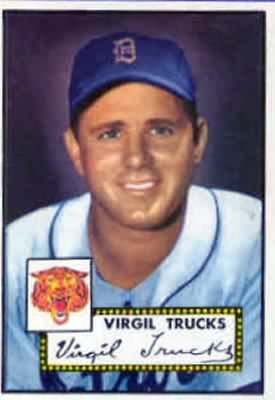

Virgil Trucks

The last-place Detroit Tigers went to New York to meet the reigning World Series champion Yankees in August 1952. After Detroit lost the first game of the series, Virgil Trucks started Game Two. The veteran right-hander came in with a 4-15 record, but he had pitched a no-hitter and a one-hitter for two of his victories. On August 25 Trucks had his fastball humming and threw his second no-hitter of the season; however, the game was marked by controversy involving an error, an official scorer, and even a phone call to the fielder involved. In an interview with the author, Virgil Trucks recalled this exceptional game:

The last-place Detroit Tigers went to New York to meet the reigning World Series champion Yankees in August 1952. After Detroit lost the first game of the series, Virgil Trucks started Game Two. The veteran right-hander came in with a 4-15 record, but he had pitched a no-hitter and a one-hitter for two of his victories. On August 25 Trucks had his fastball humming and threw his second no-hitter of the season; however, the game was marked by controversy involving an error, an official scorer, and even a phone call to the fielder involved. In an interview with the author, Virgil Trucks recalled this exceptional game:

“In the [third] inning, Phil Rizzuto hit a groundball to Johnny Pesky. We thought he’d thrown him out at first, but the umpire called him safe. When I walked off the field, on the scoreboard you could see there was an error. When I went back onto the field to start the third inning, there had been a hit put up. … The scorer that day was John Drebinger [of the New York Times], and the sportswriters were getting on him for changing it from an error to a hit. He called down to the bench and talked to Johnny Pesky; Pesky said that it was nothing but an error. The ball was not stuck in his glove, he said; he just could not get a grip on it. Drebinger accepted his word. When I went out in the eighth inning, they announced over the PA system what [Drebinger had] done and it had been corrected as an error. They put an error back on the board and it was still a no-hitter.”1

Right-hander Virgil “Fire” Trucks set down the Yankees in order in the eighth and ninth to join Johnny Vander Meer and Allie Reynolds as the only pitchers to throw two no-hitters in the same season. (Nolan Ryan joined them in 1973, and in 2010 Roy Halladay tossed a no-hitter in the regular season and the postseason.) With 19 losses and just five victories for the year, Trucks provided some of the few highlights for a Tigers team that finished the season in eighth place at 50-104, the first time in franchise history that the Tigers lost 100 games or finished last in the AL.2

Virgil Oliver Trucks was born on April 26, 1917, to Lula Belle and Oliver Trucks in Birmingham, Alabama. Raised at home by his mother and by Aunt Fannie, an African American nanny, Virgil was the fourth of 13 children. He had eight brothers and four sisters.3 Virgil’s first encounters with baseball were as a toddler with his father. Oliver operated a company store for the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company in Birmingham and played for the company baseball team in a local sandlot league. Virgil recalled that his father, an accomplished pitcher, was offered a minor-league contract by the Nashville Vols of the Southern Association and “probably could have made the major leagues, but with four kids at the time, he couldn’t leave home.” He snuck into his father’s games and also into Rickwood Field, where the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association and the Black Barons of the Negro Leagues played. By the age of 10, Virgil was playing youth ball, and he progressed through the American Legion leagues during his high-school years.

Virgil developed a reputation after high school as a strong-throwing infielder and outfielder. Playing for company teams including A.C.I., Hightower, and then Stockham Pipe in the Birmingham City League, Trucks caught the attention of scouts. Eddie Goostree, a roving scout for the Detroit Tigers, signed Trucks to a contract as an outfielder in 1937 and awarded him a $100 bonus.4

Because he had not been assigned to a team by May, Trucks decided to play semipro ball for Shawmut in the Chattahoochee Valley League, a textile league. Brunner Nix, a Shawmut catcher, thought Trucks would make a great pitcher because of his arm strength. “Nix more or less worked with my control,” Trucks said. “I could throw pretty hard, but was a little bit wild. He got me to the point that I got the ball more over the plate. He taught me about spinning the curveball.”

