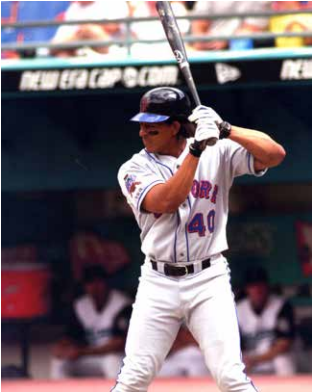

Tony Tarasco

“In right field, Tarasco going back to the track, to the wall … and what happens here? He contends that a fan reaches up and touches it, but Richie Garcia says, ‘No!’ it’s a home run,” Bob Costas shouted through the broadcast microphone over a raucous Yankee Stadium crowd.

“In right field, Tarasco going back to the track, to the wall … and what happens here? He contends that a fan reaches up and touches it, but Richie Garcia says, ‘No!’ it’s a home run,” Bob Costas shouted through the broadcast microphone over a raucous Yankee Stadium crowd.

The moment: Game One of the 1996 American League Championship Series, bottom of the eighth inning, Yankees trailing their AL East rivals, the Baltimore Orioles, 4-3, with rookie phenom shortstop Derek Jeter at the plate.

Because of this one moment, Jeter and journeyman outfielder Tony Tarasco will always be linked in baseball history. The reality, though, is that Jeter would enjoy a long career with many more postseason triumphs, more than all but a handful of players who have ever lived. Tarasco had only two postseason at-bats, and struck out in both of them, once for the Braves in 1993 and once for the Orioles in 1996.

The real link, however, is between Tarasco and 12-year-old Jeffrey Maier, the boy who reached over the right-field wall at Yankee Stadium on that memorable October evening to take away what likely would have been a key second out for Orioles reliever Armando Benitez. Benitez, it should be noted, sprinted out to the right-field fence as fast as he could to get in his two cents with Garcia, the right-field umpire.

This was the beginning of another Yankees dynasty, and of Jeter taking the reigns as “Mr. October” from former Yankees great Reggie Jackson. It is fun to speculate on how history may have turned out differently had Maier kept his glove to himself and allowed Tarasco to catch the ball.

Whether Tarasco would have caught the ball is another question. It took multiple replays for the three-man NBC crew of Costas, Joe Morgan, and Bob Uecker to recognize that the ball was clearly in the field of play when Maier fished it out of the air. It took a few more replays and arguments for the three to agree Tarasco, though he did not leap as high as he could to attempt to make a catch, would have likely caught the ball if not for the uncalled fan interference.

The result was 15 minutes of fame for Maier, a tie ballgame the Yankees would go on to win, and the pinnacle moment of Tarasco’s eight-year big-league career. To say, though, that it was the only notable moment of Tarasco’s career, and especially of his life, would be to sell Tarasco short as a player and man.

Of all the men who have played major-league baseball, few have had as compelling a story as Tarasco’s.

After being born on December 9, 1970, in New York City, and raised for the first nine years of his life in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, Tony spent the rest of his childhood on the other coast in Santa Monica, California, not far from South Central Los Angeles. He was an older cousin to 17-year major-league shortstop Jimmy Rollins.

Tony’s father, Giacinto, moved the family to the opposite coast because Tony was often getting into trouble. Being mere miles from South Central and Tony becoming a part of the world-famous Santa Monica Graveyard Crips was not exactly the answer to keeping his son out of trouble.

