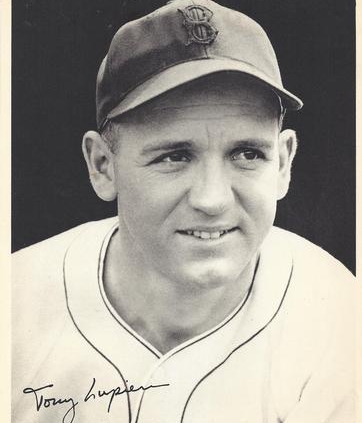

Tony Lupien

Ulysses “Tony” Lupien played just four full major league seasons, but he made a lasting impact on baseball through his pioneering player-rights efforts after World War II and his development of college players as baseball coach at Dartmouth College for more than twenty years.

Ulysses “Tony” Lupien played just four full major league seasons, but he made a lasting impact on baseball through his pioneering player-rights efforts after World War II and his development of college players as baseball coach at Dartmouth College for more than twenty years.

As a lefthanded-hitting first baseman in the 1940s, Lupien displayed remarkable bat control and Cal Ripken-like playing stamina. He was also an agile lefthanded-throwing first baseman who covered a wide fielding range, consistently ranking high in assists and double plays for first basemen. The 5′ 10″, 185-pound first baseman retired from the major leagues with a .268 batting average, rarely missing a game as his team’s regular first baseman (he appeared in 150 or more games in three of his four full seasons). Lupien was known as a contact hitter and tough strikeout. He whiffed just once in every 21 at bats and rarely hit into a double play. He still holds the Red Sox record for fewest double plays grounded into in a season (three in 1943).

All these playing attributes were not enough to offset Lupien’s lack of power hitting, which major league managers in that era often sought from their first basemen. Lupien consistently stroked singles and doubles, but connected for just 18 home runs in his 614-game major league career. His home run total was less than his career total of 30 triples. This lack of power hitting was a major obstacle for Lupien to overcome, especially when his first opportunity in the major leagues, with the Red Sox in 1942, was to fill the shoes of slugger Jimmie Foxx.

Lupien was born in Chelmsford, Massachusetts, on April 23, 1917. His parents, Ulysses and Jennie Lupien, named their fourth son after his father and grandfather – Ulysses John Lupien – a name that derived from his great-grandfather’s admiration for Civil War General Ulysses S. Grant.

At the time of Lupien’s birth, his father was a teacher and athletic coach at Lowell Textile School (now the University of Massachusetts at Lowell). In the 1920s, the family moved to Manchester, Connecticut, where Tony’s father had secured a more lucrative position as an industrial consultant for a textile mill. Lupien played football, basketball, and baseball at Manchester High School for three years, then continued his educational and athletic exploits for two years at the Loomis School in Windsor, Connecticut. After his graduation from Loomis, Lupien attended Harvard University, his father’s alma mater.

It was in the semipro leagues near his native Chelmsford that Lupien, then nicknamed “Cookie,” began to truly hone his baseball skills. While the family continued to live in Connecticut, each summer while in school, Lupien and his older brothers, Frank, Albert, and Theodore, returned to Chelmsford to stay with their grandparents and play baseball in the nearby Lowell Twilight League.

“No question about it, playing three or four nights a week in the semipro leagues really helped me,” Lupien remarked in a 1991 retrospective published in the Chelmsford Independent newspaper. “We must have played 75 to 100 games a season between school and semipro. Against tough competition. You just can’t play that much nowadays. We played all the time.”

Later, during his summers while studying at Harvard, Lupien played for the J.F. McElwain team, sponsored by the shoe manufacturer in Manchester, New Hampshire. “When I played with McElwain, you never knew if your position on the team was safe,” Lupien recalled in a 1992 article about his motivation to excel on the diamond. “There were lots of college players like myself, but also a lot of ex-minor leaguers. Guys would drift through town after being let go and try to hook on with the local semipro team.”

Lupien really blossomed as a baseball player at Harvard, under the tutelage of coach Fred Mitchell. He led the league in hitting in both his junior and senior years, in 1938 and 1939, clubbing for a .442 average as a senior.

Upon graduation from Harvard, Lupien signed with the local major league team, the Boston Red Sox, which assigned him to its Scranton, Pennsylvania, farm team in the Class A Eastern League for the balance of the 1939 season. Playing in 83 games in his first professional season, Lupien hit .319 and earned all-star honors.