At the conclusion of Shawmut’s season, Andalusia of the Class D Alabama-Florida League called: “They came and asked me if I would play for them in the [league championship] series,” Trucks remembered. “They’d pay me $35 a game and expenses. I pitched and won the opening game, 3-0; I pitched another game and won 5-0. They wanted me to sign a contract with them. They said they’d give me $700. And I just let that fly by because I had already signed a contract with the Detroit Tigers.” But ultimately he signed with Andalusia and was now under contract with them and the Tigers.

Back home in Birmingham during the offseason, Trucks wasn’t sure what to do or which contract was valid. “I started to get contracts from Beaumont, Texas, which was the Detroit farm club,” he said. “And then I got one from Andalusia. I’d just send them back, saying it was not enough money. I thought they’d come and arrest me for taking their money.” So he decided to ignore the problem altogether and contacted Fob James, manager of the Lanett, Alabama, team in the same semipro league where he had played in 1937. In an exhibition game against the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association, Trucks met manager Paul Richards, who later played a pivotal role in his career. “Paul wanted to sign me also,” Trucks said, but his conscience bothered him and his pitching suffered. “I finally confessed to James what I had done. I said that I don’t know who I belong to and I keep getting contracts. … I went to see him [later] and he said that you are the property of Andalusia. I asked how that could be since I signed with Detroit first. He said that Detroit pigeon-holed the contract.” “Pigeon-holing” was a practice of not submitting contracts to major-league baseball.

Trucks earned his national reputation as a strikeout artist while pitching for the Andalusia Bulldogs in 1938. Jack House, sportswriter for the Birmingham News, saw him pitch and gave him the apt moniker “Fire,” which stayed with Trucks his entire life. The Sporting News ran front-page headlines about his pitching exploits and his new record for most strikeouts in a season in Organized Baseball with 420, breaking Hoss Radbourn’s record set in 1884.5 (Later research has established that Matt Kilroy struck out 513 for Baltimore of the American Association in 1886.) Trucks was 25-6, pitched two no-hitters, had a 1.25 ERA, and wound up in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not comic strip.6 Yam Yaryan, manager and part-time catcher of the Andalusia Bulldogs, suggested that Trucks alter his birth date to appear two years younger. Throughout his playing career, 1919 was given as his year of birth.

After seeing Trucks pitch for Andalusia, Eddie Goostree helped secure the sale of his player rights to Detroit. Trucks reported to the Tigers’ Beaumont Exporters, a team in the Class A-1 Texas League, in 1939, but due to his inconsistent pitching he was demoted to Class D, the Alexandria Aces of the Evangeline League. He had the opportunity to pitch regularly, regained his confidence, and finished with a 13-5 record. Trucks reported back to Beaumont to start the 1940 season and pitched consistently, though not spectacularly, for manager Al Vincent, including his third no-hitter. His 12-11 record earned him a trial at the Tigers’ spring training in 1941.7

Trucks reported to the Tigers in Lakeland, Florida, with a rebellious reputation due to his attitude and clashes with Vincent, which resulted in disciplinary actions and fines on several occasions. At the end of spring training he was optioned to the Buffalo Bisons of the Double-A International League, managed by the recently promoted Vincent. They reconciled their differences, prompting Trucks to comment, “I was just a thrower until Vincent’s coaching began to set in.”8 His 12 wins and league-leading 204 strikeouts earned him a September call-up.

On September 27, 1941, Trucks made his major-league debut in the top of the fifth inning with the Tigers down 8-4 at home against the Chicago White Sox. “I learned something and it taught me a lesson that I remembered for the rest of my career,” he said. “I had a guy steal home on me from third base.” With no one out and a player on third, Trucks was stunned when the player broke for home. “The first time I looked,” Trucks said, “he was almost at the plate. I wanted to hurry up my throw, but that would have been a balk. He’d have been safe anyway. He stole home without a tag! With him on third base, I took my windup. I should have glanced at him, but I didn’t.” And that was the last time someone stole home with Trucks on the mound. Just over two months later, Pearl Harbor was bombed and Trucks wondered what would happen to his baseball career.

