family’s absence, the 35-year-old Giocondo, a statuary artisan, became enamored with the flannel-clad St. Paul Saints stirring excitement down the street. By the time his son and wife returned from their sojourn in the old country, he’d steeped himself in the exciting American tradition of baseball, according to writer Brad Zellar. Once Angelo returned from Italy at the age of seven it didn’t take long for his father to ignite the baseball spark in the impressionable youngster. “Because of the proximity to Lexington Park, my father could hear all the screaming and yelling that went on down there and of course that will make a fellow curious. He started going down there to investigate and became a tremendous fan,” Giuliani told Zellar in 1996.

Early on, the diminutive Giuliani showed a high level of imaginative innovation as he sought to incorporate baseball into his juvenile world. He told Golenbock, “I used to play a game against the steps with a rubber ball. ‘The Bambino’ [Babe Ruth] was hitting home runs. I would throw a rubber ball against the steps, have a lineup, and Babe Ruth would hit a home run every time he came to bat. My mother would hear the noise of the ball against the steps, and she’d say in Italian, ‘Angelo, what’s all the noise?’ And I’d say, ‘The Bambino hit another home run.’”

The sandlots of St. Paul became a second home to the boy. One can just imagine the cluttered bedroom of such a diamond-minded lad, littered with pennants and peanut wrappers, his gritty old mitt and cap at the ready while the closet became stuffed with his other playground paraphernalia. Angelo attended his first ball game at the age of 12, watching the American Association champion St. Paul Saints take on the pride of the International League, the Baltimore Orioles, during the 1924 Little World Series at Lexington Park. Giuliani would later reflect, “Alphonse Thomas was the winning pitcher for Baltimore that afternoon. Twelve years later he was my first major league roommate with the St. Louis Browns.”

Giuliani grew up in St. Paul’s Third Ward, an ethnically diverse neighborhood. It was quite a trek from the family home to Summit Avenue, where Angelo attended St. Luke’s Catholic School. But the youngster wasn’t complaining. As the catcher for the school’s ball team, the St. Luke Silkstocking Lads in the Parochial League, he took pride in being a kid from the city’s working class enclaves. “Here I was, an Italian kid from the shadows of the gas tanks, playing ball with all these Summit Avenue boys. You know who also was a St. Luke’s boy, don’t you? Paul Molitor. Of course that was well after my time,” Giuliani told Zellar.

In 1927, while fellow Minnesotan Charles Lindbergh was preparing to set his record flight across the Atlantic, Giuliani was preparing to enter Cretin High School. But Father W. Joseph “Shorty” Gibbs intervened. Athletic director at the St. Thomas Military Academy, Gibbs promised Angelo free tuition and books; besides, Cretin had no athletic program at the time, according to Zellar. Giuliani related, “My father was of the impression that this was a tremendous offer. Money was tight in those days. Little did we know that I would have to buy my own uniform, and that the uniform would cost more than the tuition and books combined.”

In 1928 Giuliani was part of a highly successful prep-school nine. The State Academy championship went to the St. Thomas Cadets, as they were known, after a 12-game season. Their young catcher may have had something to do with it, as “Angie” demonstrated offensive mastery with a .556 batting average. As a member of the American Legion Junior squad out of St. Paul that summer, Giuliani would partake in contests around the region, getting both the experience and exposure that would be invaluable to him during his development. Many of the same players from the academy were on the Legion team. The recipe was working as they took the Juniors championship for 1928.

It wasn’t long before the 5’11”, 175-pound receiver was drawing the attention of the owner of the St. Paul Saints, Bob Connery. After attending St. Thomas College in St. Paul, Angie was brought into the fold during the 1931 season, assisting on the sidelines well before he officially entered the field of play in the American Association.

In 1932 the 19-year-old officially joined the Saints. During spring training camp at Mineral Wells, Texas, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported that Giuliani was handling the receiving chores during most of batting practice and handling things well. “This young St. Paul youth is making quite an impression with President Connery. He took the youngster aside the other day and instructed him on how to shift with the pitch and the youth picked it up in a hurry,” wrote Lou McKenna, Saints secretary and business manager, for an article in The Sporting News. Offensively he was making strides, as well. “He is driving the ball hard, too, and Mr. Connery has hopes that the youngster will develop into a good catcher. He will make an effort to place the St. Paul youth out for seasoning. The St. Paul club will have to pay a part of Giuliani’s salary if placed out but Connery is willing to do this to keep a string on the youngster.”

