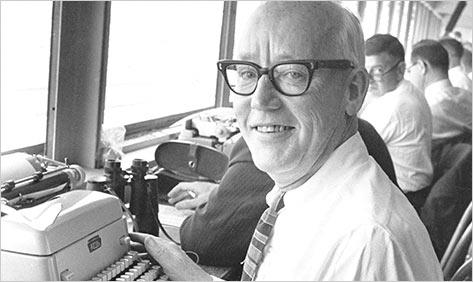

Walter “Red” Smith

Red Smith, a small, shy man with a commonplace name, was an uncommonly stylish writer. Amid the purple bombast of the sports pages, “he was the first who gave us a license to really write English,” a colleague, Jerry Izenberg, said.1

Red Smith, a small, shy man with a commonplace name, was an uncommonly stylish writer. Amid the purple bombast of the sports pages, “he was the first who gave us a license to really write English,” a colleague, Jerry Izenberg, said.1

“He was not just a great sports writer,” fellow Pulitzer Prize winner Dave Anderson wrote, “he was a great American writer in the class of Hemingway and William Faulkner.”2 Ernest Hemingway called him “the most important force in American sportswriting.”3

“I flinch whenever I see the word literature used in the same sentence with my name,” Smith wrote. “I’m just a bum trying to make a living running a typewriter.”4

Besides a Pulitzer Prize, he won the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s J.G. Taylor Spink Award; George Polk Award; Grantland Rice Memorial Award; and was the first recipient of the Associated Press Sports Editors’ Red Smith Award for lifetime contributions.

For years he wrote 800 to 900 words a day, six days a week. “There’s nothing to writing,” he said. “All you have to do is sit down at the typewriter and open a vein.”5 When a young writer asked him how to do a sports column, Smith told him, “Be there.”6 He believed in shoe-leather reporting, not armchair pontificating. “It was people he was most interested in,” his biographer, Ira Berkow, wrote. “Games came second.”7

No twirlers, twin killings, or circuit clouts marred Smith’s columns. Leaving behind the overwrought clichés of the genre, he wrote plain and graceful English decorated with humor wherever he could find it. He thought sports was entertainment, and he strove to entertain.

A Red Smith sampler:

- Ninety feet between bases is the nearest to perfection that man has ever achieved. It accurately measures the cunning, speed and finesse of the base stealer against the velocity of the thrown ball.8

- Rooting for the Yankees is like rooting for U.S. Steel.9

- Of a losing football team: They had overwhelmed one opponent, underwhelmed twelve, and whelmed one.10

- A writer he didn’t like was dedicated to the ruthless stamping out of the simple declarative sentence.11

- A spectacular defensive play by Jackie Robinson was the unconquerable doing the impossible.12

- Baseball is dull only to dull minds. Today’s game is always different from yesterday’s game, and tomorrow refreshingly different from today.13

Smith was born in Green Bay, Wisconsin, on September 25, 1905, the second of three children of Walter Philip Smith and the former Ida Richardson. Ida claimed to be a descendant of the Duke of Wellington, whose given name was Arthur Wellesley, so she named her sons Arthur and Walter Wellesley. (Smith later learned that the duke had no legitimate direct descendants.) His father owned a wholesale and retail grocery business with two brothers. The boy was called Wells, then Brick, and finally Red, for his hair.

Wells was short, slight, and wore glasses. He played baseball, poorly, but his favorite participatory sport was trout fishing, a passion he would carry for life. When he graduated from high school, he told his father he planned to be a newspaperman. “Whoever heard of a newspaperman with money?” the senior Smith asked. His son replied, “Who ever heard of a Smith with money?”14

He had to work for a year to save money before entering Notre Dame, where he waited tables and served as secretary to a professor from his hometown. He joined the track team, coached by football coach Knute Rockne, but quit after he finished last in his first mile race.

After graduation Smith found his first newspaper job with the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1928, making $24 a week as a general-assignment reporter. A year later he moved to the St. Louis Star as a copy editor, with a raise to $40. When half the sports staff was fired for taking payoffs to promote wrestling matches, he was transferred to the sports department — an accidental sportswriter — and covered the Cardinals and Browns. He met Kay Cody at a party and married her in 1933.

In 1936 the Philadelphia Record offered him $60 to cover the Athletics and write a seven-day-a-week column. “Red Smith” was born in Philadelphia when he told an editor to change his byline from Walt Smith.