In 1942 Trucks arrived at spring training anticipating being in the starting rotation. He made his first career start in the fourth game of the season, losing 7-6 to the Browns in St. Louis. In his second start, on his birthday, he notched his first career win, but afterward lost his place in the rotation due to wildness. After being idle for a month Trucks had another poor start, on May 22, and manager Del Baker considered demoting him. Pitching for his future, Trucks tossed a complete-game four-hit victory and followed it with his first career shutout, a six-hit gem against the Athletics at Philadelphia to cement not just his spot on the team, but also in the rotation. By September The Sporting News considered him the best hurler on the staff.9 He finished his rookie season with a team-high 14 wins and a 2.74 ERA.

Because of wartime travel restrictions, the Tigers conducted spring training in Evansville, Indiana in 1943, and new manager Steve O’Neill had big aspirations. However, the Tigers duplicated their fifth-place finish from the year before. In establishing himself as a big-league starter, Trucks put up even better numbers in his second full season, including 16 wins.

Trucks’ will to succeed and ability to navigate through unwritten rules of baseball etiquette helped ease his transition to the major leagues. The Tigers had an older staff in 1941 and “rookie pitchers were teased and aggravated,” he said. Furthermore, Trucks was a Southerner with an accent. “Some of the players didn’t like Southern ballplayers,” he recalled, “and they stayed away from us.”

At the end of the 1943 season Trucks took his military physical and decided to enlist in the Navy with the hope of being assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, outside Chicago, and playing Navy baseball for coach Mickey Cochrane.10 “I never got to play for Mickey when he was at Detroit and I always admired him,” Trucks recounted in an interview. The 1944 Great Lakes Bluejackets were a powerhouse, winning 48 of 50 games against major-league, minor-league, college, and industrial-league teams. With a starting lineup comprising major leaguers, including Billy Herman, Gene Woodling, and Schoolboy Rowe, and superior minor leaguers, they had a reputation as a “17th major league team.”11 Typically two or three games were played each week at the base in front of 10,000 to 12,000 sailors, which provided a major-league atmosphere.12 The Bluejackets played 14 of the 16 major-league teams, beating all except the Brooklyn Dodgers. Trucks pitched 48 innings against major-league teams, gave up just 21 hits and five earned runs, and won all four of his decisions; cumulatively, he was 10-0 with 161 strikeouts in 113 innings.

The Navy’s Admiral Chester Nimitz challenged the Army to a Military Service World Series in Hawaii. Both rosters comprised major-league stars, but the Navy squad, managed by Bill Dickey, may have been the most talented service team ever assembled; it included Phil Rizzuto, Johnny Mize, Dom DiMaggio, Pee Wee Reese, Johnny Vander Meer, and Virgil Trucks.13 In front of 20,000 servicemen at Furlong Field in Honolulu, Trucks threw a four-hit shutout in game one.14 The Army and Navy decided to play all seven games regardless of the outcome and the Navy proceeded to win the first six and lose game seven when Trucks gave up a home run to Ferris Fain in the last inning.15 Trucks was on active duty in 1944 and 1945 in Hawaii and several islands in the South Pacific, where he played baseball against local military base teams.

In the summer of 1945 Trucks aggravated his already injured knee on Guam, and was ultimately discharged. “There was a minor-league catcher at the rehab center. He and I got together and I’d throw to him every day and run a bit. That’s all the training I had for the World Series.”

Trucks was discharged near the end of the baseball season. He met the Tigers in St. Louis to play the final two games. A win against the Browns would give the Tigers the pennant. And in dramatic fashion, Trucks was chosen to start the first game. “I had just gotten out of the service three days before I joined the ballclub,” Trucks said. “Paul Richards was one of the coaches and catchers on the ballclub. He warmed me up a little and said that I was available to pitch if the Tigers wanted to use me.” After a rainout, his start was pushed to Sunday. Trucks pitched three-hit ball for 5? innings, giving up just one run. Hank Greenberg’s grand slam with two outs in the ninth won the game and propelled the Tigers to the World Series.