With the exhibition season winding down, Angie had a great game against Dallas, getting three hits in five at-bats and driving in five runs, as the Saints trumped the Steers, 21-4. According to McKenna, “He [Giuliani] looked like a finished workman behind the bat, too. He shifted remarkably well on the wide pitches and he had a line of chatter that kept his mates on their toes and attracted the attention of the Dallas bugs.”

As the week progressed, others chimed in. St. Paul outfielder Cedric Durst claimed Giuliani was the “finest looking youngster he ever saw,” according to McKenna’s report. Said Durst, “He’s one of those naturals. I don’t see how he can miss unless he’s injured.” Paul “Pee-Wee” Wanninger, considered a “good baseball judge,” had praise as well. “If they’ll put him out to get some experience he is likely to develop into a star. But often a player can be ruined by sticking him on the bench. Giuliani seems to have everything. He is cool under fire and he showed me plenty of ability in the two games he worked.”

In his first official appearance in a league game, he cracked a double in a pinch-hitting performance, standing in for Harold Elliott in the seventh inning of Louisville’s home opener on April 14, 1932 at Parkway Field. It was one of five hits for the Saints that day, as southpaw Archie McKain blanked the visitors, 12-0. The Saints would catch up with Louisville in the end, however, as the Colonels finished the season in eighth place, the Saints one notch ahead.

Appearing in 50 games defensively the right-handed batter had 196 at-bats in 80 games, hitting .276 with two home runs. He also fielded well, with a .989 fielding percentage. Manager Al “Lefty” Leifield’s team started poorly, causing Leifield to put Angie in as the starting catcher in lieu of Bob Fenner and veteran back-up catcher Frank “Pancho” Snyder against the Indianapolis Indians. It was the youngster’s first start of his professional career, taking place Friday, May 6 at St. Paul’s Lexington Park. Batting in the seventh spot, Giuliani started a Saints rally in the second frame by leading off with a single off right-hander Archie “Iron Man” Campbell. In the third, he made what St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter Jim O’Phelan described as “one of the best defensive plays of the game when he took in Campbell’s towering foul fly.” The Saints lost by a run despite a four-run ninth-inning rally, and their troubles continued.

The St. Paul community put their “favorite son” on a pedestal. On May 29, 1932, the prospect was honored at Lexington Park by a group of fellow Italians. In a ceremony before the game Angie was presented with a gold watch and charm, according to a report in The Sporting News. Although Giuliani was the first St. Paul boy brought up by Connery, he was not the first local Saint. That distinction fell to Hank Gehring, a spitball pitcher who began his American Association career in 1906 as a Minneapolis Miller, first taking the slab for St. Paul in 1908. Larry Rosenthal, another Connery find, was also a student of the St. Paul sandlots before joining the Saints in 1933.

Giuliani’s playing time took a nose dive in 1933, though he played well. Fenner, the Saints’ regular receiver, was having a career year at the plate, wrapping up the season with a .337 mark in 475 at-bats, including nine long balls. Giuliani posted a .326 mark for the fourth-place Saints under the ill-fated Emmett McCann (who committed suicide in 1937). In 144 at-bats Giuliani connected for 47 hits in 48 games, catching 41 games. He was showing a marked ability as a contact hitter, striking out only seven times while walking six. He had an errorless fielding record in 41 games behind the plate.

According to the website pitchblackbaseball.com, Angie had the privilege that year of facing the legendary Satchel Paige as a member of a traveling squad known as the American Association All-Stars (while it is likely this squad was sanctioned by the league, it was not an elected group of all-stars, per se) each player sporting the togs of his team. The Stars were invited to do battle with a conglomeration of semiprofessional elites out of Bismarck, North Dakota, headed up by Paige, on September 12, 1933. With the All-Stars trailing 15-0 in the eighth and final inning, Giuliani played a role in scoring against the great pitcher. Popping up to the infield, Angie knew he’d been foiled again, but Paige clownishly attempted a bare-hand pickup of the ball and muffed it. The next batter grounded to Paige, but he threw the ball into center field. The final score was Bismarck 15, American Association 2. The game was called on account of darkness.

While his playing time improved modestly the following season, Giuliani’s batting did not. Appearing in 64 games defensively in 1934, Giuliani’s average slipped to .259 in 220 at-bats. His fielding was a slightly sub-par .978 for his seventh-place Saints under new field boss Bob Coleman.