In Scranton, Lupien also acquired his lifelong nickname of Tony, the result of a promotion at the Scranton ballpark for an Italian night. The promoter thought it would be a great idea for Scranton to field an all-Italian infield for the game and asked Lupien if he was Italian. “I told him, ‘No, but I eat spaghetti. Hey, just call me Tony.’ The name stuck with me,” the French-Canadian Lupien recalled.

His efforts in Scranton secured Lupien a promotion to the Little Rock, Arkansas, team in the Southern Association for the 1940 season. He labored through a hot summer in 1940 on a dismal team piloted by a manager native to the South who didn’t cotton to a college-educated ballplayer from the North. “The Red Sox sent me to Little Rock in 1940. It was one of the goddamnedest experiences a man ever had,” Lupien, with his characteristic bluntness, told Peter Golenbock in his book Fenway: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox. Of Little Rock manager Herb Brett, a Southerner, Lupien remarked, “He hated Northerners, hated college people, and hated Catholics. Of course, he hated me.”

“We lost 105 ball games that year. In August, we played fifty games – twenty doubleheaders and ten singles. This was rough going,” Lupien remembered. He endured not only the hot, humid summer weather in the South but also the temperamental outbursts and verbal abuse by the hard-drinking Brett, who seemed uninterested in winning ball games or developing players. Lupien learned endurance that summer, playing in nearly all the Travelers’ games while pounding out a .307 average under less than optimum playing, travel, and heat conditions that he hadn’t ever experienced in the North.

Despite the tribulations of that season in Little Rock, Lupien earned a September call-up to the Red Sox. He responded by collecting nine hits in 19 at bats for a .474 average in ten games in his first stint in the majors. Lupien made his major league debut on September 12, 1940, in Cleveland before a Thursday afternoon “crowd” of 1,000 in the Indians’ cavernous 80,000-seat lakeside stadium.

“First sacker Ulysses Lupien, the former Harvard captain, up from Little Rock, made his big league debut today,” the Boston Herald reported the next day of Lupien’s first major league at-bat, against Cleveland pitcher Mel Harder. “It wasn’t the happiest setting for him to make his bow. But the left handed lad went in to pinch hit for Emerson Dickman in the fifth, with one on and two out, and cut at the first pitch, an inside curve which went foul and was caught by first sacker Beau Bell.”

With Jimmie Foxx still the regular first baseman for the Red Sox in 1941, Lupien spent that season at Louisville in the American Association, then Class Double A and the highest level in the minor league system. Foxx, at the age of 34, was slowing down, but the righthander could still stroke home runs in the friendly confines of Fenway Park, with its nearby left field wall. Foxx, who had collected his 500th career homer ten days after Lupien’s first major league game in September 1940, stroked 36 homers in the 1940 season and 19 more in 1941.

Lupien had another excellent minor league season in 1941, as the Colonels challenged for the championship. Lupien hit .289 for Louisville, which lost in the final round of the playoffs to Columbus, a performance that earned him a place on the Red Sox roster for the 1942 season.

Foxx was still a fixture at first base in 1942, so Lupien rode the Red Sox bench for the first two months of the season. Then, on June 1, the Red Sox announced that the team had sold the contract of Foxx to the Chicago Cubs. At the age of 25, Lupien became the regular first baseman for the Red Sox.

“It’s Up to Him,” the Boston Herald captioned a picture of Lupien on the front page of the sports section on June 3, adding, “Ulysses Lupien, who has inherited the Red Sox first base job with the passing of Jimmy Foxx to the Chicago Cubs, looks pensively out on the Fenway Park sward.”

Lupien batted sixth in a star-studded Red Sox lineup that included Ted Williams and Bobby Doerr. After compiling just a .196 batting average for the Red Sox before Foxx was dealt to Chicago, Lupien had a tepid beginning as the starting first baseman. He inauspiciously went 0 for 3 and 0 for 4 in his first two post-Foxx starts at first base. Collecting two hits in his next game, though, Lupien went to produce a .290 average after Foxx had left the Red Sox, justifying the team’s confidence in him as the new Boston first baseman.

“You don’t succeed a player like Foxx. I only followed him at first base,” Lupien steadfastly said. Lupien absolutely despised the oft-repeated statement that he had replaced Foxx. “No one can replace Foxx,” Lupien lamented to author Golenbock. “And following him was a tremendous burden. I got caught in the same situation as Babe Dahlgren did in New York following Lou Gehrig. To follow a star is just impossible. It’s a disaster to follow a guy who can hit that ball over that left field fence.”