By the end of World War II Smith was approaching 40 and supporting his wife, daughter, Kit, and son, Terry, on $80 a week, plus earnings from freelance magazine articles, when he made the big time. Stanley Woodward, sports editor of the New York Herald Tribune, had scouted the “little guy on the Philadelphia Record” by having his secretary clip a month’s worth of Smith’s columns. When they met, Woodward told him, “You are the best newspaper writer in the country and I can’t understand why you are stuck in Philadelphia.”15

The Herald Tribune’s circulation trailed its morning competition, the Daily News and Times, but Woodward was determined to make his sports section Number One. A hulking former college football tackle who was called “Coach,” he recruited the best writers and cultivated them with gruff love. He advised Smith to “stop godding up those ballplayers.”16

Smith started with the Trib as a general-assignment sports reporter for $100 a week. On December 5, 1945, he began the six-day-a-week column that would be an ornament for the paper for the rest of its life. Woodward told him, “Keep the column entertaining and write anything you want short of libel.”17 Within a few years the column was syndicated to newspapers nationwide. With Smith’s share of syndication revenue, Woodward commented that he was “making telephone numbers” — five figures, not beginning with a 1.18

The shy Midwesterner became a star on the New York sports scene, a regular at Toots Shor’s saloon, which he called “the mother lodge.”19 He soon qualified for Shor’s Table #1. His best friends were other sportswriters: Frank Graham, Grantland Rice, and Shirley Povich, three of the most distinguished practitioners of the craft. They traveled together to the biggest stories on the baseball, college football, boxing, and thoroughbred racing circuits while consuming lakes of liquor — scotch or sometimes vodka and tonic, no lime, for Smith.

Baseball was his favorite sport, outdistancing boxing and horse racing by a nose. He had no use for basketball and warned against hockey and other winter sports that would “freeze your toes off.”20

Unlike many other luminaries in his trade — including Damon Runyon, James Reston, and Jimmy Breslin — Smith rejected most opportunities beyond the sports page. He covered the presidential nominating conventions in 1956 and 1968, writing about them as if they were sporting contests, but otherwise stuck to his corner of the world. He turned away offers to write books; all of his books were compilations of columns. His colleague Dave Anderson wrote, “If being a sportswriter was good enough for Red Smith, it had to be good enough for anybody”21

At its peak, his column was carried by more than 250 papers, and his work was studied in university writing classes. By 1958 Newsweek magazine put him on its cover as “the world’s most widely read sportswriter.”22 The next year he and Kay were guests on Edward R. Murrow’s popular CBS-TV show, Person to Person.

But the 1956 Pulitzer Prize, journalism’s Oscar, went to Arthur Daley of the New York Times, the first sportswriter to be honored for commentary. (There is no Pulitzer for sportswriting.) Smith, and many of his colleagues, were stunned. He sometimes made fun of Daley’s plodding prose, which seldom if ever revealed an original thought. “It made Red angry,” Povich recalled, “and he pointed out that they gave Daley the Pulitzer Prize for General Excellence of his columns. Red said, ‘Name one.’”23

Just as Smith was at the top of his game, three newspaper strikes in the 1960s killed the Herald Tribune and three other New York dailies. Their remnants rose from the dead in a new paper, the World Journal Tribune, but that horse designed by committee lasted only eight months. The surviving papers — the Times, Daily News, and Post — had a full stable of sports columnists, so Smith was left with no New York outlet. He continued his column in syndication, and Women’s Wear Daily improbably picked it up, making him the New York garment industry’s most widely read sportswriter.

As he faced uncertainty about his career, Smith’s wife was diagnosed with liver cancer. He nursed Kay through the next four months while continuing to write his column. For a change, writing was a relief. Kay died on February 15, 1967.

With the loss of his wife, his paper, and most of his New York audience, Smith appeared to be in decline as he neared retirement age. He began drinking heavily, alarming friends and his son, Terry, a New York Times reporter. Smith’s older brother, Art, also a newspaperman, was an alcoholic who had failed in several tries at sobriety.

After 34 years of marriage and a year of widowhood, Smith hesitantly began dating Phyllis Weiss, a widow 15 years younger with five children in their teens and early 20s. She may have saved his life; she and her kids certainly changed his outlook. They were married on November 2, 1968.

His career also rebounded. In 1971 the New York Times, the world’s most influential newspaper, had an opening for a sports columnist. Managing editor A.M. Rosenthal said he asked himself who was the best of the breed, and had no doubt about the answer. The 66-year-old Smith called his hiring “reverse nepotism,” since his son already worked for the Times. Years later Rosenthal said, “I get depressed sometimes editing this paper. But whenever I get down, I say to myself, ‘Wait a minute. I hired Red Smith.’”24

Smith shared the “Sports of The Times” column with Arthur Daley, each writing three a week, with Dave Anderson contributing two. After Daley died in 1974, Smith and Anderson each wrote four.