Tony became friends with members of the Crips and joined their gang. Tarasco once reminisced about his time in Santa Monica, “A lot of what I was doing in the early part of the ’80s was no different from what you would see in West Side Story, a lot of street gangs and fighting and stuff. As I got into high school, it started to get a little rougher. It was a lot more violent. There was more shooting and stuff.”1

”I was never a soldier in the gang,” Tarasco told Jack Curry of the New York Times. ”Soldiers do everything. I was into the hustle so I could make a few bucks and dress nice for the girls. I was never into the raw dog, dirty stuff.” Tarasco said that six of his friends had been killed on the streets — he bore a tattoo honoring one of them — and, Curry added, “he once missed a drive-by shooting at a fast-food restaurant because he was in the bathroom.”2

Yet Tarasco was mostly able to avoid the lure of the streets. He reported engaging in some of the activities of his gang, but said he only took part because he wanted to have nice clothes in order to impress girls at school. For him, the gang was the group of friends he spent time with when he was not busy playing ball.

And for Tarasco they proved to be not what they were often portrayed as: violent hotheads. They understood he had unusual ability. His bat, his legs, his arm; all were gifts he received. He did not have the option to waste them. For this reason, his friends in the gang pushed him away from the gang life. They knew he had the chance to do what every kid who comes from such an environment dreams of doing. He had the chance to get out and make something of his life.

To that end, Tarasco did not merely survive the streets. He got out. And he was able to do so because he was one of the best baseball players to ever play at Santa Monica High School, the academy better known for producing acting talents like Emilio Estevez and brother Charlie Sheen, Rob Lowe, and Sean Penn.

The most notable athlete from Santa Monica High of recent times is Baron Davis, a point guard who starred at UCLA for two years before enjoying a long, star-studded career in the NBA with the Charlotte and New Orleans Hornets, Golden State Warriors, and Los Angeles Clippers.

Not surprisingly, Davis, before, during, and after his basketball career, pursued acting, directing, and producing, in addition to music endeavors. It is simply what kids from Santa Monica do.

Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that Tarasco, too, tried his hand at acting, though his roles were far from the starring variety. They barely even qualified as cameo roles. Like Davis, Tarasco first pursued entertainment opportunities prior to reaching stardom as an athlete. And like Davis, he continued after his playing career was completed.

His first role came in 1991, when Tarasco was toiling through the minor leagues in the Atlanta Braves farm system. His role: “baseball player,” in the 1991 film, Talent for the Game. When the film was released, Tarasco was a 21-year-old outfielder on the rise in the Braves organization, which itself was on the rise.

In the film Tarasco, however, was a member of the Kansas City Royals, a bit ironic given that he would wear a Royals uniform in the twilight of his playing career, though never in a regular-season contest. Tarasco was one of a number of big leaguers past, present, and future in the cast. Among them were Bobby Tolan, Derrel Thomas, Lenny Randle, Rudy Law, Phil Lombardi, and Steve Ontiveros. The reality is that Tarasco’s role in the film was about as memorable as the bulk of his playing career in the big leagues, other than the episode already highlighted in the 1996 ALCS.

But that, too, is probably short-changing Tarasco’s accomplishments as major-league baseball player. For the career, the numbers do not appear terribly impressive: .240 batting average, 34 home runs, 118 runs batted in, and 151 runs scored.

For some players, that is a season. Then again, Tarasco was not a power-hitting slugger. His game was speed, especially in the outfield, which enabled him to become one of the better defensive outfielders of his generation.

In eight seasons, Tarasco made just seven errors defensively. The seven errors covered 522 chances as a defender. That is good for a career .987 fielding percentage. Using more advanced methods of evaluating defensive performance, Tarasco routinely saved his team runs. By 1994, his second year in the big leagues, Tarasco was good for negative runs as a defender.

By prorating his totals to a full 162-game season, Tarasco saved his Braves 15 runs as a left fielder. By the time he got to the Orioles in 1996, he was good for 30 saved runs over the course of a season, now as a right fielder. His best defensive season, by this measure, came in 1997, when he was good for 36 runs saved over a full season, while playing left field.3

Much of these numbers, which are still in their relative infancy in baseball parlance, came about because of Tarasco’s incredible speed and instincts. He would routinely catch a ball that off the bat seemed destined to fall in for a hit. It took baserunners time to learn Tarasco caught almost everything.