In 1935, perhaps Angie’s finest in the Association, he found new life. Under yet another freshman skipper, Marty McManus, Giuliani appeared in 109 games, posting a .277 average in 311 at-bats, topped off by 18 doubles and five triples. Roles were reversed, as it was Fenner’s turn to perform as back up. It was to be Angie’s St. Paul farewell, however, as the 23-year-old was headed for the majors.

Drafted by the St. Louis Browns of the American League, in 1936 Angie played a reserve role to Rollie Hemsley (116 games, .263 batting average), who was in his fourth season with St. Louis. Wearing the number 12 as a Brown, he accrued a batting average of .217 in 198 at-bats through 71 games under manager Rogers Hornsby. His numbers were unimpressive, but he’d achieved a dream.

Giuliani told Golenbock:

“The Browns drafted me from the St. Paul club in 1936. My first major league manager was Rogers Hornsby, the greatest right-handed hitter of all time, but not too great a manager at all times. I married my wife [Genevieve] in ‘36, my honeymoon year, and where did we train? In West Palm Beach. The reason was that Hornsby liked it. There’s a racetrack around there and horses, which he was addicted to. I loved the horses, but not to the extent of being addicted. I would see him, right at the finish line, especially in Louisville at Churchill Downs. He was addicted to the gambling of the horse races, no question about it. Later on, Judge Landis tried to ban that. He was one of them who he was shooting at.

“The George Washington Hotel was right on the intercoastal. You could see Palm Beach across the bridge, and the ocean, and it was a beautiful view, and after my wife and I checked in, got our things upstairs in the room, we were looking out at the beautiful view when the phone rang. The clerk said, ‘Sorry, Mr. and Mrs. Giuliani, you will have to move.’ I said, ‘Why? We just got here.’ He said, ‘Your manager doesn’t like this hotel.’ So we didn’t stay there, not even one night. We moved to a rattletrap farther inland, closer to the ballpark. That was one of my first experiences with Mr. Hornsby. What could you say? He was the manager. We had to follow his orders.”

On May 3, 1936, the young catcher’s path crossed with future greatness. In a game at Yankee Stadium, the Browns and New York Yankees tangled before a Sunday crowd. Big right-hander Jack Knott was on the hill for St. Louis when a young West Coast phenom name Joseph Paul DiMaggio, a future Hall of Famer, came to the plate for the first time as a major leaguer. Knott’s battery mate, Hemsley, was forced to leave the game early on after an errant throw struck him in the neck. Giuliani replaced him, putting him on the list of those who appeared in Joltin’ Joe’s first big-league game. Three years later he’d be watching as a member of the Washington Senators when Lou Gehrig gave his famous farewell speech at Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939.

After two early season appearances with the Browns in 1937, Giuliani’s contract was acquired by the Dallas Steers of the Class A-1 Texas League, as president Bob Tarleton bolstered his club’s hopes of a first-division finish. While this move appeared as a demotion for Angie, it turned out to be good for the youngster. Dallas, a Chicago White Sox farm team, was adding rising stars to its club, including former Saints pitcher Ralph Pate, giving a spur to the organization and boosting its chances to become competitive.

On June 12, Angie was behind the plate as veteran righty Fred “Firpo” Marberry tossed a no-hitter against the Galveston Buccaneers. Three players with St. Paul ties were starters for Dallas that night at Moody Stadium in Galveston. In addition to Giuliani, St. Paul native Mickey Rocco was playing first base for the Steers while former St. Paul Saint Joe Mowry (1936) was in center field. Angie played 107 games that year, establishing personal highs with 49 runs batted in (RBIs), 103 hits, 121 total bases, four stolen bases, and 380 at-bats. Giuliani was elected to the Northern squad of the Texas League All-Star team for 1937 along with fellow catcher Norman McCaskill of the Tulsa Oilers. By the end of the season, he was back with the Browns, appearing in a season total of 19 games, hitting .302 in 53 at bats.

In March 1938 Giuliani was purchased by the Washington Senators as insurance for their ace backstop and future Hall of Famer Rick Ferrell, who’d had an off-year due to injury in 1937. As reported by Denman Thompson in The Sporting News of March 31, 1938:

“On the face of things, the purchase of Giuliani was of minor importance to outside observers. The Senators, however, seemed to regard the move with almost exaggerated enthusiasm. They have supreme confidence in the catching of Rick Ferrell, but last year they had a taste of how hard it was to win when Ferrell was injured. They were not keen for another dose of the same medicine and with only rookies like Jake Early and Mickey Livingston in camp, the prospects were not inviting. Giuliani never has been a star, or even mildly outstanding. But, inasmuch as he is only 25 years old, Angelo may attain that status.”

