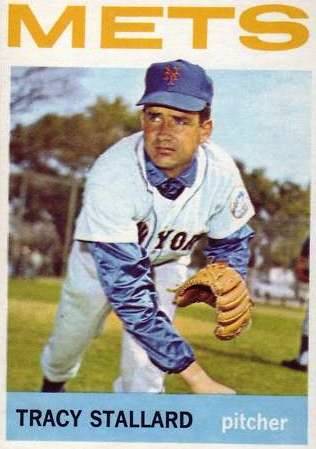

Tracy Stallard

With one pitch, Tracy Stallard guaranteed himself a place in baseball history, when, on October 1, 1961, he gave up the home run that allowed Roger Maris to pass Babe Ruth and lay claim to one of baseball’s most cherished records, the single-season home run standard. Ironically, Stallard’s 1-0 defeat represented one of the best games the young right-hander pitched that year (He called it “probably the best game I ever pitched.”); he held the potent Yankees offense to five hits in seven innings and struck out five with Maris’s solo shot the only run the powerful Bronx Bombers could muster. No less ironic is the fact that a year before, on October 1, 1960, in his last matchup against Maris, Stallard, in a relief stint, had struck out the soon-to-be-named American League Most Valuable Player, when the Yankees, tuning up for the World Series, had defeated the Red Sox 3-1. But in the end none of that mattered as Stallard’s 14-year professional career, seven seasons of which were in the major leagues, would be forever defined by a single pitch.

With one pitch, Tracy Stallard guaranteed himself a place in baseball history, when, on October 1, 1961, he gave up the home run that allowed Roger Maris to pass Babe Ruth and lay claim to one of baseball’s most cherished records, the single-season home run standard. Ironically, Stallard’s 1-0 defeat represented one of the best games the young right-hander pitched that year (He called it “probably the best game I ever pitched.”); he held the potent Yankees offense to five hits in seven innings and struck out five with Maris’s solo shot the only run the powerful Bronx Bombers could muster. No less ironic is the fact that a year before, on October 1, 1960, in his last matchup against Maris, Stallard, in a relief stint, had struck out the soon-to-be-named American League Most Valuable Player, when the Yankees, tuning up for the World Series, had defeated the Red Sox 3-1. But in the end none of that mattered as Stallard’s 14-year professional career, seven seasons of which were in the major leagues, would be forever defined by a single pitch.

Tracy Stallard was born on August 31, 1937, in Coeburn, Virginia. A local legend, the 6-foot-5, hard-throwing pitcher was unbeaten in four years of baseball at Coeburn High School, capping his career with an 8-0 senior year that included two no-hitters. It was an effort that would earn him induction into the Virginia High School League Hall of Fame in 2005. It also earned the attention of major-league scouts and Stallard was signed by the Boston Red Sox in 1956. Assigned to the Lafayette Red Sox in the Class D Midwest League, the lanky 18-year-old compiled a 5-8 record with an earned-run average of 4.50 in 17 games and just over 100 innings. A second year with Lafayette yielded similar results as the tall right-hander started 16 games en route to a 7-12 record. Things started to come together the following year when Stallard, assigned to Raleigh in the Class B Carolina League, lowered his ERA to 3.09 while winning nine games and losing six. He started 1959 with the Allentown Red Sox in the Class A Eastern League, where he went 9-4 with a 1.68 ERA in 13 starts before earning a promotion to the Minneapolis Millers in the Triple-A American Association. There his record was only 2-5, but his ERA was 2.25. The following year Stallard experienced a similar arrangement. He spent time back in Allentown, where he went 4-5 with an ERA of 4.82, and in Minneapolis he had a 7-11 record and an ERA of 3.51, pitching all but four of his 34 games in relief.

Finally, after five seasons toiling in the minors, Stallard spent the whole of 1961 with the Red Sox. He appeared in 43 games, starting 14 and finishing with a record of 2-7 for the sixth-place Red Sox. He pitched 132 2/3 innings with an ERA of 4.88, but the whole season was overshadowed by his being the victim of Roger Maris’s record-breaking 61st home run in the fourth inning of the 1-0 season finale. It was a bittersweet end to Stallard’s season and he spent most of 1962 back in the minors. He did make one brief appearance with the Red Sox, recording a single shutout inning, but the rest of the year was spent toiling for the team’s Pacific Coast League Triple-A affiliate, the Seattle Rainiers. There he finished 7-6, with an ERA of 3.49 in 38 games. Stallard started 13 games and counted one shutout among his three complete games.