In 1995 alone, Tarasco turned three double plays as an outfielder, an unusually high number for someone who played in only 126 games, 114 of which he began in the starting lineup. Tarasco, however, was not only a defensive wizard in that first full season after major-league baseball’s last major player strike. Despite playing in only 126 games, his three double plays were one less than outfielders Bernard Gilkey and Sammy Sosa, the league leaders in the category, had.

In his only season with the Montreal Expos, 1995, Tarasco was a dynamic playmaker. He had by far his most plate appearances in a season, 495. Tarasco hit .249 but was on base at a .329 clip thanks to 51 walks, 12 of which were intentional. Those 12 free passes show opponents’ respect for the 25-year-old outfielder. In his lone season north of the border, he also hit a career-high 14 home runs with 40 RBIs.

The speed that made him such a slick defender was ever present on the basepaths as well. The 15th-round draft pick out of high school stole 24 bases in 27 attempts. He never stole more than five in a season again. With the Expos he set a personal high with 64 runs scored. His next best season was 1997, when he scored 26 times.

The 6-foot, 185-pound outfielder was one of three Braves traded in an April 6, 1995, deal when he went from Atlanta to Montreal. The deal included outfielder Marquis Grissom. Tarasco was probably the least notable name involved in the deal.

Just one year later, after a solid 1995 campaign, Tarasco was dealt in a look-to-the-future cost-cutting move for Baltimore’s Sherman Obando, like him an outfielder and pinch-hitter.

The 1996 season, his first foray into the American League, was a less-than-smooth ordeal for Tarasco. He played in only 31 games for the Orioles and had just 84 at-bats. He hit .238 with a .297 on-base percentage and slugged only .310. After May 11 he was shipped to the minors.

His minor-league campaign in that season was only minimally better: 41 games for three different teams, 146 at-bats, .260 batting average, .360 on-base percentage, and a .390 slugging percentage.4 The 1996 season was a struggle through and through for Tarasco, making it improbable that the moment he is most known for would even occur. Then again, his defense alone was deemed worth a postseason roster spot.

Tarasco’s postseason career was not one to write home about. He had one at-bat in Game One of the 1993 NLCS, in the top of the 10th in a tie game against the Phillies. There were runners on second and third with two outs, but Mitch Williams struck him out. The Phillies won in the bottom of the 10th. His only other at-bat was for the Orioles in 1996, and he struck out then as well. He was used defensively in one other game in each series. It may be less of a surprise that Tarasco would end up as a glorified extra in multiple film projects. Born to a Sicilian father and a mother from Trinidad, Anthony Giacinto Tarasco, especially in his playing days, had the kind of looks that would attract Hollywood. The film Talent for the Game was not the only time he struck a pose for the camera.

He also played Pablo in the 2005 feature, The Helix … Loaded. As was true before, Tarasco’s role was not a large one. This time around Tarasco should feel fortunate he was not a featured star. The 97-minute action comedy barely earned two stars on the IMDB movie page.5 Another movie critic site, rottentomatoes.com, gave it a 14 percent audience score.6 The film, which featured Scott Levy and Vanilla Ice, was an epic flop.

It did little to bring Tarasco additional notoriety, following his last few mostly forgettable years in the big leagues. His most memorable moment in the big leagues (in a negative way) was followed by his next busiest offensive season, once again with the Orioles.

In late March 1998, Tarasco was selected off waivers by the Cincinnati Reds; he played just 15 games with Cincinnati. He spent most of the season in Triple-A Indianapolis, where he hit .313 in 90 games. A year later, he signed as a free agent with the New York Yankees, but played just 14 games for the pinstripers. He hit .295 in 95 games for their Triple-A Columbus Clippers. The calendar passed by Y2K, plus a couple more years, before Tarasco would see time in the big leagues again. In 2000, he had played in Japan’s Central League for the Hanshin Tigers. He signed with the New York Mets for 2001, and spent most of the time in Triple A again, with the International League’s Norfolk Tides. He hit. 292, with a .371 on-base percentage.