According to the article, Elon “Chief” Hogsett, veteran left-handed pitcher, had this to say about Angie: “He’s a first-class receiver. He’ll be a big help.” Thompson reported that “nearly all of the Griffmen expressed satisfaction along similar lines. The newest of the Senators . . . attended Catholic University in Washington a few years ago. He was a promising back in football, but Angelo preferred to play baseball and Catholic had no varsity diamond team. So he quit school and hopped into professional ranks.” In fact, Giuliani broke his collarbone playing quarterback for the team, perhaps providing some impetus to the decision to end his gridiron days.

As a member of Bucky Harris’s Senators squad, Angie hit just .217 in 115 at-bats. But he showed considerable improvement in 1939, hitting .250 in 172 at-bats with 18 RBIs. Hogsett and Giuliani would eventually reunite on the 1941 Minneapolis team as both players enjoyed a resurgence of sorts in the American Association. They became lifelong friends.

It is worth noting that Giuliani played a role, albeit a minor one, in the history of how the player draft, or the “selective system,” as Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis called it, evolved during a 10-year period around this time. In this period there were new lows in the number of players being drafted out of the minor leagues, due in large part to the advancement of the farm system. As the use of the draft as a mechanism for developing player talent fell out of favor, the selective system seemed doomed to fail. The team roster limit was raised to 25 for the 1939 season, and this had a positive effect. In the fall of 1938, 18 players were drafted, nearly double the number from the year before, among them Giuliani.

Among all the players drafted since 1928 there were 26 yet in the major leagues, excluding those from the most recent draft, according to The Sporting News, and Giuliani was one of them. He was in good company: fellow catcher Ray Berres was on that list, and pitchers Whitlow Wyatt and Luke Hamlin were, as well, as was another fellow who left a large footprint in the annals of Minnesota sporting history, the multi-positional Dick Siebert who later had a long campaign as coach of the University of Minnesota Gophers baseball squad.

Giuliani was a member of another topflight group, major leaguers who were graduates of the American Legion Junior Leagues. In 1939 there were 46 players who’d established themselves among the youthful stars of the country playing Legion ball, gaining experience and honing their tools. Aside from Angie, the American League was represented by Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Bob Feller, and others. The National League had Phil Cavarretta, Augie Galan, Eddie Joost, Mickey Owen, and Mort Cooper.

During the spring of 1940, there were four catchers in the Senators’ camp: Ferrell, Jake Early, Al Evans, and Giuliani, who was referred to in The Sporting News as Ferrell’s “understudy.” Just before the start of the season, however, Giuliani was sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers for the waiver price of $7,500. But along with the cash came southpaw slab artist Al Hollingsworth. MacPhail told Griffith, “You take Hollingsworth for 30 days and if you can use him return the $7,500 I’m paying you for Giuliani. If you can’t use Hollingsworth [age 30], send him back to Brooklyn.” With terms like those, how could an agreement be avoided? It was later reported that the cash came directly out of MacPhail’s own pocket, perhaps a suggestion that MacPhail thought very highly of Angie’s abilities.

A few weeks later, a The Sporting News report questioned the move. “It is no bad ball player the Dodgers picked up. . . . On the Washington club he is rated one of the best backstops in the majors and an improved hitter. Tony never had much of a chance to catch with the Senators on account of the presence of Rick Ferrell. But last summer when Ferrell was hurt, Giuliani seemed on his way at last. He stepped into the lineup and not only caught superbly, but held up on offense. Tony was headed for a grand season when he also was shelved by an injured hand. By the time he recovered, the Senators were hopelessly out of the race and attention was given to developing rookie Early.” In 1940 Giuliani went to the International League’s Brooklyn farm at Montreal, where he played in 77 games as a Royal, hitting .253 with 40 RBIs in 233 at-bats. He made a lone appearance against the Dodgers on May 5.

In 1941 Angie appeared in three games for the Dodgers before being optioned to the Minneapolis Millers, a return to the American Association for the first time since 1935, although Giuliani was now a Miller. Having grown up in the shadow of Lexington Park, dyed in the wool of his hometown Saints, how must this new turn of events have sat? His allegiances were being tested. And to add insult to injury, certain quarters of the press were now referring to Angie as “Julio.” But perhaps that beats the moniker “Tony,” so flippantly assigned to him by Hornsby during his early days as a Brown. Neither was a name he’d been accustomed to.