Owing to an exemption that allowed returning servicemen to join their teams at any point in the season and sill be eligible for the World Series, Trucks was on the roster.16 The Tigers, led by a pitching staff that outfielder Hub Walker called TNT (Trout, Newhouser, and Trucks),17 were set to play the Chicago Cubs. In the first game, in Detroit, the Tigers and AL MVP Newhouser were pummeled, 9-0, which seemed to affirm the team’s collective nickname as “nine old men.”18

Trucks started the pivotal Game Two and pitched the most important game of his life: a complete-game 4-1 victory. “That was the greatest thrill I think I’ve had in baseball,” he said. Cubs manager Charlie Grimm said, “Virgil Trucks was faster than anyone we saw all year in the National League.”19 The Tigers went on to win the World Series in seven games. Sportswriter Frederick G. Lieb maintained that Detroit won because “Trucks tipped [the] pitching scale at the last minute.”20

The Tigers finished a distant second to the Red Sox in 1946 and Yankees in 1947, and a disappointing fifth in 1948 while Trucks struggled to find his prewar form. He won 14, 10, and 14; however, his ERA rose dramatically, his control suffered, he gave up an uncharacteristic number of home runs, and at times lost his spot in the starting rotation. At the conclusion of the 1947 season, the Tigers dangled him unsuccessfully in several trade attempts and manager Steve O’Neill expressed his disappointment in Trucks’ pitching: “He hasn’t measured up to specifications in the postwar era.”21 Trucks admitted, “I had a miserable season.”22 Back problems limited his motion, and his weight, which he fought with his entire career, rose to 220, about 20 pounds over his typical playing weight. One critic commented, “Trucks’ chief pitching flaw is that he throws everything with the same tempo and at the same height.”23

At 32 Trucks got off to the best start of his career in 1949, which helped end the trade rumors. He won his first four starts, including three complete games. He exhibited better control and location of his pitches and developed a good changeup. Importantly, he was pitching late into games, underscoring his improved conditioning. In a span of five starts in late May and early June, Trucks pitched four complete games, including three extra-inning games, and then followed those with two consecutive shutouts. Trucks attributed his transformation into one of the major leagues’ foremost winners to “an entirely new attitude,” support from new manager Red Rolfe, who took him off the trading block, and help from pitching coach Ted Lyons.24 “Ted Lyons,” Trucks recalled, “helped me to learn how to throw different pitches. He helped me mostly to improve my slider and curveball, and how to grip the ball. The slider is gripped entirely differently than any other pitch. It’s pitched with half of the ball outside of your hand and fingers.” Trucks finished the season at 19-11 with a 2.81 ERA and led the league in shutouts with six and strikeouts with 153. One of the season’s highlights was his first All-Star Game, which he won by pitching the second and third innings.

With high expectations, Trucks started 1950 where he left off the previous year. After his sixth start, an 11-inning shutout on May 13, he felt pain in his right arm for the first time in his life. Concerned and confused, he shrugged it off and made his next scheduled start, but didn’t survive the third inning. After diathermy treatment didn’t help,25 he was sent to Dr. Robert F. Hyland in St. Louis. “He gave me ten days of X-ray treatment,” Trucks said. “One beep each day on my upper arm, which was a pulled tendon. He told me when I left after ten days, if I try to throw and it hurts, then quit for the year. I went back and tried to throw. It hurt so, I didn’t throw. It probably saved my career by listening to him.” Trucks missed the rest of the season.

Based on his performance in 1950, Trucks’ 1951 salary was slashed by 25 percent and reported to be $15,000.26 After Trucks failed to show his usual velocity in the spring, manager Rolfe proceeded cautiously with his comeback. Rolfe relegated Trucks to the bullpen, where he struggled. On May 27 he won his first start of the year; it was his first win in 12½ months. He entered the starting rotation in mid-July and came on strong at the end of the season, recording complete games in five of his last six starts, including a 14-inning marathon. Manager Rolfe said, “He’s a better pitcher now than when he won 19 games … [has] better control and a curve. He can set up his hitters better.”27

Trucks’ 1952 season is one of the most incongruous and surprising ones imaginable. The Tigers suffered through the worst season in franchise history and Trucks had a 5-19 record. Deeper research reveals that not all those losses were his fault; the Tigers scored 0, 1, or 2 runs in 15 of his starts. Among his five wins were two no-hitters, a one-hitter, a two-hitter through 7? innings, and a six-hitter. After his first no-hitter, Trucks remarked, “Before my arm trouble, I depended mostly on my fastball. Now I am using curves and sliders … but my fastball has [also] returned.”28

In December Trucks was traded to the St. Louis Browns. “I thought [the trade] was awful,” he said. “I would have loved to stay with Detroit my entire career.” In 1953 he arrived in San Bernardino, California, at the Browns’ spring-training facility in “better shape than he has been in five years”29 and looking “like the old Trucks.”30 Manager Marty Marion was upbeat about the Browns, who had finished last or second-to-last in six of the previous seven seasons, and praised Trucks: “I’m counting on Trucks as the Browns’ number-one stopper.”31 He was tabbed the Opening Day starter against his former team. In overpowering fashion, the 36-year-old Trucks threw a four-hit shutout.