He went to the New York Mets after the 1962 season in a multiplayer deal that had Stallard and infielders Al Moran and Pumpsie Green being swapped for infielder-outfielder Felix Mantilla. With the Mets Stallard was a regular member of the rotation, but his record reflected the Amazin’ Mets of the era. Indeed, after compiling a 6-17 record with an ERA of 4.71 in 1963, he lowered his ERA by almost a full run in1964, only to have the Mets offense leave him stranded as he suffered 20 losses to lead the league in that unenviable category. Despite that, his ten wins included two shutouts among 11 complete games. Unhappily for Stallard, the 1964 season also saw him again on the wrong end of history as he was the losing pitcher in both the longest game in major-league baseball history up to that point, a 7 hour 23 minute marathon with the San Francisco Giants in May, and Jim Bunning’s Father’s Day perfect game against the Mets the next month.

At the end of the 1964 season Stallard was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. Although the Cards were coming off a World Series victory over the Yankees, Stallard earned himself a regular spot in a rotation headed by future Hall of Famer Bob Gibson, and had the best season of his career in 1965. Starting 26 games, he compiled a record of 11-8 with a career low ERA of 3.38, second best on the team behind Gibson. He threw one shutout and had four complete games while pitching just under 200 innings. Despite his stellar 1965 effort, Stallard split the 1966 season between the Cardinals and the Texas League Tulsa Oilers. In what proved to be his final major-league stint, Stallard had a 1-5 record and a 5.68 ERA in 20 games for the sixth-place Cardinals, while his efforts in Tulsa resulted in a 3-3 record and a 5.58 ERA in eight starts.

The time in the minors in 1966 did not bode well for Stallard’s baseball future, and he did not make the Cardinals’ 1967 major-league roster, a squad that included Roger Maris, who had been traded by the Yankees and would ultimately finish his major-league career as an important contributor on the 1967 and 1968 Cardinals teams that won two National League flags and the 1967 World Series. In contrast, still seeking to keep his career alive, Stallard pitched in the minors for two different teams in 1967. A stint with the Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs in the Double-A Texas League resulted in a 2-7 record and an ERA of 4.35 in 12 games and 60 innings, and a chance to return to Triple-A Tulsa, a Chicago Cubs affiliate, where he started 15 games en route to a 4-7 mark and an ERA of 4.50. Stallard dropped out of professional baseball for a year before making a final comeback attempt in 1969. Pitching for the High Point-Thomasville Royals in the Class A Carolina League, Stallard appeared in 25 games, pitching 57 innings, all in relief, as he compiled a record of 3-4 with an ERA of 2.68. However, it was not enough to prolong his career, and at 31 he retired from professional baseball and returned to Virginia.

Stallard’s career numbers reflected his doggedness, if not his talent. In the nine seasons in which he appeared in the minor leagues, he compiled a record of 62-77 while starting just over half of the 256 games he appeared in. His minor-league ERA was 3.68 in just over 1,000 innings pitched. Meanwhile, in parts of seven major-league seasons, he won 30 games while losing 57. There too, he started a little more than half of his 183 games and he achieved a career ERA of 4.17 while pitching 764 2/3 innings.

And yet for all of that, Stallard would be forever remembered as the man who gave up Roger Maris’s 61st home run. It was an infamy with which he came to terms—at least initially. In the immediate aftermath of the event, Stallard commented that he didn’t feel bad about giving up the record-breaker, pointing out that lots of other guys had given up home runs to Maris. Beyond that, at least in the early years of his retirement, Stallard seemed to have fun with his notoriety, commenting that he was glad he had given up the historic blast because given the rest of his career he was not the kind of player who would have been remembered were it not for the Maris home run. Too, while he turned his energies to the business world upon his retirement from baseball, Stallard kept in touch with the game, playing in occasional old-timers contests, and he even put in a couple of appearances at the Roger Maris Golf Tournament in Fargo, North Dakota, winning the charity fundraiser in 1990. However, by 1998, decades removed from his brush with fame and fully invested in overseeing his coal business in Virginia, Stallard showed no interest in being a part of the circus that surrounded the home-run duel of Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, a drama that not only served to introduce Maris to a new generation of fans but also brought Stallard a new round of unwanted attention. Reflective of his enduring status as a local legend, in 1997, a new baseball field at Stallard’s alma mater, Coeburn High School, was named in his honor. And yet, true to his continuing desire to keep a low profile and go on with his life, Stallard was not in attendance at the first game at the newly dedicated field.

He died at the age of 80 on December 7, 2017.

Sources

Hayes, Tim. “Local Legends: Coeburn High School’s Tracy Stallard.” TriCities.com: http://www2.tricities.com/sports/2008/sep/29/local_legends_coeburn_high_schools_tracy_ stallard-ar-250878

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, editors. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, second edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc. 1997.

Rosenberg, Michael. “Tracy Stallard Prefers To Be Left out of Baseball History.” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1998.

Shaughnessy, Dan. “Tracy Stallard: He Yielded No. 61 to Roger Maris.” Baseball Digest, January 1992.

Smith, Ron. 61*. St. Louis: Sporting News. 2001.

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.baseballlibrary.com

www.centerfieldmaz.com

Full Name

Evan Tracy Stallard

Born

August 31, 1937 at Coeburn, VA (USA)

Died

December 7, 2017 at , ()

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.