In 1943, on a team decimated by the loss of Williams and several other players to military service for World War II, Lupien hit a respectable .255 for a seventh-place Boston team after his customary slow start. His batting average was just .229 on Memorial Day before he perked up once the weather turned warmer.

Lupien expected to remain with the Red Sox for a third season in 1944, but a game-winning two-run double in an April 6 exhibition game in Wilmington, Delaware, against the Philadelphia Phillies changed his future. A week later, on April 14, just before Opening Day, the Red Sox sent Lupien to the Phillies on waivers.

“I was a line drive hitter who hit for average, an in-between hitter who got the bat on the ball. I didn’t have much power though,” Lupien said, hinting at the probable reason why the Red Sox let him go after only two seasons at first base in place of Foxx. Lupien had hit just seven home runs in two seasons with the Red Sox.

On the last-place 1944 Philadelphia team, Lupien continued his everyday playing habits and bat control ability by hitting .283 in 153 games. He even managed 18 stolen bases, finishing second in thefts among National League players. “Tony Lupien’s fine play at first base has been one of the features of the final days of the season,” The Sporting News commented on September 28. “The former Red Sox first sacker went on a batting rampage against the Giants and before he was halted by the Reds in the last game of four-game series, he made 17 hits in 34 times at bat, including three triples and two doubles.”

Before the 1945 season began, Lupien was inducted into the Navy, although he was supporting his wife, Natalie, and their two daughters, Judith and Diana (their third daughter, Carol, was born in 1947).

Instead of patrolling the infield at Shibe Park in Philadelphia, Lupien spent most of the 1945 baseball season patrolling the Sampson Naval Base in upstate New York. After he was discharged in September, Lupien rejoined the Phillies for the balance of the 1945 season, playing in 15 games and producing a .315 batting average for the last-place Phillies.

Although Lupien had played well that September, the Phillies in December purchased the contract of power-hitting first baseman Frank McCormick from the Cincinnati Reds. The move cast a shadow on Lupien’s role with the Phillies for the postwar 1946 season. That Lupien had no role on the club was affirmed in February 1946 when Philadelphia sold his contract to the Hollywood club of the Pacific Coast League. There was no doubt in Lupien’s mind that this demotion from the major leagues was a violation of the G.I. Bill of Rights, which promised returning servicemen their old jobs.

Lupien argued to Philadelphia general manager Herb Pennock that the club’s action violated the G.I. Bill, but he received no satisfaction from the baseball team. After his letter to Commissioner Happy Chandler was returned unopened, Lupien engaged in a media campaign to raise awareness of how returning baseball players were being treated unfairly by the major league owners.

“The law of the land gives Tony Lupien the absolute right to reinstatement as first baseman of the Phillies and not for fifteen days as the barons of the racket contend, but for one year,” Dave Egan, a fellow Harvard alumnus, wrote in the Boston Record in February 1946. “Baseball players who are veterans did not fight for the dubious privilege of selling apples on street corners and in common justice are entitled to the same rights as all other citizens. This is the first recorded instance in sport of a war veteran being denied his rights, but I am sorry to say that it is not the last, for by the first of May the woods will be filled with veterans, wondering what happened to them and their supposed rights.”

In early March, The Sporting News published a full page of coverage on the situation, under the headline “Lupien Case Threatening Test of Game’s Laws.”

“The G.I. Bill was designed to protect for at least one year the jobs of men who entered the service. Now that bill either applies to ballplayers or it doesn’t,” The Sporting News quoted Lupien as saying. “That’s what I am trying to find out, and if it means that I am the goat or the ball carrier, I am perfectly willing to assume that role. If the G.I. Bill does apply, then I may help many other veterans in the months to come by following through with my action.”

Lupien was startled to receive a contract offer from the Hollywood club that would pay him $8,000 a year, the amount he expected to be paid to play for the Phillies. This amount was far above what other PCL players would be paid.

“The major leagues were planning to circumvent the Veterans Act by paying the banished servicemen their prewar salaries, thereby meeting at least the provision that the former soldier received his previous salary,” Lee Lowenfish wrote in the 1980 book The Imperfect Diamond, which he co-authored with Lupien. “Tony Lupien was enough of a realist to realize his chances for a victory over the moguls were slim. Tony decided not to follow the path of litigation. When Tony arrived in Hollywood at the end of March, he resolved to play as well as he could in his effort to return to the majors.”