After two months Trucks was the Browns’ most effective pitcher, but they were in last place. Owner Bill Veeck, in financial difficulty, was fighting with the commissioner and the other owners, who had blocked his attempt to relocate his franchise. After being offered to several teams, Trucks was sent to the Chicago White Sox in June, primarily in order to infuse the Browns with needed cash to meet operating expenses. “I was traded five times,” Trucks recounted, “and Veeck was the only man who ever came to me, called me into his office, and told me that I was traded. I think Bill Veeck was one of the greatest guys that ever owned a ballclub. He gave me the absolute truth. He said [the American League] will not let him move the ballclub; the owners wouldn’t approve of it. He’s got to meet the payroll, so he’s selling me and Bob Elliott to the White Sox for $100,000 [actually $75,000] and getting a couple of ballplayers in trades.” During his brief tenure with the Browns, Trucks had his first African American teammate, Satchel Paige, whom he saw pitch two decades earlier in Birmingham in Negro League games. Paige and Trucks formed a strong friendship that carried into their post-baseball days.

The White Sox, Indians, and Yankees were in an exciting three-team battle for the AL pennant. The acquisition of Trucks paid instant dividends. After a no-decision in his first start, Trucks won his next eight starts. The Sporting News called him the “AL’s most effective pitcher”32 and teammate Minnie Miñoso called him “sensational.”33 Though the White Sox finished in third place, Trucks and Billy Pierce proved to be one of baseball’s best 1-2 punches. Trucks won 15 games for the White Sox, which gave him a season total of 20, his career high. At 36, he was among the league leaders in almost every major pitching category.

Trucks started 1954 where he left off the previous year, winning 10 of his first 13 starts. As a 37-year old, he relied less on his fastball and credited his success to a more mature approach. Trucks also revealed that he learned a new pitch: “Paul Richards [the White Sox manager] taught me his ‘slip pitch,’ which I used as a changeup.”34 He was named to his second All-Star Game, pitched a hitless and scoreless ninth inning (earning a save), and helped the American League defeat the National League, 11-9, in front of almost 70,000 spectators at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. With a record of 17 wins and just five defeats in mid-August, Trucks appeared to be headed for 20 wins again, but a series of nagging injuries and his teammates’ untimely hitting affected his performance. Trucks closed out the season 2-7. Again, he was among the league leaders in every major statistical category. After the season, Trucks signed a contract reported at $35,000 and exclaimed that it was the “highest salary I ever received.”35

After a slow start in 1955, Trucks was reportedly in general manager Frank Lane’s doghouse for not performing up to expectations36 and new manager Marty Marion’s for his lack of focus. “He [Marion] didn’t pitch me like he should have in 1955,” Trucks said. “He’d skip me … and I didn’t like that. He wasn’t my kind of manager.” Trucks’ and Marion’s antagonism traced back to their time together on the Browns. An outspoken critic of Marion, Trucks resented that his manager demanded that the 45-year-old Satchel Paige take part in all of the running and training exercises scheduled for pitchers. Now, as a 38-year-old, Trucks was obviously slowing down, but his competitive spirit was not. He was not ready to back down from any challenge in the clubhouse or on the field. In response to claims that he used the brushback pitch too much, Trucks replied, “I believe it is necessary and legitimate [when batters are] crowding the plate.”37 He finished with a 13-8 record.

After expressing his desire to pitch, but not as both a starter and a reliever (“I’m too old for that.”38), Trucks was traded back to the Tigers for Bubba Phillips in December 1955. Manager Bucky Harris hoped to squeeze what he could out of the former Tiger star: “We realize Trucks has quite a few years on him, but all we want is one more good season.”39 The oldest player on the roster, Trucks had developed a knuckleball while barnstorming in previous years and honed it in spring training,40 but a series of injuries limited his effectiveness. He made just 16 starts and won only six games. It was clear that Trucks had lost his velocity and that his days as a starter were over. In December 1956 the Tigers traded him in an eight-player deal to the Kansas City Athletics. It was his fourth trade and fifth team in five years.