While Tarasco’s playing career didn’t quite turn out as hoped for, and his acting career was essentially a big flop, it cannot be said his career was uneventful or even undistinguished.

To speak to the former, Tarasco was involved in three other controversial New York City baseball stories during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But during Tarasco’s brief stint as a Yankee in 1999, the reserve outfielder caused a stir by walking up to the plate to a profanity-laced “Tommy’s Theme” from the well-known New York City hip-hop trio The Lox. Tarasco pleaded innocence, despite his penchant for living life on the edge, at least in comparison to the average Yankee, claiming he had asked for the edited version to be played as his walk-up song. Whether true or not, the Yankees fired the scoreboard operator in charge of playing the song. Once again Tarasco was able to get out of responsibility for a major glitch at Yankee Stadium involving him.7

The last of the three moments was the most egregious and ultimately one Tarasco couldn’t escape blame over. After a 6-3 Mets home loss to the division rival Atlanta Braves on June 26, 2002, Tarasco and relief pitcher Mark Corey smoked a joint of marijuana somewhere just outside Shea Stadium.8

The 27-year-old Corey burst into convulsions. Once it was learned that he was okay, and that personal issues in his life were to blame for his taking part in this illegal act, eyes began to shift toward Tarasco. What role did he play in this episode beyond taking part?

Given his youthful inclusion in an LA gang, and a continued “rough” exterior, Tarasco seemed to be a possible perpetrator of wrongdoing against his teammate. Media members wondered whether Tarasco had laced the marijuana with something stronger, thereby making it more potent and more likely to throw a well-conditioned athlete like Corey into the multiple episodes.9

Earlier in that year Tarasco was investigated by Major League Baseball for a nightclub incident involving a woman who began experiencing seizures after sipping a drink.10 Thus there was precedent for asking the question of whether Tarasco was a serial drug lacer. In neither case was he found guilty, and he went on to have a better career as a coach than as a player. But no matter what else happened in his baseball career, it would always be the evening of October 9, 1996, he was best known for.

As a coach Tarasco worked his way through the Washington Nationals’ minor-league system, helping to develop young players most specifically in the two areas in which he particularly excelled as a pro: baserunning and his work in the outfield. He played a large role in overseeing the development of future superstar outfielder Bryce Harper, whom the organization took with the number-1 overall pick in 2010 as a high-school catcher from Las Vegas. By his age 24 season Harper became a better-than-average defensive outfielder, in addition to being one of the most dangerous hitters in the game, and an aggressive and effective baserunner.

The experienced coach was integral to the success of developing the Nationals’ deep bench as well, and the development of lesser known prospects into big-time contributors at the big-league level. Case in point: Michael Taylor, a shortstop with little upward trajectory in the organization had he remained at that position. But then the front office decided to make him an outfielder and turn him over to Tarasco.

“I remember the first day he went out to play. We worked out for a couple days, took him through his foundation and just talked to him about a few things,” Tarasco said. “He went gap to gap, from one side of the gap to the other side of the gap on the wall and made a play. At that moment, you just knew that (vice president of player development) Doug Harris and (general manager) Mike Rizzo had made the right decision in moving him over to center field.”11

Taylor went on to make a splash at the big-league level, right about the same time Tarasco found himself wearing a Nationals uniform and manning the first-base coaching box under manager Matt Williams. He coached first base for the Nationals from 2013 through 2015. Unfortunately for all involved, including Tarasco, the Nationals underachieved with Williams at the helm, costing not only him but his entire coaching their jobs.12

Tarasco quickly landed another job, this time in the San Diego Padres organization as the minor-league roving outfield and baserunning coordinator — essentially his job in the Nationals’ organization prior to his promotion to the major-league club.13

Would Tarasco have had so many opportunities in baseball or outside of it if not for his role that fateful October evening in 1996? It’s almost impossible to say for sure. But it is clear that he and Jeffrey Maier gained notoriety they may not have otherwise.