In his resolve to help other servicemen with their rights under the law, Lupien talked to Al Niemiec on a train ride just before the opening of the 1946 PCL season. Niemiec, who was playing for Seattle, was nervous about keeping his job on the team. After Seattle released Niemiec in April, he took his case to court. On June 21, Judge Lloyd Black ruled in favor of Niemiec, saying that the Veterans Act had been passed “to enable the serviceman to render the best he had for his country unworried by the specter of no payment during his first year after his return to civilian life.” Black also remarked that baseball owners were not “given the discretion to repeal an Act of Congress.”

The Niemiec decision put in motion the events that led to reforms in the standard player contract in August 1946 – minimum salary of $5,000, payment for spring training expenses, and creation of a pension plan – and eventually led to the formation of the Major League Players Association.

While Lupien had hated the idea of returning to the minor leagues, he grew to love playing in the PCL because of the favorable weather and the crowds that flocked to the games. His playing statistics reflected the positive energy about playing on the West Coast. After batting.295 for Hollywood in the 1946 season, he experienced his finest professional season in 1947. In 186 games for Hollywood in the lengthy PCL season, Lupien batted .341, with a league-leading 237 hits in 696 at bats and a surprising 21 home runs. His all-around play earned him the league’s most valuable player award. It also earned him a promotion back to the major leagues, but to the lowly Chicago White Sox, the team Hollywood was then affiliated with.

“I hated to leave the Pacific Coast League for the White Sox,” recalled Lupien, who had grown to appreciate what the temperate climate did for his play on the field. “It was too cold in Chicago.”

Lupien continued his yeoman playing habits with the 1948 White Sox, playing in 154 games for the last-place team in the American League. But the White Sox, eyeing Lupien’s .246 batting average and only six home runs for a last-place entry, sought a new first baseman and shipped Lupien to Detroit in January 1949. When Lupien didn’t make the Tigers in spring training (although he did make it onto a Bowman baseball card), he was assigned to the team’s Triple A affiliate in Toledo. After a frustrating season in Toledo, with no immediate prospect of returning to the major leagues, Lupien asked to be put on the voluntary retired list and officially left baseball at the age of 32.

Although Lupien regretted his decision to prematurely retire from playing baseball, in the long run the decision helped to shape his post-baseball career. Because he had to sit out at least one year before he could return to Organized Baseball, in 1950 Lupien became player-manager of the semi-pro Claremont, New Hampshire, team. With some experience as a manager under his belt, Lupien persuaded Detroit to hire him in 1951 as player-manager for the club’s Class D farm club in Jamestown, New York, in the PONY League.

In his first year as a manager, Lupien piloted the Falcons to a tie for first place, but then lost the playoff for the top spot to Olean, 6-1. Disheartened, Jamestown quickly bowed out of the playoffs in the first round. In 1952, Lupien’s team finished in second place again, two games from the top. This time, however, Jamestown won the playoff championship by sweeping both playoff series by four games to none. Lupien was also the league’s all-star first baseman on the strength of his .352 batting average.

When his managerial feats at Jamestown weren’t rewarded with a promotion to a higher-level farm club in the Detroit system, Lupien briefly managed the independent Corning team in the PONY league. Midway through the season, though, Lupien shucked the low pay and uncertainty of minor league managing and left professional baseball for good, after the death of his wife, Natalie, in May 1953.

In 1957, Lupien accepted an offer for a position that was more suited to his love for baseball and didn’t involve the politics of the professional level. He was hired to coach the baseball team at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, taking over a program that had undergone seven consecutive losing seasons. In Lupien’s first year at Dartmouth, he turned around the program with a team that produced an 11-7 record.

Lupien went on to coach Dartmouth for twenty-one years, compiling a 313-305-3 record. Lupien and his second wife, Mildred, along with their two daughters, Elizabeth and Suzanne, established a home in Norwich, Vermont, across the Connecticut River from the Dartmouth campus.

The pinnacle of Lupien’s college coaching career was the 1970 season, when Dartmouth qualified for its first-ever appearance in the College World Series. After a slow 3-8 start that season, Dartmouth rattled off twenty straight victories to earn a berth in college baseball’s top tournament. The winning streak was capped with a 12-3 victory over the University of Connecticut on June 4 for the NCAA District One championship.

“These guys are something else,” Lupien told the Manchester (New Hampshire) Union Leader after his players doused him with champagne in a victory celebration. “They’re such an unselfish team. Everyone has done his part. I couldn’t be more pleased.” Dartmouth defeated Iowa State in the first round of the College World Series for a twenty-first consecutive win, but then bowed out with losses to Florida State and the University of Southern California..