With his typical optimism, Trucks arrived at spring training with the A’s claiming, “The club is 50 percent better than it was last year and the pitching staff is 100 percent improved.”41 Privately, however, he told friends and family that this would be his last season. After getting pummeled in spring training, Trucks was assigned to the bullpen, where he pitched in a career-high 48 games and won nine to lead the team.

Lured back to the A’s in 1958, Trucks pitched well, with an ERA hovering near 2.00 after 16 appearances. His effectiveness caught the eyes of the Yankees, who had attempted to acquire him the previous season to shore up their bullpen. They traded for him in June and Trucks went on to pitch in 25 games for the Bronx Bombers. Though “totally surprised” by the trade, Trucks could not replicate the same success he had with the A’s. He was hit hard in a few initial outings before finding a groove in late July and August. After a couple of poor outings in September, he apparently lost manager Casey Stengel’s confidence. The Yankees won the pennant, but Trucks was left off the World Series roster. Trucks had a poor relationship with Stengel and commented, “I disliked him in every sense.” Trucks was persuaded to serve as the batting-practice pitcher for the Yankees in the World Series, which they won in thrilling fashion, over the Milwaukee Braves in seven games.

Approaching his 42nd birthday, Trucks held out to begin the 1959 season, and ultimately signed in March after taking a 25 percent pay cut, the maximum allowed.42 Out of shape and still disappointed at being left off the World Series roster, he struggled in spring training and was released in April. Trucks said, “I just lost the desire to play even though I felt fine. There was nothing wrong with me physically. My arm was all right. I just couldn’t get myself motivated to play.” Bill Durney, general manager of the Miami Marlins in the International League, persuaded Trucks to attempt a comeback and offered him a $5,000 bonus no matter how he pitched.43 After a few uninspired performances, Trucks ended his professional playing career.

In an 18-year major-league career during which he lost practically two full seasons to military service, Trucks won 177 games and lost 135, recorded 33 shutouts, and compiled a 3.39 ERA. He won another 65 games in the minor leagues. Though it is impossible to know how Trucks would have pitched in 1944 and 1945, or if he would have been injured, it is not far-fetched to assume that he would have won another 30 to 38 games based on his performance before and after his military service. Had that been the case, he would have finished with career numbers similar to those of his peers and Hall of Famers Hal Newhouser and Bob Lemon. Trucks was considered one of the hardest throwers in major-league history. (Ted Williams thought Trucks was the fastest pitcher he ever faced, and supposedly an Army radar gun clocked him at 105 miles per hour.)44 Trucks was also remarkably resilient and suffered just one debilitating arm injury. Commenting on his delivery, Trucks said, “I was primarily an overhand pitcher. I never dropped down to side-arm. That was a reason I lasted so long. Because of throwing overhand, I could follow through; your arm follows through to where you are not putting a lot of pressure on it.”

Throughout his playing career, Trucks held a variety of jobs and had a number of business interests to augment his income and support his family. He directed youth programs, worked for railways and shipyards, operated baseball camps, owned a beer distributorship, and even served in the emergency police reserve in Detroit as a volunteer in case of a nuclear attack on the city.45 But the most lucrative opportunity for extra income during the offseason was barnstorming.46

Trucks’ return to the major leagues in 1960 was the result of a botched barnstorming tour showcasing him and Satchel Paige. “Paige had a barnstorming tour all set up. Just he and I were going to be the ones who pitched on the tour. We had a busload of young ballplayers from Cuba. We opened the season out in Kansas and went south until we got to Mexico.” Unfortunately, Trucks and Paige were not paid as promised, Paige quit, and the Castro revolution in Cuba forced the players to return home.

In 1960 Trucks hooked on with the Pirates as a batting-practice pitcher, and stayed with the team until 1963. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, he had jobs in and outside of baseball. He operated baseball camps for Pirates, scouted Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania for the Seattle Pilots, served as a pitching coach for his former team, the Triple-A Buffalo Bisons, in 1971, and also served as a roving scout for the Braves and Tigers from 1970 through 1974. In 1974 he retired from baseball and returned to Alabama, where he spent most of his time.