The Times nominated Smith for the 1976 Pulitzer Prize without telling him. He was the second sportswriter, after Daley, to be honored for excellence in commentary. Publicly Smith was suitably grateful, but he confided to his friend Tom Callahan that the prize meant nothing to him: “It’s part of being with the New York Times.”25

Smith’s peers honored him that same year with the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Spink Award for sportswriters. “Smith had a fine sense of the absurd in human conduct and a penetrating perception of detail for accuracy,” the Hall said.26

Now in his 70s, Smith was an old man following young men’s games. He began writing more about the games off the field, the social issues behind the scenes of athletic competition. He acknowledged that he had missed the broader significance of Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color line. He had written often about Robinson the player, but seldom about his symbolic importance. In the 1960s, when Muhammad Ali refused to serve in the army on religious grounds, Smith lumped the heavyweight champion with the “unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war.”27

His columns for the Times reflected a more liberal outlook. He thought his stepchildren had helped open his mind to new ideas. He railed against the Olympic movement’s devotion to phony amateurism and the NCAA’s profiteering off the unpaid labor of student athletes.

He had long opposed baseball’s reserve clause, and his coverage of the Players Association was “so different from other writers of his era, such as Dick Young,” said the union leader, Marvin Miller. “When he asked a question, I felt certain it was because he wanted to know the answer and that he would not ignore the facts that didn’t fit a preconceived opinion.”28 Smith blamed the owners for the strike that wiped out much of the 1981 season.

He had also ridiculed the women’s rights movement. When a student sports editor, Anne Morrissy, became the first woman accredited to the Yale Bowl press box in 1954, Smith called her a “crusading cupcake.”29 He thought a press box or locker room was no place for a woman. But in the 1970s he mentored Jane Leavy early in her career writing sports for newspapers and magazines. Once, finding Leavy shut out of the Yankees’ clubhouse because of her gender, the Pulitzer winner gave the cub five pages of notes and quotes.30

Smith’s writing about issues raised a stink when he called for a U.S. boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He wrote two columns on the subject, but only one appeared in the Times. Sports editor Le Anne Schreiber objected to the second column because it contained an important factual error and was peppered with what she considered excessive Cold War rhetoric. On deadline, she couldn’t reach Smith — he had taken his wife to the theater — so she killed his column.31

When word leaked out, Smith’s fellow columnists hammered the Times for censorship. He pronounced the kerfuffle “a bloody bore.”32 He said he disagreed with the decision, but the paper had a right to reject the column.

Smith’s health began to deteriorate in the late 1970s. He underwent surgery for bladder cancer and again for colon cancer. Congestive heart failure left him short of breath. He found it increasingly difficult to “be there,” and usually wrote in a barn behind his country home in Connecticut.

The Times offered to reduce his workload, and his son pleaded with him to slow down. He finally agreed to cut back. After turning in his first column on the new three-a-week schedule, he went into a hospital and died at 76 on January 15, 1982.

“Dying is no big deal,” Smith said once. “The least of us will manage that. Living is the trick.”33

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Notes

1 Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism, http://povichcenter.org/still-no-cheering-press-box/chapter/Jerry-Izenberg/index.html, accessed December 9, 2016.

2 Povich Center, http://povichcenter.org/still-no-cheering-press-box/chapter/Dave-Anderson/index.html, accessed December 9, 2016.

3 “1976 J.G. Taylor Spink Award Winner Red Smith,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. http://baseballhall.org/discover/awards/j-g-taylor-spink/red-smith, accessed January 8, 2017.

4 Ira Berkow, Red Smith: The Life and Times of a Great American Writer (New York: Times Books, 1986), xi.

5 Ibid., 208.

6 David Halberstam, “His Greatest Hits,” New York Times, July 2, 2000: BR7.

7 Berkow, xi.

8 Red Smith, Red Smith on Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), x.

9 Berkow, 15.

10 Ibid., 16.

11 Ibid., 270.

12 Smith on Baseball, xi.

13 Ibid., x.

14 Berkow, 18.

15 Stanley Woodward, Paper Tiger (repr. Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison, 2007), 231.

16 Jerome Holtzman, No Cheering in the Press Box ((New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973), 259.

17 Berkow, 98.

18 Woodward, 232.

19 Smith, Strawberries in the Wintertime (New York: Quadrangle, 1974), 300.

20 Shirley Povich, “Red Smith: The Death of a Friend, the Loss of an Artist,” Washington Post, January 16, 1982: G3.

21 Dave Anderson, “Living Is the Trick, But Without the Lime, Thank You,” New York Times, January 17, 1982: S3.

22 Berkow, 149.

23 Ibid., 143.

24 Ibid., 248.

25 Ibid., 228.

26 “1976 J.G. Taylor Spink Award Winner Red Smith.”

27 Berkow, 186.

28 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game (New York: Birch Lane, 1991), 57.

29 Sam Roberts, “Anne Morrissy Merick, a Pioneer from Yale to Vietnam, Dies at 83,” New York Times, May 10, 2017: B15.

30 Jane Leavy, “Farewell to the Uncommon Man,” Washington Post, January 17, 1982: M4.

31 Berkow, 250-253.

32 George Solomon, “Red Smith, Sportswriter, Pulitzer Honoree, Dies,” Washington Post, January 16, 1982.

33 Anderson.

Full Name

Walter Wellesley Smith

Born

September 25, 1905 at Green Bay, WI (US)

Died

January 15, 1982 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.