At the heart of Lupien’s pitching staff in 1970 were senior Chuck Seelbach and sophomore Pete Broberg. Both went on to pitch in the major leagues. Broberg was a first round draft choice of the Washington Senators in 1971, after his junior year at Dartmouth. (Broberg was one of the few players since the institution of the amateur draft in 1965 to advance straight to the major leagues without first playing in the minors.) Seelbach pitched in 75 games over four seasons (1971 through 1974) for the Detroit Tigers.

What his Dartmouth players remember most about Lupien was not only his baseball knowledge but also his refusal to coddle college players.

“Tony was what the Marines call the ‘old breed.’ Teach skills and competence and a love of the game – and to hell with people’s feelings,” says Barry Machado, captain of the 1966 Dartmouth baseball team and now a history professor at Washington & Lee University. “When the sensitivity-and-self-esteem crowd gained the upper hand in American culture, Tony was at a loss. He never did make his peace with the athlete more interested in styling, showcasing, and showboating. For Tony, baseball was 100 percent a team sport. Tony was a great teacher of the game. Tony had mastered his subject and there was much to learn from the master.”

“I did not appreciate Tony then as much as I did later and I do now,” says Broberg, now a lawyer. “He truly loved his players, but it was tough love. He demanded 105 percent and you did not play unless you gave it. There were no prima donnas.” Lupien’s hands-off attitude helped Broberg. “I do not believe Tony directly helped my pitching career,” Broberg says. “But by not trying to change anything, he did not screw up my mechanics like a few of the big league coaches did.”

Lupien loved baseball, but he was quite outspoken about his disdain for the moneyed aspects of today’s major league offering.

“It seems like today, because of the emphasis on individual statistics and greed on the part of everyone, players and owners alike, that a fellow is more interested in his record than he is in how the team does,” Lupien said in a 1997 remembrance about the “team” aspect of baseball. “So if he has to face a tough lefthander on a certain day, or he doesn’t feel well, he has to get out of the lineup and rest for a day or two.”

“We played day in, day out, drunk or sober, sick or well,” Lupien emphasized. “You’re going to have days when you face pitchers that you’re not going to hit, but you do something else to help the ball club. Maybe you’ll get a base on balls; maybe you’ll steal a base; maybe you’ll go from first to third on a play that is going to change the ballgame. Maybe you will make a great defensive play and help us. I think this is a great lesson for a young hitter to learn.”

There was never any doubt where Lupien stood on an issue. With an independent spirit, he spoke his mind about what he believed to be the right thing. Baseball was a team game – no discussion. Could he have tried to hit more home runs as a player to extend his major league career? Sure, but that would have violated the principle of baseball being a team game.

Tony Lupien was a true ballplayer to the core. Baseball lost part of its soul when Lupien died on July 9, 2004 at his home in Norwich, Vermont. He was buried there in Hillside Cemetery.

Sources

Baumgartner, Stan, “Lupien Case Threatening Test of Game’s Laws,” The Sporting News, March 7, 1946.

Bevis, Charlie, “Chelmsford’s Gift to Pro Baseball,” Chelmsford Independent, August 1, 1991.

Bevis, Charlie, “Tony Lupien, the Chelmsford Kid Who Replaced a Baseball Legend,” Lowell Sun, May 31, 1992.

Boston Herald, 1940-1944

Chelmsford Newsweekly, “Townspeople To Pay Tribute to Tony Lupien Sunday,” September 24, 1942.

Dartmouth College Athletic Department

Egan, Dave, “Swings on Baseball for Lupien Brushoff,” Boston Record, February 25, 1946.

Golenbock, Peter, Fenway: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1992.

Harvard University Archives, Lupien biographical file

Lowenfish, Lee and Tony Lupien, The Imperfect Diamond, Stein and Day, 1980.

Lupien, Tony, “Personal Memories of the ’41 Colonels,” A Celebration of Louisville Baseball in the Major and Minor Leagues, SABR, 1997.

Manchester Union Leader, 1970.

The Sporting News, 1942-1946.

Wood, Bruce, “Colleagues Remember an Ivy League Original,” Valley News, July 11, 2004.

Full Name

Ulysses John Lupien

Born

April 23, 1917 at Chelmsford, MA (USA)

Died

July 9, 2004 at Norwich, VT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.