After 37 games under Minneapolis manager Tom Sheehan, Giuliani was probably beginning to feel comfortably settled again; in 143 at-bats he was hitting .294 with six doubles. Then he was recalled by Brooklyn. Having felt poorly treated by general manager Larry MacPhail earlier that season, Angie refused to report and headed for his home in St. Paul. He thought about directing an appeal to the Commissioner’s office.

The Sporting News of November 27, 1941 listed Giuliani on the reserve list for the Montreal Royals, along with such names as Max Macon, Carl Furillo, and Van Lingle Mungo. Only days later, Millers owner Mike Kelley acquired Giuliani along with Mungo in a trade with Montreal for lefty hurler Joe Hatten. The deal took place during the winter meetings at Jacksonville, Florida. Kelley had had his sights on Angie, as his club had performed well while the catcher was on the team earlier in the year, then slipped out of contention after his departure. The Millers legend was reportedly “all smiles.”

Giuliani was back in the Twin Cities as a player. Upon his return home he quickly became involved in community doings, such as the local Hot Stove League broadcasts hosted by Stu Mann, sports editor of local radio station WDGY, sponsored by Conoco Motor Oil. But Angie wasn’t on solid ground. In a The Sporting News article dated March 26, 1942, Minneapolis journalist Halsey Hall said, “If Larry MacPhail allows Van Mungo and Angelo Giuliani to remain with the Millers, the [Millers’] battery hues become brighter. At this writing, disposition of their cases still awaited.” From this it is apparent Giuliani could yet be pulled back into the Dodger fold, despite the months-long expectation of being a Miller. It underscores the ballplayers’ tenuous life during this era and illustrates how an antagonistic relationship with a baseball power broker such as MacPhail could have serious repercussions on players’ personal stability and career.

Angie had his most active season as a Miller in 1942. While the club struggled under Tom Sheehan (76-78 in a tie for sixth place, 8½ games behind the front-running Kansas City Blues), Giuliani earned the full-time catcher’s job, appearing in 103 games at catcher and 12 more at first base. In 370 at-bats he swatted 14 doubles, drove in 43 runs, and scored 32 while hitting a lackluster .219. But it was enough to warrant the attention of Washington owner Clark Griffith.

The Washington Senators had been interested in reacquiring Angie’s services, and they were finally able to purchase his contract in November, a move precipitated by the entry of backstop Al Evans into military service. Giuliani’s return to Washington meant that Griffith could finally be satisfied that he had a catcher who could handle Dutch Leonard’s knuckleball. Said Griffith, “I have always had a high esteem for Giuliani as a catcher. I’ve wanted him back almost since the week I sold him.”

Writing for The Sporting News, Hall reported: “The 1942 draft brought another chance for Angelo Giuliani, one of the most popular players who ever wore a uniform in the American Association. Giuliani was selected from the Minneapolis Millers by Washington, where Clark Griffith always has liked him, and it marks his fourth advent into the major leagues. Married, 29 years old and in the top level of the minor leagues, Giuliani was solely a catcher all during his career until the past season, when injuries forced him to first base for a brief period. Although never a solid .300 socker, Gulie always hit respectably, especially in the clutch. He is a master workman back of the plate and this year made only three errors all season, the others coming when he was operating at the initial bag.”

Acquired for the sum of $7,500, Angie would back up Jake Early, appearing in 49 games for manager Ossie Bluege’s Senators in 1943. And it would be his final year in the majors. Due to his baseball-related back injury, Giuliani was not allowed into the military, being declared 4-F by the Selective Service board. As a result, he was available to continue his ballplaying career.

Mixing business with pleasure during his big-league swan song, Angie brought his racing pigeons from his home in Minnesota to Washington. There was some speculation that a competition might be arranged with Joe Engel, Griffith’s principal overseer with Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association, another former ballplayer who’d taken up pigeon raising, according to The Sporting News.