At the age of 95, Trucks died in 2013 in Calera, Alabama, south of Birmingham, and was buried in the Alabama National Cemetery in Montevallo. He was survived by his fourth wife, Anne, whom he married in 2003. He had five children from previous marriages, Jimmie, Carolyn, Virgil, Darryl, and Wendy, as well as grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Looking back on his career and accomplishments, Trucks was insightful. “I would do it all over again,” he responded when asked about his military service. He had no second thoughts about losing almost two years of his prime. Always known for his humor, he continued, “Why wasn’t I traded to [the Yankees] in 1941? Because I’d definitely be in the Hall of Fame if I had been traded to [them].”

A version of this biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 The author interviewed Virgil Trucks on September 19, 2011. All quotations from Trucks are from the author’s interview with him unless otherwise noted.

2 All season and career statistics have been verified with http://baseball-reference.com. All games statistics have been verified with http://retrosheet.org/.

3 Virgil Trucks’ autobiography is an insightful and thorough book about his life and times. See Virgil O. Trucks, with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, Throwing Heat: The Life and Times of Virgil Fire Trucks (Dunkirk, Maryland: Pepperpot, 2004).

4 Trucks, 11-12.

5 The Sporting News, August 25, 1938, 1, and September 1, 1938, 1.

6 See Trucks, 27 for a reprint of the Ripley strip.

7 The Sporting News, September 12, 1940, 5.

8 The Sporting News, July 10, 1940, 5.

9 The Sporting News, September 3, 1942, 3.

10 Trucks, 77.

11 Trucks, 79.

12 The Sporting News, July 6, 1944, 17.

13 Trucks provides the starting lineup for both squads in his autobiography, page 81.

14 The Sporting News, September 28, 1944, 12.

15 Trucks, 82.

16 The Sporting News, October 4, 1945, 4.

17 The Sporting News, October 11, 1945, 7.

18 Fredrick G. Lieb, The Detroit Tigers (New York: Putnam, 1946), 263.

19 The Sporting News, October 11, 1945, 4

20 The Sporting News, October 18, 1945, 2. For an excellent history of the Tigers team in 1945, see Burge Carmon Smith’s The 1945 Detroit Tigers: Nine Old Men and One Left Arm Win t All (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co.), 2010.

21 The Sporting News, November 11, 1947, 9.

22 The Sporting News, December 24, 1947, 10.

23 The Sporting News, May 5, 1948, 11.

24 The Sporting News, June 29, 1949, 9.

25 The Sporting News, July 12, 1950, 20.

26 The Sporting News, January, 31, 1951, 8.

27 The Sporting News, October 3, 1951, 15.

28 The Sporting News, May 28, 1952, 13.

29 The Sporting News, February 25, 1953, 29.

30 The Sporting News, April 1, 1953, 22.

31 The Sporting News, April 22, 1953, 8.

32 The Sporting News, August 5, 1953, 4.

33 Minnie Miñoso and Herb Fagen, Just Call Me Minnie: My Six Decades in Baseball (Urbana, Illinois: Sagamore, 1994), 89.

34 The Sporting News, November 24, 1954, 21.

35 Ibid.

36 The Sporting News, May 11, 1955, 18.

37 The Sporting News, September 28, 1955, 14.

38 The Sporting News, November 30, 1955, 36.

39 The Sporting News, December 7, 1955, 6.

40 The Sporting News, April 11, 1956, 7.

41 The Sporting News, March 20, 1957, 27.

42 The Sporting News, February 25, 1959, 6.

43 Trucks, 248-9.

44 Doug Segrest,”5 Questions: Former major leaguer Virgil Trucks,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, December 18, 2009. http://blog.al.com/birmingham-news-sports/2009/12/5_questions_former_major_leagu.html

45 The Sporting News, December 20, 1951, 15.

46 Arguably the most definitive book about barnstorming is Thomas Barthel’s Baseball Barnstorming and Exhibition Games 1901-1962. A History of Off-Season Major League Play (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007). Barthel provides a comprehensive list of barnstorming teams and rosters.

Full Name

Virgil Oliver Trucks

Born

April 26, 1917 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

March 23, 2013 at Calera, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.