The two would meet again five years later at a youth baseball camp in Demarest, New Jersey. Maier, as a 17-year-old, was a coach. Tarasco was brought in as a guest speaker. As told by a camper who was there, the two shook hands and talked. As Tarasco addressed the young baseball hopefuls, one asked if there was anyone there he would like to fight?14

By all accounts, Tarasco downplayed the question and did not address the elephant in the room. His critics might point to that moment as one of his most mature as a big leaguer. Others might say it’s just how you would expect him to handle it. Either way, their meeting was a reminder that both gained their notoriety primarily from one very memorable moment. Tarasco’s story, though, is about much more than having a home run taken from his grasp.

Instead, it’s about a kid who overcame great odds to carve out a long career in baseball.

Last revised: March 1, 2018

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Norm Wood, “A Touch of Tarasco Sauce,” articles.dailypress.com/2001-07-05/sports/0107050009_1_santa-monica-high-tony-tarasco-rich-kids, July 5, 2001, accessed March 10, 2017.

2 Jack Curry, “Tarasco’s Agenda: Gang Life to Yanks,” New York Times, May 16, 1999.

3 baseball-reference.com/players/t/tarasto01-field.shtml, accessed June 16, 2017.

4 m.mlb.com/player/123094/tony-tarasco?year=2002&stats=career-r-hitting-minors, accessed June 16, 2017.

5 imdb.com/title/tt0401462/, accessed June 16, 2017.

6 rottentomatoes.com/m/the_helix_loaded, accessed June 16, 2017.

7 Peter Botte, “A.J. Burnett and Curtis Granderson Get Changeup on Yankees Scoreboard’s Closed-Captioning,” nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/yankees/burnett-curtis-granderson-changeup-yankees-stadium-scoreboard-closed-captioning-article-1.166812. April 15, 2010, accessed September 22, 2017.

8 “Two Mets players caught smoking marijuana,” foxnews.com/story/2002/06/29/two-met-players-caught-smoking-marijuana.html, September 22, 2017.

9 Michael Morrissey, “Drug Talk Sends Mets Into Shell,” nypost.com/2002/06/29/drug-talk-sends-mets-into-shell/, October 9, 2017.

10 “Two Mets Players Caught Smoking Marijuana,” foxnews.com/story/2002/06/29/two-met-players-caught-smoking-marijuana.html, September 22, 2017.

11 Bryan Kerr, “Tony Tarasco on Outfielder Michael Taylor: ‘The kid’s a specimen,’” masnsports.com/byron-kerr/2014/07/tony-tarasco-on-outfielder-michael-taylor-the-kids-a-specimen.html. July 3, 2014, accessed September 30, 2016.

12 Chelsea Janes, “For Some Nationals Coaches, End Evokes Memories of the Beginning,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/nationals/for-some-fired-nationals-coaches-end-evokes-memories-of-the-beginning/2015/10/05/57587f42-6ba0-11e5-aa5b-f78a98956699_story.html?utm_term=.12145e81834b, October 5, 2015, accessed September 22, 2017.

13 Dennis Lin, “Padres Announce Minor League Staffs for 2016,” sandiegouniontribune.com/sports/padres/sdut-padres-announce-minor-league-staffs-for-2016-2016jan14-story.html, January 14, 2016, accessed September 22, 2016.

14 Contillo, “The Second Time They Met, Jeffrey Maier Didn’t Dare Mess With Tony Tarasco,” deadspin.com/5922164/the-second-time-they-met-jeffrey-maier-didnt-dare-mess-with-tony-tarasco, July 2, 2012, accessed September 22, 2017.

Full Name

Anthony Giacinto Tarasco

Born

December 9, 1970 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.