It wasn’t birds but Tigers who were caught aslumber during one of the final games of the 1943 season at Griffith Stadium. In the seventh frame of the October 2 contest, Dick Wakefield occupied third-base while Rudy York was on first. Joe Wood slapped a liner snared by the Senators’ Stan Spence in center. Wakefield bluffed a dash home, but on Spence’s peg to Giuliani, York lit out for second. George Myatt was there to receive the return toss from Angie, forcing York to retreat. After a run-down, Myatt applied the tag to York. Wakefield crept toward home, but a snap throw by Myatt to Giuliani froze him in his tracks. Angie then delivered the ball to Sherrard Robertson covering third and the delayed triple play was complete—a nice way to end his career in the major leagues.

During the spring of 1944, Angie was traded back to the St. Louis Browns in exchange for Rick Ferrell and cash. But the back pain he’d been enduring for years was enough to convince him to remain at home at his position working for the local archdiocese selling wine. Of course, Giuliani’s decision complicated things for the two clubs involved. St. Louis owner Don Barnes had the backing of Commissioner Landis in his demand for the return of Ferrell. Barnes acquiesced after Griffith offered to release 34-year-old outfielder Gene Moore to the Browns.

Not quite ready to abandon the game and his network of friends and associates, Angie became one of 28 scouts for the New York Giants in 1948, along with former Millers manager Tom Sheehan. Giuliani would scout for Detroit and Washington, staying with the latter team when it became the Minnesota Twins. With the Twins Angie is credited with signing 30 players, according to Golenbock. These included such key contributors as Kent Hrbek, Jim Eisenreich, John Castino, Jerry Terrell, and Tim Laudner, not to mention former Minnesota Gophers All-American pitcher Paul Giel. Adding to his lengthy resume, Giuliani was president of the Old Timers Hot Stove League in St. Paul, being succeeded at that position in December of 1954 by Milt Rosen.

But he couldn’t quite brush the diamond dust off his shoes. In 1949 he made a one-game cameo appearance with the American Association’s Minneapolis Millers. Then after seven years, he donned the Miller garb again on May 18, 1956, to serve as a short-term backup for Vern Rapp.

In 1961, at a time when many players would be picking up the golf clubs, Angie was put in charge of developing a program to develop youth talent for the Minnesota Twins. This became one of the most distinguished events in the career of this versatile and unselfish performer. According to his son, Tim, as many as 800,000 kids were infected with the baseball bug through Giuliani’s youth camps, including the Knothole Gang attendees at Metropolitan Stadium during which those kids who showed up for a clinic could stay and watch the Twins battle it out. Angie ran clinics and camps throughout the region, and also in Florida.

Angie died at the age of 91 on October 8, 2004. Genevieve Mary (Beiseker), his wife of nearly 60 years, had passed away in 1995. Among his closest friends was former pitcher Elon “Chief” Hogsett, whom he’d known for decades. Although more of a close acquaintance, former outfielder Larry Rosenthal was another compadre, someone who referred to him as “Bubblenose.” His many connections would have filled Metropolitan Stadium. But Angie’s memory lives on most intimately through his children, John, Michael, Timothy, and Mary Josephine. He was laid to rest at Resurrection Cemetery in Mendota Heights, Minnesota.

Angelo Giuliani was one of baseball’s ultimate ambassadors. Coming up through the ranks through various local programs, he learned the game at a time when potential ballplayers weren’t pampered and salivated over along every step of the way. Angie made it on his own, building upon his natural abilities to reach the highest level of professional baseball. It seemed he couldn’t live contentedly doing a 9 to 5 job. He was simply at his best when sharing his love of the game with others.

Author’s Note

An earlier version of this biography appeared in the book Minnesotans in Baseball, edited by Stew Thornley (Nodin, 2009).

Sources

http://ancestry.com.

http://baseball-almanac.com.

http://baseball-reference.com.

http://www.baseballlibrary.com.

Evans, Bob, e-mail of February 9, 2008.

Filichia, Peter, Professional Baseball Franchises, New York: Facts on File, 1993.

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis, New York: Avon Books, 2000.

Giuliani, Tim, telephone interview, February 13, 2008.

McNary, Kyle, e-mails of February 15-19, 2008.

Minneapolis Star-Tribune, October 9, 2004.

Nemec, Ray, Player Data Sheet.

http://pitchblackbaseball.com.

The Sporting News, various issues, 1932-61.

http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, various issues, 1936-37.

St. Paul Pioneer-Press, various issues, 1928-44.

Wright, Marshall. The American Association: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1902-52, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1997.

Zellar, Brad, “A Life in Baseball,” March 27, 1996, http://citypages.com.

Full Name

Angelo John Giuliani

Born

November 24, 1912 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

Died

October 8, 2004 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.